Читать книгу Hercules the Bear - A Gentle Giant in the Family - Maggie Robin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

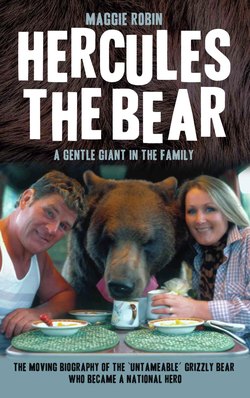

THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM

ОглавлениеLong before we were married, Andy and I agreed that we would do everything we could to share our lives with a wrestling bear. This was to be no ordinary wrestling bear, however, chained and trained only to entertain, degraded into a dangerous clown. That was not the idea. Andy had a vision of an animal that would spar with him on equal terms, a friend and companion whose dignity and independence would be recognised, and who would show the world that trust and companionship were the only ways to achieve results; a wrestling bear who would discredit for ever the tradition of bearbaiting and wrestling with mutilated animals.

We knew that the chances were slender, and the responsibility enormous. A bear can live for up to forty years and cost a fortune to feed. Our whole lives would have to be devoted to him.

Bears were so much a part of Andy that it never occurred to me to question his obsession. I met my first bear in the bear park on Loch Lomondside, where we were enquiring about cubs. An enormous she-bear with two little teddy bear cubs crossed the road in front of our car. She came round and glared menacingly through the car window, which was mercifully closed, and then went on her way. I was very afraid, but nevertheless, from that moment, I was infected by Andy’s enthusiasm.

Finding a bear to own was a different thing altogether. Some zoos adopted an incredulous and snooty attitude towards us: they agreed it was preposterous to suppose that such unpredictable and extremely dangerous animals could be made ‘pets’ of, and they were not prepared to sell a bear into the barbaric slavery of chained performance. We thought at the time, ‘What difference is there between chained performance and close imprisonment?’ and tried elsewhere.

Then, in December 1974, we heard that a she-bear in the Highland Wildlife Park at Kincraig was pregnant. We contacted Eddie Orbell the director, and after meeting us he said he was prepared to sell us a cub for £50, but he insisted that the cub remain with its mother until it was weaned. He didn’t expect that we would keep the cub for more than a week. At this time Mary, the she-bear, had not yet given birth.

There were three cubs in her litter, christened by Andy: Atlas, Hercules and Samson. Atlas was the largest, and Samson the smallest. They seemed more adventurous than Hercules, rolling about and playing with one another, while Hercules stayed close to his mother. We saw them first in February 1975, and were captivated by their antics, especially by little Hercules. He was already standing unsteadily on his hind legs like a little furry man and had a ring of white baby fur round his stumpy neck.

We left him to suckle under the expert and gentle care of Eddie and said that we would be back as often as we could to keep up with his changes. Over the next seven months we travelled to Kincraig many times, watching him grow in leaps and bounds, until the great day came when he would be ours.

We had borrowed a crate from Edinburgh Zoo and travelled up in our Volkswagen caravanette, towing our horse trailer to enable us to spend the night in the park and leave in plenty of time for moving Hercules the next morning. That evening we drank mugs of cocoa and went over our plans with Eddie and his wife, Joanne. Although we couldn’t persuade them that we would achieve our dream, at least Eddie could see that we would take great care of his precious baby. This in some measure allayed his doubts about letting us have Hercules in the first place.

We were up with the birds next morning, impatient to get on with the difficult task of moving Hercules away from his mum and into the horsebox. He was ten months old and weighed 13 stone. Even at this age he was stronger than the average man. It was necessary to tranquillise him before moving him. Eddie gave him the shot while we all kept clear of his sharp teeth.

Even as he went under, his little lip curled in a half-hearted snarl of defiance, but by the time he came round we were ready to go. Farewells were said and everyone agreed that they expected to see Hercules back within the month, but all were very interested to hear what the outcome of our adventure would be. We backed the trailer carefully down the cinder track and were off on the open highway to Sheriffmuir, stopping after an hour or so to make sure our precious cargo was safe, and have a bite of breakfast in a Little Chef restaurant.

Over the blue Formica table we wondered nervously how long Hercules would take to adapt. Would the movement of the horsebox throw him into a rage? Andy had saved a piece of his roll and spread it with tomato ketchup as a treat for our new baby. He took it gently and his little sleepy eyes lit up as he licked off the sweet sauce.

We had built a spacious den for Hercules behind the Inn, very close to the back door. It was made of white-emulsioned stone and connected to an area almost as big as the house itself, which was securely surrounded by a high fence of iron bars. In the den were a couple of rubber tyres, a tree trunk and various other toys for our new baby, and beside it was a hayshed.

