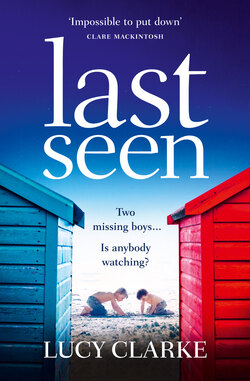

Читать книгу Last Seen - Lucy Clarke - Страница 10

Оглавление4. ISLA

My thoughts wander back through the events of this summer, turning each one through my mind, like a collection of pebbles I’m trying to arrange. I need to understand how I’m here. How any of this happened. Where everything went wrong between Sarah and me.

There was an evening jog in the mosquito-clouded air; a bottle of wine shared in the wrong beach hut; a stinging remark made on the deck of Sarah’s hut; a photo removed from a wall. Were those some of the events that led to this?

It wasn’t just this summer when things began to unravel – the first thread came loose years before. I meander further back through deep sands and beneath cloudy, salt-bitten skies, pausing on a boat returning to shore with only one boy on deck – not two.

There. That is the moment.

Maybe there’s a sense of inevitability, because how do you recover, pick up your friendship, after something like that?

Yet there was a time when Sarah was everything to me. When she was my family. Back then, I thought nothing could break us.

Summer 1997

My knees were pressed against the metal frame of my mother’s hospital bed, my hands squeezing hers. I was scared: scared by the smell of decay in the thick, still air; scared by the lightness of my mother’s fragile, bony fingers that had once danced with silver rings; scared by her tissue-thin eyelids that hadn’t opened in two days; scared by the watery rasp of her breath that dragged through her body like the tide drawing over rocks. I wanted to pull my hands away, clamp them over my ears. I wanted to run. I wanted to be anywhere but in the curtained space of a Macmillan ward watching my mother dying.

This could not be it. I wasn’t ready.

Our life together was walking at night through the woodland that backed on to our bungalow. It was reading books in front of the fire, me lying on the faded rug, my mother sitting in the oak rocking chair. It was picking elderflower heads and making thick sweet cordial that we stored in glass bottles in the pantry. It was strangers coming in and out of the house for Reiki appointments and reflexology. It was the smell of lavender and rosehip and orange blossom. It was the sound of laughter.

Cancer is a wicked thief. In four short months it had stolen almost everything my mother had: her energy, the songs she used to sing, the quickness in her steps. I’d watched her fade away until all that was left was her shadow. I knew the thief wouldn’t rest until it had that too, but I sat there, clinging on, not ready to let my mother go.

I squeezed her hand tightly, silently begging, I am nineteen years old. Don’t leave me, Mum. Please …

But she did.

She slipped away from me even while I was holding on.

A night-shift nurse with cropped black hair pulled the curtain back a little. Maybe that nurse had learnt to tell death from the expression on the living’s faces, or from the silencing of the hospital machines, or from that certain stillness that pervaded afterwards. She padded softly across the lino floor and gently placed her hand on my shoulder. ‘It’s all right, sweetie. You’re going to be all right.’

I didn’t move. Didn’t speak. Didn’t let go of my mother.

I screwed my eyes shut and gripped tighter, already beginning to feel her fingers cooling within mine.

On the afternoon of my mother’s funeral, I stood in the hallway, watching people trampling across our rugs, smearing our glasses with their fingerprints, leaving their scents of perfume and aftershave lingering in our home – wiping away the final traces of my mother.

I squeezed into the kitchen, skirting a group of my mother’s yoga friends, searching for Sarah. She’d slept at the bungalow with me every night since my mother died; we’d grab a stack of blankets from the lounge and sit on the mildew-ridden swing-chair in the garden, smoking and talking. I had no siblings to grieve with, and my father – a Scottish chef who’d met my mother during a retreat – had never been a fixture in my life. Sarah was everything, now. It was easy being together because she’d loved my mother, too. She’d tried on wigs with us, striking silly poses in front of the shop mirror; she’d artfully wrapped bright scarves around my mother’s neck to hide the tumours that had spread there; she’d smoothed blusher across her cheekbones before hospital appointments. My mother called her ‘Sarah Sunshine’.

I saw her across the room carrying a tray of drinks, smiling, thanking people for coming – doing the things I hadn’t the heart to. Seeing me, she tapped the pocket of her trousers where I could make out the rectangular shape of a cigarette packet, then signalled towards the garden with a grin. A smoke outside. That’s exactly what I needed. We’d pull down the hood of the swing-chair and light up with our heads bent together, shutting out the rest of the world.

