Читать книгу The Gay Detective - Lou Rand - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction: Mystery as History

ОглавлениеSusan Stryker and Martin Meeker

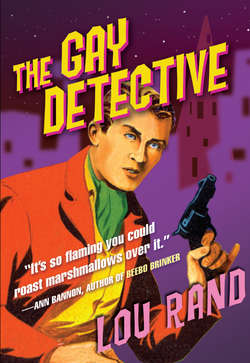

Lou Rand’s The Gay Detective is a genre-busting gem of a story written in the waning days of the golden age of American “pulp” paperback publishing. Until now it has been largely forgotten by readers and disparaged by the few critics who ever took notice of it, but we think you’ll agree as you peruse the following pages that the book deserves a wider contemporary audience.

The Gay Detective can best be described as “hard-boiled camp.” The plot revolves around a grisly murder/blackmail/narcotics racket, but the cast of characters includes a gracefully aging chorus boy who packs a pistol and carries a private investigator’s license, a down-on-his luck football stud who might not be as shocked as one might expect upon learning that some boys do more than bathe in a bathhouse, and a vivacious vixen with a taste for rough trade and a roomful of kinky secrets. Along the way we meet handsome thugs, catty drag queens, sleazy businessmen, corrupt cops, tainted politicians, and a gossip columnist who bears more than a passing resemblance to the late, great San Francisco Chronicle newspaper columnist Herb Caen.

The Gay Detective is set in “Bay City,” a thinly disguised San Francisco. The action takes place in the late 1950s and early 1960s, just as that fabled city was earning its reputation as a world-renowned gay gathering-spot. While this tightly plotted little book offers a fun time for readers who don’t know a thing about San Francisco’s queer past, to those in the know, The Gay Detective also provides a fascinating guide to a place known since the mid-19th century as “Sodom By the Sea.” It’s a history, as well as a mystery—and it’s written by a man almost as mysterious, and just as historically noteworthy, as the characters he created.

San Francisco isn’t the only thing about The Gay Detective that’s thinly disguised. “Lou Rand” supplies only slight cover for chef and writer Lou Rand Hogan, who under the name Lou Hogan penned regular items for Sunset and Gourmet magazines. The historical record reveals little about the man, but the few anecdotes and pieces of evidence that have survived are all intriguing. He was born in Los Angeles at the turn of the last century and moved to San Francisco as a young man in the 1920s. Those two California cities would remain his principal ports-of-call over the next several decades, but his career as a chef took him to exotic locales around the globe. Hogan worked as a chef aboard the Matson luxury liner Lurline on its regular San Francisco to Honolulu to Sydney run, he served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and ruled the roost in such exclusive Bay Area dining rooms as those of the Bohemian Club, the Palace Hotel, and the Mark Hopkins. At other times he worked as a personal chef for billionaire industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and for the Sultan of Jahore in Singapore.

While dishing up Continental cuisine for the rich and famous, Hogan also took time to dish in print about two central features of his life: food and the gay world. He achieved his widest public with his Gourmet and Sunset gigs, but later in life he also contributed to The Advocate, San Francisco’s Bay Area Reporter, and other gay publications. Hogan’s twin passions intertwined most famously—and notoriously—in The Gay Cookbook. This “compendium of campy cuisine,” published in 1965 by Sherbourne Press in Los Angeles, gained a cult following and went through numerous printings. The cookbook’s readers were treated to serious haute cuisine recipes as well as generous servings of vintage ’60s humor—an unrelenting cascade of double entendre that played on the apparently endless parallels between the kitchen and the bedroom. Hogan’s introduction for “Browned Beef Stew” clearly demands a parenthetical reference to “browning” and “frenching.” The book’s decidedly male (and often overtly misogynistic) bias is made clear by the disclaimer that it contains no recipes for fish.

