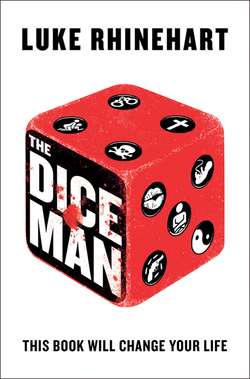

Читать книгу The Dice Man - Luke Rhinehart - Страница 14

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеAfter lunch I paid my ransom at the local parking lot and drove off through the rain for the hospital. I drove a Rambler American. My colleagues drive Jaguars, Mercedes, Cadillacs, Corvettes, Porsches, Thunderbirds and (occasional slummers) Mustangs: I drove a Rambler. At that time it was my most original contribution to New York City Psychoanalysis.

I went east across Manhattan, up over the Queensborough Bridge and down onto the island in the Eastriver where the State Hospital is located. The ancient buildings appeared bleak and macabre. Some looked abandoned. Three new buildings, built of cheerful yellow brick and pleasant, shiny bars, make the hospital appear, together with the older horror houses, like a Hollywood movie set in which two movies, ‘My Mother Went Insane’ and ‘Prison Riot’, are being filmed simultaneously.

I went directly to the Admissions Building, one of the old, low, blackened buildings which, it was reliably reported, was held together solely by the thirty-seven layers of pale green paint on all the interior walls and ceilings. A small office was made available to me there every Monday and Wednesday afternoon for my therapy sessions with select patients. The patients were select in two senses: one, I selected them, and two, they were actually receiving therapy. I normally handled two patients, meeting each for about an hour twice a week.

A month before this, however, one of my two patients had attacked a hospital attendant with an eight-foot-long bench and, in being subdued, had received three broken ribs, thirty-two stitches and a hernia. Since this was slightly less than he had inflicted upon the five attendants doing the subduing, no charges of hospital brutality seemed justified, and after his wounds healed, he was to be sent to a maximum-security hospital.

To replace him, Dr Mann had recommended to me a seventeen-year-old boy admitted for incipient divinity: he showed a tendency to act as if he were Jesus Christ. Whether Dr Mann assumed all Christs to be masochistic or that the boy would be good for my spiritual health was unclear.

My other QSH patient was Arturo Toscanini Jones, a Negro who lived every moment as if he were a black panther isolated on a half-acre island filled with white hunters armed with Howitzers. My primary difficulty in helping him was that his way of seeing the world seemed to be an eminently realistic evaluation of his life as it had been. Our sessions were usually quiet ones: Arturo Toscanini Jones had very little to say to white hunters. Although I don’t blame him, as a non-directive therapist I was a little handicapped; I needed sounds for my echo.

Jones had been an honors student at City College of New York for three years before disturbing a meeting of the Young Conservatives Club by throwing in two hand grenades. This act would normally have earned long tenure in a penitentiary, but Jones’s previous history of ‘mental disturbance’ (marijuana and LSD user, ‘nervous breakdown’ sophomore year – he interrupted a political science class by shouting obscenities at his professor) and the failure of the two hand grenades to maim anything more valuable than a portrait of Barry Goldwater, earned him instead an indefinite stay at QSH. He had become my patient under the questionable assumption that anyone who throws hand grenades at Young Conservatives must be sadistic. That afternoon I decided to let myself go a bit and see if I couldn’t provoke a dialogue.

‘Mr Jones,’ I began (fifteen minutes had already passed in total silence), ‘what makes you think that I can’t or won’t help you?’

Sitting sideways to me in a straight wooden chair, he turned his eyes at me with serene disdain: ‘Experience,’ he said.

‘That nineteen consecutive white men have kicked you in the balls doesn’t necessarily mean the twentieth will.’

‘True,’ he said, ‘but the brother who came up to that next Charlie with his hands not protecting his crotch would be one big stupid bastard.’

‘True, but he could still talk.’

‘No suh! We Niggahs gotta use our hands when we talk. Yessuh! We’re physical, we are.’

‘You didn’t use your hands then when you spoke.’

‘I’m white, man, didn’t you know that? I’m with the CIA investigating the NAACP to see if there’s any secret black influence on that organization.’ His teeth and eyes glittered at me, in play or hatred I didn’t know.

‘Ah then,’ I said, ‘you can appreciate my disguise: I’m black, man, didn’t you know that? I’m with –’

‘You’re not black, Rhinehart,’ he interrupted sharply. ‘If you were, we’d both know it and only one of us would be here.’

‘Still, black or white, I’d like to help you.’

‘Black they wouldn’t let you help me; white, you can’t.’

‘Suit yourself.’

‘That’ll be the day.’

When I lapsed into silence, he resumed his. The last fifteen minutes were spent with us both listening to the regular rhythmic shrieks from a man someplace in the Cosmold Building.

After Mr Jones left I stared out the gray window at the rain until a pretty little student nurse brought me the folder on Eric Cannon and said she’d bring the family to my office. After she left, I mused for a few seconds on what is called in the medical profession the ‘p’ phenomenon: the tendency of starched nurses’ uniforms to make it seem as if all nurses were bountifully blessed in the bosom and thus shaped like the letter ‘p’. It meant that doctors surveying the field could never be sure that a nurse they were flirting with was proportioned like two grapefruit on a stick or two peas on an ironing board. Some claimed it was the very essence of the mystery and allure of the medical profession.

