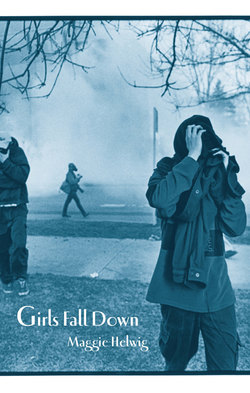

Читать книгу Girls Fall Down - Maggie Helwig - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I

ОглавлениеThe city is a winter city, at its heart. Though the ozone layer is thinning above it, and the summers grow long and fierce, still the city always anticipates winter. Anticipates hardship. In the winter, when it is raw and grey and dim, it is itself most truly.

People come here from summer countries and learn to be winter people. But there are worse fates. That is exactly why many of them come here, because there are far worse fates than winter.

It is a city that burrows, tunnels, turns underground. It has built strata of malls and pathways and inhabited spaces like the layers in an archaeological dig, a body below the earth, flowing with light. People turn to buried places, to successive levels of basements, lowered courtyards, gardens under glass. There are beauties to winter that are unexpected, the silence of snow, the intimacy with which we curl around places of warmth. Even the homeless and the outcasts travel downwards when they can, into the ravines that slice around and under the streets, where the rivers, the Don and the Humber and their tributaries, carve into the heart of the city; they build homes out of tents and slabs of metal siding, decorate them with bicycle wheels and dolls on strings and boxes of discarded books, with ribbons and mittens, and huddle in the cold beside the thin water.

It is hard to imagine this city being damaged by something from the sky. The dangers to this city enter the bloodstream, move through interior channels.

The girl was kneeling by the door of the subway car, a circle of friends surrounding her like birds. Her hands were over her narrow face, she was weeping, and there were angry red welts across her cheeks, white circles around them. Her friends touched her back, her arms, their voices an anxious chirp. There was a puddle of vomit at her feet, and she lowered one hand to wipe her mouth, leaning against the door.

A space had already cleared around them. Some of the passengers in the nearby seats held hands or tissues discreetly over their mouths, but as if this were incidental, as if they weren’t quite aware of anything. As the train rocked through the tunnel, a bubble of light between the dark walls, a few people got to their feet and moved down the car.

The train came into Bloor station and jerked to a stop, and the girl leaned backwards, the pool of vomit spreading, her friends lifting up their feet with little cries. As the door opened, a mass of people on the platform surged forward, then stopped, moved back into the crush and towards another car, their eyes turned politely away.

A grey-haired man in a dark coat stood up and walked to where the girls were standing. ‘Does she have an EpiPen?’ he asked.

‘A what? What’s that?’ A tall girl brushed blonde hair from her eyes. Another girl was hanging on to the metal pole, resting her forehead against it, her red tie hanging straight down, her plaid kilt rolled up at the waist, brushing her thighs. The train wasn’t moving on.

‘An EpiPen. For allergies.’

‘I’m not allergic,’ said the sick girl. The man bent down to look at her rash, keeping a slight distance between them. ‘She smelled something,’ the tall girl said. ‘There’s a gas in the car or something. They should tell somebody.’ She kept talking, but at the same time the PA system gave a quick shriek, and a distorted voice announced that the train was out of service. Beyond the door of the subway car, the crowd began to move like a huge resigned sigh, pushing towards the stairways.

‘They’ll have paramedics here soon,’ said the man. He was about to leave, it seemed, when the dark-haired girl who had been holding on to the pole suddenly swayed and put out one hand, falling to the muddy floor. The other one, the tall blonde, dropped to her knees beside her friend, crying her name.

The man knelt down, frowning. ‘If you want, I could call – ’ ‘Go away,’ whimpered the first girl, dabbing at tears on her welt-covered face. ‘Go away, it’s too awful. It’s not right.’

‘It’s poison,’ cried a girl with curly rust-coloured hair. ‘Somebody put a poison in the train.’

The girl who had just fallen lay with her eyes closed. She too was covered with a rash, but a different one, a red prickly flush all over her face and hands.

