Читать книгу The Complete Book of Chinese Knotting - Lydia Chen - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChinese Knots in Ancient Times

Chinese knotting, ancient as it may be, was never the subject of scholarly treatises and there are only passing references to it in the literature. Some scholars believe this is because the early Chinese looked down on science, technology and the folk arts, believing that “Philosophy is the Way, and all others are just tools.” Yet, the complexity and ingenuity of the knots that have survived from the late Qing and early Republican periods as well as tantalizing secondhand evidence from sculpture, stone carvings, paintings and poetry testify to the culmination of a long, unbroken artistic tradition that may possibly have predated the written record.

From early times, knotting was one of the most basic skills that Man needed for survival. It was only after knotting techniques were developed to bind two or more things together that he could invent a variety of tools for hunting and fishing, such as bows, arrows and nets. Mankind went on to make farming tools, such as hoes and shovels, by fastening stones to wooden sticks, which led, in turn, to the construction of shelters using cords to bind the different members together, and the development of other inventions to aid production and convenience. Eventually, knotting became developed for communication purposes, to exchange letters and numbers and to record events. The art of knotting gradually found its use in decoration and rituals, firmly establishing itself as an important part of traditional handicrafts.

Using Cords to Record Events

Although it is difficult to envisage, there is sufficient documentary evidence to show that the ancient Chinese recorded events with cords. In a commentary by an early scholar, Zhou Yi, on the trigrams of the Yi Jing or Book of Changes, the oldest of the Chinese classic texts, which describes an ancient system of cosmology and philosophy that is at the heart of Chinese cultural beliefs, he says that “in prehistoric times, events were recorded by tying knots; in later ages, books were used for this.” In the second century CE, the Han scholar Zhen Suen wrote in his book Yi Zu, “Big events were recorded with complicated knots, and small events, simple knots.” Chapter 81 of the Tsui Chronicle also records that “... no writing, hence must carve on woods and tie cords....” Moreover, the chapter on “Tufan” in the New Tang Chronicle reveals that due to a lack of writing, the ancient Chinese tied cords to make agreements. This was practiced in other countries as well. For example, in Peru, there was a similar system called “Qui’ pu,” whereby a single knot means 10, a double knot 20, and multiple knots 100. Special government officials were available to explain the knots. The only indigenous evidence of this practice of making records with knotted cord consists of simple pictorial representations of the symbolic use of knotting on the surface of bronzeware from the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE).

Ancient calligraphy from the late Western Zhou Period (770–256 BCE) in the 12th year of Emperor Wei’s reign.

Calligraphy from the 27th year of Emperor Wei’s reign.

Calligraphy from the 31st year ofEmperor Wei’s reign.

Jade xi tools in the shape of a phoenix and dragon, Warring States Period (475–221 BCE).

Knots in Stone Carvings and Fabric Paintings

The double coin knot is the oldest knot to be recorded, although the prototype, a series of vertical double coin knots found on a pedestal box excavated from Zhao Qing’s tomb in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province (page 2), appears to be more of a design concept than an actual knot. A stone carving depicting a single dragon and two dragons intertwined at their tails, taken from the relic site of Xianyang Palace, Shaanxi Province, dated to the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE), is thought to bear a strong correlation to the fabric painting depicting two dragons in the shape of a double coin knot at Ma Wang’s tomb in Changsha, Hunan Province (page 10). More specific correlation can be seen in the recent discovery of stone and brick carvings at the Western Han tombs in Henan Province or the Eastern Han tombs in Shandong Province. In these artifacts, we can see double coin knots in the form of intertwined dragons (page 2) or the intertwined ancient deities Fu Xi and Nu Wo in the form of a human head linked to a dragon’s body (page 10). (Nu Wo was the ancient goddess who created Man with mud and cords.) The carving of the intertwined Fu Xi and Nu Wo, besides showing them as the initiator of marriages, also signifies that the Chinese are descendants of dragons. This is one reason why the double coin knot is the love knot popularly referred to in ancient poems. In the stone carvings at an ancient tomb in Shandong, dated to CE 424, Six Dynasties Period, we can see a multiple double coin knot in the form of four intricately intertwined dragons (page 11). Apart from double coin knots, other Chinese knots are depicted in frescoes, for example, the button knot in a stone carving from Shandong (page 3). In terms of structure, the button knot and double coin knot belong to the same system; the former is, in fact, a variation of the latter.

Cords tied in this way show the number of cattle, goats and horses in Okinawa, Japan. This indicates a total animal count of 188.