Our first task was to move Hercules from his crate into his new home, and this time it would be without any tranquilliser, so you can imagine the tingling nervousness we felt as we realised that anything could happen. Gently, we backed the trailer up to the small door of the den, leaving just enough room to drop the ramp, and slid the heavy crate into the entrance. By this time Hercules was slowly and deliberately weighing the situation up as he stood on all fours, fully awake and ready for action.

As we opened the sliding door of the crate he took off at a rate of knots, panic-stricken, but thinking clearly enough to try to establish the best way out – and hopefully away from these strange new people who now had such a say in his life. Within seconds, he disappeared into his sleeping quarters, noticed immediately a gap between the top of the wall and the hayshed and frantically tried to climb up to it. He seemed to spot every potential escape route within seconds, his eyes darting this way and that and missing nothing. His instinct for survival had put him on the defence right away.

After about fifteen minutes he began to settle down and wandered from one part of his den to the other, sniffing at corners and handles. We watched him silently, and then, out of the blue, Andy announced that, if they were to begin getting to know each other, there was no time like the present to start. We were still the enemy, but what would young Hercules’s reaction be if the hand of friendship were offered?

It didn’t take long to find out. Armed with a large carton of strawberry ice cream Andy entered the outside run. The cuddly little bear wore an expression of deep suspicion as he stood his ground, eyes wide with fear. Both parties then remained perfectly still, each leaving it to the other to make the first move. After some time the little black button of a snout sniffed the air in the direction of the offered goodies and slowly took the first step towards the source of the smell. I was rooted to the spot as I watched Hercules draw closer towards Andy’s outstretched hand. Then he was there. Out popped his little pink tongue and he hungrily got stuck into the proffered peace offering.

It all seemed too easy, and, sure enough, once the titbit was finished, the sharp white teeth – now bigger than the last time – were again sunk into Andy’s hand of friendship.

Andy’s free hand delivered a sharp smack on Hercules’s snout and he quickly dropped his second ‘snack’, now very bloody, with a look of amazement. It was to be the first of many battles with the wild young creature.

As autumn turned to winter we came to understand the tenacious instinct for survival in our growing friend. Each day was spent planning and working around Hercules, trying to overcome every setback as we came upon it. After the bout with Terrible Ted in Canada, Andy had sought out the bear’s trainer, Gene DuBois and had learned a lot about the likes and dislikes of bears. Also he had been continually told of their innate treachery as a species.

Andy’s physical strength and agility, and his wrestling background, made him better able to dodge the swift snaps and buffets aimed at him by the young bear and very gradually his courage and kindness seemed to get through to the suspicious young creature and win a glimmer of respect.

It was two months before I could even dare to touch him, and even then I had to withdraw from him very quickly before I had my hand mauled. It was a time of slow progress and many disappointments.

One of the earliest problems was to persuade Hercules to wear a collar and lead. It was like breaking in a stallion with very sharp teeth. Andy would move in as close as he could and catch him with a lasso. Hercules would tense his neck and dash about the den knocking Andy from wall to wall and diving in as often as possible to bite any part that he could reach. It was only superhuman determination that prevented Andy from giving up at this stage, but he knew that the moment Hercules felt he had the upper hand all that he had achieved so far would be lost.

No sooner was this hurdle cleared than we had to embark on the even more difficult task of persuading Hercules to wear a muzzle. He wouldn’t have to wear it all the time – only when he was wrestling – but it was important to get him used to it as early as possible, and he was now nine months old. All those who had trained bears said that this had been too late to start but we had no alternative and ploughed on hopefully.

The first thing was, to have a muzzle made that fitted him properly. There were no handy manuals or textbooks to offer us guidance in this. It was a case of trial and error. The first muzzle was made of leather and consisted of a strap round Hercules’s neck joined to two other straps around his nose that hung fairly loose. This was to get him used to the idea of having a ‘bridle’ on. To put it on him was a matter of bribery in the form of ice cream, grapes and yogurt, and very quick reflexes when he decided he’d rather have a bite at our arms instead.

We continued this for about a month, and only after this time would he allow us to work about his head, slipping the muzzle on and off without fuss.

In December it began to snow. Hercules had been with us now for four months, and, when we looked out of the window that morning after the first snowfall, we saw him happily burrowing his way under the deep snowdrifts in his den. I made breakfast of porridge and cream for Andy and me, and a great pot of beans, eggs, cod-liver oil and bread for Hercules. We topped this off with a large pot of tea with milk and sugar for all of us, and we were all ready to start the day. Hercules rushed out of his den and followed us into the paddock on his long lead, rushing about, madly diving into snow drifts until all you could see was his little furry bottom sticking up in the air against the brilliant white of the snow.

