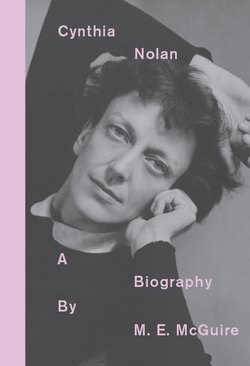

Читать книгу Cynthia Nolan - M. E. McGuire - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Drawing the Veil

‘Draw the veil’ was one of Cynthia Nolan’s favourite admonitions, with a variety of applications. It was a strategy she used to protect herself from unwanted attention as the artist’s wife, initially to shield her conservative family in Tasmania from the local opprobrium of a daughter marrying a modern artist, and over time to avoid the scrutiny of her elder brother in Melbourne. After one final interview at home in Sydney in 1950, she drew a veil over her previous life as Miss Cynthia Reed and her considerable achievements, traveller, young entrepreneur in art and design in Melbourne, psychiatric nurse qualifying during World War II, single mother and novelist. Her novels written during this time were Lucky Alphonse (1944) and Daddy Sowed a Wind (1947). Their originality lies in her exploration of the female psyche in a climate of fascism. Her heroines are counter images of each other: Alphonse, the lucky one, and Hyacinth, who chooses suicide.

As a child, Cynthia was nicknamed Bob, a name she kept for family and friends for many years. When she first lived in Sydney in 1934, she used Miss Liese Fels for the film career she was hoping for. Returning to Australia in 1941, she named herself Mrs Knut Hansen, to protect her unborn child from the stigma of illegitimacy. Once she married, she became simply Cynthia. Her last novel, A Bride for St Thomas (1970), opens as a young Australian, Mary Bates, a ‘girl with old bracken hair and smudged-in eyes’, sees herself reflected in a mirror:

… she was me. I only realised this when she straightened up and took her elbows off the table. How I wished my face was a secret rather than a confession.

Cynthia learnt how to appear inscrutable, at times unknowable. Her suicide in wintry London in 1976 was the ultimate drawn veil.

She and Sidney Nolan had been married for twenty-eight years. They were constant companions, their lives and work so intertwined as to be inseparable. Without her experience working with artists, galleries, journalists and audiences and her ability to win people over, Nolan’s ascendancy would have been less assured. He was, by contrast to outspoken Cynthia, a chameleon, changing to please the company he kept. (After the Ern Malley hoax, no-one was going to trick him out.)

Nolan’s career took off in Sydney in 1949, followed by more successful exhibitions before they moved permanently to England in 1953, where he would win public recognition. They moved out of the city to a house on the Thames in Deodar Road, Putney, five miles southwest of London.

In his obituary, ‘The Cynthia I Knew’, Patrick White wrote that Cynthia had been complicated: ‘Although capable of happiness in its most limpid forms, deeper down she was a tormented creature, having endured an unhappy childhood surrounded by … Tasmanian-Gothic gloom.’1

Cynthia began seeking psychiatric care in her twenties and would continue to do so until her last years. For the most part, she dealt with her own ‘oddities’ and found that work had its compensations. She wasn’t like Virginia Woolf, who took her own life because she couldn’t cope with another phase of hallucinations, nor the wives of T. S. Eliot and Kenneth Clark, who were incarcerated in mental hospitals. Her suicide has much in common with euthanasia. She was frail in health, often in severe back pain — the last time Patrick, Manoly and the Nolans went to an opera, Cynthia had to lie on the floor to listen.

This biography passes lightly over her last years, in favour of establishing her considerable achievements, which well warrant recognition. I never met Cynthia, but got to know her first through her travel books, then through her intimate letters to her brother and his wife in which she subjects her behaviour, moods, desires and beliefs to close analysis. At every opportunity in this reading of her life and death, she speaks for herself.

1 The Australian, 7 December 1976, p. 7.