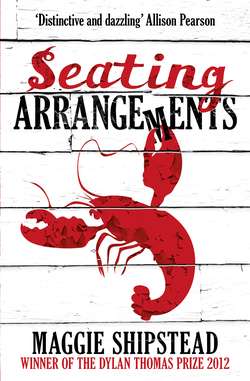

Читать книгу Seating Arrangements - Maggie Shipstead - Страница 13

Three · Seating Arrangements

ОглавлениеBiddy stood with her hands on the edge of the kitchen table, leaning over a slew of guest lists, place cards, and seating charts. She felt like a general planning an offensive. Beside her, Dominique, faithful aide-de-camp, mirrored her posture.

“What if,” Dominique said, switching two cards, “we move these like this. Situation neutralized.”

“No,” said Biddy, “because then I’ve got exes sitting at the same table. Here.” She touched the paper.

“They wouldn’t be okay?”

“It’s not ideal.”

Dominique tapped her lips with one long finger and considered. Biddy, seized by affection, patted her on the back. She missed Dominique, especially during the holidays, when she had been a household fixture all through high school and college, Cairo being so far away. Dominique had been the sort of worldly kid who sought out the company of adults and who, at fourteen, had considered herself all grown up. When she stayed with the Van Meters, she behaved more like Daphne’s indulgent aunt than her friend and spent most of her time helping Winn in the kitchen and running errands with Biddy while Livia, little duckling, followed wherever she went and Daphne lay indolently in front of the television. Agatha had spent a few holidays with them, too, but her presence was less comfortable. Biddy was always finding cigarette butts in the flower beds and catching Winn staring and waking up to the sound of Agatha laughing and drunkenly thumping the walls while the others shushed her and tried to convey her to bed. Once Biddy had gotten up and flipped on the light at the top of the stairs, surprising them—Daphne, Dominique, Livia, and Agatha—like a family of possums in the sudden brightness. Agatha was lying on her side and inexplicably clinging to the balusters while Dominique worked to pry her fingers loose and Livia and Daphne grasped her ankles to keep her from kicking.

“What if,” Dominique said, pointing at the seating chart, “we move him to the leftovers table?”

“Yes,” said Biddy. “Perfect. But I feel bad calling them leftovers.”

Dominique pushed the place card across the table with the authority of a croupier. “Le mélange, then.” She stood back and looked at Biddy, her long eyebrows kinked and her long, sad mouth pulled quizzically to one side. “How are you? I mean—really.”

Biddy was so surprised by the question that her eyes began to water. “I’m fine,” she said, fussing with the cards to indicate the unimportance of her tears. “I’m great. I’m so happy for Daphne—I want everything to go well.”

“Of course you do,” said Dominique. “This is an insane amount of work. You’re handling it like a champ.”

Biddy was forced to take a tissue from the box on the counter. She never wore mascara, but she dabbed carefully nonetheless, coming up under her lashes the way she remembered her mother doing. To be seen, really looked at, the way Dominique had fixed on her, was unsettling. Her family barely noticed her, but she couldn’t blame them: she had changed so little over the years that people were never reminded to reconsider her. “It is a lot of work,” she said. “It really is.” Making the confession gave her a small thrill, and she went on, feeling her way. “And sometimes it feels like a natural conclusion to raising a daughter, that you run yourself ragged to make this one day as perfect as possible, even though, for you, the day is bittersweet because she’s leaving—I mean, she’s been living with Greyson, but somehow this is different, more official. I don’t know how those over-bearing beauty pageant mothers do it, you know, keeping track of someone else’s whole physical being: hair, clothes, makeup, all that.”

“Yeah, right?” Dominique concurred. “I think—well, I don’t know, but it seems to me the real backbreaker is being in charge of manifesting someone else’s idea of perfection. Not necessarily Daphne’s, just this idea floating around out there about what a wedding should be.”

Biddy squared a place card with the edge of the table. “Manifesting someone else’s idea of perfection. Hmm. That’s well put.” She wondered if the younger woman was talking about more than just the wedding. Certainly Biddy was no stranger to laboring under another person’s vision for life. Abruptly, her enjoyment of her own honesty peaked and fell away. She had wilted quickly under the spotlight. “I don’t know,” she said. “All I mean is that I don’t want anyone to be disappointed.”

