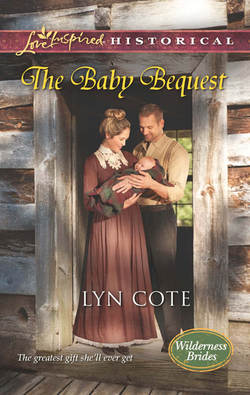

Читать книгу The Baby Bequest - Lyn Cote, Lyn Cote - Страница 13

ОглавлениеChapter Five

The next morning, Kurt waited, hunched forward on the last bench at the rear of the schoolroom where Sunday services were also held. When would Miss Thurston appear with the baby? He sat between a surly Gunther and an eager Johann, hoping neither his inner turmoil nor his eagerness to see her were evident.

A warm morning meant that the doors and windows had been opened wide, letting in a few lazy flies. Men, women and children, seated with their families, filled the benches. Ostensibly Kurt had come to worship with the rest of the good people of Pepin. But he knew he and his brother and his nephew did not look or feel like a family in the way that the rest of those gathered today did. Their family had been fractured by his father’s awful choices. Gloom settled on Kurt; he pushed it down, shied from it.

Wearing a black suit, Noah Whitmore, the preacher, stood by the teacher’s desk at the front. But Kurt knew that more than worship would take place here today. The foundling child would not be taken lightly. His stomach quivered, nearly making him nauseated, and he couldn’t stop turning his hat brim in his hands. He was nervous—for her.

He’d had no luck making the schoolteacher see sense last night. He didn’t want to see the fine woman defeated, but to his way of thinking, she didn’t have a hope. What would everyone say when they saw the baby? When they heard Miss Thurston declare she intended to keep him?

As if she’d heard his questions, the schoolteacher stepped from her quarters through the inner door, entering the crowded, buzzing schoolroom. With a polite smile, she called, “Good morning!” And then she paused near Noah, facing everyone with the baby in her arms, back straight, almost defiant.

As if hooked by the same fishing line, every face swung to gaze at her and then downward to the small baby, wrapped in the tattered blanket in her arms. Gasps, followed by stunned silence, met her greeting. Kurt had to give the lady her due. She had courage. Her eyes flashed with challenge, and Kurt could not help but notice that she looked beautiful in her very fine dress of deep brown.

She cleared her throat. “Something quite unusual happened last night. This baby was left on my doorstep.”

In spite of his unsettled stomach, Kurt hid a spontaneous smile. Her tone was dignified, and when a wildfire of chatter whipped through the room, she did not flinch. Kurt could not turn his gaze from her elegant face. She blushed now, no doubt because of the attention she drew.

Recovering first from surprise, Noah cleared his throat. “Was a note left with the child?”

Everyone quieted and fixed their stares on Ellen again.

“No, the child came without any identification.”

“Is it a boy or a girl?” a man Kurt didn’t know asked.

“How old is he?” Martin Steward asked. His wife, Ophelia, started to rise, but Martin gently urged her to remain seated. Would Miss Thurston’s family support her in her desire to keep the child?

“The infant is around a month old, Mrs. Ashford thought,” the schoolteacher said. “He is a boy, and I’ve named him William.” At that moment, William yawned very loudly. A few chuckled at the sound.

Mr. and Mrs. Ashford, in their Sunday best, hurried inside with Amanda between them. “We’re sorry to be late,” Mr. Ashford said, taking off his hat.

“But we lost so much sleep helping Miss Thurston with the foundling last night,” Mrs. Ashford announced, proclaiming herself as an important player in this mystery. “We overslept.”

Kurt watched them squeeze onto the bench in front of him, though plenty of space remained open beside Johann. The simple act scraped his tattered pride. When he noted their daughter steal a quick glance at Gunther, his tension tightened another turn. The Ashfords would never let Gunther court their daughter. That was as ridiculous as if he decided to pursue Miss Thurston himself.

This realization choked him and he tried to dismiss it.

Ellen nodded toward the rear of the room. “Yes, thank you, Mrs. Ashford. I’ll need more of that Horlick’s infant powder today. So far he seems to be tolerating it well.”

Mrs. Ashford perched on the bench, her chin lifted knowingly.

“Well, what are we going to do about this, Noah?” a tall, young deacon named Gordy Osbourne asked, rising. Many nodded their agreement with the inquiry.

Kurt braced himself. Now unrelenting reality regarding her station in life would beat against Miss Thurston.

Noah looked troubled. “Is the child healthy, Miss Thurston?”

