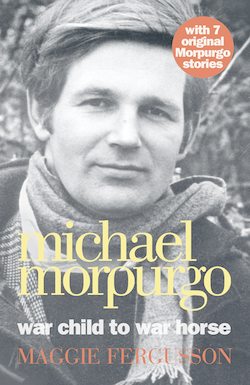

Читать книгу Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse - Maggie Fergusson, Maggie Fergusson - Страница 6

Оглавление1 Beneath the Hornbeam

In a corner of Michael Morpurgo’s Devon garden, the ashes of three people share a final resting-place. The sitting room of his low, thatched cottage looks out on the spot where they lie. He passes it every morning on the way to the summer house where he writes. Above it, a hornbeam tree flourishes with such elegance and grace that you might imagine the ashes beneath must be mingled in invigorating harmony. But you’d be wrong. In life, these three people – Michael’s mother, father and stepfather – caused one another untold pain, giving Michael an early education in what he describes as ‘the frailty of happiness’. If you want to understand the thread of grief that runs through almost all his work, you should start here, beneath the hornbeam.

The first ashes to be scattered, on a cold, bright, blossomy day in the spring of 1993, were those of Michael’s mother, Catherine, known from birth by her third name, Kippe (pronounced ‘Kipper’). At her memorial service the congregation had sung the Nunc Dimittis,

Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace …

and they had sung it with full hearts, because for most of Kippe’s life peace had been a stranger to her. She died an alcoholic, pitifully thin, stalked by depression, and convinced, Michael says, ‘that she had failed in the eyes of God’.

How could her life have become so bitter? If Kippe had been a child in a story one might have said that, on her birth in the spring of 1918, the fairies had been generous at her cradle. The fourth of six children, she was beautiful – fair, with a tip-tilted nose and blue-green eyes – and her looks were coveted by her three sisters, who were plainer and more sturdily built. Her father called her his ‘Little White Bird’, echoing J. M. Barrie’s fantasy of infant loveliness and innocence; and, complementing her face, she had a voice that would draw people to her for the rest of her life. Her younger and only surviving sibling, Jeanne, describes it as a ‘brown velvet’ voice, and in a recording made when Kippe was nearing old age it remains melodious, languid and gently seductive – the voice that lured Michael, unbookish boy though he was, into the wonders of words and stories.

Children outside the family were mesmerised by Kippe. Jeanne remembers, more than once, inviting friends home for tea, only to have them admit that what they really desired was to spend time near Kippe. They were fascinated not simply by her looks and voice but by her passionate nature. While other little girls played Mummies and Daddies, what Kippe wanted, from an early age, was to play ‘Lovers’ – and ‘what Kippe wanted, Kippe got’.

Not that her parents went in for spoiling. Their rambling, Edwardian house, ‘The Eyrie’, near Radlett in Hertfordshire, had what seemed to Michael countless rooms, and was set in a large garden with a tennis lawn, an orchard and a dovecote. Yet money was always short. Kippe’s mother, Tita, was a large, imposing woman who gave Michael his first inklings ‘of what God might be like’. Before her marriage she had been a Shakespearean actress. She had a voice so deep and tremendous that she was on one occasion invited to read Grieg’s Bergliot over a full orchestra conducted by Sir Henry Wood, and on another given the part of Abraham in a mystery play at the Albert Hall about the sacrifice of Isaac. Her mother, Marie Brema, had been a professional opera singer, the first from England to appear at Bayreuth. She created the role of the angel in the first performance of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, and was once summoned to Buckingham Palace to sing for Queen Victoria. Both mother and daughter were close friends of Bernard Shaw, and when he came to write You Never Can Tell Tita was his model for the feisty and formidable Gloria (‘a mettlesome dominative character,’ in Shaw’s own description, ‘paralysed by the inexperience of her youth’). But neither Tita nor her mother had their heads turned by success. Both were fervent Christian Socialists and most of the money they made on stage was poured into Brema Looms, a workshop providing employment for crippled girls from London’s East End.

In 1906 Tita, who in her late twenties had never so much as kissed a man, had met and fallen in love with a Belgian poet, scholar and nationalist, Emile Cammaerts. There were differences between them. Emile, who had spent much of his youth in an anarchist commune, spoke very little English, and was an atheist. Tita set about tackling both problems with a forcefulness that alarmed Shaw – ‘For Heaven’s sake,’ he warned her, ‘do learn to discriminate between yourself and the Almighty’ – and she succeeded. A Brussels spinster was engaged to teach Emile English (they began their lessons by teasing out Othello, line by line) so that by the time he and Tita were married in 1908 his English was fluent. He had also converted to Christianity with a zeal that would never leave him. As there was little prospect of Tita’s pursuing her stage career in Belgium, and as she felt she must look after her mother, they settled in London, before moving, as their family grew, to Radlett.