“Well, sure,” Dominique said, switching to an offhand tone, “but there’s only so much you can control. Perfection is overrated, anyway. I’m all about meeting basic needs and seeing what’s left over from there.”

Laughing in embarrassment, Biddy balled up the tissue and hurried to throw it away under the sink. “But you! I want to hear about you,” she said. “You have the most interesting life. Tell me everything about Belgium.”

“Oh, it’s all right. I don’t think it’s my forever home. I just kind of live there. In a way, it could be anywhere. You should see my apartment—it’s completely barren. Every time I think about buying something, like nice sheets or something to hang on the wall or even fancy hand soap, I think, well, no, because I won’t be here for long, and it’ll be one more thing to get rid of.” She gave Biddy another searching look. “Are you sure you don’t want to take a break? You could run away for an hour somewhere. Have some time to yourself. I’d cover for you.”

“No, no,” Biddy said, shaking off the last of her tears. “I’m really fine. It’s not the amount of stuff I have to do, really, it’s—you’re so sweet to ask. I just—where is your forever home, do you think?”

Dominique’s eyebrows climbed a notch higher, but she said, “I’m not sure it exists. Not Egypt, not Belgium. Not France—that’s where my parents live now. They moved a couple of years ago. I don’t know if Daphne told you. I like New York but it exhausts me. Not Deerfield. Not Michigan.”

“That still leaves a lot of places,” Biddy said. “Maybe you’re supposed to live in the Bahamas.”

“I hope so. In a hammock.” They giggled.

“How will you find it?” Biddy asked. “Your home?” She was curious; she had never chosen where to live.

“I think probably I’ll look for a job first. But—I don’t know. In theory I could work most places. You’d think it would be fun, being able to pick more or less anywhere in the world, but when I think about the freedom I usually just end up feeling lonely. There’s nothing pulling me to any particular spot except vague preferences. And sometimes I wonder what it says about me that I can drift like this.” She gave a quick, wry roll of her eyes. “Total first-world problem.”

“What do you mean?”

“You know, like, oh, woe is me, I’m so exhausted and alienated by my globe-trotting life of preparing expensive food.”

“Don’t you have a boyfriend in Belgium? What about him?”

“I don’t think he’s permanent.” Dominique made a slow, sheepish shrug, her shoulders lingering around her ears for several seconds until she abruptly let them fall. “It’ll all sort itself out. Where do you think I should live? Where would you go?”

Biddy was caught off guard not so much by the question as by her inability to process it. She couldn’t think of a single place she might live where she had not already lived. She thought: Connecticut. Waskeke. Maine. Connecticut. Those weren’t answers for Dominique. They were shameful in their timidity, their lack of adventure. But she could not imagine living on a tropical island or in the Alps or in Rome or Sydney or Rio. She could not imagine living in Delaware. “I think you’ll know it when you find it,” she said. “I think you’ll find the perfect place. Or at least one that meets your basic needs.”

The side door slammed, and Livia appeared in the hallway, balancing a paper grocery bag brimming with corn on each of her hips. “Teddy joined the army,” she announced.

“Teddy Fenn?” Biddy asked.

Livia set the bags on the counter. “Teddy Fenn.”

The boy’s name, so familiar, sounded foreign to Biddy when Livia pronounced it all by itself, like the Latin name for a rare species, some kind of wetlands bear. “How do you know?”

“We ran into Jack at the market. He said Teddy just went down to some recruitment center or wherever and signed up. He’s not coming back to school. He’s not graduating. I don’t know why Jack couldn’t stop him. What kind of father would let this happen?” Biddy thought Livia sounded like her own father, though Livia would be offended to be told so. The two of them had the same wrongheaded belief in the power of parents over children. A bag of corn tipped over, and the heavy ears thumped onto the floor. Livia gazed heavenward and flapped her arms in defeat.

