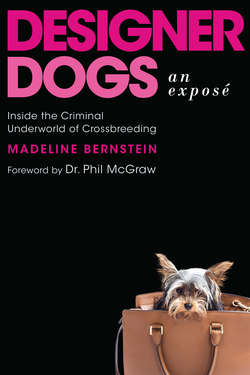

Читать книгу Designer Dogs: An Exposé - Madeline Bernstein - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

The Designer Dog: Name-Brand Purebreds and Custom-Designed Dogs

I thought that nature was enough, till human nature came.

—Emily Dickinson

There are two types of designer dogs: name-brand purebreds and custom-designed dogs. A name-brand purebred is a dog whose lineage can be verified and is sold with the assurance that he has no family history of “contamination” with a different breed. It’s widely believed that breeding dogs carefully over many generations, in a continuous cycle of purebred parents and purebred puppies, results in predictability in appearance and behavior—that is, they “breed true” and will look and act a certain way. When sold to a new owner, a name-brand purebred may come with a certification of purity from a recognized association, such as the American Kennel Club (AKC). A breeder may sell these dogs at an especially high price.

There are hierarchies in the world of name-brand purebreds that define the value of a dog. This value is determined by things such as the rarity of the breed; its success in dog shows; and the media attention it has attracted, usually because a dog of the breed has been in a popular television show or movie, or a celebrity owns and has been photographed with a dog of the breed. Almost everyone in the United States has heard of a German shepherd, but not an Azawakh, a long-legged hunting dog native to Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, that is rare and hard to acquire in the United States, traits that make them particularly valuable. The dalmatian is an example of a breed that became highly desirable after a film popularized it—101 Dalmations. The Chihuahua became increasingly in demand after starring in commercials for Taco Bell and films such as Beverly Hills Chihuahua and Legally Blonde, and becoming a popular dog for celebrities to own. Photographs of Paris Hilton and her Chihuahua Tinkerbell were a tabloid fixture throughout Hilton’s rise to fame. Presidential dog breeds are eternally popular. Demand for the Portuguese water dog skyrocketed after President Barack Obama and his family adopted two dogs of the breed, Sunny and Bo. Stars of the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show and the Crufts dog show have made other breeds, such as the standard poodle, boxer, Airedale terrier, and American and English cocker spaniels, valuable as well.

Included in the name-brand category are toy breeds. Toy breeds are a subset of an established breed that has been bred down in size to create a lapdog version of the breed. As in the case of larger purebreds, toy breed purebreds must meet basic standards and criteria for things such as coat, weight, and overall appearance to be properly authenticated by a kennel club. Not every breed has a toy category recognized by respectable kennel clubs. Chihuahuas do not, for example, but poodles do. With careful breeding by ethical breeders who value health over appearance, these small versions can be as healthy as well-bred large versions.

Toy breeds should not be confused with “teacup dogs.” Teacup dogs are tiny dogs who result from the breeding of two very small parent dogs, with the goal of making the offspring as small as possible—sometimes even less than one pound. Their tiny size imposes a wealth of health risks, and no respectable kennel club recognizes them as a subset of a breed because it doesn’t want to encourage their breeding. For toy breeds, size, weight, health considerations, and other affects are standardized by the industry. There are no such standards in the teacup world.

Those of us in the animal welfare world consider a breeder “legitimate,” meaning high-quality and respectable, if he or she adheres to standards, guidelines, and protocols that safeguard the health and well-being of the dogs and promote the likelihood that puppies will be born healthy and their mothers will be kept healthy during childbirth. Many legitimate breeders specialize in one breed of dog and only own and sell this particular breed. Legitimate breeders only use healthy dogs for breeding, do not breed teacup dogs, and ensure gene pool diversity by not overbreeding the same dog or inbreeding by the forced mating of family members.

With the advent of DNA testing, genetic problems can be detected and avoided instead of being passed from parent to puppy. Such genetic tests cost from $75 to $300 and can help breeders determine the likelihood of such things as spinal cord disease, red blood cell defects (causes of anemia and liver failure), and hip problems. The tests provide important information to breeders, so they know which dogs to breed and which not to breed. This gives comfort to the buyers and a better quality of life to the dogs. The cost of the test can be packaged into the price the consumer pays for the dog. The DNA kits, which are regularly used by legitimate breeders, are easy to purchase and the tests are simple to run.

People whom members of the animal welfare community refer to as “illegitimate breeders” are rarely concerned with genetic testing. They also often breed by inbreeding. Because it doesn’t require the acquisition of dogs from other breeders, inbreeding is considered to be a lazy and cheap way to create offspring. It’s particularly popular with illegitimate breeders of purebreds because by only breeding dogs they already own, they can guarantee there’s no “contamination” from another breed. Inbreeding is extremely dangerous because it eliminates or severely shrinks, depending on how closely related the mating animals are, genetic diversity, which is required to avoid passing genetic diseases and disorders to progeny. The demand for dalmatians created by the 101 Dalmatians films led to indiscriminate inbreeding, which resulted in generations of dalmatians being born deaf and/or with a bladder disease.