Tall, and with a fine, monumental head that would have sat happily amidst the emperors’ busts that ring the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, Emile Cammaerts became revered in academic and literary circles both for his intellect and for his passionate devotion to Belgium. Invalided out of the First World War with a weak heart, he threw his energies instead into composing fiery, defiant, patriotic poems to encourage his compatriots. Lord Curzon translated his work; Elgar set his ‘Carillon’ (‘Sing, Belgians, Sing’) to music. He was Belgium’s Rupert Brooke. When his fourth child’s birth coincided with a significant Belgian victory over the Germans, he named her after the hamlet, De Kippe, where this had taken place.

Emile Cammaerts, 1943.

But while his Belgian patriotism remained central to him – he went on to become Professor of Belgian Studies at the University of London, and was appointed CBE for organising an exhibition of Flemish art at the Royal Academy in 1927 – Emile Cammaerts also, over time, assumed many of the trappings of the English establishment. He was a member of the Athenaeum, a regular writer of letters to The Times, a close friend of G. K. Chesterton and Walter de la Mare, and such a pillar of the Anglican Church that he considered, in his later years, taking Holy Orders. He was widely loved, and on his death in 1953 the Principal of Pusey House in Oxford described him as ‘a man as near sanctity as I have ever met’.

To Michael, as a small boy, Emile Cammaerts seemed ‘all that a grandfather should be’. He had a flowing beard, thick, tweed suits and heavy brown shoes. He emanated jollity. His theme tunes, in Michael’s memories, are Mozart’s horn concertos, to which he would bounce his grandchildren on his knee; and he had about him what his Times obituary would describe as an air of ‘enchanted innocence’. Though he had made his career as an academic, his earliest published works had been plays for children, and he had written a study of nonsense verse. He would delight Michael with recitals of ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’, ‘The Dong with a Luminous Nose’, and, most memorably,

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, ‘It is just as I feared! –

Two Owls and a Hen, four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard!’

Emile Cammaerts’s reputation was considerably greater than his income, and with six children he and Tita were forced to run the household at the Eyrie along strict make-do-and-mend lines. Jeanne remembers Tita’s darning broken bed springs with 15-amp fuse-wire; and avoiding, wherever possible, spending money on clothes, either for herself or for the children. There was principle at play here, as well as economy. Personal vanity was, in Tita’s book, a vice second only to gossip. She had what Jeanne describes as ‘an almost Islamic desire to hide her figure’, and ‘would happily have dressed herself in sacks’.

There was one area in which indulgence was encouraged. The early lives of both Emile and Tita had been bleak. Tita’s father had separated from her mother soon after her birth, abandoning her to a lonely, rootless existence, trailing with her diva mother round the concert halls and opera houses of Europe. Wildly unfaithful, Emile’s father had, similarly, left his mother, just before his birth, and had, finally, shot himself. Both Emile and Tita, as they grew up, had sought security and comfort in beauty – the beauty of the natural world, and the beauty of art.

At the Eyrie they set out to create a home in which their growing brood would be surrounded and sustained by music and painting and books. ‘Every meal,’ Jeanne laughs, ‘was a seminar.’ Even games of rummy and racing demon bristled with moral and intellectual competition. In the red-linoed first-floor nursery, parents and children gathered round a huge black table to read Shakespeare plays – Tita making a memorable Othello. On Sunday mornings, after church, they congregated by an oak chest filled with postcards of religious paintings by Giotto, Leonardo, Fra Angelico. Each in turn, the children were invited to pick out a postcard and to talk about what it told them of the life of Christ.

With such a rich diet of culture, there was little appetite for material comfort. Asked to choose between a new stair carpet and a gramophone recording of Schubert’s trios, Jeanne and her siblings voted unanimously for Schubert.

Sitting in an armchair in an old people’s home in Oxford, Jeanne, now in her late eighties, looks back with gratitude and love on the home that her parents created: ‘They had no model to go on, but they were trying to make a perfect world for us.’ And to some extent, for a while at least, they succeeded.

But, of the six children, the plain living and high thinking at the Eyrie suited Kippe least well. Her gifts were intuitive rather than intellectual, and at St Albans High School, though she shone on the lacrosse field, the teachers made it clear that she was a disappointment after her academic sisters. She was, perhaps, slightly dyslexic. During the family readings of Shakespeare she stumbled over her parts, and this was bitter to her because she had, in fact, a natural feeling for words and characters. The frustration and humiliation she suffered as a result led her to bully her younger, brighter sister, Jeanne.

Kippe went along with the family ethos of goodness and self-denial, but only intermittently. Sometimes she would tell her siblings that she had set her heart on becoming a nurse, and would post her pocket money penny by penny into the church poor-box. Jeanne remembers her reciting with feeling lines from W. H. Davies:

I hear leaves drinking rain;

I hear rich leaves on top

Giving the poor beneath

Drop after drop …

But increasingly Kippe recognised that what she really wanted was to act. She was so taken up with playing parts, in fact, that her sense of self was fragile.