Eric Cannon’s folder gave a rather detailed description of a latter-day sheep in wolf’s clothing. Since the age of five the boy had shown himself to be both remarkably precocious and a little simpleminded. Although the son of a Lutheran minister, he argued with his teachers, was truant from school, disobedient to teachers and parents, and a runaway from home on six separate occasions since the age of nine, the last episode occurring only six months before, when he disappeared for eight weeks before turning up in Cuba. At the age of twelve he began a career of priest baiting, which culminated in the boy’s refusal to enter a church again. He also refused to go to school. He was caught possessing marijuana. He was stopped in what appeared to be the act of trying to immolate himself in front of the Central Brooklyn Selective Services Induction Center.

Pastor Cannon, his father, seemed to be a good man – in the traditional sense of the word: a conservative, restrained defender of the way things are. But his son had kept rebelling, had refused to be treated by a private psychiatrist; refused to work, refused to live at home except when it suited him. His father had thus decided to send him to QSH, with the understanding that he would receive therapy with me.

‘Dr Rhinehart,’ the pretty little student nurse was saying suddenly at my elbow. ‘This is Pastor Cannon and Mrs Cannon.’

‘How do you do,’ I said automatically and found myself grasping the chubby hand of a sweet-faced man with thick graying hair. He smiled fully as he shook my hand.

‘Glad to meet you, Doctor. Dr Mann has told me a lot about you.’

‘How do you do, Doctor,’ a woman’s musical voice said, and I turned to Mrs Cannon. Small and trim, she was standing behind the left shoulder of her husband and smiling horribly: her eyes kept flickering off to a line of female hags who were oozing noisily through the hallway outside our door. The patients were dressed with such indescribable ugliness they looked like character actors who had been rejected for Marat-Sade for being overdone.

Behind her was the son, Eric. He was dressed in a suit and tie, but his long long hair, rimless glasses and sparkle in the eyes which was either idiotic or divine made him look anything but middle-class suburbanite.

‘That’s him,’ said Pastor Cannon with what honestly looked like a jovial smile.

I nodded politely and motioned them all toward the chairs. The pastor and his wife pushed past me to sit down, but Eric was staring out at the last of the women passing in the hall. One of them, an ugly, toothless woman with dish-mop hair, had stopped and was smiling coyly at him.

‘Hi ya, cutie,’ she said. ‘Come down and see me sometime.’

The boy stared a second, smiled and said, ‘I will.’ Laughing, he darted a bright-eyed look at me and went to take a chair. A juvenile idiot.

I plumped my big bulk informally on the desk opposite the Cannons and tried my ‘gee-it’s-wonderful-to-be-able-to-talk-to-you’ smile. The boy was sitting near the window to my right and slightly behind his parents, looking at me with friendly anticipation.

‘You understand, Pastor Cannon, I hope, in committing Eric to this hospital you are surrendering your authority over him.’

‘Of course, Dr Rhinehart. I have complete confidence in Dr Mann.’

‘Good. I assume also that both you and Eric know that this is no summer camp Eric is entering. This is a state mental hospital and –’

‘It’s a fine place, Dr Rhinehart,’ said Pastor Cannon. ‘We in New York State have every right to be proud.’

‘Hmmm, yes,’ I said, and turned to Eric. ‘What do you think of it all?’

‘There are groovy patterns in the soot on the windows.’

‘My son believes that the whole world is insane.’

Eric was still looking pleasantly out the window. ‘A plausible theory these days, one must admit,’ I said to him, ‘but it doesn’t get you out of this hospital.’

‘No, it gets me in,’ he replied. We stared at each other for the first time.

‘Do you want me to try to help you?’ I asked.

‘How can you help anyone?’

‘Somebody’s paying me well for trying.’

The boy’s smile didn’t seem to be sardonic, only friendly.

‘They pay my father for spreading the Truth.’

‘It may be ugly here, you know,’ I said.

‘I think I’ll feel right at home here.’

‘Not many people here will want to create a better world,’ his father said.

‘Everyone wants to create a better world,’ Eric replied, with a hint of sharpness in his voice.

I eased myself off the desk and walked around behind it to pick up Eric’s record. Peering over my glasses as if I could see without them I said to the father: ‘I’d like to talk with you about Eric before you leave. Would you prefer that we talk privately or would you like to have Eric here?’

‘No difference to me,’ he said. ‘He knows what I think. He’ll probably act up a bit, but I’m used to it. Let him stay.’

‘Eric, do you want to remain or would you like to go to the ward now?’

‘Full fathom five my father lies,’ he said, looking out the window. His mother winced, but his father simply shook his head slowly and adjusted his glasses. Since I was interested in getting the son’s live reaction to his parents, I let him stay.

‘Tell me about your son, Pastor Cannon,’ I said, seating myself in the wooden desk chair and leaning forward with my sincere professional look. Pastor Cannon cocked his head judiciously, crossed one leg over the other and cleared his throat.

