Читать книгу An Unlikely Countess: Lily Budge and the 13th Earl of Galloway - Ziauddin Yousafzai, Louise Carpenter - Страница 10

3 Virescit vulnere virtus: Valour grows strong from a wound

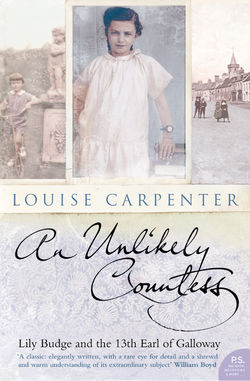

ОглавлениеOn 14 October 1928 at 2.45 a.m., in a large, elegant bedroom on an upper floor of 34 Bryanston Square, London W1, the 12th Countess of Galloway, gave birth to a son and heir. The boy was christened Randolph Keith Reginald Stewart, names chosen in honour of his father, grandfather, and uncle. There was also the courtesy title of Lord Garlies, which the child would keep until his father’s death, whereupon he would succeed to the title of 13th Earl of Galloway. When Randolph arrived into the world that morning there was no indication of the troubles that lay ahead. Physically, he was perfect. Lord Galloway, the 12th Earl, could rest easy. Three years before Lady Galloway had delivered a daughter, Lady Antonia Marian Amy Isabel Stewart. Now that there was a boy the line would live on, for another generation at least.

Lord Galloway was an accomplished historian, particularly when it came to how the Earls of Galloway, one of Scotland’s oldest noble families, fitted into Britain’s history. They remain one of the main lowland branches of the Stewarts, and, in the absence of a chief, are considered by the Stewart Society, founded in Edinburgh in 1899 to collect and preserve the history and tradition of the name, to be senior representatives of the clan. If a lineage dating back to the twelfth century seemed irrelevant to a small boy born after the First World War, then it was not considered to be so by that boy’s father. Documents and articles held in the Stewart Society library bear many of Lord Galloway’s annotations and corrections. His heritage brought him great pride. He did not care for family members who chose to forget it.

The Galloway earldom has its roots in the Lord High Stewards of Scotland, whose line also produced the Stuart monarchs. When David I gave the 1st High Steward, Walter, his position, he effectively made him Scotland’s equivalent of Chancellor of the Exchequer and occasional army general. It was the third High Steward – also called Walter – who turned the title into his family name, which continues to this day. An unbroken male line descends from Sir John Stewart of Bonkyl, who died at the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Two of his sons fought alongside Robert the Bruce and were rewarded with lands. Their cousin, Sir Walter, later the 6th High Steward, also distinguished himself as a commander at Bannockburn in 1314. He was knighted on the battle field by Robert the Bruce and later married his daughter. Fifty years on, their son became King Robert II. In 1607 James I made Sir Alexander Stewart Lord Garlies. Sixteen years later he created for him the Galloway earldom. Queen Elizabeth II is a direct descendant of the royal Stewarts through the female line.

The early bravery and military inclinations of the Stewart relatives – some destined to become the Earls of Galloway – continued through the centuries, right up until Randolph’s birth. Some stood out. Lieutenant General Sir William Stewart, fourth son of the 7th Earl and Countess of Galloway, for example, co-founded the Rifle Brigade and fought in the Napoleonic Wars. His journals and papers, known as the Cumloden Papers and dating from 1794 to 1809, preserved at the family seat of Cumloden, contain a record of his achievements and include revealing correspondence from the Duke of Wellington and Lord Nelson.

Everything Lord Galloway knew and felt to be true about life derived from his family legacy. He was born on 21 November 1892, to Amy Mary Pauline, the only daughter of Anthony John Cliffe of Bellevue, County Wexford, and christened Randolph Algernon Ronald Stewart. His father, Randolph Henry Stewart, son of Randolph, 9th Earl of Galloway, had joined the 42nd Highlanders in 1855 straight from Harrow School. In his military career he survived some of the empire’s most significant conflicts. He served in the Crimea and was present at the siege and fall of Sebastopol (for which he received a medal with clasp and the Turkish war medal) and also at the Indian Mutiny, during which he was present at the fall of Lucknow (another medal with clasp). He retired, as a captain, in 1876. He was fifty-five by the time he married, fifty-six when his first son was born, and succeeded as 11th Earl of Galloway, following the death of his elder brother, the 10th Earl in 1901.