Unlike her mother, moreover, Kippe minded about her appearance and her clothes. She had a natural taste for glamour and flamboyance, which was denied expression; and the passion that had made her such a thrilling playmate as a child proved, as she began to grow up, more dangerous and double-edged. At nineteen, she fell helplessly in love with a Cambridge friend of her elder brother, Francis. At about the same time she had a bad bout of flu. The two things together proved too much for her, and she suffered a breakdown. It was Jeanne who realised first that something was wrong, coming upon Kippe in their shared bedroom fingering a white-painted chair with the tips of her fingers and murmuring, ‘It’s so cold! The snow is deep.’ For nearly three months, Tita and Emile took it in turns to keep a vigil by Kippe’s bedside as she lay tossing and turning, sometimes calling out so loudly that she could be heard by neighbours beyond the Eyrie garden walls.

Looking back, and with the benefit of long hindsight, Jeanne wonders whether Kippe ever properly recovered; but she recovered sufficiently to leave home and return to the stage. After school she had won a place at RADA, and from there she went on to build a successful career in repertory. It was in the middle of a rehearsal in the Odeon Hall, Canterbury, in the autumn of 1938, that a man called Tony Bridge stepped on to the scene.

There was nothing remarkable-seeming about this new recruit to the company. A year older and slightly shorter than Kippe, he was not especially good-looking. Nor was he, in principle, ‘available’. He too had trained at RADA, where he had met and fallen in love with a fellow student, Betty Mallett. Though not formally engaged, he and Betty were regarded, in his words, as a ‘forever’ couple. Yet within weeks of their meeting, Tony and Kippe – or Kate, as he called her, in affectionate reference to her Shrew-ish tendencies – were spending almost all their time together, heading off into the Kent countryside for long walks when they were not required on stage.

Kippe.

In Tony Bridge, Kippe had found a companion of real kindness, a man with what one of his friends later described as an extraordinary gift for ‘ordinary human understanding’. The only child of lower-middle-class Londoners, he had a talent for amusing people, and for lightening and cheering any company in which he found himself. He made Kippe feel safe and happy. A friend, Mary Niven, remembers a joyful evening she spent with the two of them, during which they sang their way through The Magic Flute, Kippe as Papagena, Tony as Tamino: ‘They triggered each other off. They were lost in delight.’

Not everyone shared their delight. Betty Mallett was, of course, devastated; and Tony’s parents, Edith and Arthur Bridge, were disgusted on Betty’s behalf. They did not warm to Kippe, whom they judged flighty and unreliable. Tony, meanwhile, was not all that Tita and Emile Cammaerts had hoped for Kippe. Quiet and unintellectual, he was, on his first visit to the Eyrie, thoroughly overwhelmed by the Cammaerts tribe; and they were underwhelmed by him. His kindness was mistaken for weakness. Kippe, her parents felt, needed somebody stronger.

Both families hoped that circumstances might drive the couple apart. Through the beautiful summer of 1939, their repertory company played to dwindling audiences until, on the outbreak of war, the Odeon Hall was closed. The following spring Tony Bridge was called up, and for the next eighteen months he was shunted from camp to camp around Britain, settling at last in the Scottish coastal town of Montrose. But separation only strengthened the desire for a more formal union, and on 26 June 1941, during a short army leave, Tony and Kippe were married at Christ Church, Radlett. They are captured in a photograph on the steps of the church, Kippe beaming and beautiful in a Pre-Raphaelite dress, Tony in his army battledress and heavy boots, the Cammaerts and Bridge parents flanking them, smiling as the occasion demanded.

Michael’s parents’ wedding, 26 June 1941. Left to right: Arthur and Edith Bridge, Jeanne and Francis Cammaerts, Tony and Kippe, Elizabeth, Tita and Emile Cammaerts.

The smiles are deceptive. On that early summer day, Emile and Tita Cammaerts, at least, were far from happy – and not simply because they had doubts about their future son-in-law. Less than three months earlier they had received the news that their younger son, Pieter, who had joined the RAF early in the war, had been killed, his body cut from the wreckage of a plane near the RAF base at St Eval in Cornwall. His funeral had been held at Christ Church. As his parents posed for Kippe’s wedding photographs, the earth was still fresh on his grave.