‘Someone put a poison gas on the train,’ shouted the tall girl, trying to lift up her friend. The crowd outside the train heard her, and the volume of their voices increased, heads turning, some people stopping where they were. The man held his breath for a second; then, as if seized by an uncontrollable impulse, he sniffed the air, deeply.

‘What was it like, the smell?’ he asked the kneeling girl.

The station was being cleared now, the crowd on the platform fragmenting, breaking into individuals, a blur of brown and beige skin tones, splashes of bright-coloured fabric, patterns and stripes. Announcements were sounding over the PA system, men in uniform appearing, moving people quickly to the exits. A slender woman with plastic bags in her hand stood still and stared at the train, her mouth partly open.

The girl who had fallen was sitting halfway up, clinging again to the pole. ‘Roses,’ she said. ‘It smelled like roses.’

A heavy-set man sat down hard at the top of the stairs, his face suffused with blood, gasping for breath, and a stranger took hold of his arm and pulled him along as far as the fare booth, where he stumbled and fell.

The girl was creeping towards the door of the train, stopping to wipe at the smears of vomit on her legs, and her friend was sitting up, dazed, leaning her head against the tall girl’s chest. On the level above, a woman took off her parka and bundled it underneath the head of the man by the fare booth.

The man in the dark coat started to put a hand out towards one of the girls, and then pulled it back. He looked up and saw the security guards arriving. ‘They’re coming now,’ he said, ‘you’ll be okay,’ and left the train, heading for the stairs. As he went up, the first team of paramedics pushed past him, carrying an orange stretcher, a policewoman watching from the upper level.

‘They smelled a gas,’ someone was saying at the top of the stairs. The paramedics lifted the first girl onto the stretcher. ‘Roses,’ she said.

One of the girls said, ‘Poison,’ again. The woman with the plastic bags was still frozen on the platform. Then she swayed, fell to her knees.

‘Jesus!’ crackled the voice on the PA, someone forgetting he was in front of a live mike. ‘There’s four of them down now. What the hell’s going on here?’

The man at the fare booth told someone that he thought it was his heart, he was pretty sure it was his heart, but when he thought about it he did remember the smell. Yes. The smell of roses.

As more paramedics arrived, a policewoman placed the first call for a hazmat team.

The corridor was narrow and badly lit, the arms of the mall branching off in odd directions, and the stairs were filled now with more police and paramedics coming down, wearing face masks, as the crowd, expelled from the subway, made their way up. No one was paying attention to Alex, as he slid through the turnstile and up the stairs to the mall – and why should they, he was ordinary and forgettable, a thin man who looked much older than thirty-nine, wearing a reasonably good dark coat, his prematurely grey hair cut short. He ducked into the drugstore on his right, hoping it would carry disposable cameras – pieces of shit, they were, he’d never get a decent picture, but at least he’d have a camera-like object in his hands, at least he’d be able to think.

He was not the only person who had broken away from the crowd; in front of him, while he waited at the checkout with a disposable that doubled as a coupon for a Shrek hand puppet, were several people with their arms full of what seemed to be anxiety purchases, vitamin C and ginseng tablets, plastic gloves, antibacterial handwipes. Last year when the buildings fell in New York, in the midst of the aftershock a day or two later, he’d gone into the SuperSave on Bloor and watched people hoarding, all of them apparently unaware of what they were doing – smiling, chatting, walking calmly through the aisles, and at the same time piling their carts full of toilet paper and canned tuna and bags of pasta. Commenting cheerfully on the weather to the sales clerks while stacking up boxes of cheap candles at the cash register. Because you didn’t admit to fear, not up in this country; it would be disruptive and far too personal, and not very nice for everyone around you. He used to consider this an appalling attitude, but lately he thought he was coming to see some virtue in it; the gentle restraint of people who live close together in the cold, and know that they must be patient.