Two harrowing events in early adulthood had shaped Lord Galloway’s life. The first was the death of his younger brother, the Hon. Keith Stewart, killed during the First World War, and the second was his own experience serving in the Scots Guards during the first battle of Ypres. Wounded and close to death, he had been captured by the Germans and kept prisoner before finally being returned home.

Even before the Lieutenant Hon. Keith Stewart’s death on 9 May 1915, when he was head of the leading platoon of his regiment, the Black Watch, in the charge on Aubers Ridge, near Festhubert in Flanders, he was regarded by all – family, friends, schoolmasters – as extraordinarily brilliant, a rather special boy who, had it not been for his brother’s status as first son and heir, might well have eclipsed him in every way. At Harrow he was head of school, captain of the football First XI, had won the public schools’ fencing competition in 1911, the Macnamara Prize for English three years running, and had passed second into Sandhurst in 1913, then fifth out a year later. He was gazetted to the Black Watch in August 1914, and went to the front in the December. (Lord Galloway – then ‘Garlies’ – had been at Harrow School only a year when his brother arrived and his own time there would prove to be not nearly so distinguished.)

It was inevitable that the tragic, early death of such a young man would shock the family. Keith Stewart epitomised all they stood for: brains, honour, courage, strength, and patriotism. It was some while before his body was recovered, but his popularity was so great that both commissioned and non-commissioned officers went looking for it at considerable risk to their lives. His corpse was eventually found lying within a few yards of the German trenches. It was brought back and buried by the British chaplain in the cemetery of Vieille Chapelle. In the months that followed the news his father received many tributes. Tommy Graham, who fought with him, sent back to Britain wounded, wrote to him:

He was young as far as his years are concerned, but he was old in wisdom … He never asked one of us to do something which he would not do himself: he shared our hardships and our joys; he was, in fact, one of ourselves as far as comradeship and brotherly love was concerned … We never knew who he was till we saw his death in the Press; but this we did know, that he was Lieut. Stewart, a soldier and a gentleman every inch … it’s not every day one like Stewart joins the army. There was not a man in his platoon, or the regiment for that part, but would have willingly went through hell for him, and mind you we faced hell out there on more than one occasion.’

Graham had heard of the death from another officer, Lance-Corporal Alexander ‘Sandy’ Easson, who broke the news thus:

We have lost little Lieut. Stewart … the best man that ever toed the line … None of the rest of them ever mixed themselves with us the same as he done. He was a credit to the regiment and to the father and mother who reared him; and Tommy, the boys that are left of the platoon hope that you will write to his father and mother and let them know how his men loved him … He died at the head of his platoon like the toff he was, and Tommy, I never was very religious: but I think little Stewart is in heaven. We knew it was a forlorn hope before we were half way – but he never flinched.

The Galloway family motto is Virescit vulnere virtus – valour grows strong from a wound – and so it proved for Lord Galloway, who adhered to it throughout his life. As soon as he had recovered, both from injury and from the loss of his brother, he became honorary attaché to the British legation in Berne in 1918, and then, after the war, in 1919, ADC to the military governor of Cologne. A year later his father died and he succeeded to the title. That he would incorporate his brother’s name into that of his son and heir shows how the legacy of Keith lived on. The military tradition into which the two brothers had been born sets in context the assumptions and expectations Lord Galloway would come to make of his own son, just as, one imagines, they had been made of him. It also explains the enormous sense of disappointment, bewilderment, and shame he would come to feel when he found that his heir could not live up to them. For now, though, Lord Galloway had no reason to suspect that when he married his beautiful young bride, their genes would mix so badly.

