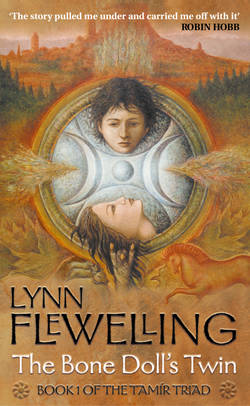

Читать книгу The Bone Doll’s Twin - Lynn Flewelling - Страница 17

CHAPTER EIGHT

ОглавлениеSince that strange Sakor’s Day morning, his mother ceased to be a ghost in her own household.

Her first acts were to dismiss Sarilla and then dispatch Mynir to the town to find a suitable replacement. He returned the following day with a quiet, good-natured widow named Tyra who became her serving maid.

Sarilla’s dismissal frightened Tobin. He hadn’t cared much for the girl, but she’d been a part of the household for as long as he could remember. His mother’s dislike of Nari was no secret, and he was terrified that she might send the nurse away, too. But Nari stayed and cared for him as she always had, without any interference.

His mother came downstairs nearly every morning now, properly dressed with her shining black hair braided or combed in a smooth veil over her shoulders. She even wore some scent that smelled like spring flowers in the meadow. She still spent much of the day sewing dolls by the fire in her bedchamber, but she took time now to look over the accounts with Mynir and came out to the kitchen yard with Cook to meet the farmers and peddlers who called. Tobin came along, too, and was surprised to hear of famine and disease striking in nearby towns. Before now, those were things that always happened far away.

Still, as bright as she was during the day, as soon as the afternoon shadows began to lengthen the light seemed to go out of her, too, and she’d retreat upstairs to the forbidden third floor. This saddened Tobin at first, but he was never tempted to follow and the next morning she would reappear, smiling again.

The demon seemed to come and go with the daylight, too, but it was most active in the dark.

The teeth marks it left on Tobin’s cheek soon healed and faded, but his terror of it did not. Lying in bed beside Nari each night, Tobin could not rid himself of the image of a wizened black form lurking in the shadows, reaching out with taloned fingers to pinch and pull, its sharp teeth bared to bite again. He kept the covers pulled up to his eyes and learned to drink nothing after supper, so that he wouldn’t have to get up in the dark to use the chamber pot.

The fragile peace with his mother held, and a few weeks later Tobin walked into his toy room to find her waiting for him at a new table.

‘For our lessons,’ his mother explained, waving him to the other chair.

Tobin’s heart sank as he saw the parchments and writing materials. ‘Father tried to teach me,’ he said. ‘I couldn’t learn.’

A small frown creased her forehead at the mention of his father, but it quickly passed. Dipping a quill into the inkpot, she held it out to him. ‘Let’s try again, shall we? Perhaps I’ll be a better teacher.’

Still dubious, Tobin took it and tried to write his name, the only word he knew. She watched him struggle for a few moments, then gently took back the quill.

Tobin sat very still, wondering if there would be an outburst of some sort. Instead, she rose and went to the windowsill, where a row of his little wax and wooden carvings stood in a row. Picking up a fox, she looked back at him. ‘You made these, didn’t you?’

Tobin nodded.

She examined each of the others: the hawk, the bear, the eagle, a running horse, and the attempt he’d made at modelling Tharin holding a wood splinter sword.

‘Those aren’t my best ones,’ he told her shyly. ‘I give them away.’

‘To whom?’

He shrugged. ‘Everyone.’ The servants and soldiers had always praised his work and even asked for particular animals. Manies had wanted an otter and Laris a bear. Koni liked birds; in return for an eagle he’d given Tobin one of his sharp little knives and found him soft bits of wood that were easy to shape.

As much as Tobin loved pleasing them all, he always saved his best carvings for his father and Tharin. It had never occurred to him to give one to his mother. He wondered if her feelings were hurt.

‘Would you like to have that one?’ he asked, pointing to the fox she still held.

She bowed slightly, smiling. ‘Why, thank you, my lord.’

Returning to her chair, she placed it on the table between them and handed him the quill. ‘Can you draw this for me?’

Tobin had never thought to draw anything when it was so easy to model them. He looked down at the blank parchment, flicking the feathered end of the quill against his chin. Pulling the shape of something from soft wax was easy; to make the same shape real this way was something else again. He imagined a vixen he’d seen in the meadow one morning and tried to draw a line that would capture the shape of her muzzle and the alert forward set of her ears as she’d hunted mice in the grass. He could see her as clearly as ever in his mind, but try as he might he couldn’t make the pen behave. The crabbed scrawl it drew looked nothing like the fox. Throwing the quill down, he stared down at his ink-stained fingers, defeated again.