Part of a fabric painting depicting two dragons intertwined in the shape of a double coin knot, Western Han Period (206 BCE–CE 8), from Ma Wang’s Tomb, Changsha, Hunan Province.

Rubbing from a decorative brick, Han Dynasty (206 BCE–CE 200), from Yang Kuan Temple, Nanyang, Henan Province.

Rubbing from a stone carving depicting the Superior Mother Goddess, Deity Fu Xi and Goddess Nu Wo intertwined in a dragon’s body in the shape of a double coin knot, Eastern Han Period (CE 25– 220), from Tung Wei Mountain.

The Poetic Use of Chinese Knots

According to the Ci Hai dictionary, a knot is the hook-up of two cords, and hence the knot has always been euphemized as the love between a man and a woman. The famous Tang Dynasty poet Meng Jiao wrote in his poem “Knotting Love”:

One knot after another

Knotting true and deep love

Upon my love’s departure

I make a thousand knots on his sleeve

I swear to wait faithfully

Hope these knots will prompt him to come home early

But what’s the use of tying knots on his garment?

It is better to knot our hearts together

We knot our hearts in whatever we do

We knot our hearts for eternity

The love knot has always been synonymous with true love. The Ci Hai goes on to explain that “In ancient times, gold cords were intertwined countless times to signify true love, and thus were appropriately euphemized as the love knot.”

Among Chinese knots, the double coin knot most resembles the love knot, another reason for us to extrapolate that the love knot mentioned in ancient poems is actually today’s double coin knot. Indeed, the love knot is the earliest knot mentioned in ancient poems, such as “Yu So Si” by Emperor Liangwu of the Southern Dynasty, “Dao Yi” by one of China’s most renowned poets, Li Bai, “Willow” by Liu Yu Xi, “Farewell Song” by Wang Jian, “Spring in Wulin” by Ou Yang Siu and “To the Pipa Girl” by Li Qun Yu. In each case, the poet revealed his love with the love knot. In Meng Liang, Wu Zhimu wrote that in ancient marriages, the red cloth covering the bride’s face was graced with a double love knot, as were the bride and bridegroom’s wine cups, which were quickly drained and turned upside down under the bed for good luck.

Besides the love knot, there is the happy together knot mentioned in Emperor Liangwu’s poem “The Autumn Song.” We do not know what the happy together knot looks like. However, the History of the Liao Kingdom mentions that every year, on May 5th, the Liao people tied cords of five different colors on their arms and called this the happy together knot. Given that the Han and Liao used their knots for different purposes, the two happy together knots may be altogether different.

There is a third knot that is quite similar to the love knot, the pair knot. In his poem “Jie Yang Chang,” Jie Xi Si of the Yuan Dynasty mentioned the pair knot. Also, Li Bai, in his poem “Dai Zheng Yuen,” talked about another knot which he euphemized as the huiwen knot. It is likely that this huiwen knot is actually the love knot, a case of a single entity with two names.

Rubbings of stone carvings from an ancient tomb in Changsan, Shandong Province, showing multiple double coin knots in the shape of intertwined dragons, Six Dynasties Period (CE 265–589).

Detail of a painting, Five Dynasties Period (CE 907–960).

Detail of a painting,“Li Gao Listening to Ruan,” Song Dynasty (CE 960–1279).

Knots in Everyday Life

Through China’s long history, knotting gradually developed into a distinctive decorative art, generating countless fashion, household and ritual items used in royal temples, palaces and in the homes of common folk, and also to make a special occasion even more wonderful. Knots were cherished not only as symbols, but also as an essential part of everyday life, and were used to decorate lanterns, musical instruments, fans, dresses, chopsticks, sachets and many other items.

Prior to the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–CE 220), Chinese knots, though limited to the double coin knot and its derivative, the button knot, commonly graced the jade and copper ornaments (page 12) as well as mirrors (page 14) and seals. Long strings of jade secured with knots on an Eastern Zhou Period (770–256 BCE) wooden figure from the Chu tomb, Xinyang, Henan Province (page 14) testify to an even earlier decorative knot-making tradition in China.

The decorative function of Chinese knots became more pronounced in the Six Dynasties Period (CE 265–589), as seen in the pillar depicting three consecutive double coin knots and a compound double coin knot comprising four interlocking dragons in the Southern Dynasty tomb in Changsan, Shandong (page 11).

Chinese knotting peaked during the Sui and Tang dynasties (581–906), when numerous basic knots – sauvastika, cross, round brocade and tassel – and one that looks like a cloverleaf with two outer loops – were used to adorn palace objects. In the ensuing Song Dynasty (960–1279), these single knots were replaced by multiple knots. The true cloverleaf knot also appeared. Though none of the present day knots appeared in the late Song-early Yuan dynasties, this period had one very unique decorative knot which we do not yet know how to tie. We do not see a lot of knots adorning everyday objects in the Ming Dynasty (1369-1644), except for the pan chang, an early example being the strand of pan chang knots on the screens behind imperial portraits (page 6).

The Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) witnessed a second peak in the use of knots. During this time, all present day basic knots became widely used. We can even see some outer loops being extended into complicated knots.

Buddhist statue, Western Wei Dynasty (CE 535– 556), from cave 102, Maiji Caves, Tianshui, Gansu Province.

Copper ornament, Han Dynasty 206 BCE–CE 220).

Right: Stone carving entitled “The Empress’s Devotee,” Northern Wei Dynasty (CE 386–534), in Bingyang Cave, Longmen Grottoes, Luoyang, Henan Province.

Far right: Portrait entitled “Seated Folks,” Southern Song Dynasty (CE 1127–1279). Photo courtesy Palace Museum, Taipei.

Clothing

Long robes with flowing sleeves, the traditional garb of both men and women in ancient China, had to be fastened at the waist with knotted sashes. Simple examples exist in paintings (pages 11 and 12). Gentlemen of the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1050–256 BCE) would carry a special device, a xi (page 9), tied to their waist sashes for untying knots. They were also fond of wearing elaborate belt ornaments hung from their sashes, composed of several small pieces of delicately carved jade with cord eyelets strung together with intricate knotwork.

Tang sculpture has preserved the designs of a handful of knots, some quite complex, that have survived to the present day. The prototype of the good luck knot (with only one layer of overlapped ear loops) can be seen in a hanging tassel on a statue of the Goddess of Mercy, Kuan Yin, dated to the Northern Zhou Period (page 3). Subsequently, the Buddha knot, which Buddhists hold as a symbol of all good fortune, was spotted hanging from the waist of another statue of Kuan Yin, dated from the Sui Dynasty, now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City (page 4). The double connection knot was first discovered decorating the back of a sash on a Tang terracotta figure housed in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (page 4). On the same tassel is a Buddha knot. Indeed, a few double connection knots with outer loops, of which the knotting technique still remains elusive, are apparent on various stone Bhodisattvas from the Western Wei and Northern Qi periods (mid-sixth century). An elegant knot was found on the tassel of the empress’s devotee on the stone carving of the same name found in Bingyang Cave, Luoyang (page 12). The cross knot made its debut on a Tang Dynasty silk belt in the Tokyo National Museum. The image on page 4 shows a net bag tied from cross knots.

In the Southern Song portrait “Seated Folks” (page 12), some double connection knots with outer loops are clearly visible on the characters, but the knotting technique still eludes us. Since it only appears around the Southern Song–early Yuan period, it can serve as a diagnostic indicator for other artifacts.

Detail of a portrait,“The Lady with the Fan,”Tang Dynasty (CE 618–906).

Rubbing of the “Seven Scholars of the Bamboo Garden,” rubbing from a brick frieze, Danyang, Jiangsu Province.

Stone frieze entitled “The Emperor Praying to Buddha,” Bingyang Cave, Longmen Grottoes, Luoyang, Henan Province.

Ru yi (sacred fungus) knot, Tang Dynasty (CE 618–906). Photo courtesy Palace Museum, Taipei.

Furniture and Other Household Objects

Bronze mirrors, forged with rings on the back, were tied to walls by knotted cords (page 14), while bronze vessels from the Warring States Period, replicas of earthenware jugs, were decorated with a knotted network resembling the cords used to support their fragile antecedents. In various portraits from the Tang and Five Dynasties periods, Chinese knots occur beneath chairs, for example, in “The Lady with the Fan” (page 13), and in screens behind emperors’ seats. In fact, the first pan chang knot was found in a portrait of the Ming Emperor Xiaozhong (page 6). From the Song period, Chinese knots were used to decorate armrests. The predilection for Chinese knots is evident in all portraits of Song royalty, for example, Empress Zheng Zhong (page 14).

Accessories and Other Items

Umbrellas adorned with Chinese knots are abundant in the “Luo Goddess” scrolls dated from the Eastern Jin Period. They are also seen in the stone frieze, “The Emperor Praying to Buddha,” in the Bingyang Cave, Luoyang, Henan (page 13). Musical instruments embellished with knots can be seen in the brick frieze, “The Seven Scholars of the Bamboo Garden,” from Hu Bridge in Danyang, Jiangsu (page 13). During the Qing Dynasty, knots were widely used to grace objects in daily use such as ru yi, sachets, wallets, fan tassels, spectacle cases and rosaries. All existing basic knots, except the creeper and the constellation knots, also appeared on ornaments from the Qing Dynasty, regarded as the heyday of Chinese knots, where the outer loops were extended into other knots. As a decorative design on objects, the round brocade knot was first discovered on a Tang silver pot dug up in He Village, Xian (page 5). The tassel knot was discovered onTang a mirror (page 5) and the cloverleaf knot on a Song porcelain box (page 6).