He stepped out onto the seething pavement, between the concrete buttresses of the mall. People were standing at the curb waving for taxis, the line stretching down the block; in front of him at the corner they crowded together, surrounding the hot-dog vendor, covering all of the broad sidewalk and spilling into the street. A city bus arrived, running west, and was surrounded, rushed by a frantic swarm, a few of them making it inside, cramming up against the entryway until the doors groaned closed, and the bus swayed with the weight and set out slowly into the gridlock of taxis on Bloor Street. Another bus was creeping southwards towards them on Yonge – both lines were shut down, then.

He scrambled up against a buttress, bracing one leg at an angle and getting his head above the crush. It was nearly dark. He knew this camera couldn’t really handle the complex light of the swiftly falling evening, but he turned west, tried to frame a shot of the buses, then eastwards, the spire of the Anglican church black against the ink-blue sky and a smoke of charcoal cloud, the line of raised arms hailing taxis down Bloor, an echo of upward movement. Dropping down again, frustrated by the shadows, he slid towards the curb and hopped delicately out into the road, firing shots off quickly in a flurry of car horns as the lights from the stores washed over the traffic, a choppy lake surface. Then, swinging one foot back onto the sidewalk, he realized that the viewfinder was framing the narrow clever face of Adrian Pereira.

‘Hey,’ he said, lowering the camera.

‘Alex Deveney?’

‘Yeah. Adrian.’ He was still standing with one foot in the road, the traffic motionless now. He stepped back up onto the sidewalk. Adrian Pereira, observant and amused, older, his curly black hair thinner, but unmistakably himself. ‘Man, it’s been about a million years.’

‘Give or take.’ Adrian pushed a small pair of wire-rimmed glasses up on his nose. ‘So I hear we’ve had an airborne toxic event.’

‘That’s from a book, right?’

‘Also latterly from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. It’s multivalent.’

‘I was there, actually. I mean, I think I was. I was right by these girls who were fainting, anyway, if that’s what started all this.’

‘Oh yeah? So you’re, like, laden with anthrax spores?’

‘That’s what I figure.’ He wondered if he was handling this properly. If he should say more, or less, shake hands perhaps, or apologize for something. Or say something about those times, when they were young and anxious and the world was wide open. A quick sense memory of smoke and music flickered over him.

‘Seriously, though,’ Adrian looked around, ‘I heard there was a gas on the train. A chemical leak, maybe?’

Alex pushed the disposable camera into his pocket. ‘Honestly, I don’t think so. It just, it didn’t look like that to me. It was a weird set of symptoms, it didn’t look like anything that made sense. And I was right there, it’s not like I’m dropping on the pavement.’ He looked at his wrists. ‘I keep thinking I’m getting a rash, but it’s just a nervous twitch.’

‘You should talk to one of those guys,’ said Adrian, waving his arm at the three ambulances which had now stationed themselves at the corner.

‘I’m not attached to spending a whole night in the hospital so they can tell me I’m fine. I figure I’m being a good citizen by saving them the trouble.’

‘If you say so.’

They wove through the seething stationary traffic, crossing from the northeast corner to the northwest. Alex supposed that he was deciding to walk home; where Adrian was going, he didn’t know.

Adrian pulled his jacket around himself. ‘Do you still see anyone from the paper?’

‘Me? No.’ Alex bent forward under a gust of wind, the sky fully dark now. ‘I’m right out of touch with the world. Are you still playing?’

‘Oh, you know.’ Adrian shrugged. ‘Now and then. Here and there. Mostly teaching guitar to little kiddies, actually. I feel they should have the opportunity to waste their lives in turn.’

‘Hmm.’ Alex saw a mass of people at the next corner, pouring out from the Bay station, waving at the bus as it rocked perilously through the stream of stalled cars. Behind them, the imploring wail of the ambulances.

‘Perhaps you’ve been infected with smallpox,’ suggested Adrian.

‘Yes, very likely. Or maybe the plague. Plague would be good.’

‘I’d take some Tylenol if I were you.’

One of the ambulances had forced itself through the traffic, its blue light splashing against the glass walls of the Gap.

‘I see Suzanne now and then,’ said Adrian.