Hogan’s adventurous life ended with little fanfare in Los Angeles in 1976. He left no known heirs, no will, no correspondence or personal papers. Apart from his essays and books, the man left few traces of his private life. Based on a brief, unpublished essay written by Hogan, we know that he considered the pseudonymous Robert Scully’s early gay novel The Scarlet Pansy (1932), which chronicled the party-filled life of a beautiful boy named Fay in the years around World War I, to be the most accurate representation of the kind of life Hogan himself had led. Moreover, Hogan wrote that The Scarlet Pansy was a “noteworthy book” because “it marked the beginning of a world-wide social trend”—gay literature. He admired the book so much that he hoped his short essay would be the introduction to a reissue of the work, but these plans never came to fruition.

Most of what we do know about Hogan is derived from a short series of reminiscences he published as “The Golden Age of Queens” in 1974 in the Bay Area Reporter, under the nom de plume Toto Le Grand. Hogan’s persistent use of pseudonyms might appear odd to out-and-proud gay readers today, but he acted as did most gay men of his generation, prizing privacy and anonymity over the double-edged sword of notoriety. Those reminiscences offer intriguing insights into the real-life underpinnings of The Gay Detective, written against a backdrop of sweeping historical change in the city of San Francisco, in the organization of “old gay life,” and in the relationships between sexuality, vice, and crime at a time when homosexuality was itself illegal. In them, we see much of Hogan’s character and personal style, and are treated to a few juicy anecdotes that paint a telling picture of the society in which he moved. Hogan made it clear that during the Roaring Twenties the most raucous gay life appeared on the street. “Looking back,” he wrote, “it must be repeated that Market Street was the focal point of all the action; remember, up until 1932, there were no bars open as such, you ‘met’ on the street. Every foot of it, from the Anchor Bar at the Embarcadero corner to the Crystal Palace Market, could tell a story, all interesting.” Along with engaging in the “promenade” up and down the street “to show off new ‘outfits’, hair-do’s, jewels, and the like,” Hogan wrote about one of the “interesting” stories that unfolded in the Unique Theater, formerly located on Market Street between Third and Fourth. Originally opened as a grand movie palace during the Silent Era, by the late 1920s “this old grind house,” according to Hogan, had fallen into disrepair and it was a place one might find a “middle-of-the-night trick.” Hogan added that because “the house was kept so dark (to hide its grime) one could DO the trick right in his seat, if one were agile enough. This was quite often managed!”

The celebratory, sex-affirming tone so evident in “The Golden Age of the Queens” did not secure a lasting literary reputation for Lou Rand Hogan. He has gone entirely unmentioned in queer-focused encyclopedias, “who’s who” lists, and other reference works. The Gay Detective similarly has been overlooked in the numerous anthologies of gay literature and historical overviews of gay fiction that have now been produced. The Gay Detective was initially published in 1961 by Saber Press of Fresno, California, and the history of that publishing house helps explain some of the obscurity that has surrounded The Gay Detective since its initial appearance. Saber Press was owned and operated by Sanford Aday, allegedly a former pimp, and his partner Wallace de Ortega Maxey, an ordained minister and early member of the pioneering gay rights group the Mattachine Society. Most Saber Press books—with titles like I Peddle Jazz, Camera Bait, and Our Flesh Was Cheap—dealt with lurid, semi-sleazy topics. They had low production values and limited distribution, but they were quite tame compared to the graphic pornography that would begin to appear before the end of the 1960s. Saber’s proprietors repeatedly ran afoul of the law in that more censorious era; after selling a copy of Sex Life of a Cop through their mail order business to a customer in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Aday and Maxey were convicted of shipping lewd materials through the mails. They were fined $10,000 and sentenced to several years in prison.