A human example of the consequences of inbreeding that I learned in school and have never forgotten is the story of hemophilia and the British royal family, often called “Queen Victoria’s curse” or the “royal disease.” In the nineteenth century, Queen Victoria’s family engaged in a practice common among royals from all over the world, only marrying other royals, that is, relatives sleeping with relatives. In Queen Victoria’s family, it led to the spread of a genetic disease, hemophilia, which is a blood clotting disorder carried in a recessive gene that can become dominant when two carriers have children. This led to the untimely deaths of several family members.

Because breeders are deciding which dogs should mate, there has to be diversity and care taken to avoid the likely passing of genetic diseases and disorders. There aren’t enough legitimate breeders to satisfy the demand for name-brand purebreds, and the public responds by buying them, knowingly or unknowingly, from illegitimate breeders. What compounds this problem is that even when people are determined to only buy from legitimate breeders, they are often deceived into buying from illegitimate ones after seeing a falsified paper of authentication from a kennel club.

As poorly bred dogs flood the market, they breed with other poorly bred dogs and their offspring come out even worse off than their parents. Entire breeds could be ruined this way and a point may come when it’s too late to “unbreed” defects and breeds will be permanently damaged.

Custom-designed dogs are the second type of designer dogs. Custom-designed dogs are the result of a breeder mating dogs of different breeds to create puppies who have characteristics of each parent’s breed. In their engineering, the breeder has certain looks and behaviors in mind for the offspring. Custom-designed dogs are bred at a buyer’s request or because a breeder expects that the mixed-breed puppies will be in high-demand—in other words, profitable.

Some proponents of custom-designed dogs argue that these dogs are healthier than other dogs because their gene pools have more diversity. Another argument is that custom-designed dogs can be bred to have qualities favorable to humans, such as being hypoallergenic. There is a misbelief that moral and knowledgeable breeders can guarantee healthy custom-designed dogs with the desired results.

In fact, however, creating a custom-designed dog is an experiment and the results can’t be guaranteed. Legitimate breeders will use two well-bred purebreds, but, even then, the results are unpredictable. If two hybrid dogs are paired, their progeny is even less predictable. If breeders intend to create a “custom-designed breed” and not just make a one-off design, the process is open to a greater number of potential problems because multiple dogs are involved in the process. Creating a new breed requires the ongoing breeding of two parent breeds. This excessive birthing can be dangerous to mother dogs and to all puppies resulting from the breeder’s experiment. There’s a high probability that the puppies will have genetic deformities as a result of the mixing of their parents’ genes.

Incredibly, I’ve heard purchasers of dogs from “custom-designed breeds” brag that they have a purebred, a purebred goldendoodle, for example, which is a cross between a golden retriever and a poodle. There is no such thing as a purebred mixed-breed dog. Whenever I try to set them straight, I’ve been met with fierce resistance. Some people even reference certificates of authenticity they’ve received, as if these are evidence of a purebred. I think the fervent defense of ownership of a “purebred mixed-breed dog” and the claims that custom-made dogs are better than other dogs are the result of a custom-design mania. Once celebrities are photographed with custom-designed dogs, public desire for similar dogs soars.

The demand has been met with a flood of “knockoff” dogs. As with purebreds, legitimate breeders aren’t able to satisfy the demand for custom-made dogs. Ethical and responsible breeding is a slow process, and well-educated, credentialed breeders are careful and loyal to the integrity of the breeds they produce. Illegitimate breeders, such as the operators of puppy mills (a common term for high-volume, low-quality breeding places), use less scrupulous practices. They overbreed and crossbreed to satisfy demand. They’re negligent, and their dogs are given poor-quality shelter, food, and veterinary care, or sometimes no care at all. The puppies they breed are frequently damned to a life of physical and mental illnesses from genetic flaws and poor upbringing.

Most people don’t know they’re buying designer dog knockoffs, and others don’t care. As with anything designer—such as purses, shoes, watches, and luggage—for every person who has an original, there are countless others who have fakes. People buy designer items because they like the look of the item, but they also buy them to look a certain way to others. For many people, it’s important to look the part, whether you are a genuine billionaire or an imposter.

Custom-designed dogs from legitimate breeders and knockoffs are pricey. So pricey, in fact, that their cost often exceeds the combined cost of their parents, even if the parents are purebreds. In 2017, TMZ Sports reported that NBA star Stephen Curry paid $3,800 for a goldendoodle because the puppy had green eyes like Curry’s wife. I wonder if the seller told him that a dog’s eyes change color with age! Curry can afford a pricey dog, but other people determined to own a custom-designed dog may enter into predatory financial arrangements with disastrous consequences, having to pay both the purchase price and care costs for the dog.