Biddy was relieved not to be the object of any more scrutiny. “Easy does it,” she said, approaching her daughter even though she knew her consolation would not be welcome. Since Livia could not admit defeat and accept that Teddy really was lost, she would tolerate no pity. Biddy kept waiting for her to simply get over the boy. As a toddler Livia had been inseparable from her pacifier until the day she was put down for an unwelcome nap and ripped the rubber nipple from her mouth and hurled it to the floor, never to suck on it again.

“Dad was in rare form,” Livia said after allowing Biddy a brief hug and then stepping away. “He got all, you know, forceful and cheerful, and tried to bring up the Pequod and was weird with Meg, and then, then, he goes, ‘How is Teddy?’ Like he was talking about some random acquaintance. And Jack says, ‘Oh, funny you should ask. He’s made a big decision. He’s joined the army.’ And Daddy says, ‘Well. Well, well, well, well, well.’ Like that. ‘Well, well, well, well, well.’”

“Did Jack say why?”

Livia bent to gather up the corn. “No. I’m not sure he knows.”

“Where does he go? Does he go to … boot camp?” Biddy spoke tentatively, uncertain of the expression.

“I don’t know. I have no idea where or when or how. I don’t know. Why would I know? Did he just wake up one morning and decide, Oh, none of this is really working for me? I’d like a one-way ticket to Iraq, please.”

“They’ll give him a round-trip ticket,” Dominique said. She, too, came to hug Livia, and this time Livia seemed grateful, wrapping her arms around Dominique’s strong back and hiding her face in the young woman’s shoulder. Biddy noticed a strand of corn silk on the tiles and bent to pick it up.

“He might have to come back as cargo,” Livia said, muffled. “Why can’t he just finish college?”

“Livia,” said Biddy, “I don’t want you to think this has anything to do with you.” She reached in from the outskirts of the embrace to squeeze her daughter’s shoulder.

“That’s what Daddy said.” Livia released Dominique. “But how could it not have anything to do with me?”

Because, Biddy wanted to say, Teddy didn’t fall apart after this breakup the way you did. Because Teddy’s life no longer includes you. But she could see that Livia was taking Teddy’s decision as some kind of sign, an indication that he was becoming unpredictable and erratic, possibly on the brink of a collapse that could only drive him back to her, regretful and awakened. His flight to the army was the last dying flutter of independence, his last binge of freedom before he saw the light. The army would never love him the way Livia did. “I don’t want you to hope it has something to do with you,” Biddy said.

Livia began breathing in through her nose and out through her mouth and staring off into space. The therapist she saw at school, Dr. Z, had taught her that trick: if you feel like you’re about to lose your temper, breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth and count to five or ten, depending on the direness of the situation. Winn hated that Livia saw a shrink. He said she should learn to grin and bear it.

“Anyway,” Livia said after five seconds, “after we saw Jack, Daddy decided we should go check on their new house.”

“The Fenns’ house?” said Biddy. “Why?”

“I think he wanted to sit there and glower at it and think about the Pequod. Not about how Teddy knocked me up and dumped me, no, no. About how unfair it is—what a great injustice it is—that there’s a club out there he can’t join.”

“Maybe it’s easier for him to think about the Pequod,” Dominique said.

Biddy looked at her, annoyed. The casual analysis seemed to violate Winn’s privacy. And Dominique couldn’t possibly understand what his clubs meant to him, what it was like to live inside their particular social world. Hadn’t she just been saying she didn’t belong anywhere?

Dominique was standing at the counter with a bottle of white wine she had helped herself to from the fridge, presumably to pour a nerve-settling glass for Livia. The natural melancholy of her face lent an air of pensive deliberation to even her simplest actions, and she contemplated the bottle as though it were a bouquet of condolence flowers in need of arranging. Thoughtfully, slowly, frowning, she twisted in a corkscrew and then glanced up, catching Biddy’s eye and, surely, some trace of her enmity.

“You know what I mean,” Dominique said levelly. “We all have our safe thing to run back to when we get overwhelmed.”

Biddy remembered that only minutes before she had been grateful enough for Dominique’s presence to have cried. Apologetically, she said, “He likes to keep track of new houses on the island.”