Although lesbian works of various quality and veracity abounded (and sold well) in the “golden age” of paperback publishing between World War II and the rise of the sexual liberation movement in the mid-1960s, print representations of gay male life were harder to come by and faced greater barriers to distribution. In a culture where straight men might take voyeuristic pleasure in fantasizing about lesbian sexual scenes (and thus provide a wide non-lesbian audience for lesbian-themed paperbacks), books with gay male themes were targeted primarily at a gay male audience, and were much more vulnerable to homophobic legal attacks. Consequently, even paperback works that had some substance, like The Gay Detective, were relegated to publishing houses that survived in the margins of respectability. To a certain extent, the taint of disreputability has always clung to Hogan’s novel, both in its initial release by Saber and its subsequent republication under the title Rough Trade (with a slightly revised text), by Argyle Books in 1964.

When post-gay-liberation literary scholars have taken note of The Gay Detective at all, one senses a trace of embarrassment in their dismissive tone. Roger Austen, in his seminal 1977 book, Playing the Game: The Homosexual Novel in America, says that Hogan’s novel was nothing more than “tepid.” James Levine’s 1991 survey, The Homosexual Novel in America, takes an even more critical tack. Levine writes, “Lou Rand’s Gay Detective is an inferior mystery novel with some feeble attempt at humor…. Throughout most of the novel, gays emerge as stereotypically effeminate queens. The story of a gay detective who solves the crimes committed by those preying on gay men sounds positive, but this is not the case. The few masculine gay men are the murder victims. The police chief, who is aware of the crime syndicate, and his friend who ran it both escape prosecution…. In short, the blackmailing of gay men is shown as only mildly reprehensible and popular stereotypes of gay men were not disputed.”

Levine’s concern with effeminate stereotypes lies at the heart of Hogan’s negligible critical reputation. Hogan himself identified as an effeminate “queen,” and he wrote his book in the then contemporary “queen’s vernacular” of a now-vanished gay male world. Hogan’s milieu was organized along butch/queen lines that resembled in some respects the better-known butch/femme gender system of the lesbian world. He was consequently neglected by a generation (or two) of gay editors whose political sensibilities were forged in reaction to that older gay way of life, and who were more comfortable with newer styles of gay masculinity that disparaged effeminacy.

In fairness to Hogan’s critics, charges of effeminacy have been historically important ways of oppressing gay men; it is equally true that some critiques of effeminacy harbor a masculinist bias against the feminine. We as contemporary readers have an opportunity to step outside the ideologically motivated frameworks of previous decades, however, to reappraise older literary works in their historical context—indeed, the glimpses we catch of social realities that no longer exist provide much of the pleasure of such texts. The Gay Detective is admittedly light fare, perhaps tepid in its lack of sexual explicitness and stereotypical in its representations of gay male gender conventions, but to dismiss the book’s worthiness on those grounds reveals more about the assumptions and agendas of contemporary critics than they do about the ultimate value of Hogan’s detective story.

And in the end—whatever one thinks about the dated language, corny humor, unfortunate anglocentric prejudices, or politically incorrect representations of gender and sexuality—Hogan’s novel is primarily a detective story. On this level the book succeeds wonderfully, and readers will just have to find out for themselves whodunit and why. Rather than spoiling the plot, however, we want to act as tour guides to the San Francisco on which Hogan patterned his fictional Bay City, alerting readers to the local color and sites of historical interest they’ll encounter when following the main characters on Hogan’s fabulously fruity tour of a seedy sexual underground.

Mystery writing and historical studies might seem at first glance to be worlds apart: mysteries are generally fiction and histories are ostensibly fact; mystery authors write to delight and confound the reader while historians write to educate and explain; mystery novels generally end with all loose threads being tied up, while histories generally wind up posing more questions than they can answer. There are similarities, too, of course. Investigation, hypothesis, and evidence are important features of both genres, as the writer constructs a narrative designed to gradually reveal some version of truth. And as is often the case in sleuthing of either sort, some of the most revealing evidence is found not through conscious acts of seeking, but rather in stumbling upon something unexpected.