Before Ellen could respond, Mrs. Ashford piped up, “He appears healthy, but is disfigured by a birthmark on his head.”

“He has what’s called a port-wine stain on his forehead,” Miss Thurston corrected, “but his hair will cover it as he grows.” The lady sent a stern glance at the storekeeper’s wife and held the child closer.

Why didn’t she see that he’d been right? No one was going to let her keep this child. He realized he’d been mangling his hat brim and eased his grip.

“Unless the mark grows, too, and spreads,” Mrs. Ashford said, sounding dour.

“I don’t think that has anything to do with the baby’s health,” Noah commented. “A birthmark will not hurt the child.”

“Maybe that’s why somebody abandoned him at the teacher’s door,” Osbourne’s wife, Nan, spoke up. “Some people don’t want a child with that kind of mark.”

“Unfortunately you may be right,” Noah said. “But the real question is, does anyone here know of any woman in this area who was expecting a child in the past month?”

Kurt admired Noah’s ability to lead the gathering. Was it because he was the preacher, or had he done something in the past to gain this position? In Europe, leadership would have to do with family standing and connections, but here, that didn’t seem to matter. No town mayor or lord would make this decision. Noah Whitmore had thrown the question open for discussion—even women had spoken. This way of doing things felt odd but good to Kurt.

Noah’s wife, Sunny, rose. “I think I can say that no woman I know in this whole area was expecting a baby last month.”

“Perhaps someone from a boat left him at the schoolhouse,” Miss Thurston said, “because it is the only public building in Pepin, and a little away from town. They would have been less likely to be observed leaving the child.”

The congregation appeared to chew on this. Kurt stared at Miss Thurston, remembering her initial hesitation to pick up the child and her mention of a baby brother who’d died. She had known loss, too. Wealth and position could not prevent mortality and mourning. He forced his tight lungs to draw in air.

“Well, we will need a temporary home for the child—” Noah began.

“I will keep the child,” Miss Thurston said, and then walked toward the benches as if the matter were settled.

Her announcement met with an instant explosion of disapproval, just as Kurt had predicted.

One woman rose. “You can’t keep a baby. You’re not married.” Her tone was horrified.

Ellen halted. “I don’t know what that has to do with my ability to care for a child. I’ve cared for children in the past.”

“But you’re the schoolmarm!” one man exclaimed. General and loud agreement followed.

Kurt didn’t listen much to the crowd, but watched for the reactions of the young pastor. And Miss Thurston, who’d paused near the front row, half-turned toward the preacher, too.

The pastor’s wife silenced the uproar merely by rising. “There is an orphanage in Illinois run by a daughter of our friends, the Gabriels. We might send the child there.”

Murmurs of agreement began.

Miss Thurston swung to face everyone again. “I think that is a precipitate suggestion. What if the child’s mother changes her mind? I don’t think it’s uncommon for a woman to become low in spirits soon after a birth.”

A few women nodded in agreement.

“What if this woman suffered this low mood and was in unfortunate circumstances? After realizing what she’s done, she might return to reclaim the child. I think it’s best we wait upon events.”

A man in the rear snorted and muttered loud enough for all to hear, “It’s probably somebody’s unwanted, baseborn child.”

Noah stiffened. “I think we need to remember why we are gathered here.”

That shut everyone up, suiting Kurt’s idea of propriety. A child’s life was not a subject for derision.

Noah gazed out at the unhappy congregation. “Miss Thurston is right, I think. A child’s future depends on our making the right decision. This is something we need to pray about so we do what God wants. One thing is certain—no woman gives up her child lightly. Someone has trusted us with their own blood and we must not act rashly.”

His words eased some of the tension from the room, another sign of Noah’s leadership. Again, Kurt wondered about the preacher’s past and how he’d come to be so respected here. Kurt’s family had been respected in their village, but had lost that over his father’s many sins.

“But who’s going to take care of the foundling in the meantime?” Mrs. Ashford asked.

“I will,” Ellen declared. “He was left on my doorstep.”

The storekeeper’s wife started, “But you’ll be teaching—”

“I’m sure we can find someone who will care for the child while Miss Thurston carries out her teaching duties,” Noah said, taking charge of the room. “That’s something else we will pray about.”

Noah raised his hands and bowed his head and began praying, effectively ending the discussion. Kurt lowered his head, too, praying that Miss Thurston wouldn’t be hurt too badly when the child was taken from her. Because he was certain that that was exactly what was going to happen, one way or the other.

* * *

Ellen’s face ached with the smile she’d kept in place all morning during the church service. She wished everyone would just go home and leave her alone. But the congregation lingered around the schoolhouse, around her.

