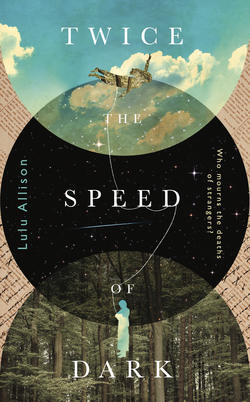

Читать книгу Twice The Speed of Dark - Lulu Allison - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

For two days Anna stays at home, ignores the phone. Ignores the voice that, like a concerned friend, suggests she call someone. Anna dismisses this friend and does not call others. She pulls curtains across the short days of winter, exhausts herself with afternoon and late-night drinking. The clatter of television and the taut thrum of a headache distract her as she writes in the bluebell-coloured book or gazes in mute distraction out of the window. She avoids the fatal impact of her thoughts by breaking them into small pieces, a burying, weighty gravel of fragments. If only she could block out the world, achieve some form of oblivion. The seedy realm of daily drug use promises a reliable form of unconsciousness, absence from here. That strategy provides a good thick and grimy wall between all of this and all of that, no details too distinguishable. Tempting maybe – but who is she kidding? The occasional heavy hand on the whisky pour, as evidenced by the last few days’ headache, is as far as she has ever ventured in that direction. She is too conventional, too afraid of death and too fearful of breaking laws, putting this reliable form of oblivion beyond her reach. Her imagination offers a retreat of sorts, a world where the sorrows of others require her notice and her compassion. She finds relief in offering them that small care, in wandering the now-familiar paths she has made, walking the woods, telling and retelling herself their lives. She retreats into the world of her shades, imagines how their lives would be if she had invented them as living people, not markers of the dead. There is at least space and calm in that sad realm. She ventures out to the woods, kept safe in their company from being haunted by her own memories.

The day is crisp and cold. The air is brittle, frozen thin, the tree trunks like metal. Victorian cast-iron pillars holding up a shelterless trellised roof. Christmas is nearly here again. Oh God, she wishes there were a hotel underground somewhere. No phone signal, no eyes to meet, no friendly enquiries about well-being and plans for the day. Just reclusive efficiency and a decent restaurant. Just a place to hide. Last year, the card from Michael’s grandchildren (step-grandchildren, though he does not recognise the offset), she struggled not to burn it. What was he thinking? She doesn’t think she has even met them.

She pulls away, sets her jaw again. Clenches her teeth and walks faster. There is a tart silence in the woods in this cold, broken only by small snaps of twig and freeze-dried leaves underfoot. Nothing, as she stops walking to examine her ankle, turned on a stone. There is pain but no damage. She walks on; leaves break again, small snaps under each step. She fills her thoughts with the people she will write in the new book later in the day. Twenty-nine killed by a suicide bomber. It is too many for her, too gruelling. She knows the limitations of her own accounting. But she sees some of them.

A girl, slender as willow, about twelve years old, hair that clouds around a face not yet firmed for adulthood. Now she is dressed for school, hair braided and tucked away, neat schoolwork tucked in her bag. She is a diligent worker, when unscripted dreams don’t pull her away out of the classroom window to fly, storyless, with the birds.

An old man, bent and fragile, curved like the corner of old paper. He walks each day, a slow shuffle through his now-tiny world. One of his grandchildren, a boy of eleven, walking in patient companionship with the beloved old man. He had been showing him a new knife, that most prized of possessions for a young boy. His knife will be picked up and vehemently cherished by one of the men who tries and forever fails to make sense of what was left in this broken arena.

A happy man, energetic and sprightly. He chats cheerily with the various food sellers, many he knows by name. He is on his way to a bookshop to collect an order, and plans to get flowers for his wife on the way home, to celebrate the birth of another grandchild. He tells the vendors of his good fortune. A girl with her dark hair neatly held under a pearl-grey headscarf. Her young and secret heart, her loves and friendships, her talent for maths. The girl stands in the cold, silent and afraid, framed by gateposts of beech. Anna tells her not to worry, she will be all right. She wishes she knew it to be true. A man whose life spins out before him, a mosaic of impenetrable design. A colourful, senseless, perhaps beautiful pattern. Fragments and tiles arranged, it seems to him, by another, mightier hand. He too is dead, his patterns dark forever.