Pieter Cammaerts was just twenty-one when he died, and his death cast a long shadow down the years. A difficult, unsettled child, he had followed Kippe to RADA and had proved himself an actor of real talent, leaving in the spring of 1938 with the Shakespeare Schools Prize. At eighty-six, Jeanne still wipes tears from her eyes as she remembers his winning performance as Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing:

Ay, but to die, and go we know not where …

A fable of heroism grew up around Pieter’s last moments. The story that Kippe clung to – that she passed on to Michael, and that Michael has woven into stories of his own – was that the plane in which Pieter was flying as an observer had been damaged during an enemy attack, and the pilot wounded. Seizing the controls, Pieter had insisted that the rest of the crew parachute to safety leaving him to try to land alone. But a visit to the National Archives in Kew suggests that the truth is more prosaic. Sergeant Pieter Emile Gerald Cammaerts, serving with 101 Squadron, took off from RAF St Eval in a Blenheim bomber on the evening of 30 March 1941 on a mission to Brest – a mission that turned out to be fruitless (‘Target area bombed but no results observed’). On return the plane overshot the end of the runway and crashed, killing Pieter and the pilot, and leaving the third member of the crew severely injured.

Pieter’s siblings reacted in very different ways to his death. His elder brother, Francis, who had, at the outbreak of war, registered as a Conscientious Objector, was now moved to join the Special Operations Executive. He went on to become one of its bravest and most remarkable members, decorated with the DSO, Légion d’honneur and Croix de Guerre. But Kippe was too devastated to do anything but weep. ‘She cast herself as Niobe,’ says Jeanne. ‘She was inconsolable.’ For the rest of her life, if Pieter’s name was mentioned, Kippe would walk out of the room; and on Remembrance Sunday every year she would take herself up to her bedroom and perform a private ritual, placing a poppy beside Pieter’s photograph, and reciting Laurence Binyon’s poem ‘For the Fallen’:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn …

With every autumn, the words seemed more poignant.

For Michael, growing up, Pieter was a constant presence. When he visited his grandparents at the Eyrie, he was ‘the elephant in the room’, never mentioned, deeply mourned. And wherever Kippe was, Pieter’s handsome half-profile stared down from the photograph that she kept always on her dressing table. Michael so revered Pieter’s self-sacrifice, and felt so desperately for his mother’s sadness, that he would sometimes find himself weeping for the loss of the uncle he had never known. ‘I think they had been really, really close, my mother and Pieter,’ he says now. ‘I think they had been spiritually close.’

Jeanne is impatient with this notion. She remembers Kippe and Pieter getting on particularly badly, and their shared love of acting being a source of friction rather than a bond. Kippe’s grief, and her retrospective reverence for Pieter, she suggests, had their roots in a melodramatic need ‘to be associated with somebody who had done something splendid in the war’.

There is another possibility. Kippe was stubborn. She had stood firm in the face of her parents’ misgivings about her marriage to Tony Bridge. Yet their future together was fraught with uncertainty. Tony had no money and no home. Once the wedding was over, after a brief honeymoon in the Sussex countryside, he was to return to Scotland, and she to her childhood bedroom at the Eyrie. There was no knowing when the war would end, or when they would be able to live normally as a married couple. Kippe was still only twenty-three and it would be surprising if, in the run-up to the wedding, she had not privately felt extremely anxious. Pieter’s death may have given her just the excuse she needed, consciously or not, to vent her anxiety in grief – just as, in the years to come, it would provide an outlet for the sadness that gathered about her from other sources.

Pieter Cammaerts.

Eleven months after the wedding Kippe gave birth to a son and named him, after his uncle, Pieter. He was, from the start, the spitting image of his father – a father of whom he retains not a single childhood memory. Short leaves were few and brief and by the time Kippe realised that she was expecting a second baby, in the early spring of 1943, Tony Bridge was travelling east, via Basra, to the Iranian city of Abadan, where he had been posted with the Paiforce to guard the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company on the banks of the Shatt al-Arab waterway. It was here that he received a telegram from England announcing that a second son, Michael, had been born on 5 October. It was, he noted in his memoirs, ‘joyous news’.

On the morning of Michael’s birth The Times announced that Corsica had fallen to the French Resistance – the first department of France to be liberated. In the days that followed it became clear that the Allies had the Germans on the run. On 7 October the Red Army mounted a new thrust on enemy positions along the river Dnieper, breaking the Germans’ 1,300-mile defence front; a week later Italy declared war on Germany. By the end of the month the Allies were bombing the Reich from Italian soil. In early December the British government announced that there would only be enough turkeys for one in ten families at Christmas, but any sense of joylessness was eased, on Boxing Day, by the news that the British navy had sunk the last of the great German battleships, the Scharnhorst, off the coast of Norway.

For Kippe, relief that the war might soon be over was mixed with apprehension. Since Tony had left for Abadan she had lived in a state of limbo, real life temporarily suspended. Now she was beset by anxieties. What would her husband do when he came home, and how would he provide for her and the boys? Where would they live? Would the Cammaerts family ever learn to respect him? And, more unsettling, did she respect him herself?

