Читать книгу God Is Not a Boy’s Name - Lyn Brakeman - Страница 8

Chapter 3 It Was a Very Good Year—for Cookies

ОглавлениеBy 1973, we lived in a four-bedroom colonial in North Canton, Connecticut. I relished my children’s blossoming lives with affection and some uncertainty. Were we settled? Were we normal yet?

Bill and my father had very different ways. Dad, through Mom, complained to me about Bill’s making promises they couldn’t keep—ping!—and Bill complained to me that my father was too damn organized—pong! Dad finally decided he couldn’t afford to continue and wrote Bill a letter. It was cowardly but it gave Bill some dignity space and opened the way for him to do what he’d always wanted: to start a business of his own.

“So this company I want to buy is in Stratford,” he told me.

“Stratford where?” I said.

“Connecticut, Lyn.”

“How far away is it?”

“Oh, maybe a hundred miles or so. I can commute till you find us a house down near there.”

My halfhearted house search bore the same results as any half-hearted activity. It failed. Bill got an apartment in Stratford, and commuted. I stayed home and watched my children grow. I wanted to grow, too. Bill’s energy went into his career, mine into the children. When Bill was home our “mutual affair” with alcohol protected us from ourselves and each other. We drank B & L scotch, a brand we affectionately dubbed “Bill & Lyn’s.”

My prayers had become dusty and dull but the local parish, Trinity in Collinsville, needed volunteers—for everything. Getting involved soothed my longings somewhat. What did I want? I was doing everything expected, I thought, yet I sat in my suburban kitchen baking chocolate chip cookies, a righteous activity that felt clumsy, and dreamed of a job with a paycheck. I reached for the necessary baking ingredients, one by one, from the refrigerator, pantry, and cupboard. In a dreamily narcissistic moment, I noticed my wrist—delicate, lovely, slim. It might, I imagined, have belonged to Princess Grace or a saint or mystic like Dame Julian of Norwich, of whom I’d dimly heard. Just gazing at my wrist caused me to realize—how long had it been, years? —that I scarcely noticed lovely things about myself.

The images of children who would delight in my cookies dashed across my mind’s eye. Bev, ten, a dark beauty who stalked me—her presence closer than my shadow, her gaze intense, seeming to question my right to exist. Jill, nine, also beautiful, with delicate features and an audacious mountain of curls to match her chutzpah. She had issued her declaration of independence at four—“There’s just not enough air in the world for me and Bev!” R. B., six, his face bright, irresistibly pleasing, plaintive, and lightly shadowed with anxious bewilderment. John, maturely handsome for a two-year-old, had a beguiling timidity that camouflaged the inner turmoil of his own miniature life in the shadow of three big siblings.

“Lynnie, the highest destiny for any woman is to be a good mother.” Mom’s fail-safe prescription for happiness sounded to me like a proscription. I had followed her rules but questioned myself mercilessly. Was I a good enough mother? Why didn’t I have orgasms? Very little made me angry. But I went to church. All was well.

All is not well at all. Something is wrong with me.

I had a secret and it wasn’t the old god-man. My secret was a broken heart. It was so broken that half of it fell out that day in my kitchen over cookies.

Why are you doing this?

An inaudible voice inquired, a polite, curious voice of simple candor and blinding clarity. It wasn’t my voice; it was, well, not from my mind. The only thing about this voice that was like me was that it asked a question. I scurried around the kitchen, ordered the utensil drawer, rearranged the canisters on the counter, and was about to go for the vacuum cleaner when I crumpled, sat down, put my head on the kitchen table, and sobbed.

How did you know, God?

The God who had listened to me as a child had found a voice. Jolted out of my spiritual torpor, I followed the cookie voice and waded into the deep turbulent waters of my self—looking for me, looking for God, looking for purpose, life, sex, and meaning beyond motherhood.

Before I embarked on an unknown path, I knew I should have a clean house. I grabbed the vacuum as if to throttle it and buzzed it around. When you’re making a decision you know will go against everything your mother, the church, and the world has set up for you, things get messy. In fact, when you listen to God from your soul’s depths, plan on dissonance. I was scared alive.

