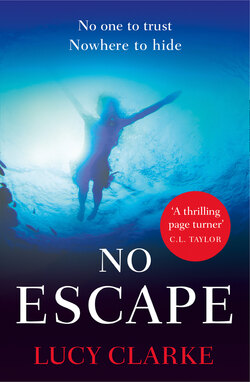

Читать книгу No Escape - Lucy Clarke - Страница 9

3 THEN

ОглавлениеLana woke to the sensation that she was swaying. A deep throbbing resonated through her skull and she lifted a hand, rubbing the heel of it against her forehead. Though her eyes were closed, she could sense sunlight and became distantly aware of an engine running and the sound of water nearby.

Gradually her eyelids peeled open – and she saw not walls or a ceiling, but sky. She blinked, squinting against searing daylight. A breeze brushed against her face and she tried to push herself upright, but everything seemed to move, tilt, swing. She struggled – but it was as if the bed, the very ground, was sinking away from her. Then she realized: she and Kitty were in a hammock. She turned her head, sending a new shock of pain around her skull, and saw sea, sky, the deck of a yacht.

‘Kit …’ she croaked.

Kitty came out of sleep as if she’d been plugged into the mains. She sat bolt upright, her hair wild, eyes wide. ‘Yes? What?’

Lana blinked again, searching out the harbour, the fishing bangkas, the town – but land was just a blur of muted shadows behind them. ‘We’re moving.’

‘Holy fucking shit! What happened last night?’ Kitty exclaimed, half-laughing.

‘Tanduay Rhum happened,’ Shell said, gliding across the deck barefoot, holding out two mugs of coffee.

Lana reached for one. ‘My God, you lifesaver.’

‘Have you kidnapped us?’ Kitty asked, taking her coffee.

Shell smiled. ‘Aaron wanted to sail to a spot up the coast on high tide, so he set out early. You’ll be back at the harbour by lunchtime.’

Kitty ran a knuckle beneath each eye and pulled on her sunglasses, which had miraculously survived a night on the hammock.

‘Were you okay up here?’ Shell asked. ‘I use the hammock when it’s too hot below deck, but it can get a little damp.’

‘I don’t think we’d have noticed where we slept,’ Lana said, looking out to sea as they were motoring forward. Then she manoeuvred her legs out of the hammock, wincing at the hot ache in her ankle as she stood.

‘How is it?’ Kitty asked.

Lana experimented with putting weight on it. ‘Not too bad.’

‘Good morning.’

Lana and Kitty both turned to see the Frenchman, Joseph, approaching. He had a thin, angular face and wore a rumpled shirt over a pair of shorts, his dark hair foppish and uncut.

‘Sorry I didn’t stay and meet you properly last night,’ Joseph said on reaching them. ‘You had a good time, yes?’

‘I think so – from what we can remember of it,’ Kitty replied.

‘We’re still trying to get our heads round the fact that you all live here, on this boat,’ Lana added.

‘Yes, me also.’ Joseph smiled. ‘We’re all lucky to have found it.’

She nodded in agreement. ‘How long have you been on board?’

‘Me – only five weeks. But very good five weeks. The others have been here much longer—’

Joseph was interrupted by a shout from Aaron. ‘Shell! Joseph!’

They all turned. Aaron was standing at the helm wearing a sun-faded cap and polarized glasses. There was something authoritative about his stance, the widely planted feet, the single hand resting on the wheel, the lift of his chin. ‘Let’s get the sails up.’

Joseph turned back to Lana and Kitty. ‘Time to see us at work.’

*

Sound filled Lana’s ears: the wild flapping of the sail as it was hoisted, the creak and strain of the sheets then the rush of wind as it filled the sail, making it snap out full and proud. The yacht heeled to the side and Lana gripped tightly to the wire lifeline that ran around the perimeter of the deck.

A moment later the engine was cut and the noise of the motor slipped away so that all that remained was wind and waves. She craned her neck, mesmerized by the muscular curve of the sail as it stretched into a cloudless blue sky.

