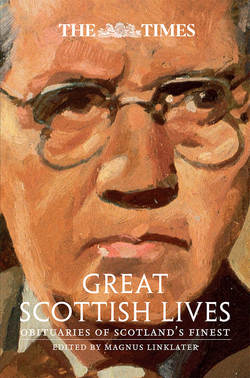

Читать книгу The Times Great Scottish Lives: Obituaries of Scotland’s Finest - Magnus Linklater, Magnus Linklater - Страница 6

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Magnus Linklater

From Sir Walter Scott in the nineteenth century to Tam Dalyell in the twenty-first, this collection of obituaries from The Times is a 200-year chronicle of great lives that have left their mark on the history and character of the Scottish nation. Politicians, artists, inventors, explorers, soldiers, academics, philosophers and troublemakers – these are men and women who have, in their different ways, broken the mould of their time, challenged its conventions and occasionally outraged them.

They cover a period that ranges from the age of the Enlightenment to the post devolution era – the building of empire, the industrial revolution, through two world wars and the economic chaos between them – culminating in the creation of a new Scottish Parliament and the legacy it has fashioned. Through all of these, Scots were often at the centre of great events, and their obituaries are, to an extent, a commentary on the times in which they lived.

This volume should not be read as a coherent history, nor is it necessarily a carefully balanced selection. These are lives judged, not from the vantage point of our time, but from the standpoint of their own time. That is its merit, and occasionally its idiosyncrasy. Great figures who seem to us now to loom large are sometimes dismissed with little more than a footnote; others are accorded page upon page of eulogy, which may seem, in the modern era, excessive. It is striking, for instance, that the Scottish colourists – artists like Peploe, Cadell or Fergusson, to say nothing of the designer and architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, whose work is so valued today – were viewed by The Times, on their deaths, as worthy of only a few sketchy paragraphs. That may reflect a London perspective, but more likely the fact that their reputations have grown more in the last 50 years than during their own lifetimes. Statesmen and prime ministers, on the other hand, are chronicled with a depth of detail that amount almost to a political history of the age in which they lived.

There has had to be some editing. The death of the writer and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, for instance, prompted an obituary in The Times of more than 9,000 words, amounting almost to a full-scale critical biography. Those were the days when long columns of small print, uninterrupted by pictures, were routine. Running Carlyle’s obituary at full length – to say nothing of others which frequently amounted to 5,000 words or more – would have required a volume three times the size of this one. Instead I have tried to keep the flavour of the tributes paid, rather than including every last paragraph.

There has had to be selection, of course, and I am open to criticism for the lives that have been omitted. Legitimate questions will be asked about why there is no mention here of the writer Lewis Grassic Gibbon, whose Sunset Song is on every respectable reading list; Walter Elliot, who created the modern Scottish Office; Sir William Lithgow, last of the great shipbuilders; the debonair Hollywood actor David Niven; Ewan MacColl, pioneering folksinger; the ballet director Kenneth Macmillan; the iconoclast journalist Sir John Junor – the list goes on.

There are two explanations. The first is that this is not, and was never intended as, a definitive collection; great Scottish lives have been well documented elsewhere in encyclopedias and biographies, researched, brought up to date, and accorded their proper place in history; a collect-ion of contemporary obituaries makes no claim to replace them. The second is that, where there is a judgment to be made, I have favoured the well-written and the colourful over the dutiful and the worthy. Thus the Marquis of Queensberry – “a man of strong character, but unfortunately also of ill-balanced mind” – is included, not just because he formulated the Queensberry rules of boxing, but because the obituary itself is an entertaining account of an eccentric character, and, to an extent, a commentary on the society of his day. The life of Sir Colin Campbell – he of the “thin red line” at Balaclava – is a remarkable narrative of military exploits, but is also invested with an eloquence which is very much of its time. Thus: “he did not conceal his ill opinion of the Indian army, and considered the Sepoys as the mere bamboo of the lance, which was valueless unless it were tipped with the steel of British infantry.”

The remarkable pioneer of nursing medicine Dr Elsie Inglis is lovingly described: “Her splendid organising capacity, her skill, and her absolute disregard of her own comfort … drew forth the love and admiration of the whole Serbian people, which they were not slow to express.”

I favoured the Labour rebel James Maxton, “tall, spare, pale, and almost cadaverous-looking, with piercing eyes and long black hair, a lock of which fell at emotional moments over the right ear …” as well as Bill Shankly, the football manager, an “old-fashioned half-back [who] was said to have run with his palms turned out like a sailing ship striving for extra help from the wind.”

No one could argue that the Russian-Scottish writer Eugenie Fraser changed history, but who, on the other hand, could resist an obituary that begins: “Ninety-six years ago, a baby girl, half Scottish, half Russian, wrapped in furs against the bitter cold of an Archangel winter, was taken by sledge across the River Dvina to the house of a very old lady [who] had lived long enough to remember seeing Napoleon’s troops fleeing down the roads of Smolensk and to have had a son killed in the Crimean War.”

There are too few women here, again a reflection of the age in which these obituaries were compiled; but those who are included are memorable: Katharine, Duchess of Atholl, the “red” duchess, and one of the first women to hold ministerial office: a “tiny, upright, hawk-like figure … poised with an innate dignity that was reinforced by the greatness of her moral stature.” Mary Somerville, the first woman controller at the BBC, of whom her obituarist wrote: “When troubles arose, no staff were ever better defended in public, though in private they were often told pretty frankly where their work had fallen short.” Or Margo MacDonald, the SNP’s “blonde bombshell,” who once said: “I don’t choose my enemies; they choose me.”

Times obituaries have always been anonymous – and remain so today – an important tradition which allows judgment to be made about a subject’s character without the accusation that the writer’s personal prejudices are being deployed. Whoever it was who wrote of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman that “it is impossible for the impartial historian not to blame [him] both for the unwisdom of his initial policy [on South Africa], and for the costly injudiciousness of some of his phrases” was able to do so without risking a lengthy correspondence on the objectivity of the writer – or lack of it. Behind each obituary lies the opinion of The Times rather than the individual.

Overall, however, the impression that emerges from this pantheon of Scottish characters is one of the rich contribution they made to human society. Those who wished to undermine it are greatly outnumbered by those who reinforced it – the bridge-builders, the architects of civic programmes, the great military commanders, the explorers and the inventors, many of whom made robust comments on the world in which they lived. Alexander Graham Bell, for instance, was scathing about government interference in the commercial exploitation of the telephone which he had invented: “I am afraid that the comparatively low state of efficiency in this country [the UK] as compared with our system in the United States must be attributed to Government ownership. Government ownership aims at cheapness, and cheapness does not necessarily mean efficiency.” His comments are as relevant today as they were then.

Here then is a cross-section of history, told by those who are offering a contemporary view of its most significant characters. However far in advance of their demise these accounts may have been composed, there is a frankness of view which rarely emerges from more considered opinions; and where that view is warmly admiring, then the expression of it comes across with an immediacy which is refreshing.

The death of Sir Walter Scott, the first name to appear here, provoked an outburst of affection which comes down to us across the years, its spontaneity undiminished by time:

“Of a man so universally known and admired, of a writer, who by works of imagination, both in prose and verse, has added so much to the stores of intellectual instruction and delight − of an author who, in his own time, has compelled, by the force of his genius, and the extent of his literary benefactions, a unanimity of grateful applause which generally only death (the destroyer of envy) can ensure – it would be superfluous, and perhaps impertinent in us, to speak …”

It is often said that journalism is the first draft of history. If that is the case, then surely the obituary is the first sketch of those who shaped it.