I seized life, grabbed for it, slashed wildly at what felt like a large thick oxygen-depriving plastic bag all round me. I rushed from Eden’s safety, apple in hand. This path of disobedience felt obedient to me, “meet and right” as the liturgical prayer said. One of the first things I did was to have an affair with a man, a flirty fling that upped my aliveness. It might not have been God’s will, but it was mine. Who can ever know what God’s will is, anyway? All I knew was that God had asked me a good question.

My next action was to enter bioenergetic therapy. That was just after I’d smashed the small aqua sugar bowl, that went with the aqua-and-white set of everyday dishes, which didn’t go with the two-tone persimmon-and-copper kitchen, onto the kitchen table. It shattered into more pieces than Humpty Dumpty. Sugar mixed with chunks and chips of cheap porcelain fanned out over the table as four astonished faces, with spoons filled with Cheerios poised on the way to hungry mouths, looked up. This was not their mother. Silence as heavy as a dentist’s X-ray apron slapped down on us all. A couple of tears rolled down John’s cheeks and more than a couple down mine. Bev got up and began to pick the broken shards from the sugar. Jill went to fetch her Siamese cat, and R. B. helped Bev, and said, “It’s okay, Mom.”

“You’re getting in touch with your anger,” my new counselor said. He was handsome, bearded, and a Rev. named John. He explained bioenergetic therapy, the brainchild of Alexander Louwen, as body work with deep breathing based on the idea that all the emotions one has ever felt were stored in the muscles. Emotions seek release. Of course!

“You mean my muscles could mess up my happiness, make me smash sugar bowls and scare my kids?” I asked.

“Well, not your muscles exactly, but the unresolved feelings trapped in your muscles. We’ll take it slowly, and talk about everything,” John assured me.

“You’re seeing a psychiatrist, now?” my mother asked. “What ever for?”

“I feel fucked up inside,” I said.

“Lynnie, that’s just ridiculous,” she proclaimed.

I bought a pink leotard and joined a bioenergetics exercise group after I’d stored up my fear in some muscle or other. I followed the instructions with care when suddenly I noticed, out of the corner of my eye, a woman collapse, curl up, and begin to suck her thumb. I kept breathing vigorously and tried not to gawk, or panic.

“I’m not sucking my thumb,” I told John, but didn’t tell him I’d sucked my thumb till I was twelve.

“Don’t worry, Lyn,” he said. “I know this woman and she was returning to her early comfort zone. She won’t stay there. You get in touch slowly.”

What in God’s name would I be “in touch with” next? I grew to detest that concept, but John seemed trustworthy. Some people, I’d heard, worked in the nude or underwear, so the therapist could see the muscles. Would I do that? I lost weight in case. Backbending over a stool released a welter of sorrow hidden under my breastbone. In my original family I’d cried at Christmas when everyone else was happy trimming the tree. I’d cried because Dad wasn’t there or was drunk, which my mother called “tired”; I’d cried because I’d broken my mother’s happiness rule, I’d cried because I felt different and somehow wrong. In therapy I didn’t suck my thumb or talk about the old god-man in the theater, but my body again asserted itself against my will, this time for my good.

Act III was to turn into Brenda Starr, girl reporter. I became a stringer, paid by the column inch, writing for a regional newspaper. My first paycheck was frameable, but I spent it. My byline thrilled me: “Planning and Zoning Commission Labors Over Decision to Close Town Dump” by Lyn Brakeman. Town meetings bored me stiff until I got home, poured myself a scotch, sat down at the dining room table with my typewriter, and wrote as many inches as I could, trying to infuse drama into tedium. My mother and my children did more babysitting than was good for any of them, a fact for which I remain grateful—and slightly guilty.