Lana had never been on a boat – let alone a yacht like this – and she was awed by the sheer magnificence of being propelled through the sea by the power of wind. There was something so elemental, so stunningly powerful, about it. The wind toyed with the hem of her dress and mussed through her hair – and she breathed in deeply, filling her lungs with the warm salt air.

She looked down the length of the yacht, taking in the weathered teak deck where swathes of rope were neatly coiled, and a paddleboard and two surfboards were lashed to the railings with bungee cords. She thought, This is another life – another world.

Denny appeared from below deck wearing a faded grey trucker’s cap, his tight curls pinging out at the sides. His gaze found Lana and he smiled. ‘Joining us?’

‘Looks that way.’

Kitty and Lana watched as the crew moved expertly around the yacht – an effortless dance in which everyone knew their role. Barefoot and tanned, they seemed like an exotic race of travellers blown in from a faraway shore.

They’d been sailing for an hour when Denny pointed towards the front of the boat and said to Lana and Kitty, ‘You two should stand at the bow. We’ll be going close in.’

They picked their way carefully forwards, the breeze gently buffeting them both. Kitty slipped an arm around Lana’s waist, leaning her head against her shoulder. They watched the coast reveal itself until they were sailing towards a towering rocky pinnacle where trees and bushes grew at odd angles from cracks in the limestone.

‘Isn’t this insane?’ Kitty said. ‘Can you believe we woke up on a fucking yacht?’

‘I know,’ Lana grinned. ‘Beats waking up on a bus.’ Last summer they’d gone to a gig in London, and afterwards Kitty had talked their way onto the tour bus. They’d woken eight hours later at Wolverhampton Services with atrocious hangovers and only £23 between them to get home.

Beneath the sun, the sea glistened. Lana leant over, peering down at the shallowing water, which lightened to an aquamarine – coral wavering in and out of view as they glided forwards. ‘God, I’m so pleased we’re not in England.’

Kitty glanced at her sideways. ‘You feeling okay about everything?’

By everything, Lana knew that Kitty was referring to her father. ‘I am right now.’

The nose of the yacht drew so close to the rocks that Kitty suddenly stretched her hands into the air as if she could touch them. The yacht hugged the cliff line, and then it edged around a craggy point.

There, opening up before them, was an emerald-green lagoon framed by dramatic pinnacles rising out of the water. A serene white-sand beach curved between the pinnacles, backed by an impenetrable forest.

Kitty turned to Lana, grinning. ‘I think we’ve just stumbled across paradise.’

*

They anchored in the lagoon, then all crammed into the dinghy to go on shore.

When they stepped onto the beach, Lana dug her fingers through the sand, which was made of thousands of beautiful, tiny shells and fragments of white coral.

Shell lay a blanket in the shade beneath a palm tree, and Lana and Kitty joined her. They were still in yesterday’s clothes and were thankful to have been wearing their bikinis beneath them. Kitty tugged off her shorts and edged into the sun, lying back using her arms as a pillow, her stomach stretching taut. Lana remained sitting, propping her elbows on her knees as she listened to Shell, who was telling them the story of The Blue as she plaited fine strands of leather into a bracelet.

‘The first I heard of it was from a group of travellers in Vietnam. There’d been rumours about this floating commune of sailors, wanderers and adventurers. They said that they’d seen the yacht travelling around, and the crew were stopping at remote bays, anchoring off empty shores, sleeping under the stars, surfing crowdless breaks, fishing for their meals. To me it sounded like heaven,’ she said, her facing blooming into a smile.

‘So I travelled from Vietnam, heading west for Thailand in search of The Blue. I’m not sure I truly believed that it existed – but miraculously, I found her. She was anchored in a quiet bay in the west of Ko Samui. The moment I saw her I knew I had to find a way to get on board.’

Shell put down the leather she’d been plaiting and told them, ‘I swam out to the yacht and introduced myself to this guy sitting in the cockpit mending a sail – who happened to be Aaron. He was making a hash of the sail, so I showed him how to make a stronger pattern of stitches. My dad’s a sailor,’ she added, ‘so I’ve done my fair share of sail repairs. I spent the afternoon helping, and once the sail was fixed, I asked Aaron if I could join The Blue.