“Honestly, I think the house is great,” said Livia. “They have an amazing location. The house is big, but so what? It’s Fenn Castle.”

“The Fennitentiary,” Dominique said, handing a glass of wine to Livia. “Biddy, may I pour you a glass?”

“No, thanks.”

“Fennsylvania,” said Livia.

Biddy tried to think of a pun but couldn’t come up with anything. Had Dominique ever even met any of the Fenns? Most likely not, though certainly she had heard plenty about them—both Daphne and Livia kept up e-mail correspondences with her, and over the past few days the house had effloresced with girl talk. “Is Teddy on-island?” she asked Livia.

“I don’t know. I didn’t ask. Probably.”

“Well, you won’t run into him.”

“What if he calls me?”

“Do you think he will?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. You’d think he’d want to tell me about the whole army thing.”

Biddy sat back down at the table.

Livia stepped closer and studied the mess of cards and charts. “Shouldn’t Daphne be doing this?”

“Seating isn’t really Daphne’s strong suit,” Biddy said. “She gives everyone the benefit of the doubt. She doesn’t see where conflict might arise.”

“On the other hand,” Dominique said, “I assume the worst.”

“You’re very good,” Biddy said. She reached across Livia to pat Dominique’s hand.

“Do you know all these people?” Livia asked Dominique.

“Not all of them,” Dominique said. “Biddy’s been explaining the web.”

“The web?”

“All the connections between everyone. It is impressively tangled, I will say.”

“Do you think Daphne’s strong suit might be shucking corn?” Livia asked.

“I’ll help you,” Dominique said. “Wine and corn shucking is an underrated combination.” She turned to Biddy. “We’ve pretty much got the seating stuff figured out, right?”

“Sure,” Biddy said, so practiced at concealing her disappointments that she had no doubt she sounded serene, even cheerful, as they abandoned her. “I’m fine here. You girls go on. Have fun.”

Through the French doors, she watched them settle into Adirondack chairs, glasses of wine on a table between them, and take up ears of corn. They ripped the green husks and pale clumps of silk free of the cobs, and dropped the naked yellow ears in one paper bag and the husks in another. Livia was talking, talking, talking, and Dominique was listening as she expertly shucked the corn, her eyebrows curved in tildes of concentration.

Biddy could no longer bear to watch Livia talk about Teddy, her eyes shining with wounded zealotry. Looking away from the girls, she made a few final desultory attempts at seating gambits that would ensure everyone’s happiness at the reception, and then she sat staring into the kitchen, wondering what to do. She could think of no more confirmation calls to make, no more gift bags to fill, no flowers to wrangle, no people to greet until the Duffs showed up for dinner. Usually e-mail was banned from the Waskeke house, necessitating a family trip to the library in town every couple of days, but this time Livia had insisted on having a cable hookup put into Winn’s office. Biddy wandered in that direction although she didn’t really want to know what new obligations were waiting in her in-box, and she only had to open Livia’s laptop and see the photo on the desktop—Teddy was not in the picture, but it was one Livia had taken on a trip with him to Scotland—to decide that, no, she would not check her mail after all. Perhaps she would follow Dominique’s advice and take a quiet moment for herself.

She sat in Winn’s chair, a winged, brooding, swiveling leather thing, and pivoted slowly around. Out the window she saw Daphne, Piper, and Agatha lounging on the lawn, but she had no desire to watch them and continued turning until she was again facing the green expanse of Winn’s blotter, bound at the sides with gold-embossed leather and clean except for a small stack of unopened mail and, all alone out in the middle, a single bobby pin. Biddy picked up the pin and held it in the light, looking for any telltale hairs, but it was clean. She supposed Livia must have left it there, though why she would be fixing her hair at Winn’s desk was a mystery.