‘Suzanne.’ No one called her that, back then. Except maybe Alex.

‘Susie-Paul.’

He kept his voice casual, he thought. ‘She’s back in Toronto?’

‘Did she leave?’ Alex stopped walking and stared at Adrian, who put a hand to his forehead. ‘I’m sorry, Alex. Of course she did, I forgot. But yeah, she’s been back a long time. She was wondering if you were still around, actually.’

‘Well, obviously I’m still around. I mean, people can look in the phone book if they’re so damn curious.’

‘I guess that’s true. Nobody thinks of the phone book nowadays, do they? It’s like, that’s a land-based life form, we’ve moved on.’

‘Well. I’m in the phone book, as it happens. Lumbering towards Armageddon.’

‘Yeah, okay, ’cause she might want to know that.’

‘It’s not a question of knowing, is it, it’s like, you open up the book and see it or not. I mean, if you want to know, it’s not like it’s an actual difficulty.’

‘Yeah, okay.’ He nodded towards the corner. ‘I have to go north here.’

‘Oh, well, okay.’ Alex shifted from foot to foot, wondering if he should ask for a phone number, if that would seem too demanding.

‘Good to see you and all.’

‘You too, Alex. Who knows, maybe I’ll see you the next time they poison the subway.’

Adrian turned and started to walk up the street. ‘Hey,’ Alex called suddenly. ‘Hang on a sec?’

‘Yeah?’ He turned again to face Alex.

‘What’s she doing now?’

‘Oh. I don’t know exactly.’ He put his hands in his pockets and shrugged. ‘Something intelligent. You know.’ And then he was gone, into the laneways and expensive boutiques of Yorkville, the crowd swelling on the street behind him.

At Yonge and Bloor, bloated figures in papery white suits crept down the stairs, breathing through masks, holding up instruments with lights and dials. The security guard who remained in the station held a towel across his face as he led the white figures towards the train. Behind smoky glass, another guard sat with his head down, trying to breathe, his hands damp.

Decontamination, said a white figure, its voice obscured by the air filter.

The guard nodded.

What about the girls? said a figure.

Telephone the hospital, said another.

Just precautionary. That’s all. Can’t be too careful.

After the Bloor/Yonge station was cleared at both levels, the trains stopped running north up as far as Eglinton, and south to Union; the eastbound line halted at St. George and the westbound at Broadview. And at every stop along the route the people of the city spilled out, onto subway platforms, into underground walkways and shopping malls, onto the sidewalks and roads, driven upwards into the air. At Queen, as the train pulled into the station, a forty-year-old bass player with thinning red hair, dressed entirely in black leather, was saying to his companion, ‘Drummers. They’re like a different breed, man, eh? Seriously, drummers are a whole different breed.’

‘Yeah,’ said the other man, staring out the window. ‘They’re totally.’

The metallic voice of the PA system interrupted to tell them that the train was terminating, and that they should go to Queen Street to catch a bus northbound. They joined the flow from the train and up the escalator, pausing on the next level. A group of people were gathered at the wall with the map of the PATH system, that complex underground skeleton of corridors and courtyards that could lead them into the malls or the banks, the bus terminal or City Hall, outlining the shape of the downtown core in concrete and tile.

‘It’s like they’re not even the same breed as us, you know?’ said the bass player, as they stepped onto another elevator.

‘Fuckin’ A,’ said his friend.

‘Somebody must of jumped on the tracks, eh? ’Cause it happens like every day, but they don’t admit it. It’s like a public policy they don’t admit it.’

‘Fuckers.’

‘Or it could be one of those, you know, Middle East things, you know, about the war with Iran or whatever.’

‘Iraq,’ said the other man. ‘They’re gonna have a war with Iraq is where.’

‘No,’ said the bass player. ‘No, I gotta tell you, man, I’m pretty sure it’s Iran.’

They stepped out into the chilly evening, the corners of the wide streets filled, the tall glass windows of HMV reflecting the arms of people waving at the buses, pushing for space.