‘There weren’t any free berths at the time, but I said I was happy with the hammock. I spent the first three weeks sleeping beneath the stars, waking up covered in dew and mosquito bites – but I loved every moment. Then a Danish guy left and I took over his berth. That was fourteen months ago now.

‘Denny’s been here the longest: he joined Aaron in Australia. After him a couple of lovely Swiss girls joined. They left about three months ago.’ Shell confided, ‘I’m heartbroken. I was rather in love with one of them, Lea. Totally one-sided of course – she had a boyfriend back in Switzerland – but still, she was wonderful. There’ve been a few other crew – some stay for weeks, others for months. Heinrich’s been with us for almost six months now. He’s a good guy. Great to have around the boat. I swear he can fix anything – engine parts, cupboard doors, bilge pumps – you name it. Joseph is our newest crew member. He tends to keep himself to himself, but from what I can see, he loves being out here.’ Shell opened her hands and said, ‘So that’s all of us.’

Lana glanced across at Kitty. They held each other’s eye, a current of excitement firing between them as they both understood: they had to find a way of becoming part of this.

*

Lana fell asleep in the shade. She was awoken some time later by a dig in the ribs from Kitty, who whispered, ‘Where is everyone?’

Lana sat up, rubbing her eyes and squinting against the bright sun. Shell was gone from beside them and, as Lana took in the empty bay – the hard white of the coral sand, the clear blue water fringing the beach – she realized she couldn’t see any of the crew. The shoreline was empty. She and Kitty were on a deserted stretch of coastline, only accessible by boat.

Just as the first sparks of fear were beginning to ignite, Kitty suddenly pointed towards the left-hand side of the cove. ‘The dinghy. It’s still there.’

‘Jesus,’ Lana said, placing a hand to her chest. ‘You almost gave me a heart attack – I thought they’d left us.’

On the far side of the dinghy the crew were gathered in a circle, talking. Lana watched as each took turns to speak, their expressions serious. Denny sat with his arms folded over his lean chest, nodding. When Joseph was talking, Aaron turned to glance in Lana and Kitty’s direction. Lana wasn’t sure if he was looking at them or not, so she lifted her hand in an awkward half-wave. He didn’t acknowledge her, simply turned back to the others.

Shell had described the crew as wanderers and adventurers but, as Lana watched them, she wondered whether it was a thirst for adventure that had brought them out here – or whether they all had a reason for leaving their old lives behind.

‘It was the right thing, wasn’t it?’ Lana said suddenly, facing Kitty. ‘Leaving.’

The night that Lana had turned up at Kitty’s flat in a state of shock about her father, she’d made a decision that she was going to leave England. Kitty had held Lana’s shoulders, looked at her squarely and told her, ‘Then I’m coming, too.’

They’d talked further the following morning, Kitty ladling pancake mixture into a pan of hot oil as she confided, ‘I’ve been thinking for a while of giving up on the acting. It’s getting me down,’ she explained, tilting the pan so the batter spread evenly to the edges. ‘The auditions. The rejections. The bitching. Last week I turned up at an audition for a vacuum-cleaner advert – a fucking advert – and the guy said, “Come back when you’re not hungover.”’ Kitty had snorted. ‘I hadn’t even had a bloody drink! Can you believe that?’

‘What, that you hadn’t had a drink?’

Kitty had flicked out a hand and bashed Lana’s arm. ‘I’m just not sure I can face it any more.’

‘But you’re amazing at what you do.’

‘Am I?’ Kitty had said, loosening the edges of the pancake with a wooden spatula. ‘Maybe I thought I was at school, but in London every attention-seeking twenty-something seems like they’re trying to make it – and believe me, there are a lot of us. It’s hard, Lana. The constant rejections are crushing me. And … well, the thing is, I don’t even know what else I’d do. I’m not good at anything.’ Kitty flipped the pancake and it landed neatly back in the pan.

‘You’re a good pancake tosser.’

‘Curriculum vitae of Kitty Berry – experienced tosser.’

Over that long weekend in Kitty’s dingy studio-flat, while the rain fell in thick sweeps against the window panes, they’d spun the globe and concocted their plan to leave.