‘My son is a mystery,’ he said. ‘It’s incredible to me that he should exist. He’s totally intolerant of others. You … if you’ve read what’s in that folder you know the details. Two weeks ago though – another example. Eric [he glanced nervously at the boy, who was apparently looking out or at the window] hasn’t been eating well for a month. Hasn’t been reading or writing. He burned everything he’d written over two months ago. An incredible amount. He doesn’t speak much to anyone anymore. I was surprised he answered you … Two weeks ago, at the dinner table, Eric playing saint with a glass of water, I remarked to our guest that night, a Mr Houston of Pace Industries, a vice-president, that I almost hoped sometimes that there would be a Third World War because I couldn’t see how else the world would ever be rid of Communism. It’s a thought we’ve all had at one time or another. Eric threw the water in my face. He smashed his glass on the floor.’

He was peering intently at me, waiting for a reaction. When I merely looked back he went on:

‘I wouldn’t mind for myself, but you can imagine how upset my wife is made by such scenes, and this is typical.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Why do you think he did it?’

‘He’s an egomaniac. He doesn’t see things as you and I do. He doesn’t want to live as we do. He thinks that all Catholic priests, most teachers and myself are all wrong, but so do many others without always making trouble about it. And that’s the crux. He takes life too seriously. He never plays, or at least never when most people want him to. He’s always playing, but never what he’s supposed to. He’s always making war for his way of life. This is a great land of freedom but it isn’t made for people who insist on insisting on their own ideas. Tolerance is our byword and Eric is above all intolerant.’

‘Sorry about that, Dad,’ Eric suddenly said, and with a friendly smile got up and took a position directly behind and between his parents with a hand resting on the back of each of their chairs. Pastor Cannon looked at me as if he were trying to read by the expression on my face exactly how much longer he had to live.

‘Are you intolerant, Eric?’ I asked.

‘I’m intolerant of evil and stupidity,’ he said.

‘But who gives you the right,’ his father said, turning partly around to confront his son, ‘to tell everyone what’s good and evil?’

‘It’s the divine right of kings,’ Eric replied, smiling.

His father turned back to me and shrugged. ‘There you are,’ he said. ‘And let me give you another example. Eric, when he was thirteen years old, mind you, stands up in the middle of my church during a crowded midmorning Communion and says aloud above the kneeling figures: “That it should come to this,” and walks out.’

We all remained as we were without speaking, as if I were the concentrating photographer and they about to have their family portrait taken.

‘You don’t like modern Christianity?’ I finally said to Eric.

He ran his fingers through his long black hair, looked up briefly at the ceiling and screamed.

His father and mother came out of their chairs like rats off an electric grid and both stood trembling, watching their son, hands at his side, a slight smile on his face, screaming.

A white-suited Negro attendant entered the office and then another. They looked at me for instructions. I waited for Eric’s second lungful scream to end to see if he would begin another. He didn’t. When he had finished, he stood quietly for a moment and then said to no one in particular: ‘Time to go.’

‘Take him to the admissions ward, to Dr Vener for his physical. Give this prescription to Dr Vener.’ I scribbled out a note for a mild sedative and watched the two attendants look warily at the boy.

‘Will he come quietly?’ the smaller of the two asked.

Eric stood still a moment longer and then did a rapid two-step followed by an irregular jig toward the door. He sang: ‘We’re OFF to see the Wizard, the Wonderful Wizard of Oz. We’re OFF …’

Exit dancing. Attendants follow, last seen each reaching to grasp one of his arms. Pastor Cannon had a comforting arm around his wife’s shoulder. I had rung for a student nurse.

‘I’m very sorry, Dr Rhinehart,’ Pastor Cannon said. ‘I was afraid something like this would happen but I felt that you ought to see for yourself how he acts.’

‘You’re absolutely right,’ I said.

‘There’s one other thing,’ said Pastor Cannon. ‘My wife and I were wondering whether it might be possible if … I understand it is sometimes possible for a patient to have a single room.’

I came around my desk and walked up quite close to Pastor Cannon, who still had an arm around his wife.

‘This is a Christian institution, Pastor,’ I said. ‘We believe firmly in the brotherhood of all men. Your son will share a bedroom with fifteen other healthy, normal American mental patients. Gives them a feeling of belonging and togetherness. If your son feels the need for a single, have him slug an attendant or two, and they’ll give him his own room: the state even provides a jacket for the occasion.’

His wife flinched and averted her eyes, but Pastor Cannon hesitated only a second and then nodded his head.

‘Absolutely right. Teach the boy the realities of life. Now, about his clothing –’

‘Pastor Cannon,’ I said sharply. ‘This is no Sunday school. This is a mental hospital. Men are sent here when they refuse to play our normal games of reality. Your son has been sucked up by the wards: you’ll never see him the same again, for better or worse. Don’t talk so blithely about rooms and clothes; your son is gone.’

His eyes changed from momentary fright into a cold glare, and his arm fell from around his wife.

‘I never had a son,’ he said.

And they left.