The Episcopal Church was as astir with change as I was. Right after my kitchen epiphany the church voted against a resolution to make it possible for women to be ordained priests. As a result, many women and some men restarted the life of the church, in ways about as untidy as mine. Women were raising hell, for the sake of heaven. Rules more ancient and entrenched than my, or even my mother’s, ideas of propriety, would be broken to force the church out of its torpor. If it couldn’t be done through proper channels, then it would be done outside canon law, outside God’s law too, some thought. Women took independent action and invaded the priestly caste. Would the church repent? Would I?

The Episcopal Church and I began our midlife crises together.

Free, wild, and frightened, I sat in the pew at my parish church and started to wrestle hard with my faith. What, besides God, did I believe in? I stared at the altar meal, my under-the-table meal, seeing it again as if for the first time—this time in a church that was willing to wrestle hard with women.

In the same year the church voted women’s ordination out, they voted that lay people (not just male ones) could be chalice bearers. Women were also permitted to read the Sunday Bible readings, and serve on parish vestries. I signed up for everything.

Being a chalice bearer required serious physical discipline just to hold the chalice steady for sips without emptying it down some woman’s cleavage while she knelt, her pious head bowed and the brim of her large hat making her lips un-locatable. It took more skill, in fact, than to scoot wee wafers into cupped fists as the priests did. Feeling a little like one of the Great Wallendas, I donned a black cassock and a long white-winged surplice over it. Such a pinafore! Thus I began a ministry inside the altar rail of God’s dining room table. I gripped that chalice for dear life.

Most astonishing among the expansive changes the church was enacting, was the new wording of the catechism defining ministry. The “ministers of the church” were formerly defined as “bishops, priests, and deacons”—the ordained. Now, the ministers of the church were “lay persons, bishops, priests, and deacons”—hierarchy radically reordered on paper. It meant that baptism, not ordination, made a person a “minister,” a status prophesied by a T-shirt slogan of the women’s ordination campaign: “Ordain Women or Stop Baptizing Them!”

The Episcopal Church prided itself on its changelessness—a characteristic it ostensibly shared with God. But now, many parts of its touted tradition were becoming unrecognizable: prayers, hymns, the definition of “minister.” Would the gender of clergy follow? Would the final staple of the Episcopal security system fall away? The pace of change was so swift that many good folks felt the wind knocked out of their souls. They often sought safety and comfort in resistance. Though many felt qualms about women at the helm, at heart they needed a reassuring mother.

The Eucharist, already rich in sacramental beauty and a reenactment of my childhood spirituality, became charged with new meaning for me. I’d recognized divine womanliness in the preparation and serving of this meal, but now saw that God fed people with her [sic] own body and blood. How much more intimate and nourishing could you get? The holy blood of Christ was less like martyrs’ blood or blood spilled by young men in wars, and more like the blood of life spilled by women for fertility. Maybe the patriarchal church had the divine gender wrong?

I kept my ideas to myself, but I began to wonder if this meal was a very different kind of sacrifice than the one proclaimed in the prayers of consecration week after week: We remember his death, we remember his death—his bloody, awful death. What about Jesus’ life? Did Jesus die for me? I had no answers that worked, and I felt crazy-confused, so I stopped thinking. Still, I couldn’t help but wonder if I would die for my children. Likely I would, but I knew for sure I had bled to give them life, and that this Eucharist had more to do with life than death—just as it had for me when I’d invented it under the table.

Next, I began to see Eucharist as a meal of justice: everyone was welcome, everyone got food, everyone got the same, not too little, not too much. One Sunday I sat and watched as everyone streamed up the aisle to kneel side by side at the altar rail, rubbing shoulders and extending their hands to receive their just portion of holy food. It wasn’t a dole. It seemed a miracle, because many of these same people had been quarreling vigorously all week about the rector’s latest decision, his tenure and sermons, the hymn choices, on and on. The Eucharist brought justice and with it peace—until Monday.