‘Never mind, love,’ his mother told him. ‘Your carvings are as good as any drawing. I was just curious. But let’s see if we can make your letters easier for you.’

Turning the sheet over, she wrote for a moment, then sanded the page and turned it around for Tobin to see. There, across the top, were three A’s, written very large. She dipped the pen and gave it to him, then rose to stand behind him. Covering his hand with hers, she guided it to trace the letters she’d drawn, showing him the proper strokes. They went over them several times, and when he tried it alone he found that his own scrawls had begun to resemble the letter he was attempting.

‘Look, Mama, I did it!’ he exclaimed.

‘It’s as I thought,’ she murmured as she drew out more practice letters for him. ‘I was just the same when I was your age.’

Tobin watched her as she worked, trying to imagine her as a young girl in braids who couldn’t write.

‘I made little sculptures, too, though not nearly as nice as yours,’ she went on, still writing. ‘Then my nurse taught me doll making. You’ve seen my dolls.’

Thinking of them made Tobin uncomfortable, but he didn’t want to seem rude by not answering. ‘They’re very pretty,’ he said. His gaze drifted to her doll, slumped in an ungainly heap on the chest beside them. She looked up and caught him staring at it. It was too late. She knew what he was looking at, maybe even what he was thinking.

Her face softened in a fond smile as she took the ugly doll onto her lap and arranged its misshapen limbs. ‘This is the best I ever made.’

‘But … well, how come it doesn’t have a face?’

‘Silly child, of course he has a face!’ She laughed, brushing her fingers across the blank oval of cloth. ‘The prettiest little face I’ve ever seen!’

For an instant her eyes were mad and wild again, like they had been in the tower. Tobin flinched as she leaned forward, but she simply dipped the pen again and went on writing.

‘I could shape anything with my hands, but I couldn’t write or read. My father – your grandfather, the Fifth Consort Tanaris – showed me how to teach my hand the shapes, just as I’m showing you now.’

‘I have a grandfather? Will I meet him someday?’

‘No, my dear, your grandmama poisoned him years ago,’ his mother said, busily writing. After a moment she turned the sheet to him. ‘Here now, a fresh row for you to trace.’

They spent the rest of the morning over the parchments. Once he was comfortable with tracing, she had him say the sounds each letter represented as he copied them. Over and over he traced and repeated, until by sheer rote he began to understand. By the time Nari brought midday meal up to them on a tray, he’d forgotten all about his grandfather’s curious fate.

From that day on, they spent part of each morning here as she worked with surprising patience to teach him the letters that had eluded him before. And little by little, he began to learn.

Duke Rhius stayed away the rest of the winter, fighting in Mycena beside the King. His letters were filled with descriptions of battles, written as lessons for Tobin. Sometimes he sent gifts with the letters, trophies from the battlefield: an enemy dagger with a serpent carved around the hilt, a silver ring, a sack of gaming stones, a tiny frog carved from amber. One messenger brought Tobin a dented helmet with a crest of purple horsehair.

Tobin lined the smaller treasures up on a shelf in the toy room, wondering what sort of men had owned them. He placed the helmet on the back of a cloak-draped chair and fought duels against it with his wooden sword. Sometimes he imagined himself fighting beside his father and the King. Other times, the chair soldier became his squire and together they led armies of their own.

Such games left him lonesome for his father, but he knew that one day he would fight beside him, just as his father had promised.

Through the last grey weeks of winter Tobin truly began to enjoy his mother’s company. At first they met in the hall after his morning ride with Mynir. Once or twice she even went with them and he was amazed at how well she sat her horse, riding astride with her long hair streaming free behind her like a black silk banner.

For all her improvement with him, however, her attitude towards the others of the household did not change. She spoke seldom to Mynir and almost never to Nari. The new woman, Tyra, saw to her needs and was kind to Tobin, too, until the demon pushed her down the stairs and she left without even saying goodbye. After that, they made do without a maid.

Most disappointing of all, however, was her continuing coldness towards his father. She never spoke of him, spurned any gifts he sent, and left the hall when Mynir read his letters by the hearth each night to Tobin. No one could tell him why she seemed to hate him so, and he didn’t dare ask his mother directly. All the same, Tobin began to hope. When his father came home and saw how improved she was, perhaps things might ease between them. She’d come to love him, after all. Lying in bed at night, he imagined the three of them riding the mountain trails together, all of them smiling.