At the Eyrie, childhood rivalries and insecurities had continued to fester, and Tony Bridge had become a source of embarrassment to his young wife. His army career was unspectacular. Flat-footed and rather short-sighted, he had not been commissioned as an infantry officer, and had instead been enlisted into the Pioneer Corps – a blow to Kippe’s pride. His letters home were few and dull, much taken up with complaints about the oppressive Persian heat and his troublesome eczema. Just before Pieter’s death, Kippe’s sister Elizabeth had married an officer serving on the North-West Frontier. Jeanne, meanwhile, was engaged to an officer in the 16th Durham Light Infantry. The letters Elizabeth and Jeanne received were frequent, vivid and entertaining, and they delighted in reading them aloud in the nursery at the Eyrie, reawakening in Kippe the feelings of inadequacy and failure that she had suffered as a child.

Yet all might have been well if, as planned, Tony Bridge had returned home in the summer of 1945. Instead, at short notice, his Iranian posting was prolonged, and just when – as Emile Cammaerts later put it – Kippe was ‘keyed up’ to welcome him back, and ‘worn out by the preparations she had made to receive him and by a series of delays and disappointments’, Jeanne’s fiancé, Geoffrey Lindley, visited the Eyrie with an army friend, Jack Morpurgo.

The visit took place on 27 September 1945, and that morning Michael had spoken his first full sentence. Of Kippe’s first impressions of Jack, there is no record; but nearly half a century on Jack’s memories were vivid. ‘The door opened,’ he wrote, ‘and a girl came in carrying a laden tea-tray. It was unmistakably an entrance; all conversation was silenced, Martha had upstaged a whole cast of Marys; but this Martha had all the advantages … All my attention was centred on that tall slim figure, its every movement a delicious conspiracy between art and nature.’ Here was a treasure, he reflected, ‘who would outshine all else in my collection’.

He knew that she was married, but on the train back to St Pancras that evening Jack Morpurgo comforted himself that ‘a girl as precious as Kippe had no need to waste her loveliness on the Pioneer Corps. “As a golden jewel in a pig’s snout …”’ He was determined, from that first meeting, that he would have her.

Jack Morpurgo had all the qualities that Tony Bridge lacked. He was good-looking, witty, glamorous, faintly rakish. ‘Confidence I never lacked,’ he admits in his 1990 autobiography, Master of None, and self-assurance oozes from his description of himself at the time of his meeting with Kippe: ‘a mature senior officer, his face hardened and blackened by years of sun and wind, his hair already touched with grey, the chest of his uniform-jacket blazoned with medal-ribbons, its epaulets sparkling with rank-badges’.

Born to working-class parents in the East End of London, thoroughly indulged by two adoring elder sisters and precociously clever, Jack had, at thirteen, won a scholarship to Christ’s Hospital, a school founded by Edward VI for poor children. From that moment on, he was relentlessly determined to better himself. ‘I wanted my parents to go,’ he wrote, remembering their delivering him at Christ’s Hospital for the first time. ‘They did not belong in all this spaciousness. They could not match the blatant dignity that surrounded us, already even the elegance of my new uniform set me in another world.’

Jack’s service with the Royal Artillery during the war, in India, the Middle East, Greece and Italy, had stiffened his ruthlessness. He had seen many men die. He had witnessed the defection of wives and girlfriends – including his own great love, Jane, from whose rejection he was still smarting when he met Kippe. He, and those serving with him, had learned that life could be short and uncertain and that they must take what it offered without hesitation or scruple. ‘We were intensely loyal to those who served with us,’ he wrote, ‘but we would not have given a spent shell-case for convention or morality.’ If winning Kippe meant destroying a marriage, breaking the heart of another man, and robbing two infant boys of their father, so be it.

Jack Morpurgo.

In November 1945 Kippe caught the train up to London and she and Jack spent the evening alone together. By the end of the year they were engaged in what Jack later described as a game of ‘Let’s pretend’ – ‘but we were not children, we were in love’.

What happened over the next few weeks can be pieced together from a slim file of correspondence which remains, more than sixty years on, so distressing to Michael that he has never read it in full. Jack Morpurgo was cleverer than Kippe, and he knew it. His letters to her, typed on foolscap in faultless mandarin prose, are exercises in intellectual bullying. He bombards her with arguments until he has her boxed in on every side. Tony Bridge, he insists, is a mere ‘base-wallah’ who has seen no real action. He is utterly undeserving of a wife like Kippe, whom Jack compares to Cleopatra. He flatters Kippe, quoting Keats to Fanny Burney, ‘You have ravished me away by a Power I cannot resist …’, but he also hints that youth is not on her side, and states baldly that he is ‘not prepared to wait indefinitely’. When, briefly, Kippe summons up the strength to break off relations with him, he writes daily to his ‘Lost Darling’, protesting that she has condemned him to ‘an eternity of bleakness’ – yet slipping in a sly reference to Jean Lindsay, a pretty nurse with whom he spent time in Abyssinia, and who has been in touch and wants to see him.