She swiveled again to look out the window. At the rate Livia was going, she would end up being as scrawny as Piper, whose shoulder blades cast angular, inhuman shadows as she stretched her knobby arms up and out to the side. Of course she might have been as big as Daphne by now, or bigger, or already a mother. Biddy was afraid Livia was the doomed, clever moth who does not just bump against the outside of the lantern but manages to find a way inside and breaks itself against the glass—maybe trying to escape, maybe trying to merge with the flame. Biddy fiddled with the bobby pin, turning it over and over, pinching her fingertip in its tines. Teddy was a handsome kid, comfortable being noticed, impish and urbane under his red hair, not too pale but freckled, almost golden. He was friendly and charming, too, but Livia seemed unaware of how far she outstripped him in curiosity and sharpness and passion. Yes, Teddy had told Livia he loved her, but Biddy, for all her sorrow at her daughter’s pain, was disappointed and troubled that Livia had allowed herself to become so vulnerable, mulishly ignoring all the warning signs. How had she, Biddy, managed to raise someone so exposed and defenseless, a charred moth, a turtle without a shell, exactly the kind of woman she most feared to be?

CELESTE LAUGHED a hooting, triumphant laugh, pleased to have startled him so completely. Winn, turned pure animal, had bolted off to one side, his body twisting in its unimaginative sheath of polo shirt and salmon-colored pants. His feet, trying to flee, had run afoul of the tree roots, and he had stumbled badly, catching a trunk with both hands. She knew from long experience that taking jokes was not Winn’s strong suit, but still she was unprepared for the intensity of the response that crossed his face: first a very brief flash of something odd, like fear but also like despair, and then, once he had steadied himself, pure rage.

“What the hell are you doing?” he demanded.

“Come on, Winnifred, just a little prank. You didn’t die.”

He examined the palm of his left hand and held it out for her to see. It was pink and scratched. Tiny white curls of skin stood up like grated cheese. “This is the last thing I need.”

“Good thing you’re not a lefty.” Earlier, Celeste had sensed she was getting too far ahead of the game and had come out for a walk to sober up. She was glad, too, because now she could be confident she wasn’t slurring her words.

His face resolved into a grim smile. “How much have you had to drink?”

“Just the right amount,” she said. She hoped the medically smoothed forehead she wore like a helmet would keep her from betraying the sting of his question. “What are you doing out here, skulking around?”

“I wasn’t skulking. You’re not the only one who can take a walk. It is my property, after all.”

His discomfort intrigued her. Instinct, honed by years of field experience, had rendered her unable to resist sniffing along a trail of male bad behavior once she caught the scent, and she studied him, increasingly certain that, underneath his bluster, something was off. Winn scowled, backed up against his tree. What had he been looking at in the first place? He moved to block her view, but she leaned around him and caught sight of the girls out in their bathing suits, soaking up the last of the sun like three mismatched lizards. “Enjoying the view, Winnifred?” she said lightly. There were worse things than being a Peeping Tom.

He gritted his teeth. “I was taking a walk. I heard a noise, and I went to see what it was. I was about to go up and say hello to the girls when you decided to give me a heart attack. I didn’t realize you were taking a break between cocktail hours to sneak around.”

“No need to get huffy with me, 007,” she said. He would never dare pick on her drinking with Biddy around, but as they faced each other out in the trees, his dignity ruptured and his adrenaline still running high, they were caught up in a primal energy. She thought he was equally likely to strike her or kiss her. He had kissed her once before, supposedly by accident, and he was attractive in his way, in good shape for his age and with a symmetrical, serious, news anchor sort of face and nice gray temples. But then again she had a thing for repressed men (hello, husbands one, two, and four), and she had a thing for men just starting to go gray (three and four), and she had a thing for forbidden men (three, oh lord, three), and, truth be told, she flirted with Winn sometimes for no more substantial reason than that she liked to keep things lively. She had stolen husband number three in the first place—he had been a charismatic trial lawyer, married, and the authoritarian, despised, partnership-withholding boss of husband number two—and then that little tramp, that child with the long, long legs and the horse face, her best friend’s daughter, had gone and stolen him, and off they’d flown to Bolivia.

But Winn was such a square. That was why he and Biddy worked. Ogling through the pine trees was probably the great sin of his life. “I wasn’t sneaking,” she said. “I was walking, just like you.” She attempted a saucy smirk, feeling a curious deadness in the parts of her face that had been injected into submission. “So, which is it?” she asked.