One of his favourite pastimes in the snow was sledging. He learned the skill accidentally on a large plastic container that he found in the paddock, discovering that if he placed his big front paws on it he could then push at the ground with his back paws and slide easily down the hill.

By the early spring we really thought we had a chance of proving the experts wrong. Not only was Hercules still with us, but we seemed to be making daily progress in our relationship with him. It’s true that he was by no means a household pet – it was not our intention to turn him into one – but neither was he the fierce creature that he had been when he arrived, as most bears in captivity remained.

From the beginning of the ‘experiment’ the press had taken an interest, and they kept an eye open for developments as the months went by, tending to dwell on setbacks rather than achievements. There was, sadly, never any shortage of people to criticise and complain of danger. They usually took the line that it was for our own benefit, that we didn’t know what we were doing, that we had no training in the handling of dangerous animals, that sooner or later there would be a fatal accident. In spite of it all we persevered; they could do little to harm us – or so we thought.

It was necessary for us to obtain two licences to keep Hercules: a Performing Animals Licence, which would enable us to train him and to entertain others with him; and the Dangerous Wild Animals Licence, a new licence introduced in April 1977, which would enable us to keep an animal specified under the Act that introduced it.

The first licence could be obtained only if the keeper had some experience of working with the animal in question and could show that his treatment of the animal and the conditions under which the beast was kept fulfilled the legal requirements. Local police and vets who had carefully monitored us since before Hercules’s arrival lent their support to the application and the licence was obtained without any difficulty.

The second was a different matter. Because it was a new piece of legislation, the local council was unsure of how stringent it should be, and, since we were the guinea pigs, it wanted to make absolutely sure.

Although we had not seen a copy of the Act, we were told that it applied to us and were asked to send off details of the size of Hercules’s den, the strength of the material it was built from, the number of warning notices about the place and so on. We were well above the required standards and supposed that it would simply be a matter of time before the necessary piece of paper arrived.

We were wrong. Stirling Council met once every fortnight and at meeting after meeting the application came up and was referred for further information. We couldn’t believe it. Andy wrote to the authority suggesting that the surest way of judging was for members to visit the Sheriffmuir Inn and see for themselves, but they declined, preferring to continue ‘considering’ and ‘referring’ from the council chamber.

By this time it was becoming ridiculous and beginning to attract the attention of the local papers. It seemed that, although the council could not find any legal grounds for refusing the licence, there were several councillors who did not like the idea of a grizzly bear roaming about the hills of Sheriffmuir and were determined not to be rushed into any decision. After several months even the councillors were looking for a way out and decided to visit the Inn.

We were given pre-emptory notice of this and then were plagued at all hours of the day by the comings and goings of councillors, arriving without appointment and expecting to be shown round and given the full treatment.

We both felt irritated that these bureaucrats could arrive and roam about our home pulling at bars, opening doors and measuring things that had all been tested and measured before. Matters came to a head one Sunday with the arrival of a woman councillor.

I had been working hard in the bar all week and was enjoying a peaceful afternoon mucking out the horses. I was about to go for a ride across the moors when I noticed a heavily made-up elderly woman in an imitation fur coat making across the yard and boldly opening the gate.

‘Can I help you?’ I asked.

‘I’m from the council,’ she said. ‘I’ve come to see your bear.’

I closed the gate and followed her to Hercules’s den.

‘There he is,’ I said, ‘that’s my baby.’

She looked at me as if I was mad and, hauling the plan of the enclosure from her bag, proceeded to walk round the den checking and testing things. As I watched her I could not fail to be struck by the contrast between the natural grace of the wild creature behind the bars and the phoney elegance of the human outside. A comparison between their coats made me smile involuntarily – the one so rich and glossy, the other so dull and tawdry. At that moment Andy arrived on the scene. I grimaced at him to let him know that something was up.

‘Can I help you?’ he asked.

‘I’m from the council. I’m here to see your bear,’ she said again.

‘What do you think of him? He’s a beautiful boy, isn’t he?’ asked Andy.

‘No comment,’ was all she said.

‘I beg your pardon …’ began Andy. I slid away to avoid the explosion. Where Hercules was concerned he reacted as most fathers would.

From the kitchen I saw the councillor wither under Andy’s broadside and the next minute she was in the bar, dragging away an astonished man from his half-pint.

‘I’ll not have you drinking in this place,’ she said as she hurried him into her car and drove off, scattering stones.