Everyone wanted a good look at William and an opportunity to express their opinion of wicked people who abandoned babies. They also lauded her desire to care for the child—even if she were a schoolmarm, a woman was a woman, after all. Most voiced sympathetic-sounding, nonetheless irritating comments about William’s birthmark. Noah and Sunny had helped her but underneath all the general sentiment still held that she shouldn’t, wouldn’t, be allowed to keep William. Ellen was nearing the end of her frayed rope.

Then Martin came to her rescue. “Cousin Ellen, you’re coming home with us for Sunday dinner as planned.” He smiled at everyone as he piloted her toward their wagon. When Martin helped her up onto the bench, she noted Mr. Lang and his family, who had ridden to church with the Stewards, sat in the wagon bed at the rear. This man had predicted how the community would react all too accurately. But he didn’t look triumphant in the slightest, and for that, she was grateful. He nodded to her and gave her a slight smile that seemed to have some message she couldn’t quite read.

As the wagon rocked along the track into the shelter of the forest, Ellen breathed out a long, pent-up sigh. She glanced at her cousin sitting beside her. “Ophelia...” She fell silent; she simply didn’t have the words to go on.

Ophelia leaned against Ellen’s shoulder as if in comfort. “I can’t believe this happened.”

Ellen rested her head against the top of Ophelia’s white bonnet, murmuring, “I’m so glad you’re here.”

“The Whitmores are coming over after dinner so we can discuss this,” Martin said. “We need to decide what to do with this child.”

Ellen snapped up straight. “It has already been decided. William will stay with me.”

“You can’t mean you really want to keep this baby?” Ophelia said, sounding shocked. “I don’t know how I’d take care of our little one alone.”

Her cousin’s stunned tone wounded Ellen, stopping her from responding.

“Ja—yes, she does,” Mr. Lang said as the wagon navigated a deep rut. “I told her last night that they will not let her.”

Mr. Lang’s words wounded more than all the rest. He’d been there last night, he’d experienced discovering this child with her. Why wouldn’t he take her side in this matter?

She brushed the opposition aside. It didn’t matter why he wouldn’t support her—it didn’t matter why any of them wouldn’t support her. She wasn’t like other women. She had goals, and now she’d added one more. If she were a weak woman, she wouldn’t be here to begin with—she would be living at home under her sister-in-law’s snide thumb. But she had struck out to make a life of her own, and that was exactly what she planned to do.

Those who opposed her would not win. All she had to do was come up with a convincing argument to keep this child—and her job. And frankly, she reminded herself, Mr. Kurt Lang’s opinion in this matter—in all matters—was irrelevant to her.

* * *

Later, in the early dusk, Kurt walked into the Steward’s clearing for the second time that day. Ever since the Stewards had dropped them off after church, he’d been worrying—about William, about Gunther, about Miss Thurston.

“Kurt, what brings you here?” called Martin, who was hitching the pony to his two-wheeled cart.

“Is Miss Thurston here still?” The fact he couldn’t easily pronounce the “Th” at the beginning of her name caused him to flush with embarrassment. He tried to cast his feelings aside. He had come to talk with Miss Thurston face-to-face over Gunther’s schooling. Altogether, the issue had left a sour taste in his mouth. But a decision must be made—Gunther’s playing hooky had forced his hand.

“She’s about done feeding the baby and then I’m taking her home,” Martin said as he finished the hitching.

“I have come to offer to escort the lady home.”

Martin turned to Kurt. “Oh?”

The embarrassment he’d just pushed away returned. Kurt tried to ignore his burning face. Did Martin think he was interested in Miss Thurston? “I wish to speak to her about my brother, Gunther, before school starts again tomorrow.”

At that moment, the lady herself stepped out of the cabin with William in her arms. She noticed him and stopped. “Mr. Lang.”

Sweeping off his hat, Kurt felt that by now his flaming face must be as red as a beetroot. “I come to take you home, Miss Thurston. And perhaps we talk about Gunther?”

She smiled then and walked toward the cart. “Yes, I want to discuss that matter with you.”

They said their farewells to the Stewards, and soon Ellen sat beside him on the seat of the small cart, holding the baby whose eyelids kept drooping only to pop open again, evidently fighting sleep. Kurt turned the pony and they began the trip to town, heading toward the golden and pink sunset. Crickets sang, filling his ears. Beside him, Miss Ellen Thurston held herself up as a lady should. Only last night had he seen her usual refined composure slip. Finding the infant had shaken her. Did it have something to do with the little brother she’d mentioned?