Lord Galloway’s marriage to Philippa Wendell in 1924 was seen by society as a second splendid match for the Wendell family, descendants of the victorious American Civil War general, Robert E. Lee. The Wendell sisters were not just beauties – Catherine, the eldest, was blonde and graceful, and Philippa, ‘a vivacious brunette’ – they were American beauties, bringing with them the wealth that the British aristocracy so badly needed. In the fifth volume of The Stewarts: A Historical and General Magazine for the Stewart Society, the tribute to their union reads: ‘To none of all the alliances formed in recent years between fair Americaines and members of the British aristocracy does so much interest attach – historically and genealogically at least – as to that just celebrated by Miss Philippa Wendell and the Earl of Galloway.’ Two years earlier, in 1922, Catherine had married the Earl of Carnarvon. That Philippa had followed her into the aristocracy by marrying a Scottish earl, one whose ancestry placed him at the head of the Stewart clan, was considered another piece of good fortune. ‘She comes on both sides of the house from some of the very oldest New England families,’ the report in The Stewarts gushed, ‘and, it may be added, of pronounced Royalist sympathies.’

The new Lady Galloway was perfect in every way. She was a beauty with fine, noble features. She had pale skin and dark, thick hair (Randolph was to inherit her colouring), cut into a bob and worn pulled back from her face, showing off to good effect the sharp angles of her cheekbones and jawline. She enjoyed listening to and playing classical music, which particularly delighted the musical dowager countess, who in the past had held her own festivals at Cumloden, and she wrote plays and poetry (the latter published in Punch). Added to this her uncle by marriage, Mr Percival Griffiths, possessed a fine and extensive private collection of Stewart relics. There were wonderfully wrought royal layette baskets, miniatures of Charles I hand-worked in silk; a lock of the ‘Royal Martyr’s hair’; the hawking outfit – pouch, lure, and gloves – of James VI and I; the Bible of Charles II in its bag of Royal Stewart tartan velvet – ‘probably the oldest example of that tartan in existence’ – along with rings, medallions, and trinkets.

Shortly after their marriage Lord and Lady Galloway took a house in London which led the Daily Telegraph to speculate that ‘Lady Galloway would blossom out as a leading London hostess’. She did not. Lord Galloway found that he preferred being on his estate, for which he now felt a great responsibility. Although Lady Galloway had chosen to have her baby in London, soon after Randolph’s birth they travelled back to Scotland.

Cumloden is situated in the county of Kirkcudbrightshire in the south-west, close to the towns of Newton Stewart and Minnigaff. It was not a stately home, but a converted hunting lodge, orginally built in 1821 by Sir William Stewart. The family’s main seat had been the grand and imposing Galloway House, also in the south west, but that had been sold off in 1908 due to the family’s dwindling funds. Cumloden was a low white house with black timbers, not remotely grand or imposing. At the front, there was a porch with a verandah, framed by trees, rhododendrons, laurels, box hedges and azaleas. Inside, to the right of the entrance hall, a couple of steps led off to the billiards room and the main telephone room.

Along the south-west front of the house were Lady Galloway’s sitting room; Lord Galloway’s study; a bedroom called the Orange Room for important family guests; a little store room; and the drawing room, off of which was an ante-room leading to a conservatory always filled with flowers. Double doors led from the drawing room into the dining room, outside which was a hall leading to the bedroom of the head housemaid, and underneath was the wine cellar. A flight of stairs led off to the north wing where Lord and Lady Galloway had adjoining bedrooms (Lady Galloway’s room had a spectacular view). The dowager countess also slept in a pretty room in the north wing, despite it being considered the coldest room in the house. Across the passage was a bathroom and a set of box rooms where Lord and Lady Galloway stored their much-used travel bags. From here another flight of stairs led up to the bedrooms used by the gaggle of old Stewart aunts and American relatives whenever they visited. These rooms also ran along the south-west front of the house and were called South Room (with appropriately facing dressing room), Balcony Room, Blue Room, and Roof Room. The layout continued in this manner – a series of rambling wings connected by a rabbit warren of corridors and narrow staircases. The focal point of it all, close to the entrance hall, was the grand and central spiral staircase.