“What are you talking about?”

“Is it Agatha or Piper? Oh, don’t tell me. I’ve already guessed.” As she spoke, she realized that she had, in fact, guessed, and scorn rose up in her.

“You are being disgusting,” Winn said with exaggerated deliberateness. “I hope you get all this out of your system before our guests arrive.”

She poked him in the belly, just above the brass buckle of his needlepoint belt, finding more softness there than she expected. “Dirty old man.”

“Screw off,” he growled and stomped away into the trees.

Celeste watched him go and then pushed through the branches and sauntered out onto the lawn. “Hello, ladies!” she called. Piper waved; Agatha propped herself up on her elbows; Daphne lolled on her side like a walrus, her chin lost in the soft folds of her neck. Poor dear. Fortunately, she would be the type to shed the baby weight right away.

“What’s up, Celeste?” Agatha said.

Piper sat up straight as a yogi and lifted her arms over her head. Her swimsuit stretched over the hollow between her ribs and hips. “Isn’t it so beautiful out?” she chirped.

Celeste flopped onto the grass. “Absolutely gorgeous.”

“Make sure you check yourself for ticks later, Celeste,” Daphne said. “Lyme is a problem here.”

“Why would limes be a problem?” Piper asked.

“Not limes,” Agatha said. “Lyme disease. With a y.”

Celeste crossed her arms over her face and wished that a hand would descend from heaven and offer her a cocktail. She was wearing shorts and a striped sailor’s shirt, and the grass pricked her calves. She kicked off her sandals and rolled onto her belly, looking uphill at the girls. “So who’s next, ladies? Who’s after Daphne?”

“Don’t look at me,” said Agatha. “Piper’s the one with a boyfriend.”

“Oh my God,” Piper said. “Don’t jinx it.” She ran a hand through the huge mane of hair that, in Celeste’s opinion, made her look like a member of Whitesnake.

“So marriage is still cool?” Celeste asked. “It’s still something girls your age want? I would have thought you all would be going over to some groovy, Swedish hipster model of commitment.”

“Obviously, marriage is cool,” Agatha drawled. “Otherwise Daphne wouldn’t be doing it.”

Daphne snorted. “If I had a baby out of wedlock, Daddy would die. Literally die.”

“You mean,” Celeste said, “you wouldn’t be getting married if it weren’t for your father?”

“Well, Mom, too. And the Duffs. But, no, if I really had my way, we’d wait a while so I wouldn’t have to be pregnant in the pictures.”

“I really want to get married,” Piper volunteered. “It’s so romantic.”

“Yes, it is,” Celeste agreed. She plucked a blade of grass from the soil and tickled her lips with its waxy edge. “But romantic and prudent are not the same thing.”

“That’s good, though,” Agatha said. “Imagine if there was only prudence.”

“Hmm,” said Celeste. “Then I never would have married, and the world would be a very different place.”

“My parents would have, though,” Daphne said. She had settled on her back again, and her voice drifted over her belly.

“That’s true,” Celeste said.

Agatha crossed one golden leg over the other and bounced her slender, dirty foot. “What was Winn like when he was young?” she asked. “It’s just that I can’t imagine it. Biddy I can picture, but not Winn.”

Celeste felt a prickle. The nymphet was interested. Never one to torture herself, she preferred not to dwell on the charms of young women and had only allowed her eyes to skim the girl before, assessing her as pretty (really, more than pretty but with the kind of looks that would turn vulgar before too long). But now she gave her full attention to the remarkable body on display in that ratty old bikini, worn to near transparency. Agatha was thin but not hard. Long limbed but still small. Totally devoid of pores or cellulite or stretch marks or stray hairs. Even something as mundane as her kneecap was finely wrought, worthy of study, top of the line.