Kurt chewed his lower lip, trying to figure out how to begin the conversation about his brother. “I still don’t agree with what you have said about Gunther,” he grumbled at last.

“But yet you are here, talking to me” was all she replied.

A sound of frustration escaped his lips. “Gunther...” He didn’t know what he wanted to say, or could say. He would never speak about the real cause of Gunther’s rebelliousness. He would never want Miss Thurston to know the extent of his family’s shame. His father’s gambling had been enough to wound them all. What had driven him even further to such a disgraceful end?

Kurt struggled with himself, with what to do about his brother. Gunther needed to face life and go on, despite what had happened. Would his giving in weaken his brother more?

“Your brother is at a difficult age—not a boy, not fully a man,” she said.

If that were the only problem, Kurt would count himself fortunate. So much more had wounded his brother, and at a tender age. A woodpecker pounded a hollow tree nearby, an empty, lonely sound.

“Gunther and Johann are all I have left.” He hadn’t planned to say that, and shame shuddered deep inside his chest.

“I know how you feel.”

No, she didn’t, but he wouldn’t correct her. “Do you still think to teach Gunther in the evenings?”

“Yes. As you know, you can send him to school, but you cannot make him learn if he’s shut his mind to it. Private lessons would be best.”

Kurt chewed on this bitter pill and then swallowed it. “He will have the lessons, then.”

“Will you be able to help him with his studies on the evenings when I am not working with him?”

“I will.”

“Then bring him after supper on Tuesday.” Miss Thurston looked down at the child in her arms and smiled so sweetly—Kurt could tell just from her expression that she had a tender heart. Something about her smile affected him deeply and he had to look away.

She glanced up at him and asked, “Have you told Gunther about this?”

“I tell him soon,” he said.

“Good.” She sounded relieved.

He, however, was anything but relieved. His fears for Gunther clamored within. They had come to this new country for a new start. He wanted Gunther to make the most of this, not end up like their father had.

They reached the downward stretch onto the flat of the riverside. He directed the pony cart onto the trail to the school. Again, he was bringing her home in Martin’s cart and again someone was waiting on her doorstep. This time a woman rose to greet them. What now?

Kurt helped Miss Thurston down. She moved so gracefully as a shaft of sunset shone through the trees, gilding her hair. He forced himself not to stop and enjoy the sight. Instead, he accompanied her to greet the woman.

“Good evening,” Miss Thurston said, cradling the sleeping baby in her arms.

The other woman replied, “I am Mrs. Brawley. My husband and I are homesteading just north of town.”

“Yes?” Miss Thurston encouraged the woman.

“I have one child and I heard the preacher say this morning that you needed someone to care for the baby.” The woman gazed at the child, sleeping in the lady’s arms.

“I take it that you may be interested in doing that?” the schoolteacher asked.

“Yes, miss. I could take care of two as well as one.”

“May I visit your home tomorrow after supper and discuss it then?”

“Yes, yes, please come.” The woman gave directions to her homestead, which lay about a mile and a half north of town. They bid her good-night and she hurried away in the lowering light of day.

“Well, I hope this will solve the problem of William’s care during the schooldays.”

Her single-mindedness scraped Kurt’s calm veneer. “You think still they will let you keep the child?”

She had mounted the step and now turned toward him. “Perhaps you are one of those who think a woman who does not wish to marry cannot love a child, and is unnatural. That is the common wisdom.”

Her cold words, especially the final ones, startled him. “No. That is foolish.”

Her face softened. “Thank you, Mr. Lang.”

He tried to figure out why anybody would think that. Then her words played again in his head. “You do not wish to marry?”

“No, I don’t wish to marry.”

Her attitude left him dumbfounded. “I thought every woman wished to marry.”

She shook her head, one corner of her mouth lifting. “No, not every woman. Good night, Mr. Lang. I’ll see you Tuesday evening.”

“Guten nacht,” he said, lapsing into German without meaning to. He turned the pony cart around and headed toward the Stewards’ to return it. Thoughts about Miss Thurston and William chased each other around in his mind. Very simply, he hated the thought of seeing her disappointed. What if she became more deeply attached to William and the town forced her to give the child away in the end?

Why wouldn’t she face the fact that the town would not let her keep William? He wouldn’t press her about this, but in fact, the town shouldn’t let her keep him. The question wasn’t whether Miss Thurston was capable of rearing the child. But didn’t he know that raising a child alone was difficult, lonely, worrying? Didn’t he know it better than anyone here?