The beauty of the estate, however, lay not in the house, however comfortable the interior, but in the lands, which stretched beyond the eye could see and included a deer park that Randolph would grow to love. To the west was Kirkland, the nearest farm, and further beyond, up the Wood O’Cree Road, looking over the River Cree, sat All Saints’, Challoch, the family’s church and burial yard.

On inheriting all this Lord Galloway grew further into his new role and began applying himself to a myriad of public duties. He became justice of the peace for Kirkcudbrightshire and in 1932, four years after Randolph’s birth, he was appointed Lord Lieutenant of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright. This role lasted until 1975 and involved lunches with Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, from whom – in terms of old-school austerity and iron backbone – he was not dissimilar. The same year as Lord Galloway began representing the Queen, he also embraced masonic life. He was initiated into Lodge St Ninian, No. 499, and became Right Worshipful Master when he took office in Grand Lodge as Junior Grand Deacon. (In 1945, he would become Grand Master Mason.)

Unsurprisingly Lord Galloway’s responsibilities and his extensive travelling dictated the rhythm of the household. Randolph’s early years were typical of a post-war childhood in a big house, at one turn privileged, at another, by today’s standards, emotionally lacking. It would have been quite unthinkable by the standards of his class for Lord Galloway to make his many trips abroad without his wife. As a result Randolph spent much of his time with a succession of nannies, nurses, and governesses. The year was divided into time spent at Cumloden; a large house in Sandridgebury, near St Albans, where Lady Galloway had grown up following her father’s death – a fine residence with butlers and footmen, chauffeurs for the two Rolls-Royces, cooks, general maids, and scullery maids; and London. The London trip occurred in late January, usually when Lord and Lady Galloway were abroad, and the children would travel up with the nannies to stay at 39 Lowndes Street, where they would remain until just before Easter. The children adored these trips. In the cold London air the nannies would walk them round Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, where they would stand, eyes wide with delight, before Peter Pan’s statue. Occasionally they would go to Bryanston Square, where Randolph had been born, and curl up with Nana, their mother’s old nurse.

Just before Easter the children would be brought back to Cumloden where they would remain until July. The nursery toy box overflowed. There were puppets, clockwork cows, and the ‘bunny express’, an engine in lapine form that sounded a bell as it chuffed around the track. There was a toy cinema, countless picture books, and annuals – a favourite being the series of adventures of the Peek-A-Boos. Lady Antonia had a large and intricate doll’s house, which in fine weather was moved into the play hut in the grounds of the house, and Randolph had three sets of trains with tracks, two containing green engines with chocolate and cream coloured coaches with multi-coloured roofs. The puppet theatre was a favourite. If Lord and Lady Galloway were in residence, the countess would make sure all adults attended performances, including the sombre dowager. Often Lady Galloway would go behind the puppet stand herself. There were picnics in the surrounding beauty spots, which brought the children much joy, but not always the adults, particularly the dowager. The sun annoyed her, any wind drove her frantic, and in the rain she would sit alone in the Rolls complaining of her misery and wishing she was by the drawing room fire.

Come July the children would transfer to Sandridgebury where they would stay until October. During these months Cumloden would be let out to rich holidaymakers and Lord and Lady Galloway would travel to Europe or beyond, announcing their departure in the broadsheets. The trip south was a complicated operation involving much luggage. At 8.30 a.m. on the dot Mr McGowan would arrive in the Rolls ready to drive the nannies and their charges to Dumfries station, the starting point of their long journey south. The nannies would then shepherd the children into the car while Mr McGowan struggled with the numerous trunks, hat boxes, Gladstone bags, books tied with string, attaché cases, and luncheon boxes, as well as the portable wireless and gramophone. At Sandridgebury they would be met by another Rolls, driven by Hubert French, and in the back seat sat a delighted Mrs Percival Griffiths. Mr Griffiths was equally pleased by their presence in his large house, and often liked to take them to Whipsnade Zoo in the Rolls, although he would get cross if they made a noise during his afternoon nap.