But this girl must have her choice of men. Why would she want old Winnifred? What about him could possibly light her fire except his forbiddenness, his unlikeliness, the very triteness of his middle-aged crush? Not that any of those should be underestimated. Husband number three, Wyeth, had been the least handsome but most loved of her husbands, and now he lived off his fortune in St. Barts, the novelty of Bolivia having long ago worn off, though not, apparently, the allure of long-legged, horse-faced youth. But Wyeth had been stolen property to begin with, an unlucky penny, and Celeste, in the end, had come to accept the bulk of the blame for the sorrows caused by their marriage. Nothing like that should happen to Biddy. Biddy had always been such a docile creature, highly competent but docile, happy to be a kind of ladies’ maid to her sisters through her childhood and then an earnest bluestocking and then a selfless wife. To betray her would be the height of cruelty. But this was crazy. Agatha couldn’t possibly want Winn.

“Oh,” Celeste said, drawing an expansive sigh of phony reminiscence, “let me cast my mind back. I think—I think—yes. I remember now. Winn was exactly the same.”

Piper made a high squawk that Celeste supposed was laughter. “There has to be more. Tell! What was he like?”

“Really. I couldn’t possibly come up with one thing that’s changed.”

Daphne stirred. “Mom once said he had a bad reputation before they met. Apparently he liked the ladies.”

Agatha’s bouncing foot stilled.

“I think he started those rumors himself,” Celeste said. “Your father is a born monogamist. Boring as hell.”

“Mom seemed kind of proud of it,” Daphne said. “She’s funny.”

Agatha uncrossed her legs and sat up. The shade had fully caught her, and she rubbed her arms as though to brush it off. She said, “Some people like a little competition. You want to feel like you have someone desirable.”

“You would say that,” Daphne said. “Whatever helps you sleep at night.”

But Piper was nodding. “No,” she said, “I think that’s true sometimes. You want to feel like the guy had lots of options but chose you. Like you tamed him a little bit.”

“That is so retro,” said Daphne.

“Don’t you feel that way?” Agatha asked. “It’s not like Greyson was a virgin when you met. It’s not like Greyson was ever a virgin.”

“Well,” Daphne said. “I don’t know. Maybe a little.”

Sadly, but with a certain pleasure of anticipation, Celeste accepted that she needed a drink. “All right,” she said, hoisting herself to her feet and sliding back into her sandals. “I’ll leave you girls to it. Someone has to tell Daphne what’s going to happen on her wedding night, and I don’t have the stomach for it.”

“We’ll be in soon,” Daphne said. “We’ve lost our sun. Check for ticks.”

Celeste walked around the house and greeted Livia and Dominique, who were deep in conversation on the deck beside two bags of shucked corn. Inside, place cards and seating charts were spread over the table, but Biddy was nowhere to be seen. The bottle of gin was out on the counter, and after she poured a little into a tumbler and added ice and a dollop of tonic, she put it away in a cupboard, where people were less likely to monitor its level. The first sip, bitter and fizzy, was unspeakably delicious, and she felt her nerves begin to settle at once. The bottom line was that she was being paranoid about Winn. And even if she wasn’t, what could she do?

After retrieving the bottle and splashing out a tiny bit more gin, she climbed up through the house to the widow’s walk, where she could have some privacy and fresh air and take in the view. Reclining in a chair, she closed her eyes and pressed the sweating glass against her forehead. She wanted to tell herself she had once been as sexy as Agatha, but her delusions were not so strong as that. Still, she had been seductive. Otherwise she wouldn’t have been able to poach Wyeth from his mousy wife and three children. The best she could say for herself now was that she was the kind of woman people called well preserved. But despite all her restorative efforts, she looked tired. Which she was, in the existential sense. There would be no more seductions for her, no more ecstasy, no more destruction. She and Cooper had a pleasant life together, a sanctuary built by two reformed sinners around a policy of maximal calm and minimal communication. Quiet dinners out, long weeks apart when he was off sailing, compatible taste in TV and movies, mutual tolerance of each other’s friends, agreement that they would never marry. Maybe she had stumbled on the ideal relationship for a woman her age. Maybe, after all these years, she had solved the riddle. Even if things fell apart, she would draft another companion from the bush leagues of washed-up lovers, and they would wait out the violet hour together.