Kippe’s handwritten responses to Jack are, by contrast, short and simple, and filled with self-denigration and remorse. She begs his forgiveness for her ‘failings’ and her ‘selfishness’, for her inability to express herself – ‘it’s pretty poor to be able to say so little so stupidly’ – and to see her way forward. She longs for guidance and comfort. Jack is sparing with his sympathy. ‘You have this marvellous capacity for taking upon your own shoulders the burdens of all the world, and for blaming none but yourself for the mishaps that occur to others,’ he concedes, but he warns that her misery and indecision will be causing damage to Pieter and Michael. And when Kippe admits that, in desperation, she has written a ‘muddled letter’ to Tony Bridge telling him what is afoot, Jack puts her swiftly into checkmate. He and Kippe cannot now stop seeing one another, he argues, because ‘any break in our relations implies acceptance of some guilt, and will imply that to your husband’. Nor can Kippe any longer contemplate a future with Tony Bridge, who, knowing of her feelings for Jack, ‘will pass his days with doubts’.

On receiving Kippe’s ‘muddled letter’ Tony was granted compassionate leave. He made a painful progress back to England – Basra to Baghdad, Baghdad to Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv to Cairo, Cairo to Alexandria, across the Mediterranean to France, and, finally, by steamer into Newhaven. On Friday 1 February 1946 he and Kippe were reunited at the Rembrandt Hotel in Knightsbridge.

They travelled together to Suffolk, and for a week bicycled around Blythburgh, Walberswick, Southwold, Tony hoping that, surrounded by silence and sea breezes, by tall churches, fluent countryside and early spring light, they might somehow recover what they seemed to have lost. They returned to the Eyrie, and for most of that spring they remained together. But the atmosphere was fraught and Kippe was still in touch with Jack. On 4 April, having found Kippe in tears in Tony’s arms, Emile Cammaerts sent Jack a letter, begging him courteously but firmly to leave his daughter alone. ‘I don’t know whether you realize what a terrible strain your present relationship with Catherine imposes upon Tony,’ he wrote. ‘I feel certain that he will not be able to stand it much longer. He is no longer the cheerful and easy-going man we used to know.’ It was no good. Back in London Kippe and Jack went to see a divorce lawyer and, as Jack put it, ‘prepared suitable evidence for inspection by a detective on an appointed day’.

It was to be, by today’s standards, a brutally thorough separation. In the face of fierce opposition from his parents, who were about to lose their only grandchildren, Tony decided that it would be best for his sons if he removed himself completely from their lives. He was, after all, through no fault of his own, a complete stranger to them.

Both sons now speak of his decision with defensive pride: ‘It was,’ says Pieter, ‘a very brave thing for him to do, to give us up. He thought, and I’m sure he was right, that it would be less confusing for us.’ Michael compares Tony to Gabriel Oak – ‘a man who didn’t know the meaning of possessiveness or selfishness’. But Tony did not regard his actions as either brave or noble: ‘It was,’ he wrote towards the end of his life, ‘just the way it had to be.’ After bleak attempts to reignite his acting career in the West End, he emigrated to Canada, changed his name to Tony van Bridge, and eventually found work with Sir Tyrone Guthrie in Stratford, Ontario.

Despite all he had suffered, Tony remained, in a part of himself, devoted to his ‘Kate’. In his 1995 memoir, Also in the Cast, the pages about her glow. ‘I am glad that Kate and I married,’ he insists; and the reader cannot help but feel that the urge to set down those words for posterity was his chief motive in writing the book.

In November 1945, the month that Kippe’s affair with Jack Morpurgo began in earnest, the film Brief Encounter was released in British cinemas. We all know the story: a man and a woman, middle-class, in early middle age and married, meet by chance on a suburban railway station and fall in love. After much humiliation, guilt and anguish – played out against the strains of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 – they agree to part. So compelling were the performances by Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson that rumours flew about that they must genuinely be having an affair. But what impressed the Times critic was not so much the acting as the ‘heroic integrity’ at the centre of the film. In overriding their passions and returning to their dull but dependable spouses, the couple had, in the end, done ‘the right thing’.

All over Britain the opposite was happening. Since the end of the First World War divorce rates had soared. By the middle of the Second World War they seemed to be out of control. In October 1943, the month that Kippe gave birth to Michael, the archbishops of Canterbury and York had spoken out jointly against ‘moral laxity’, urging Christians to remember that promiscuity and adultery were sins that degraded personality, destroyed homes, and visited ‘years of terrible suffering’ on innocent children. But the divorce rates rocketed again that year and the next. In 1945, 15,634 couples divorced; and by the time Kippe and Tony’s decree nisi was granted the following year the number had nearly doubled to 29,829 – a misleadingly low figure, in fact, as by the middle of the year there were more than 50,000 service men and women waiting for divorces, and the Attorney-General had been forced to appoint thirty-five new legal teams to process their cases.