This is precisely how The Gay Detective came to our attention. While working on their 1996 book Gay by the Bay, a history of queer culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, Susan Stryker and her co-author Jim Van Buskirk skimmed through the San Francisco Public Library’s vast, recently-acquired collection of lesbian and gay paperbacks, assembled by lesbian publisher Barbara Grier of Naiad Press, looking for San Francisco–related materials. The Gay Detective was one such find. Neither Stryker nor Van Buskirk spent much time at that point digging into the novel’s historical background, and contented themselves with reproducing the cover art for a pictorial spread in Gay by the Bay.

A few years later Stryker shared the book with the San Francisco Queer History Working Group, whose other members included Martin Meeker, Willie Walker, Gayle Rubin, and Paul Gabriel. That’s when the historically grounded nature of the novel’s back story became visible, as nearly half a dozen historians pieced together what they knew about various aspects of San Francisco’s mid-century history based on their own original research. The group members quickly realized that while Hogan’s detective tale offered an enjoyable evening’s read, it also supplied something far more substantial: a veritable road-map to the inner dynamics of “pre-liberation” gay culture. That realization is what prompted us to seek republication of this neglected and forgotten work, with a new historical introduction.

Even in its most superficial details, The Gay Detective is so chock full of references to the contemporary culture of San Francisco that the book practically begs for historical analysis. The Backroom Crowd at Flanagan’s Bar, to whom we are introduced in the second chapter and whose centrality to the plot is revealed only towards the end of the book, are all modeled on prominent San Francisco figures. Jake Eberhart is based on headline-conscious society lawyer Jake Ehrlich, who had gained a name for himself defending the likes of Billie Holiday and notorious madam Sally Stanford—and for having his victories published in the book Never Plead Guilty. Senator Martin resembles real-life Senator (and former San Francisco Mayor) James K. Phelan who, like his fictional counterpart, was a “confirmed bachelor” hailing from the highest rungs of the social ladder. Joe Cannelli, a night club operator with a “live and let live” attitude towards the city’s burgeoning homosexual population, has more in common with Joe Finocchio—proprietor of the famous female impersonator venue Finocchio’s—than an Italian surname. Then there’s gossip-columnist Bert Kane, a fine caricature of three-dot journalist Herb Caen. In spite of his apparently vigorous heterosexuality, Caen’s generally good-natured columns displayed on occasion such intimate knowledge of his beloved city’s gay life that rumors persisted about his own sexual practices. As Hogan says of Caen’s fictional alter ego in The Gay Detective, “anyone knowing that much of the words and music is bound to have done the dance routines too.”

Like the supporting cast of characters, many of the story’s locales are drawn from the material world. Canneli’s Bait Room is not quite Finocchio’s, but it’s a reasonable facsimile of “Fin’s” chief competitor, the slightly more downmarket and risqué Beige Room, which was located on Broadway at the crossroads of North Beach, Chinatown, and Nob Hill. Likewise, the generically named Baths bathhouse, where the novel’s climactic action takes place, also had a brick and mortar prototype, Dave’s Baths, situated near the waterfront on the edge of North Beach. Hogan goes so far as to mention the controversial new Embarcadero Freeway (whose construction would soon be halted by the grass-roots “freeway revolt”) then being built adjacent to Dave’s. One of the book’s cleverest settings—a gym by day, an illicit after-hours club by night—actually existed in San Francisco’s then mostly black Fillmore neighborhood, but Hogan, the cheeky chef, fictionalized the Gourmet Club as the Gourmand Club.

More significant than the myriad parallels between characters and places are the situations that motivate the plot. Blackmail is at the heart of the story, and in this respect, too, Hogan draws on lived experience. The fear of exposure as a homosexual that led Hogan to mask his identity in much of his explicitly gay writing has been a persistent feature of gay life, one that was even more prevalent in earlier decades of the 20th century than it has been recently. In his autobiographical “The Golden Age of the Queens,” Hogan makes the shocking admission that he himself had stooped to blackmail in the dark days of the Great Depression—befriending straight military officers at tony Nob Hill hotel bars, stealing their wallets to learn their identities and addresses, and later demanding money in exchange for not spilling the beans to the men’s wives and commanders. Usually, however, the exploitation worked in the other direction, with countless gay and bisexual men ruining themselves financially to avoid the social stigma of public accusations of homosexuality.

