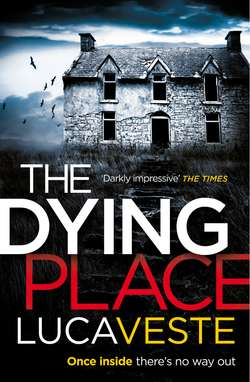

Читать книгу The Dying Place - Luca Veste, Luca Veste - Страница 15

5

ОглавлениеMurphy fiddled with the lever underneath the passenger seat, attempting to find the right motion which would move the seat backwards, removing his knees from underneath his chin. Sliding the chair back with a sudden bang, he ignored the stare from Rossi and went back to reading the criminal record of Dean Hughes.

It could have been his own from that age, had he not been much savvier. Every time Murphy had been in trouble as a teenager, he’d managed to get away with a warning here, a run away there. Not so much as an official caution, which was handy, given that he ended up joining the dark side himself.

Not that he saw it that way. The police service had given him purpose, a grounding. He could have been another lost statistic from the Speke estate. No drive to do anything other than get pissed with his mates and cause a bit of trouble. Boxing had helped, given him a sense of discipline, but when it became clear that he wasn’t going to make it above domestic level, he jacked it in. Waste of time.

Murphy remembered his dad talking to him once, dragging him out of bed at around ten in the morning, which had annoyed Murphy no end, given he hadn’t got home until four. His dad then had one of those conversations with him where he asked the questions Murphy had no answer for. What was he doing with his life … was this all he wanted … and where’s your keep, you little shit?

Just about to turn nineteen and he had no clue. Working every few days or so, cash in hand, and then blowing it on cider.

He couldn’t remember who’d suggested joining the police. It had just happened one day. He wandered into Canning Place near Albert Dock, having passed the initial application, and sat down to do a Maths and English test. Then it was the physical, which he’d passed with ease, still retaining the fitness from the boxing. Then two years on probation.

Fifteen years later and here he was, a detective inspector a good few years ahead of schedule, and at the forefront yet again.

‘What was the address again?’ Rossi said, disturbing Murphy’s trip down memory lane.

‘Clanfield Road,’ Murphy replied, checking the notes on the top of the file. ‘Head for Dwerryhouse Lane and I’ll direct you from there.’

‘Good, ’cause I get lost in all the back roads around there.’

Murphy sniggered, knowing what she meant. Norris Green was a larger place than most people expected. A council estate with one of the worst reputations in Liverpool at that moment – mainly for gang violence. Since the murder of a young boy outside a pub in nearby Croxteth, the result of a longstanding feud between rival gangs in Croxteth and Norris Green, with the eleven-year-old boy, an innocent bystander, shot in the back, the area had begun to change. Gangs had been shown on TV in exploitative documentaries – and subsequently shunned for revealing supposed secrets of ‘street-life’ – and the DIY show from the BBC had made over the local youth club, giving some kids a place to go which wasn’t in danger of falling down around them.

It was still a tough place to grow up though. Not much upward mobility in those kind of estates. And not many people trying to change that.

‘Take the next left,’ Murphy said, as they approached the end of Muirhead Avenue – Croxteth Park off to their right, still hidden by houses – the church where Dean Hughes’s body had been found that morning close by, only a few minutes further away.

‘Right here,’ Murphy said, looking at the derelict patch of field which lay to their left. An upturned Iceland shopping trolley was the main attraction, along with empty carrier bags, various bottles and rubbish. ‘You’d think they’d do something with that.’

‘With what?’ Rossi replied, indicating to turn.

‘That big patch of green. Just going to waste. It just looks like an eyesore, ’cause no one’s looking after it.’

‘You know why. They’re not willing to spend money around here. Reckon it’d just get wrecked, so they won’t bother.’

‘I suppose.’

Rossi slowed the car, looking for the right house number. ‘It’s bollocks though. That argument, I mean.’

‘You think?’

‘Course I do. If you put people in places like this, where everything is left to go to shit, what do you expect them to do? Everything’s grey, dark. That’s how your life is going to feel like. It’s the Broken Windows theory.’

‘The what?’

‘The theory that if the area you live in looks like shite, then the people who live there will act like shite as well.’

Murphy smirked. ‘And that’s how it’s put in the books, I imagine.’

Rossi snorted. ‘More or less.’

Murphy thought she had a point, but didn’t have chance to say so as she slowed the car and parked up.

‘I really wish we could have phoned ahead,’ Rossi said, unbuckling her seatbelt. ‘I hate just turning up with no warning. Makes it worse.’

‘Home number we had for them was out of use. Everyone has mobiles these days.’

The house they’d stopped outside of didn’t scream ‘house of a tearaway’. A sort of mid-terrace, with light brown stone brickwork. An archway separated the house from next door, but it was still connected on the top level. There were three wheelie bins on the small driveway, a few crisp packets lifting slightly in the breeze before settling back down against the fence. It was May, but Murphy shook his head as he noticed the house next door still had Christmas decorations hanging from the guttering – the clear icicles he’d noticed on market stalls in town, the previous December.

‘You ready?’ Murphy said as he pushed open the metal gate, the screeching sound as it slid across the ground making his hairs stand on end. It needed lifting, fixing or replacing.

‘Are you?’ Rossi replied, walking ahead of him and knocking on the door. Four short raps – the rent man’s knock, as his mum used to say.