All things considered, with old great aunts pressing upon him as many Fuller’s peppermints as they could manage, Randolph thought himself happy at Sandridgebury. It was one long blissful summer of hide and seek, sardines, netball, rounders, tennis, croquet, and golf. And in October, on his birthday, there would always be a party during which his great aunt would stamp about the hall, much to the children’s delight, shouting ‘Do you know the Muffin Man, the Muffin Man, the Muffin Man? Do you know the Muffin Man who lives in Drury Lane?’

And so this was the cycle of Randolph’s early life, spent largely in the bosom of extended family and in the care of familiar, loyal servants who were always on hand to ensure the smooth running of the houses. Cumloden had a large staff, most of whom lived on the estate with their families, so that as Randolph’s anxieties began to take hold, and he became prone to wandering the grounds alone, these familiar, weather-beaten faces seemed part of his world even though they came from a quite different one. Mr Curry, for instance, who tended the grounds, tidied the woodland paths, cut the wood, and ensured the house remained heated, lived with his wife in a cottage in the deer park. Mr Malcolm Scott, the head gamekeeper, lived with his wife and daughter, Monica, at Cumloden Lodge, which sat at the south entrance (Monica was responsible for opening the gatehouse gate and waving in the Rolls). It was often the case that the house employed several members of the same family. The succession of cooks – Mrs Robertson, Mrs Cockie, Mrs Partridge, Mrs Bain, Mrs Clark, and Mrs McNabb – and the roll call of butlers – Mr Leashman, Mr Campbell, Mr Hopkins, Mr Sparks, and Mr Wright – tended to arrive alone, but the coachman’s daughter, for example, was head housemaid and parlourmaid. Randolph’s favourite servant beyond all others, the one he continues to talk of in adulthood, was Nan Dalrymple, the laundry maid and wife of the station hand at Newton Stewart railway station. Often he would seek her out in the laundry room and she would embrace him with vigour – an unfamiliar but very pleasant sensation.

Randolph and Lady Antonia were initially educated at home. They were woken at 7 a.m. by the school-room maid with a glass of hot water ‘that tasted awful’, as Randolph remembered later, and in the afternoon, after lessons, they rested for an hour before being taken for a walk around the grounds by their governess. There was rarely a shortage of company though. Children of family friends were always being invited over for parties and on Tuesdays in spring, after their return to Cumloden, the portable gramophone and a box full of records, including selections of Irish and Scottish country dances, would be carried down from the school-room and set up in the billiard room where Miss Border, the dancing instructress, would hold classes for them and their friends. But Randolph’s fear of his father slowly began to overshadow all. His ‘personality problems’ began early, long before he left Cumloden for Belhaven Hill, one of the most fashionable Scottish preparatory schools at that time. He cried when he left Cumloden for Sandridgebury and he cried when he left Sandridgebury for Cumloden. He was often making a scene, ‘either public or private or both’, he recalls. This irritated and angered Lord Galloway, who expected his son to behave with dignity, composure, and formality. It did not help that Randolph was a slight, sickly child. Whenever he contracted a cold or the flu, the school-room was turned into a sick bay.

Years later, when he was an adult, Randolph wrote of a puppet show that his mother had performed for him during his childhood. She named it ‘The Child in the Bath’, and in tone it chimes rather tragically with the feelings Lord and Lady Galloway would come to have regarding their own son. In the show the mother puppet placed her infant child in the bath and left the stage. While she was gone, ‘the Black Witch, an evil woman’ entered and snatched the baby. ‘No happy endings,’ wrote Randolph, ‘for both parents were so upset, they had no idea of the visitation of such a demonic and odious prowling spirit.’