‘You know what, man?’ said the bass player. ‘Screw this, is what. I’m seriously going home.’

Between Broadview and Castle Frank, one train waited, poised on the bridge over the ravine. A man with a briefcase took out a tiny silver phone and sighed impatiently. ‘Yeah, the train’s stuck again … I don’t know … I don’t know … ’ Beside him, a pasty-faced boy in enormous pants stared solemnly at a piece of paper on which he had written the heading RAP SONG, and carefully printed I get more head than King Kong/My style is grim and … He studied the page for a few minutes, changed grim to grem, looked at it for a while longer, and changed it back again. In the seat at right angles to the boy was a couple, probably in their sixties, their faces pouchy and collapsed. The man was very drunk, a smear of alcohol fumes in the air around him, his eyes closed in half-sleep, his head on the woman’s shoulder. She was staring ahead, not smiling, not frowning, blank and still.

Another woman looked out the window, down into the ravine, seeing a red tent half-hidden among the trees at the edge of the twisting river. She spread one hand against the window and watched the rain begin to fall, leaving tiny flaws in the water’s surface, thrumming against the sides of the tent.

Even past Spadina, the traffic seemed locked in a permanent snarl, but when Alex got onto the Bathurst streetcar it was no more crowded than usual. There were no visible effects of the subway incident, but he thought that people did know somehow, fragments and rumours; he was not even sure why he thought this, except for a slight modulation in the atmosphere, a measure of silence, glances of quiet complicity between the Portuguese housewives and the Asian teenagers. He got off the streetcar at College and walked west in the darkness, the rain stinging his face, the fabric of his pants clinging to his knees and calves.

Just past Euclid, a shape moved out of a doorway and into the pool of a streetlight. A man, a big shambling man, with matted red hair and a heavy beard, three layers of ravelling sweaters, his hands shaking, his feet crammed into a pair of women’s fur-lined boots that had split along the seams of the fake leather. ‘Excuse me, sir?’ he said, his voice soft and interrogative, surprisingly high-pitched. ‘Excuse me? I hate to trouble you, sir, but I’m being held hostage by terrorists, would you happen to have any spare change, sir?’

Alex reached into his pocket and found a two-dollar coin, dropped it into the extended hand, a pale mass of flesh, blue veins standing out. ‘Thank you so much, sir,’ said the man, retreating back into the alley. ‘I wouldn’t ask, sir, only I’m being held hostage by terrorists.’

‘Don’t worry about it,’ said Alex.

‘But I’m on cleaning systems now. It’s a lot better since I got on cleaning systems.’

‘That’s good, that’s great. Keep it up.’

One day last month he had been walking in front of the Scott Mission, and two men were standing outside, men with bashed-up swollen faces and rheumy eyes, shouting, ‘No war! No war! Peace for the Middle East!’ He’d wanted to film them, send it to the news, grassroots political initiatives, but what happened at the Scott Mission was in a different dimension, he knew that, a borderline zone whose intersections with the world of agreed reality were tenuous at best.

His apartment was just short of Grace Street, on the third floor, up a narrow flight of stairs; when he moved in, it had been above a cluttered little store selling saucepans and floral-print dresses to middle-aged Italian women, but now the store had been replaced by a café with pine tables and rag-painted walls, and his rent had risen precipitously. It seemed odd to him that he could still afford to live here, but in fact he could – he had a good job, he was a proper adult, there shouldn’t be anything so surprising about that.

He unlocked his door and went in, shouldering off his wet coat. Queen Jane shifted vaguely on the couch and batted her tail a few times, then went back to sleep. He sat down beside her, absently stroking her grey fur and inspecting his feet for any blisters that might be forming.

He took a small fabric case from his coat pocket, opened up his glucometer, unwrapped a sterile needle and looked at his fingers to see if any of them were developing calluses; the right index looked best today, so he pierced it with the needle and squeezed a dark bubble of blood onto the test strip. The sugar count was well within his target range. He slid out a syringe and a little glass bottle of insulin and carefully drew the clear liquid into the barrel, inspecting it for air bubbles, then pulled up his shirt and pressed the needle into the skin of his abdomen. He capped and broke the syringe and went into the kitchen, dropping it into the plastic bucket that he used as a sharps container, opened a tin of lentil soup, sliced a bagel and put it into the toaster.