Interestingly, given the historical veracity of much else in Hogan’s novel, there are tantalizing clues in another mid-century gay paperback about a blackmail ring in San Francisco. Bud Clifton’s otherwise forgettable Muscle Boy (Ace, 1958), also set in the Bay Area, details a scam quite similar in its particulars to the one uncovered by Hogan’s gay detective. In describing Muscle Boy in his 1964-65 Guild Book Service mail order catalog of gay-interest titles, pioneering anti-censorship activist H. Lynn Womack notes that “this thinly disguised fiction” allows readers familiar with the San Francisco scene to “enjoy identifying” the characters, “because they are from real life, as real as life around … California can be.”

Less apparent to the casual reader is the way in which the spatial organization of semi-public and commercial sexual activity in Hogan’s Bay City mimics what local historians have uncovered about the interrelationships between mid-century San Francisco’s gay neighborhoods and commercial sex and “vice” districts. Without giving away too many details of the plot, gay detective Francis Morley and his sidekick Tiger Olsen follow a trail of crime that begins in a high-profile night-spot patronized by “slumming” socialites, tourists, and open-minded “bohemians” as well as by gay men and lesbians. The action then moves to a more marginal after-hours joint before finally arriving at the steamy, seamy Baths.

In the process, the protagonists move from a tourist-oriented entertainment district, to an inner-city slum, to a derelict waterfront, all the while moving deeper and deeper into a criminalized underworld of illegal drugs and sexual variance. In doing so they map a circuit through which the city’s sexual appetites once circulated. What seems most fascinating here is the way in which Hogan’s story depends on the consequences of criminalizing all sorts of non-reproductive erotic activity and pleasure-seeking stimulation, as well as on the unexpected couplings of high society with low life that transpire in the shadowy back-ways of the city. Buried beneath all the fluff, Hogan’s book offers a serious political critique: he shows how social privilege is preserved by casting non-normative sexuality out into the margins of society, but also how the sexual margins are preserved precisely because they offer a space for the socially privileged to enact desires and practices condemned by an oppressive and hypocritical society. It was in this space, structured by the needs of elites, that pre-liberation gay life was allowed to flourish, and to be exploited.

Exploitation is the hinge upon which the sexual double standard turned. In true noir style, Hogan depicts a world whose very order depends upon outlaw spaces over which cops and criminals—two rival gangs—vie for the ability to profit from the people and activities relegated to the sexual margins. Even more impressively, however, the back story Hogan offers as motivating force for his foregrounded tale of blackmail and murder involves a sense of sweeping historical change. He shows how broad social developments that had nothing directly to do with homosexuality nevertheless worked to disrupt and reconfigure the underworld of vice and crime in ways that led to the emergence of new—and newly politicized—gay identities and communities.

In a pivotal scene in which gay private detective Francis Morley is called in to help the Bay City Police Department solve a string of murders involving gay men, we learn that the law has taken an interest in the murders primarily because there seems to be some connection between the murders and a new movement of narcotics into the city. An FBI agent assigned to the case, clearly uncomfortable with the gay angle that has emerged in the investigation, asks the local police officers why Bay City “has such an overlarge percentage of these queer people.” In response, Captain Morphy, head of the Bay City Vice Squad (who may be modeled on a notorious Sergeant Frank Murphy, much reviled by the gay community of San Francisco for his zeal in targeting homosexuals for arrest) offers a lengthy explanation that reveals much of Hogan’s historical vision:

Y’see, this town used to be wide open. It was the talk of the world, being a seaport and all. Things were pretty much under control, and everyone was making a little money. Then these people that always want to clean up everything—well, it seems that after they lost out on prohibition, they decided to run all the ‘hoors’ out of town. Finally, we had to close up all those quiet, friendly, well-regulated houses…. This put all the girls on the streets and hustling in bars, unregulated and uninspected, too. Even this didn’t satisfy the ‘do-gooders.’ First we had to run ’em off the streets, and now it’s outa the bars, too. I dunno. This is a sailor’s town. It was once a great port. I guess these young fellas today just gotta do something with the time on their hands.