Behind these statistics lay innumerable tales of grief and heartache. Few divorces can have been less acrimonious than Kippe and Tony’s. It was, as Tony later wrote, ‘quiet and unsensational’. But it was, even so, ‘full of suffering on both sides’; and it left Kippe with a burden of guilt that she would carry to the grave.

She had inflicted great pain not just on Tony, whose decency and acquiescence can only have made her feel worse, but also on her parents-in-law. By running off with Jack Morpurgo she had proved all their misgivings about her well-founded, as well as depriving them of access to their only grandchildren. For weeks Arthur and Edith Bridge fought their son’s decision to give Kippe custody of the boys. She cannot have been unaware of their distress.

Then there were her own parents. Both Emile and Tita were children of broken marriages, and both, as a result, had an almost pathological horror of divorce. Ever since his father’s suicide, Emile had been haunted by the notion that there was ‘bad blood’ in the Cammaerts family and that it might one day resurface. On hearing the news that Kippe was to marry Jack, Jeanne remembers, Tita clung to the arms of her chair until her knuckles turned white, while Emile muttered, ‘I’ll kill that boy.’

They pleaded with Kippe to reconsider, employing all the arguments that Emile would later publish in a treatise on marriage, For Better, For Worse: adultery was ‘a sin’; second marriages were ‘sham marriages’; it put a child’s soul in danger to witness ‘division in the very place where union should prevail’. But, as her mind was made up, the chief effect of their pleading was to make Jack Morpurgo determined that they would play very little part in his and Kippe’s future. Though he generally disliked bad language, he referred to Tita simply as ‘the bitch’, and visited the Eyrie as seldom as possible. When he and Kippe finally married, in Kensington Register Office on 16 July 1947, not a single member of the Cammaerts family was present.

Kippe was forced to turn from her own family to the Morpurgos. Shortly after the marriage, she and Jack moved from his flat in Clanricarde Gardens, Notting Hill Gate, to 84 Philbeach Gardens, near Earls Court. The tall, terraced house was somewhat beyond their means, so Jack’s two spinster, schoolmistress sisters, Bess and Julie, moved in with them to help pay the bills and look after the boys. They were to remain a part of the household for the next quarter of a century, a Laurel and Hardy pair – Julie, who had been jilted when she was twenty-one, delicate and emotionally fragile; Bess big-hearted and controlling.

It was Bess who was deputed to take Pieter and Michael for a walk one afternoon, and to explain to them that Jack was now their father. A memory of their conversation remains with Michael, fragmentary but crystal-clear. ‘We were on a railway bridge. I must have said something about my father, and Bess said, “Well, you’ve got a new father now, you know.” And a train came by, and the steam came up in my face. And it just felt quite strange.’

Jack, in fact, never formally adopted Pieter and Michael; but he was determined to expunge the memory of Tony Bridge, and the boys implicitly understood that their real father must not be mentioned. From the summer of 1947 onwards, they took Jack’s surname. ‘No one ever said, “Jack is your stepfather,”’ Michael remembers. ‘And when my mother had two more children, Mark and Kay, no one talked about half-brothers and half-sisters. We were the Morpurgos: that’s what they told the outside world. We children were part of that story; that sham.’

Pieter was just five at the time of the divorce, and had recently learned to write out his full name, PIETER BRIDGE. One of his earliest memories is of being told that he was a Bridge no longer, and of toiling over the new letters M-O-R-P-U-R-G-O. But visitors had only to look at Pieter to see that he was not a Morpurgo. He was extraordinarily like his true father; a constant, vexing reminder to Jack of the man he had wronged. Like Farmer Tregerthen in Michael’s story ‘Gone to Sea’, Jack was ‘not a cruel man by nature, but he did not want to have to be reminded continually of his own inadequacy as a father and as a man’. From the start, he was unreasonably hard on Pieter, whom Jeanne describes as a ‘sensitive, shivering child’, and Michael was aware of being unfairly favoured.

Michael and Pieter outside 84 Philbeach Gardens.

Pieter and Michael, 1948.

Perhaps Kippe, too, was unsettled by Pieter’s likeness to Tony; perhaps, because he was nervous and easily upset, he fuelled her guilt. Michael, by contrast, was a robust, sunny toddler, and with his mother, as with Jack, he had the closest bond. He remembers walking with her, hand-in-hand, through the smog that descended on London like a manifestation of post-war gloom. He remembers the thrill of being allowed to take charge of the ration book when they shopped together at the local International Stores, where he committed his first felony, slipping into his pocket a model Norman soldier with an orange tunic and an irresistible hinged helmet. He remembers stopping with her to talk to the weepy-eyed, skewbald milk-cart horse, Trumpeter, which used to stand shifting from foot to foot in Philbeach Gardens, munching from the sack of hay round his neck, giving off what seemed to Michael a fascinating odour of fur and sweat and dung.