You would expect yourself to be more curious, he thought, when a thing like this happened. You could speculate, now and then, on just how you’d react to a genuinely important incident, but really what you did, it seemed, was to incorporate it almost instantly into the flow of daily life – the way he had gone on with his routine the day the planes flew into the buildings in New York, the way he had gone from his errand at the bank to his office at the hospital, had spent most of the day at his computer, and forgotten for minutes at a time that anything was wrong. The way you could spend the afternoon in what might perfectly well have been a poison gas attack, check your skin casually for a rash, and not bother with the radio. As long as no one you knew was hurt or sick, you were at least as interested in hearing about a girl you thought you were in love with fifteen years ago.

He wondered if she still called herself Susie-Paul. Probably not. It sounded like she was using Suzanne now. Suzanne Paulina Rae.

He chewed on the bagel and the sharp crumbling cheddar, mopping up the insulin before his blood sugar dropped too low, the intricate dance of chemical balance that he could never ignore, never leave to run automatically as most people did.

There was a photograph he sometimes came across, loose among his files, not properly stored and catalogued like the others because it wasn’t one he’d taken himself. A loose colour print of a dozen people, arranged against the wall of the newspaper office, all of them in their twenties, clear-eyed, effortlessly beautiful. Susie-Paul and Chris were well into the final disintegration of their relationship by then, the paper nearly as far along the road to its own collapse, and the people in the photograph were each in their various ways tense, unhappy, embarrassed. Adrian, who was by no stretch of the imagination a member of staff, had been installed on the sagging couch between Susie and Chris as a kind of human Green Line; he was frowning and adjusting his glasses, one sneakered foot curled up on the cushion beside him. Chris, in a heavy sweater and corduroys, faced the camera down, his face hurt and determined under a forced smile. Susie was looking away, apparently speaking to someone. She was wearing a little flowered sundress over a pair of jeans, and a torn brown leather bomber jacket; her hair, in a feathery bob, was dyed a startling pink, the camera emphasizing her large dark eyes.

Looking out of the frame, he thought. As if there were someone beyond the picture who had a claim on her attention, more than any of the people around her. It had always been that way.

And far over to the other side was Alex, the rarely photographed photographer, a slender young man in black jeans and a black cotton shirt, staring down at the floor, long sand-coloured hair falling over his face like a screen. Adrian probably assumed that Alex and Susie-Paul had been sleeping together when the photo was taken; a number of people believed this, it was one of the generally accepted reasons for Chris and Susie’s rather noisy and public breakup and the subsequent failure of the paper. Alex couldn’t remember now who had taken that picture – it didn’t look like a professional shot – but whoever it was, they or the camera had been more perceptive, had understood that Alex’s real position was then, as ever, at the margin, a half-observed watcher of the greater dramas.

I don’t know, said the girl, lying on a cot in the hospital, her legs covered with a sheet. I don’t know. I can’t tell you. I don’t know.

They had been doing nothing, her friends said, talking to the doctors in the hallway. They went to Starbucks. They walked in the park. They got on the subway and then she said she was sick, and they thought maybe there was a funny smell, and she said yes, there was this rose kind of smell, but she was too sick to tell them much, and then the other one fell down as well, and they could all smell it now, and somebody ought to do something because it totally wasn’t right.

The white figures bent to the floor of the subway car, their heads lowered, their eyes intent behind the masks. They searched for traces of liquid or powder, greasy smears; they collected old newspapers and food wrappers and sealed them into plastic containers. The instruments registered no danger. The tests they could perform in the small metal space of the car told them of nothing, of absence. They would take their sealed containers to a secure lab for further testing. The girls in the hospital watched their blood flow into tubes that would be carried to another specialized facility, but the blood would say the same thing, it would say that it could tell them nothing.