Hogan’s implication that male homosexuality increased in San Francisco between the end of Prohibition and the early 1960s because of a lack of female prostitutes needs to be taken with a grain of salt, but his story of shifting relations between the police department and the sex industry is an accurate account of what happened in San Francisco in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. With the closure of the old Barbary Coast through the Red-Light Abatement Act in 1917, most prostitution in the city became concentrated in the downtown “Tenderloin,” which was under the tight control of the corrupt, bribe-and-kickback taking cops of the Central Station. Prostitution had been allowed to flourish in the Tenderloin since the 19th century, as long as the police got their share of the financial action. Street-walking was not allowed; the police would steer sex workers they encountered to one of the many houses of prostitution that offered police pay-offs in exchange for the privilege of doing business without interference. At one point in the early 20th century, the city of San Francisco had even tried to legalize prostitution, as long as sex workers remained in the Tenderloin and visited a municipal health clinic twice a week to test for sexually transmitted disease. The police force would have none of it, because legalization undermined their lucrative extortion racket, and they successfully brought pressure to bear on elected officials through a cynically manipulated morality crusade to have prostitution recriminalized. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, powerful constituencies whose ideas of civic virtue differed from those of a corrupt Central Station police force had begun to break down the well-established, self-interested “regulation” of inner-city prostitution.

Contesting police control of the Tenderloin “vice trade” was related to changes in the physical fabric of San Francisco and the wider Bay Area. In the years after World War II, which saw a dramatic increase in the region’s population, a sweeping regional master plan was put in place that, over the ensuing quarter century, gradually transformed San Francisco’s downtown into a financial nexus for the Pacific Rim, moved much of the city’s heavy industry and port facilities across the bay to Oakland, encouraged a large-scale migration to the suburbs through cheap home loans, and interconnected the entire region with a new system of freeways and mass transit (BART—the Bay Area Rapid Transit system). The social and economic dislocations wrought by these spatial changes—like the withering away of San Francisco’s maritime trade mentioned by Captain Morphy—dramatically changed the “sexual ecology” of inner-city San Francisco. The police struggled to retain a grip on their traditional turf, but they were swimming against the tide of the times.

Hogan connects the emergence of a newly visible gay community at this moment in time with the broader social shifts he noted. When the federal agent asks Morphy what his discourse on prostitution has to do with “all these open ‘fag’ bars and joints,” Morphy replies:

Personally, I always want to plant a foot in those cuties’ butts, but the new Commission has psychiatrists now who advise that these people should be allowed to congregate in their own places. I suppose it does eliminate a lot of friction—fights and stuff that might get started in regular joints. Yeah, and it does make it easier for us in a sense, ’cause we can keep an eye on them better.

A visible gay community, Hogan implies, resulted in part from the loss of traditional opportunities for corrupt police vice regulation. Significantly, at the very time Hogan was writing, San Francisco newspapers carried stories of the so-called “Gayola” scandal, in which owners of gay bars, emboldened by a recent California Supreme Court decision protecting the rights of homosexuals to congregate in public places, blew the whistle on several beat cops who had been demanding payoffs for protection from police raids.