As I started to make my way across the lounge, a heavyset man with tufts of white hair sprouting from the crown of his head lowered himself into my mother’s rocking chair. The oak spindles protested beneath his weight as he rocked it back and forth, the back of the chair clipping the wall with each motion. He lifted a hand to his mouth, inserting a forefinger to work something loose from his teeth, flashing his thick pink tongue at the room. He sucked his finger clean, then drummed it against the polished arm of the rocker, leaving a glistening smear of his saliva on the wood.

My throat burned with red-hot outrage as I bellowed, ‘No!’

The room fell instantly silent. Every head swivelled in my direction.

‘Get out of my mother’s chair!’

The white-haired man looked horrified. His brow dipped uncertainly, shock making his mouth hang slack. He pushed himself unsteadily to his feet, apologizing. His eyes darted around the room, as if looking for someone to help him.

A hand wrapped around my arm. Heart thudding, I turned to find Sarah looking at me, worry etched in her high, pale forehead. ‘Isla?’

An enormous pressure was building within my chest. ‘I … I just … need to go.’

‘Okay,’ she told me. ‘Okay.’

I spun round, crossed the living room and raced along the hallway, bursting out of the back door. A blast of cool air hit me, and I ran with my head down, my red pumps flashing along the damp pavement in quick bursts of colour, like a heartbeat.

Some time later, I found myself at the quay, my dress stuck to the small of my back, my breath coming hard. I gripped the metal railing, sucking in the salt-tinged air.

The beach huts sat quietly on the distant sandbank, a comforting presence with their pastel-light colours cutting through the grey, rolling sky. When the harbour ferry arrived, I didn’t pause to think about the guests abandoned in my home, or worry that Sarah would be left to lock up; I simply climbed aboard.

Within minutes, I was standing on the shoreline of the sandbank before a grey, restless sea. Tears ran down my face, dripping from my chin into the neckline of my dress. I had no coat, not even a cardigan, and I could feel the cold beginning to seep into my bones as I hugged my arms around myself, shivering into my sobs. When the first drops of rain began to fall, I stood firm thinking I could outlast them – that I would dance in the face of the cold, of the rain, my grief burning like heat inside me – but after a few minutes, the dark romance of the idea waned, and I hurried for cover beneath the pitched wooden roof of a beach hut.

Sheltering from the rain, I noticed a handwritten advert was tacked to the window, the blue ink faded: Beach hut for sale.

I stepped back, considering the hut. It had once been painted a brilliant blue, but the paint had peeled and flaked over the years. In places the wood had rotted, and the deck I was standing on had moulded in the corners, long fingers of dune grass reaching up beneath the planks.

There was a small gap at the base of the blinds, and I pressed my face against the damp glass, peering in. Through the dimness, I could see the deckchairs, a barbecue and a windbreak cluttering the small space. A sun-bleached sofa bed was piled with a rabble of patterned cushions. Above it was a driftwood shelf that had been emptied of the previous owner’s belongings, hardened candlewax pooled in two spots. At the back of the hut there was a small kitchen area with an ancient gas oven and a two-ringed hob. An old wooden spice rack was tacked to the wall, and an array of mugs hung from hooks below it. The mismatch of colours and patterns reminded me of my mother’s bungalow – and I wanted it.

I wanted that beach hut more than I’d ever wanted anything.

I could picture it: the hut would be a place to retreat to; somewhere I could rebuild myself; a place where I could watch the weather moving across the horizon and begin to make fresh memories.

As I stood on the deck of that old hut with the roar of the sea at my ear and the fresh breath of salt air on my skin, the sandbank seemed to stretch around me, holding me tightly, anchoring me.

Back then, I had been certain that buying the beach hut was the right decision. I used the money from the sale of my mother’s bungalow, though everyone had told me I was mad. Keep the inheritance in brick-built property – not a beach hut! But I was nineteen. I didn’t want mortgage repayments, council tax bills, or responsibility. I wanted the sea. I wanted space. I wanted to do something for myself.

Summers I’d live in the beach hut. Winters I’d rent one of the cheap holiday lets that always stood empty in the winter months.

It was a plan. It was the best I could do.

‘Go for it!’ Sarah had said to me as we ate Chinese takeaway sitting on the floor of my mother’s bungalow, surrounded by boxes marked for charity shops. ‘That’s what your mother would have told you to do, isn’t it?’

I nodded because she was right.

I remember how Sarah had put down her plate and slung her arm around my shoulder, pulling me in close. ‘The beach hut will be a fresh start, Isla. It’s going to change everything.’

Sarah was right about that, too.