Lana had been surprised at how easy it was to dismantle her life. It’d taken a month to work her notice, move out of her shared flat, and sell her car. She and Kitty planned to start in the Philippines, and then travel on from there. They pooled their savings, then drew up a budget to see how long it would last them both, deciding to apply for work visas when the money ran out. They booked travel insurance, bought suncream, flip-flops and mosquito repellent, and had vaccinations for diphtheria and hepatitis A. The frenzy of activity was so consuming that Lana felt as if she hadn’t paused for breath until suddenly they were clanking down the metal plane stairway into the dense Filipino heat.

Now Kitty turned towards Lana, sunlight making her eyes glitter. ‘Leaving?’ Kitty repeated. Then her face bloomed into a smile as she said, ‘Best decision we’ve ever made.’

*

Lana waded into the shallows, feeling the cool grasp of the sea around her legs. Kitty hadn’t wanted to swim, so Lana pushed away from the shoreline alone, marvelling at the incredible feeling of weightlessness. When she was a little deeper, she ducked below the surface letting her body trail close to the seabed until her breath ran out.

She surfaced, then swam hard for a few minutes, feeling the muscles in her shoulders and legs tighten. When she reached a cluster of low-lying rocks, she pulled herself onto them, wrung the salt water from her long hair and leant back against the sun-warmed limestone.

Sometime later she saw a tanned back skimming along the surface, a snorkel pipe in the air. Denny lifted his head and, noticing her, he pulled the mask from his face, treading water.

‘See much?’ she asked.

‘Some amazing brain coral. Plenty of angelfish around, too.’ He clambered up the rock and plonked himself beside her, his shorts sending rivulets of water streaming towards her legs.

Looking down the line of her shins towards her feet, he asked, ‘How’s the ankle?’

‘Pretty good, thanks.’

His gaze shifted to her other ankle and he asked, ‘How long you had the ink?’

Lana looked at the black tattoo of a single wing of long black feathers. ‘Since I was seventeen. Kitty and I were supposed to get matching wings – but she fainted when she saw the tattooist’s needle.’

He laughed. ‘But you had yours done anyway.’

As they’d walked out of the parlour, Kitty had been bouncing around on the spot, saying, ‘I can’t believe you did it! Lana, you have a fucking tattoo! How cool is that? Your dad is going to go ballistic!’ But her dad said nothing. She wasn’t even sure he’d seen it. She went barefoot around the house, putting her feet up on the coffee table, but he either didn’t notice or simply chose not to pass comment.

Denny leant forward and placed his damp fingers on the tattoo. She felt heat spread from the point at which his skin connected with hers, and she stared at the spot as if she’d find it aglow.

‘It’s different,’ he said, looking at her sideways, and she couldn’t work out if he meant different-good or different-bad. She could feel warmth beginning to creep into her cheeks, and scrabbled to think of something to say. ‘Do you and Aaron know each other from back home? You’re both from New Zealand, aren’t you?’

‘New Zealand’s a big place,’ Denny said with an easy smile. ‘I joined The Blue in Australia.’

She nodded. ‘How do you all do this? This lifestyle that you have – sailing around the world with friends, living from one day to the next. It seems so …’ She paused, looking for the word. ‘… intangible.’

‘Intangible?’ Denny smiled, the sun catching in the golden hairs of his eyebrows. ‘I like that.’

‘But how do any of you afford it?’ she asked, then wondered if the question sounded rude.

‘We try and keep costs down, live simply. We all put in a hundred and fifty dollars a week to cover food, water, fuel and marina fees when there are any. If there’s anything left over it goes into the repairs fund. Some people had savings, plus we pick up work where we can. Like Shell – she makes jewellery and sells it in the tourist spots, and when we’re in port she teaches a few yoga classes, too. I know Joseph had some money put aside from before. I’m not too sure what Heinrich’s set up is; he said he’s going to be running dry soon. And then me – I work while I’m out here.’

‘Doing what?’ Lana asked.

‘I’m a translator. Of novels. French into English.’

‘I’ve never met a translator. What an interesting job,’ she said, looking at him afresh. ‘Is there an art to it? I can’t imagine how you go about replicating an author’s meaning in a different language.’

