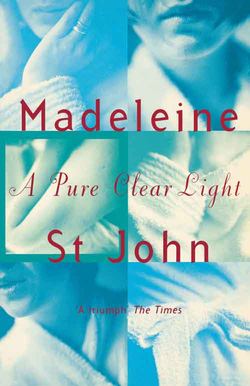

Читать книгу A Pure Clear Light - Madeleine John St. - Страница 8

4

ОглавлениеHail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee, said Flora under her breath, and the Virgin Mary (all lit up from inside, as if by an electric light bulb) inclined her head ever so slightly. She was ready to receive whatever further confidences Flora might have. What did you wish to say to me, my child? Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Yes, yes. And? Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death. Very good, Flora: I will pray for you. Ever-ready, ever-virgin mother of God – pray for my children! Certainly. And Simon, my husband. It shall be done.

Flora picked up the paring knife and went on with the dinner preparations. She didn’t sufficiently believe in God – believe? in God? what could this possibly, now, mean? – to pray to him, or Him, or, just conceivably, Her – but the Virgin was a tolerant sort of creature: nothing if not tolerant: look what she’d put up with already! so there was no difficulty about asking her to do the praying for one. That was what mothers were for. Hail Mary, full of grace, she began again; and the front door slammed shut and Simon came in. The light went out inside the Virgin Mary and she faded from view. ‘Oh, hello darling,’ said Flora; ‘how was your day?’

‘Pretty vile. What about you?’

‘Oh, fine, fine. My day was fine.’

‘Oh well. Have we got any gin?’

‘Could you just go and sort out the kids first – there’s an arbitration matter. I left it for you.’

‘Those bloody kids. Where are they?’

‘Upstairs. No, Janey’s in the sitting room. You’ll find them soon enough if you look. Go on.’

He went away, muttering, but came back looking pleased with himself. ‘I’ve sorted it,’ he said.

‘Good.’

‘I had to bribe them.’

‘Did it cost much?’

‘A fiver.’

‘No one could say we haven’t taught them the value of money.’

‘No, they could not. Where’s that gin?’

Holy Mary, Mother of God.

‘I was thinking, so long as you can’t come to France – is that really off, Simon? Definitely? – I was thinking, I might ask Lydia if she’d like to come with us.’

‘What?’

‘Lydia. You know, Faraday. Lydia Faraday.’

‘Yes, I know who you mean. Lydia Faraday. What on earth do you want to ask Lydia Faraday for?’

‘Well, why ever not? Poor Lydia.’

‘Poor hell.’

‘Simon!’

‘Well, for God’s sake.’

‘Anyway, what’s it to do with you? You won’t be there.’

‘Oh, Flora.’ Simon sprawled back in his armchair and clutched his head. ‘Honestly,’ he said. ‘Lydia.’

Flora, watching this performance, began to laugh.

‘What have you got against poor Lydia?’ she said. Simon let go of his head and sat up. He reached for the gin bottle and topped up his drink – Flora always made them too weak – and took a swallow.

‘In the first place,’ he said, ‘she isn’t poor. She’s probably got more than the rest of us put together. Jack was saying –’

‘Then he shouldn’t have been,’ said Flora severely. Jack Hunter, a solicitor, had done some work for Lydia a year or two back, when she had got into a tax muddle.

‘Don’t be priggish,’ said Simon. ‘The point is, Lydia likes to put it about that she’s on her uppers, but –’

‘That’s not true either,’ said Flora. ‘I never heard her putting it about that she was short of money.’

‘No, she doesn’t say so in so many words,’ said Simon. She’s not that obtuse. She just suggests it in a thousand tiny ways. I could practically throttle her sometimes. Who’s she trying to impress?’

‘Simon, what are you talking about?’ cried Flora, amidst her laughter. ‘Name me even one of these thousand tiny ways.’

‘Well, look at the way she dresses,’ said Simon, ‘for a start.’

‘Dresses?’

‘Yes, dresses.’

‘Fancy your noticing the way she dresses!’ Flora had stopped laughing, or even smiling. What could this mean?

Simon scented the danger and rushed to avert it. ‘I wouldn’t notice,’ he said, ‘if she didn’t simply demand one’s attention every time you see her. Oh God. Those bits and pieces.’

‘I always think Lydia looks very nice,’ said Flora, whose own taste ran to French jeans and plain white T-shirts, and things from the Harvey Nick’s sales for more formal occasions; ‘for a woman of her age.’

‘Miaow!’ cried Simon, and they both laughed. One thing which cemented their relationship was that gin always put them in a good humour; so generally they drank some every evening.

‘And that’s another thing,’ said Simon.

‘What is?’ said Flora.

‘Well, her age. I mean, Lydia: it was one thing when one first knew her; fair enough; loose cogs – you expect them when they’re in their twenties, early thirties. Missed the first bus, but there’ll still be a few more; but now, ten years or so later – well: precious few buses. Probably none. Probably missed the last one. And there she still is loose-cogging around the scene, just getting in the way – it’s embarrassing.’

Flora was appalled. ‘Well, really!’ she exclaimed. ‘How –’

‘And then she has to make a meal of it,’ said Simon, ‘with all those jumble-sale outfits. And that itty-bitty flat of hers. And she always wants a lift. She’s just so pointless.’

‘Mother of God,’ said Flora.

‘You what?’

‘Mother,’ said Flora. ‘Of God.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Honestly, Simon. If you could hear yourself. The cruelty. That poor woman. What has she ever done to you?’

Simon had been recalled, unexpectedly, to sobriety. He considered the question. ‘I dunno,’ he said. ‘She just depresses me.’

‘Ah,’ said Flora. ‘Yes. I see. Yes. Make me another drink will you? There’s just time for another before we eat.’ She watched while Simon made the drink. Lydia was sometimes a bit of a downer, that was a fact; but she couldn’t quite tell why. Oh, Mother of God: pray for us sinners.