The church needed to be like its meal. Women weren’t getting justice. We should be behind altars, not just lecterns, preaching in pulpits, not just making announcements from the pew, distributing bread, not just wine. Caught up in the whirlwind of this transformative era and fed by the Eucharist, my spirit soared with feminist visions. For me the ordination of women was less about baptismal rights and more about sacramental justice: all sacraments, including the sacrament of ordination, should be open to all people. There was precedent for this in early church history, though I hoped there would be no bloodied martyrs this time. Jesus’ blood was enough, and, by this time, I was sure bloodshed of any kind was not ordained by God. I was equally sure that there was something we should do to help besides bleed. The church which I’d thought was, well, just spiritual, was about to be shaken. I wanted to be passively passionate and stand on the sidelines, but political action, which made me dizzy, was unavoidable.

In 1974 a group of eleven women were ordained priests outside of canon law in Philadelphia, a headline-making scandal. By 1975 four more women were “illegally” ordained in Washington, D.C. Through this movement, well organized and lobbied, women began to hold the church accountable more forcefully than ever. Outside the church too, women were holding society accountable. Amazing reversals were happening. My own state elected Ella Grasso as its first woman governor.

Many people reacted to the newly ordained women priests with verbal venom and hatred. The Washington ordinations nearly didn’t happen because of a bomb scare. Bomb-sniffing dogs were brought in before the service began. The Rev. Lee McGee, one of the Washington ordinands, later told me she’d imagined being in the sanctuary before the ordination service quietly praying for her new vocation. “I never thought I’d be praying for my life,” she said. To get ordained a woman priest had become a justification for mass murder? We could all be blown up! Was this only the lunatic fringe, or were women truly hated?

The courageous women who pioneered this movement had help from bishops who provided support and ordained them. The bishops were retired but still had authority to perform sacramental acts. Hence, the “rogue” ordinations were sacramentally legitimate, yet politically “illegal,” occurring before the assembled church officially voted to change the canon law. The “mind of the church”—a phrase conveniently used to postpone action forever—was not yet settled, and women were the disrupters. I couldn’t imagine myself going out on such a limb and risking alienation from something as big and powerful as Mother Church, to say nothing of the God people called “Father.”

A chilling quote was running around the grapevine of wrath. Carter Heyward, one of the Philadelphia Eleven priests, had received a vile letter after her ordination: “Go to hell, buck teeth! Someone ought to kill you. You’re filthy.” By now I’d read Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique and was a newly minted feminist who believed that the personal was political, and that the most offensive slurs were comments about a woman’s body and looks. How ironic, since women continued to devote so much time, money, and energy to self-beautification, in order to attract positive male attention. How many unnecessary diets had I tried? Thank God I’d already had braces.

The God I’d met in my childhood book and under the table was a God who shone favor on girls, and listened to me. My spirituality was intimately linked to my gender. I was one of three daughters in a family; my first school was founded and headed by a woman; all my teachers were women and all my classmates were girls. The patriarchal church and world in which I lived was crumbling, but my theological foundations held as I wondered how God felt about such desecration of women priests, such vehement rejection of half of His image, yet everyone I asked admitted God had no gender. Some people shouted out that what it said in Genesis about God’s image being created both male and female didn’t count, because it was in the Old Testament. In my mind, He placed God into one of those genders. Oh yes, but He really meant both, we all knew. Perhaps it was then that I began to think of God’s putative non-gender in a serious way, and to cringe about the obvious fact that while the heavens proclaimed the glory of God, all the damn English pronouns quietly and consistently proclaimed the infallible masculinity of God. It made me angry.

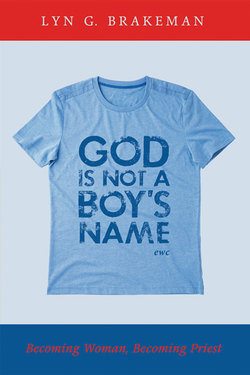

Ironically, the church’s inexorably male God language was so incongruent with the God I’d experienced that becoming a woman priest actually looked like the most congruent action to take. Should I reposition my Ritz-cracker “eucharist” from under the table to where it belonged—on top of the table, an altar where I would preside? Was anger a proper stimulus for a holy vocation? Yes. Anger had motivated me as a child and led me to God. Anger was behind the cries of women for justice, the moves to get ordained before the official vote to ordain, and on their T-shirts. I loved the one that read “God Is Not a Boy’s Name.” I thought of buying it but didn’t.