But most vivid of all are his memories of bedtime, when Kippe would sit at the end of his bed and read to him. She read from Aesop’s Fables, Masefield and de la Mare, from Belloc, Longfellow, Lear and Kipling. She had a way of making imaginary characters and places come alive, of conveying the music and joy and taste of language:

Then Kolokolo Bird said, with a mournful cry, ‘Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees …’

Michael rolled the words around on his tongue like sweets. When he was three, his mother found him rocking to and fro in his bed, chanting ‘Zanzibar! Zanzibar! Marzipan! Zanzibar!’

Story-time over, Kippe would leave the door slightly ajar to let in a chink of light. The smell of her face-powder lingered in the room.

Sometimes there could be about Kippe an almost reckless joie de vivre. When one afternoon Pieter and Michael locked themselves into their fifth-floor bedroom while they were supposed to be resting, she shinned undaunted up a drainpipe, ignoring Jack’s protests, and climbed in through their window to rescue them. When visitors came to the house she shone. ‘As she opened the front door,’ Michael remembers, ‘it was as if she was walking on to a stage – beautifully dressed and made-up, charming, sparkling.’

But when the visitors left she tended to collapse, reaching for her cigarettes and smoking almost obsessively. And sometimes for days on end a sadness – what Pieter calls ‘a wondering’ – would settle upon her, and she became quiet and unreachable. Twice a year she would take Pieter and Michael on a bus to Twickenham to visit their paternal grandparents in their neat, modest, semi-detached house in Poulett Gardens. Michael remembers the uncomfortable formality of these visits – ‘the scones, the clinking of spoons on teacups’ – and the awkwardness as the conversation turned to Tony, his grandparents bringing out photographs and press clippings to show to the boys. On the way home, and for days afterwards, Kippe was silent. Michael knew that to ask questions would upset her further, so he too remained silent, aware simply that ‘ours was a family which had at its heart a tension’.

In the wider world, too, he was becoming aware of complexity and shadows. The area around Philbeach Gardens had been heavily bombed in the Blitz, and the house next to number 84 completely destroyed. The cordoned-off bomb site was reachable via the cellar, and Michael particularly liked to play here alone. ‘It was my Wendy house, I suppose. A rather tragic Wendy house.’ Among the weeds and crumbling walls were remnants of life – bits of cutlery, a chair, an iron bedstead – evidence that in the very recent past ‘there had been this terrible trauma’ for the family that had lived there.

Michael, 1948.

School, when it came, confirmed his sense that the world could be harsh. At three, Michael was taken to a playgroup in the hall of St Cuthbert’s, Philbeach Gardens: a cosy, eccentric set-up, where the lady in charge kept order by issuing the children with linoleum ‘islands’ on which they would be asked to sit if they threatened to become unruly. At five, he moved on to the local state primary school, St Matthias, across Warwick Road. It seemed a cavernous, grim place to a small boy, with painted brick walls as in a prison or hospital, and windows so high that if a child tried to look out all he could see were small segments of sky. There was one magical element. Beneath the school lived a community of refugee Greek Orthodox monks: long, black-robed creatures who glided soundlessly in and out of a dark chapel full of glowing lanterns. But within the school itself the children were coaxed into learning through fear. Mistakes were met with a thwack of the teacher’s ruler, either on the palm of the hand, or, more painfully, across the knuckles. Michael found himself frequently standing in the corner. Books and stories were suddenly filled with menace – ‘words were to be spelt, forming sentences and clauses, with punctuation, in neat handwriting and without blotches’. He developed a stutter, his tongue and throat clamping with terror when he was asked to read or recite to the class; and he began to cheat, squinting across to copy from brainy, bespectacled Belinda, who shared his double desk, and with whom he was in love.

So it came as a relief when, just after his seventh birthday, plans were made for Michael to leave St Matthias and join Pieter at his prep school in Sussex. Kippe took him on a bus to Selfridges, and he remembers the delight of being measured up, of being the centre of attention, of watching his ‘amazing’ uniform (green, red and white cap; blazer ‘like the coat of many colours’; rugby boots; shiny, black, lace-up shoes; socks; shorts; shirts and ties) piling up on the counter – ‘all for me!’ He had remained, despite everything, a happy child, ‘very positive, full of laughs, a bit of a show-off’, and the prospect of prep school was thrilling. ‘I was really looking forward to it,’ he says. ‘I had no idea what was in store.’