For all the joyful innocence of the nursery, the picnics and the toys and the parties, Cumloden remained a formal household. Lord Galloway believed in the same values as his own father and his approach to child rearing was rigid and unbending. It was not an atmosphere suited to an increasingly odd and eccentric little boy. In 1935, for example, Randolph threw a tantrum at the news that a newly appointed governess would shortly be arriving in the schoolroom. Poor Miss Daisy Cook, who appeared armed with milk of magnesia and syrup of figs. ‘Tears of wretched despair … and dejected despondency adorned my face in the schoolroom, when writing Christmas letters of thanks,’ Randolph recorded. ‘Miss Daisy Cook was not amused by my attitude.’

Randolph was not a good student and when he did badly, he would sob or scream, which would have Miss Cook shouting back at him to bring himself under control. Other staff began to notice his oddities. On one occasion, following a telling off by the dowager countess, he displayed more peculiarity, fussing about and breaking wind (a habit that he never thought to control). ‘I was swiftly removed by Mother to the schoolroom,’ he wrote, ‘wherein I became aggressive and threatened Winnifred [school-room servant] on her approach.’ Mr Leashman, the butler, witnessed the incident and was ‘deeply shocked’. But Randolph did not apologise for his behaviour. He broke wind again, which had the effect of ‘bringing a dark frown to the butler’s face’.

Randolph’s eccentric behaviour was not confined to Cumloden. Reports would often drift back from outings with other children, and events would often occur at house parties that confirmed he was unlike the other boys. During one house party in June 1934, the housekeeper took the children to the coast of North Berwick (not far from where Lily lived). Randolph ran away and everybody got soaked in the rain while they looked for him. During one stay at Sandridgebury, the children were taken to a private tea party by their aunt. Randolph had promised to behave, but once there he found it impossible to rise to the challenge. He muddled up the names of all the guests – understandable in an eight-year-old child – but then went on to insult the host, Mr Parr, by telling him that his study smelt of rats and tobacco. ‘It may smell of tobacco, Garlies,’ said the surprised Mr Parr, ‘but it does not smell of rats!’ To which Randolph had rudely retorted, ‘Yes, it smells of tobacco and rats, and is the smelliest house I have ever been in!’ Throughout the rest of the tea, Randolph continued to break wind, which had his aunt slowly dying of shame. Back at Sandridgebury she told him that never in her life had she been so mortified. ‘Signorita’, who helped with the children when they stayed, told him wisely, ‘If you do this at school, teacher will come and put you in the lavatory!’

These minor acts of bad behaviour only make sense in retrospect. At the time the puzzled Lord and Lady Galloway consoled themselves that their son would change with age. What he needed was to grow and toughen up. What he needed was the discipline of prep school. There he was sure to metamorphosise from cry-baby into a proper boy possessed of a dignity befitting his title, and a spirit strong enough for the future challenges of Harrow School. In the summer of 1937, before Randolph was due to start at Belhaven Hill School in Dunbar, the headmaster, Mr Brian Simms, came to Cumloden for lunch. Randolph was petrified and thought him horrid. He did not like the way he ‘fixed [him] with a cold and hard eye across the dining table’.

That September Randolph left Sandridgebury with his mother and father. They were met at St Pancras station by the dowager countess and together they travelled to King’s Cross in order to catch the train back to Scotland. Randolph’s behaviour during the journey was not encouraging. When a locomotive blew its steam, he began screaming. Lady Galloway became angry and told him to stop being so babyish. Once on board the train his behaviour changed completely and he became jolly, babbling a list of nonsensical words that his mother sweetly wrote down on some notepaper for him. They spent the night of the twenty-eighth in the North British Hotel in Edinburgh (to become the Balmoral). Randolph was ‘as potty as ever, making the craziest of noises’, and smelling and blowing his sweet wrappers. The following day they travelled to Dunbar where Lord and Lady Galloway delivered Randolph to Belhaven for the beginning of Michaelmas Term. As they disappeared down the drive, he stood watching them from the front porch. For the first time in his life, he was alone, about to begin a new phase of his life under ‘the iron rule of Mr Brian Sims [sic]’.