Another thread of Morphy’s account involves the introduction of narcotics into San Francisco in the 1950s—which, as the plot of The Gay Detective subsequently reveals, implicates nightclub owner Joe Cannelli and suggests his connections with Italian crime syndicates. This, too, has its correlates in San Francisco’s mid-century history. In an interview with historian Paul Gabriel on file at the GLBT Historical Society, former San Francisco Police Chief Tom Cahill describes how the Italian Mafia tried moving into San Francisco in 1948, with limited success. High-ranking police officers kept the airport under constant surveillance, and would meet suspected Mafiosi at the gate as they deplaned. In the days before the Miranda ruling, a great deal of information could be extracted from suspicious characters without paying as much attention to due process as we have become accustomed to in the past few decades. In Cahill’s words, there was a minor Mafia presence in San Francisco, but it “never got off the ground.”

Other oral history work does suggest that an Italian-connected narcotics ring operated out of Finocchio’s night club in the 1950s, though perhaps without the direct knowledge or involvement of owner Joe Finocchio, who was never personally implicated in any of the surviving accounts. One former performer there recalled how the club was always filled with men in “neon-lit suits” who did a brisk trade in drugs, and how a boyfriend she met there claimed to be involved in a drug-smuggling operation involving military personnel at the Presidio. Although no hard documentary evidence of Mafia-connected narcotics schemes in San Francisco’s mid-20th century gay subculture has come to our attention, there are at the very least suggestions in the historical record that the organized criminal activity Hogan describes in The Gay Detective had some basis in reality—or at least in the folklore of San Francisco’s queer community.

It seems significant to note as well that the struggle between cops and criminals portrayed in Hogan’s book carries overtones of ethnic rivalry—the crooks are Italian, while the crooked cops are Irish. Irish-Americans had in fact controlled the San Francisco police force and the vice trades associated with police corruption for decades, compelling members of other ethnic communities looking for a piece of the action to adopt a more entrepreneurial approach. Reading between the lines of Hogan’s suggestive comments, Irish cops (in his fictional Bay City, at least) regarded the gay life as part of the profitable underworld of regulated vice that was even then slipping away from them, while criminals associated with dope-pushing Italian mobsters tolerated—and to an extent catered to—homosexuals as an eminently exploitable class of people.

One of the most interesting elements of this power struggle, however, is that its battles are fought in a language that is neither Irish nor Italian, so to speak—but rather, the queen’s vernacular. This is precisely the point at which Francis Morley, the gay detective, appears on the scene. And while it is certainly true that Morley embodies the stereotype of the effeminate gay queen, at a telling moment in his dialog with the police and the FBI, Morley suggests that the persona of “queen” is a mask that he can drop at will:

“Gentlemen, let’s face it. Suppose we put it this way, and stop mincing words.”

Strangely, and surprisingly to his listeners, his words were now clipped and sincere, and his tone distinguished by a dangerously steely quality that they had not heard from him before.

“Our immediate target seems to be a gang, or organization, that blackmails and dopes the ‘boys.’”

Turning to the government agent, Francis continued, “I understand from what you said before that you tried to work your way into a few places, but just didn’t seem to fit. The point here seems to be that I look to be more the type, and can probably crash this outfit somewhere.”

It’s not too much to suggest that in this single scene in a critically dismissed book of lightweight genre fiction, published on the fly and promptly forgotten more than forty years ago, we can see the early glimmer of a new gay sensibility. In the briefest of moments, by artfully switching from queen to butch through the slightest adjustment of his vocal style, Morley reveals to those in power that their assumptions and perceptions of gay life have blinded them to one of the biggest developments in 20th century American urban culture—the emergence of a massive, politically savvy homosexual community. In the moment that Morley announces his intention to help ‘the boys’ we see that he is not interested merely in a few gangland murders, but rather in working to secure a safe haven for thousands of former chorus boys like himself who would call someplace like Bay City home.

That moment alone is worth the cover price of this Cleis Press reissue of The Gay Detective, but we trust you’ll enjoy the rest of the book, too, as you cruise the streets of San Fran …—er, we mean Bay City—with the fiercest, feyest private dick ever to sashay out of the Baths in the wee, dark hours of the early morn.