A young woman, nineteen. There she is; she tries to sneak in, disguised a little here and there. But she is too familiar, too close. Her long limbs, her eyes the indeterminate colour of a river. She bubbles up through the dead before Anna’s eyes.

Anna stops, too close to summoning from memory rather than imagination. The shock of seeing Ryan has taken a sledgehammer to her defences. Damage has been done, walls are breached, doors cracked. Caitlin flits through the smallest chink, a wraith, a twist of pain.

Anna leans on a broad trunk, glad of its steadying girth. She focuses on the tree beneath her suddenly feeble hand. The tree has decades of practice in not losing its place, its place right there, that piece of earth and that piece of sky, roots and canopy held together by the steady trunk. She leans in, borrowing its expertise in being still, solid, placed, marshalling her evasions. She swallows, waiting until her mind is clear of trespassing memory, concentrating on the solid print of bark under her hand, pressing hard for more steadying contact. After a small while she peels her gloved palm from the kind tree and once more resumes her communion with the dead of her own reckoning.

*

I sift the ribbons, follow – feel along them. I try to find the one that links the beginning to the end. I imagine the change of colour, the loss of lustre, the fray and warp and pull. It started so well. Golden. I have never felt happier than during that golden summer infused with the blessing of love, overwhelmed with it. Gilded months of clarity and certainty, crystalline, languid and plentiful. I still long for that. Not for the love of Ryan. For the love of love. I could still stroke that soft, golden streamer for the beauty of it, even knowing how knotted and ugly it became. But he made it so. He was the stain and the fray. Love is not a destiny that fulfils itself; it is a gift to be born and cherished. Love was given to me and Ryan as a gift. He beat it into a curse. Perhaps it is only us, the cursed, who serve out death in this spinning, chaotic reel through the blackness. Maybe death for others is a serene, wholesome arc. Sleepily adrift, they disappear in bliss. Perhaps.

I brush past another sometimes, but they spin like me. I cannot gather enough of myself in to ask them what they know. I don’t even know, were I to find the mouth to speak, the lungs and throat to make the sounds, if sound is possible. Perhaps there are ways, new ways I will learn after millennia of spinning silently, new ways to make communion with another. Perhaps there will be things shared again. I sense them; we mingle, combine, rush through each other as we spin out alone to yet another far reach or dark and distant corner. Who knows if we yet have the option to communicate.

I feel my fingerless way along the knotted snags, the gnarled and stained bandage, gruesome tapes that loop round and lead backwards from my ugly death. Ribbons threaded through wooden hearts. Crime scenes. I find my way backwards so that I may tell forwards. Memories can be hard to find; stories and understandings shiver, slide into view and are lost again. I know it is all there, and I will find my tale. Though it is a labour, a stagger up black, vacuum-formed mountains, pulling hand over hand through gullies carved into the cosmos, harsh channels sharper and more lacerating than any earthbound stone. I pull against the blackness that would once more fling me out past the centurion path of comets, further than the spacebound eyes of man can reach. I don’t want to disappoint, but there is nothing to tell. There is more of the same. There is still no place in which I may claim to be. I don’t want to disappoint, but I have seen nothing that seems to be a heaven. Only Earth, with her kind sky and her care-giving cradle of gravity and her beautiful sun. How blessed I am when I find her again. How hard I cling.

I will try to tell it all, how it all happened. But you will have to be patient. I cannot say which bits I will be able to find, which will be torn again from my grasp before I can account for them, which I will miss altogether. We may have to wait for the giddy carousel to swoop round once more. I will try to make my remembered fingers grasp the streamer, pull it out of the blackness for you to see.