The rain was turning into a light icy snowfall now – not too bad, not impossible weather to work in. For a minute Alex leaned back against the wall, letting his eyes adjust to the darkness before he walked to the streetcar stop.

He did not admit to urgency. He did not admit to himself that missing even a single night bothered him, that this was becoming compulsive. He had always worked on his own projects in his free time, legitimate creative projects that were exhibited and published here and there, and he would not grant that he was behaving differently now.

He took his Nikon with him, and a shoulder bag with lenses and rolls of film. The digital technology was getting very good, he could see why a lot of people had made the shift, but he still preferred film for his own work, still liked the darkroom process, the smell of chemicals and craftwork on his hands. The Nikon was his standard personal camera. There was also the old Leica, but that was special – it was quirky, felt somehow intimate and tactile. There was a particular kind of photography that needed the Leica; he didn’t use it very often.

He had always done this. Maybe not every night. It was true that he spent more time on it now. He’d broken up a while ago with Kim, a graphic designer he’d been seeing in a rather desultory fashion anyway. Sometimes the people in the imaging and computer departments of the hospital went out together, but missing these occasions seemed like no great loss.

Instead he wandered – down to the junkies and evangelists of Regent Park, or up the silent undulating hills of Rosedale, taking pictures by the pale light laid down from the windows of the mansions. Through dangerous highway underpasses to the lake, slick shimmering water rasping on the shores by deserted factories. To the bus station, the railway station, the suburban malls where his footsteps echoed by shuttered stores in the evening.

Tonight, perhaps because he’d been thinking about Susie-Paul and the paper, he went only as far as the university, got off the streetcar at St. George and started walking north. It seemed surprisingly quiet, the broad pavements almost empty. Maybe the students left the campus in the evenings. Or maybe students these days didn’t go out, maybe they stayed in their rooms and read books about management techniques – but he was showing his age, one of those old people who no longer complained that students were too wild, but that they were too good, they ate right and married young.

Susie had been his grand passion, he supposed. The phrase amused him. A grand passion. Everybody needed one. Not the most serious relationship necessarily, or the most real – that was surely Amy, who had lived with him, who he might almost have married – but the one that burned you out, broke you to pieces for a while. At some point in your life before you were thirty, you needed to be able to listen to ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ and cry real tears.

Outside the Robarts Library, he took a picture of a nervous girl buying french fries from a cart, then stepped back and shot a series of faint human figures, hurrying under the brutalist concrete shoulders of the massive building, blurred by the tall lights and the faint haze of snow. The wind whipped his scarf across his face as he walked up the broad curve of the stairway. He pushed open the glass door and went into the library’s forced-air warmth. He was pretty sure he wasn’t supposed to take pictures here, but he usually managed a few, inconspicuously. A row of students awkwardly curled up asleep in the chairs; an elderly man in rubber boots, puddles around his feet, reading one magazine after another.

He left the library and kept walking, east past the darkness in Queen’s Park, statues and whispering men among the trees, then the cheap bright flare of Yonge Street, ADULT DANCERS and VIdEOS HAfL-PRiC, the neon signs reflecting in nearby windows like flame.

The white figures rose up from the station, the air judged innocent, uncontaminated, to the extent that the instruments could detect.

This is the nature of safety in the measured world – you can be certain of the presence of danger, but you can never guarantee its absence. No measurement quite trusts itself down to zero, down to absolute lack. All that the dials and lights and delicate reactions can tell you is that the instruments recognize no peril. You can be reassured by this, or not, as you choose.

It was later on that night, and Alex had come home, packed away his film and lenses. He was in the kitchen reaching for a jar of peanut butter, not thinking about anything in particular, when he caught himself blinking.

There was something in his field of vision.

He blinked again, and it didn’t go away. He shook his head quickly, knowing this was useless. No change. Tiny black spots, just two or three. Up a bit and to the right. He closed his right eye, leaning against the counter. Standing in the empty kitchen, listening to the sound of his heart.