They stood waiting for a few seconds before Rossi knocked again, pulling back as they heard the barking.

‘Porca vacca,’ Rossi said under her breath.

‘You don’t like dogs, Laura?’ Murphy said from behind a smile.

‘Not ones that bark.’

A few more seconds passed before they heard shuffling from behind the door. A mortice lock turning on the old-style door, the house not being adorned with one of the newer double-glazed models. It opened inwards a few inches, a face appearing in the gap.

‘Yeah?’

‘Sally Hughes?’ Murphy said, bending over so he wasn’t towering over the small-statured mother of Dean Hughes.

‘What’s he done now?’

Murphy raised his eyebrows at the instant recognition of them as police, even though they were in plain clothes. ‘Who?’

‘Our Jack. What’s he done? You’re either police or bailiffs. So he either owes someone or you’re trying to pin something on him.’

‘I’m Detective Sergeant Laura Rossi, this is DI David Murphy …’

‘Jack was here last night …’

Rossi held her hands out. ‘It’s not about Jack, Mrs Hughes. It’s about Dean.’

Sally opened the door wider, a look of resignation flashing across her face before she swiped her hand across her forehead, moving damp, lifeless hair away from her face. ‘Right. Well you better come in then.’

Sally walked away from them, locking the still-barking dog in another room before going through to what Murphy guessed was the living room on the left. He went in first, wiping his feet on a non-existent doormat without thinking and following her inside. He took the few steps into the living room, some American talk show snapping into silence as he walked into the room, the clattering of the remote control on a wooden coffee table.

‘Scuse the mess. Haven’t had chance to tidy up yet.’ Sally lifted a cigarette box and in a couple of smooth movements lit a Silk Cut and took a drag.

Murphy savoured the smell of smoke which drifted his way, before perching on the couch which was to the side of the armchair where Sally was sitting, legs tucked underneath herself.

‘What’s he done then? Haven’t seen him in months, so fucked if I know anything about it.’

Murphy glanced at Rossi, suddenly unsure how to proceed. If they opened with the fact Dean was dead, any information that may have been gleaned from a less stark opening might be lost. On the other hand, Murphy decided if his kid was dead, he’d want to know straight away.

‘We found a body in West Derby this morning, Sally. We think it’s Dean.’

The reactions are never the same each time. Every time a quiet difference. During his career, Murphy had experienced the whole gamut of emotions being projected in his presence; from howling tears of grief to quiet stoicism. He’d learnt to not really put much stock in the initial reaction, not to make assumptions based on them.

‘Fuck off.’

He’d not heard this one before.

‘Don’t be fucking stupid,’ Sally Hughes continued, laughing as she tried to take another drag on her cigarette, ‘look how serious you both are. Sorry lad, you’ve got the wrong house.’

Murphy breathed in. He’d seen the overall emotion of denial before – granted, it wasn’t usually accompanied by laughter, but once you got to the core of it, it was denial all the same. ‘Look at this picture for us, Sally,’ Murphy said, taking the blown-up, A4-sized photograph of Dean Hughes from the manila folder he was carrying. ‘Who do you see?’

Sally took a cursory glance at it, allowing her eyes to only alight on it for a few seconds. ‘Yeah, that’s not him.’

‘What about this tattoo?’ Murphy said, moving to another photograph which showed a tribal symbol found on the chest of the body.

‘Loads of lads his age have got the same thing,’ Sally said, still not looking at the photographs for more than a second.

Rossi moved out of the room beside Murphy, one quick glance passing between them. She’d be calling for support from family liaison officers, he hoped. Murphy leant forward, taking back the picture he’d handed to Sally and replacing it in the folder. ‘Sally, we think it is Dean, so someone is going to come and take you down the Royal to make an identification,’ – Murphy held up a hand to stop her interrupting – ‘and if it’s not him, then that’ll be it.’

‘It’s a waste of time, this. He can’t be there.’

‘Why not?’

‘He’s only missing. Probably getting into all kinds of shit.’ She stubbed out the cigarette into a clean ashtray. ‘But I’d know if anything bad had happened.’ She banged an open palm against her chest. ‘I’d know in here. I’m his mum. I’d know.’

Murphy watched as her hands began shaking, struggling to pass a hand through her hair to brush it off her face. Her eyes betraying her as they filmed over.

‘Sally …’

‘Don’t.’ She interrupted as he began to speak. ‘I’ll go down there, but I’m telling you, it’s a big mistake. Have you got kids?’

Murphy shook his head.

‘Then you wouldn’t know. I’m telling you, I’d feel it if he was gone. And I’m not feeling anything.’

Murphy let the silence hang in the air, staring at the crown of Sally’s head as she leant forward, both hands grasping at her hair before sliding down and crossing over so she was hugging herself. Murphy blinked, and believed she’d aged ten years since they’d walked through the door, realising quickly it was a trick.

‘They’re on their way,’ Rossi said softly, returning to the room. ‘Be about fifteen minutes. Do you want a tea or something, Sally, while we wait?’

‘It’s all right,’ Sally replied, forcing herself upright, ‘I’ll do it. You want one?’

Murphy shook his head, leaning back as Rossi followed Sally through.

Denial. He was sure it was on one of those lists about grief he’d once read. He just hoped acceptance wasn’t too far behind.