Portrait of the Empress Zheng Zhong, Song Dynasty (CE 960–1279).

Longevity mirror, Han Dynasty 206 BCE–CE 220). Photo Courtesy of Palace Museum, Taipei.

Painted wooden figure, Eastern Zhou Period (770–256 BCE), from the Chu tomb, Xinyang, Henan Province.

Sketch of the same wooden figure.

Special Characteristics of Chinese Knots

In the realm of knotting, Chinese knots are considered to have the most outstanding decorative value. Even the Japanese and Koreans – themselves masters at tying knots – are fascinated by the knotting techniques and applications of the Chinese for the simple reason that the structure of Chinese knots is highly varied and their applications limitless.

Chinese knots are not only exceptionally graceful but are also practical: they can tie objects tightly. A major characteristic of Chinese knotwork is that all the knots can be tied using one cord, usually about a meter in length. Another is that every basic knot is named according to its distinctive shape, meaning or pronunciation. A Chinese knot body is made up of two layers of cords sandwiching an empty space, hence the three-dimensional, symmetrical body is tough enough to stay in shape when suspended. Redundant cord ends can be hidden inside a knot body and ornamental beads, precious stones or other embellishments can be incorporated for additional aesthetic effect. Since all Chinese knots are identical on both sides, they are pleasing to the eye.

Chinese knots also have unlimited variations due to their complicated weaves and weave sequences, the number of outer loops employed, the tightness of the knot body, etc. Furthermore, the basic knots can be randomly recombined to form many more patterns. All Chinese knots can be used to decorate and tie objects. The scope of ingenuity in Chinese knotting is thus without boundaries.

Knotted masterpiece by Sekishima Noboru.

A study in simplicity and elegance by Sudou Kumiko.

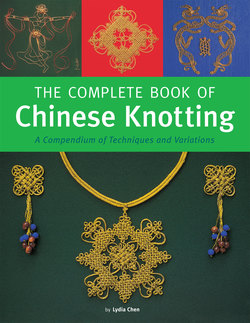

Knotted gold thread pendant by Lydia Chen.

Chinese knot wall décoration by Lydia Chen.

A wall hanging made of flat knots and rolling knots, courtesy of Tanaka Toshiko.

A stunning knot encircling a bead by Lydia Chen.

Korean examples by Kim Ju-shen.

In his book Japanese Gift Wraps, Sekishima Noboru expounded that the Japanese tradition of tying knots, hanamusubi (hana means “flower” and musubi “knot”) was, in fact, a legacy from China’s Tang Dynasty. This occurred in the seventh century when the Japanese Emperor, impressed with the elegance and practicality of the reed and white jute cord knots used to tie a gift from the Chinese, encouraged his people to adopt the same practice. However, the Japanese knots that developed as a result tend to be comparatively austere and formal, perhaps because of the constraints in Japanese tradition and the overall Japanese aesthetic. Up to this day, Japanese knots are still fairly simple and structurally loose and are more decorative than practical in function. They are embedded in everyday activities such as wrapping. The use of numerous colors and diverse types of cord are particular Japanese characteristics.

Closely related to Chinese knotting is maedup or Korean knotting. As with Japanese knots, it is believed that Korean knotting techniques originated from China. According to the late Kim Ju-shen, one-time president of the Korean Handicraft Association, historical data about Korean knots is grossly lacking and their origin and use in ancient times is unclear although it appears that they are based on Chinese antecedents. However, Korean knots have evolved into a rich culture of their own in terms of design and color and the incorporation of local characteristics. The main differences between Chinese and Korean knots are the proportion of tassel to knot (much longer tassels are used in Korean knots), the type of cord used (Koreans favor round braided cord), and color (Koreans tend towards the five primary colors of red, yellow, green, blue and black and often use all five in a single knot).

Unlike Chinese knots, Western knots, the best known ones being the two-dimensional flat knot and curled knot, are very simple and repetitive – almost monotonous. Not a great deal of skill is needed to tie them. Moreover, they are neither particularly decorative nor useful for tying objects. Since there is little skill involved in Western knotting, any outstanding example that is produced must have a unique design and an intricate blend of colors and materials.