‘That’s what I love – trying to find the author’s voice and then convey it. Humour’s the hardest. It’s all wordplay and timing, which doesn’t always translate so easily.’

‘Where did you learn French?’

‘Went on a family trip to Réunion island as a teenager. It’s French-speaking. Loved it so much that I decided to study French for my degree as I got to spend a year of it on Réunion. After I graduated I worked in-house for a technical firm translating documents, but it didn’t suit me. Too much looking out a window longing to be someplace else, y’know? So I moved to fiction, went freelance.’

Lana nodded, understanding that longing to be somewhere else. She thought of the endless grey days at the insurance firm where she worked following her art degree – any hint of creative ambition stifled by the need to pay rent. She’d lived for her lunch breaks just so she could walk through the park and see daylight.

A loud whistle sounded from the shore. She turned and saw Aaron gesturing to the dinghy.

Denny glanced at her with something like regret in his expression. ‘Looks like it’s time to head back.’

*

It was mid-afternoon when The Blue returned to harbour. There was no mention of the girls joining the crew, and neither Lana nor Kitty felt comfortable asking. Aaron ran them ashore in the dinghy, and they sat together watching silently as the yacht shrank in their wake.

The noise and heat of town seemed to thicken the closer they drew to land, like a gathering thunderstorm. Lana’s earlier ebullience deflated as she thought of the sweltering heat of their guest room and the stringy kebabs they’d probably pick up for dinner in town after fighting their way through the crowds, street dogs and litter.

Aaron tied up the dinghy and held it steady as the girls climbed out. The ground seemed unstable after a night and day at sea and Lana felt as if she were swaying.

She hooked her bag across her shoulders, glancing at The Blue for a final time. The day had taken on a surreal quality – as if Lana and Kitty had swum into a dream from which they were only now waking.

Lana pushed her hands into the wide pockets of her dress and faced Aaron. ‘Thank you. It’s been an incredible day.’

‘Yes!’ Kitty chimed at her shoulder. ‘Amazing. Literally the best day of our entire trip. That beach was just … unreal. We’ll never—’

‘Be back here in two hours with your stuff,’ Aaron interrupted. ‘We set sail at eighteen hundred hours.’

Lana blinked, staring at Aaron. He was leaning back against the nose of the dinghy, arms folded across his chest, his face expressionless. ‘Sorry?’

Beside her, Kitty’s mouth was beginning to split into a smile. ‘Are you saying … we can join the crew?’

‘We took a vote on it and you’re in. Joseph is going to bunk in with Heinrich, so there’s a free cabin if you want it.’

‘Holy shit!’ Kitty exclaimed, clamping her hands over her mouth.

‘Are you serious? We can join the crew?’ Lana asked.

He nodded. ‘But I haven’t told you the conditions yet.’

‘Anything,’ Kitty said.

‘There are four rules. You break them, you’re out.’

They nodded vigorously.

‘One. Everyone pulls their weight – that includes cooking, cleaning, laundry, sailing, night watches – anything that needs doing. Don’t wait to be asked. Get stuck in. I know you don’t have any sailing experience, but I expect you to learn. Fast. Two. All important decisions are made by group vote – where we travel, what we buy, who comes aboard. Once made, the vote stands. Three. No relationships between the crew. We don’t need the complication.’

Kitty arched an eyebrow. ‘You run a celibate boat?’

‘I never said anything about celibacy. I just said no relationships.’

Kitty grinned.

‘And four,’ Aaron continued. ‘I’m not a nanny so don’t expect me to act like one. Everyone’s responsible for their own safety – we’ve got life jackets, harnesses, a life raft, flares and an EPIRB on board. Ask one of the crew to show you how they all work, and wear your life jacket or safety harness whenever you see fit.’

He ran a hand over the back of his head, the stubble of his shaven head scraping against his palm. ‘So what d’you reckon? Still coming?’

Lana turned and looked over her shoulder towards the yacht, a bright, effervescent sensation filling her. She found Kitty’s fingers and squeezed them tightly between her own. ‘We’re coming.’