I wasn’t ready to be good yet. I felt like a woman in heat, howling inside like a cat. I lost more weight. I loved feeling hot and joyfully out of control and kept the moral incompatibility of my sexual fantasies and my lofty religious aspirations safely in the inanimate pages of a journal. Hungry for both sexual and sacramental intimacy, I tried but couldn’t separate these two urgings. Both drove me onward, and both felt inevitable. Hearing nothing from God and, frankly, not praying for restraint, I flirted ruthlessly with the sheer joy of life itself, with men wherever I encountered them, while at the same time dreaming of presiding at the Eucharist.

My therapist cheered my growth spurt and made no judgments, so I fell in love with him, to no avail. Vocational thoughts intruded in strange but recognizable ways. Motherhood, I told myself, was like priesthood. For over ten years I’d preached, taught, celebrated, fed, bathed, and blessed four young lives. I dreamed of going to seminary.

The blond parish rector, one of my flirtees, said one day: “You’re attracted to the things of the altar. Have you ever thought of being a priest?”

“No.” I lied.

Did this rector, named Steve, know what was inside me? I grew up trying to escape mother’s eagle eye and trusting only God to see through me, but this man’s spiritual eyesight caught me off guard. I laughed at him, reminding him that the mind of the church wasn’t settled.

“It will be,” he said.

“I have to become a woman before I can become a woman priest. I don’t feel ready and seminary is expensive.”

“Just a thought.” He shrugged and smiled. “Forget it.”

His comment was like telling a jury to disregard some crucial piece of evidence. I could not forget it.

Most people thought that women’s ordination would be approved at the 1976 General Convention. A revised edition of the Book of Common Prayer was in the works, as was a hymnal revision. I hoped the committees would make gender language more inclusive, and that they’d excise “Onward Christian Soldiers” from the hymnal—until a woman told me that as a young child regularly abused by her mother, she’d marched around carrying a broomstick cross, a little soldier singing for Jesus. “It gave me courage,” she said.

I wanted courage. God had asked me a question, and so had the rector of my parish.

“Were you serious about my being a priest?” I asked him.

“Mmmhmm.” He looked up from his desk and smiled all his charm my way.

“What would it take?” I asked.

I tried to concentrate on the details of the ordination process he explained, but his hair got in the way, a shock of blond hair that kept tumbling down onto his forehead. Fascinated, I watched him toss it back in place.

“You first have to become a postulant, as soon as the church votes, and it will. That means the bishop and his committees discern a call to priesthood in you and deem you fit to go to seminary. Lyn, are you listening?”

“Sure.”

“Well, what do you think?

“I think I’m scared the committee will ask me too many questions about my personal life.”

(I also think I could be falling in love with you.)

“Don’t worry. Pray about it and let me know. You’d be a good priest.”

(Would I be a good lover?)

I didn’t pray. I called Yale Divinity School and made an appointment for an interview and a visit. Just to see. Just in case. My father had graduated from Yale University in 1933. The idea of being a Yalie enticed me. Commuting was feasible. My children were growing up. What if . . . ?

The Yale Divinity School campus is rectangular. Marquand Chapel stands on a rise at the center, surveying the campus from on high and calling faithful worshipers into its bosom of praise. Red brick, white trim, a parade of steps up either side of the entrance to the simple white door, a clock tower with a cross on top—nothing like most Episcopal churches built of stone and with a steeple. It startled me at first. It looked like the Brick Presbyterian Church of my childhood. I was home.

Before I went to my appointment, I entered the chapel’s open doors and sat in a white pew. Wordless for once, I listened to my heart speak— thumpety thump—into the silence. God bless me, I said again and again and signed myself with a cross—head, genitals, right breast, left breast—a very full-bodied, un-Protestant thing to do, but an action that solicited God’s help to align conflicting forces within. I simply whispered, “God, let me come here.”