Читать книгу Ben Barka Lane - Mahmoud Saeed - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеchapter 1

The vacation is defined in my mind by an event that seems at the very least more important than the usual. During the days of that tense summer I spent in Mohammediya (Fadala) in 1965, the weavings of chance made me feel I was confronting the experience of a lifetime, the excitement every young man pictures in his dreams.

A year before, I had found an apartment in a building of three floors belonging to a Chinaman. It was pretty and pleasant, and blessed by the warm rays of the sun at about twelve o’clock, after the last fragments of the midday call to prayer rasped from some worn-out throat. The sound was not far away, as it came from the Casbah, behind its wall of reinforced brick. Storms had played havoc with the wall, turning its strength and form into red earth, constantly eroded. That had brought those responsible for monuments to think about protecting it, for fear that it might collapse and leave only the Casbah Gate, that exemplary historical monument, to bear witness to the grandeur of an ancient edifice adorned by rare arabesque designs.

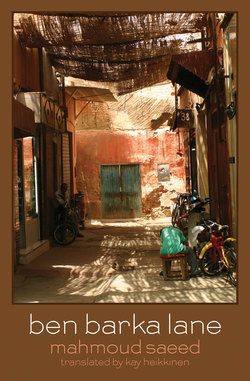

The building belonging to the Chinaman, M. Bourget (who had confused me at first by his multiple names and his origin), stood at the head of Zuhur Street, as Si Sabir calls it, or Ben Barka Lane, as al-Qadiri calls it. It is a street that divides the small city in two, beginning from the Bab al-Tarikh Square and ending in the new port and the fish market, passing by the most important and beautiful features of the city—the lovers’ garden, the nature walk, the large casino, and the Miramar Hotel—until it nears its end and the space is allotted on every side to the Samir petroleum refinery, to canning and printing plants, and to the unending farms stretching left and right, until the city ends at the rocky sea shore, on which one looks down from a great height. The lethal rocks had once brought a Spanish steamer to grief by night, destroying everyone in it and leaving only a small part of the frame, rusting and still bathed by the ocean waves.

A Bata shoe store shines on the ground floor of the building with its refinement, its gleaming glass and modern décor. Across from it is a row of modern, elegant shops: a bakery that made my mouth water over its delicious displays every morning, a store selling stamps, another selling lottery tickets, a butcher, a brasserie serving everything from bottles of soda to various kinds of drinks, then the largest store, for luxury goods and furniture, belonging to Si l-Wakil and his brother, and another brasserie.

At the head of the street the new city begins, splitting offrom the old Casbah, proud of its radiant youth and smiling at the future, after the last vestiges of domination had disappeared and the French would no longer burn alive any Moroccan they found wandering in their streets after dark. This city embraced the newcomer as soon as he stepped of the bus from Rabat or Casablanca.

More than anything else, my heart was gladdened by the presence of a busy coffee shop, where grains of idle time dissolved in a singular haze of pleasure, melting in the aroma of fine black coffee and visions of the past and of time yet to come.

From the first moment, I fell in love with this unique apartment, its floor a single expanse of gray and soft yellow mosaic, rising on the walls in every direction to the height of a yard, attempting to rival the colored arabesque tiles rising to about the same height on the walls of the Casbah. What more could I ask for? Could the stranger ask for more than to find everything he needs no more than ten steps away, from the bar to the butcher? After twenty-five years of deprivation, persecution, hardship, political struggle, prison, dismissal, and unemployment, I felt as if I had stumbled on a paradise that Adam himself would envy.

What attracted me to this spot was its peacefulness, as well as its beauty and its history, but also the pigeons which clustered in flocks near the wall and its gate. They paced serenely and securely, delving in the cracks of the ancient brick for some stray seed, from time to time fluttering over each other, descending calmly or rising noisily, at times bestowing on the observer a pleasure akin to the early, eternal pleasures of sex.

When I gaze in the afternoon to where the sun immolates itself in a strange calm over the sea hidden from my sight, I feel a strong longing for something I dream of without attaining, wrapped in a captivating, wine-like pleasure flowing through my body and numbing my limbs. I am barely aware of anything in my surroundings until the sudden, daily reversal occurs, and all at once I find myself in a light gray darkness which pushes me with gentle fingers stroking my back, driving me to where I can find all the small pleasures I dreamed of. Others might consider them trifling, but in my particular situation they are enough to justiffy a happy life.

The Chinaman lived in the adjacent building, on the other street, which formed the second side of the equilateral triangle, in which Bata represented the main angle, across from Bab alTarikh. He rented the rest of it to a Jewish tailor and peddler, and to a few French and other foreigners.

One warm, sunny morning at the end of April, Si Ibrahim motioned to me, so I crossed the street. Si l-Wakil caught me and asked me to please take a rare stamp to Si Sabir. Si Ibrahim spoke to me, proudly raising a box of strawberries in his hand:

“Do you plant them in your country?” “No.”

“A private farm ripened them three months before their time.”

“ What are they called in Arabic?”

He began to look for the Arabic word, and I thought his head would explode before he found it, so I said first:

“Shaliik.”

He nodded his head as he repeated: “Shaliik.”

“Put them on my account.”

I was on my way to the school. It was a vacation day, and the guard at the end of the hall raised his right hand in greeting and picked up the broom with his left.

I saw no one but Si Sabir. I held out the strawberries. “I brought you breakfast.”

He laughed. “How much did you drink last night?”

I put the small box on the table. The red heads of the berries glowed enticingly.

“Please have some, Si.”

But he stood back and said, “First, let me present to you… Si l-Habib.”

I was surprised to see the man, sitting calmly of to one side, and looking at me searchingly. I shook his hand. He got up a little and bowed.

Si Sabir threw away his cigarette and took one of the strawberries with the tips of his fingers. I urged Si l-Habib. He took one, and I burst out: “One isn’t enough. Have more.”

Si l-Habib had been forced to stay in Mohammediya after the stormy events that had crushed the country at the beginning of the ‘60s. He had been fleeing to the east when he was arrested. All that saved him from the noose was a severe heart attack that flattened him for a long time, leaving him suspended between life and death in the prison hospital, in the care of doctors and nurses who hid their sympathy behind the frowning mask of someone doing a duty. When the crisis ended he was encompassed in the supreme neglect of the authorities. Afterwards he played the game of living with a weakened heart, under strict orders that warned him away from any exertion or activity or shock that could lead to his death. His illness cut the hangman’s noose but left him in bitter banishment from activities he believed he was made for, without which his life was no more than death itself in slow motion.

The arduous struggle against the French before independence, and against apathy and internecine feuding afterwards, had tempered him, bringing him to a degree of glory reached by only a few notable personalities in a few countries.

As Si Sabir said, “Politics is like commerce in a free country: it chokes the children it has created.” But I was always thinking of the feelings of those who had attained tremendous heights in their past and had fallen from them obscurely and suddenly. What was the true nature of their feelings? Did any of them dream of returning to the dais of true glory, untouched by troubles or falsity? With respect to Si l-Habib in particular, I wondered, as I watched him pick another strawberry from the box, if his weak heart could bear the surprise of a happy moment.

He was confined to Mohammediya in compulsory residence. Had he been allowed to choose the place? I did not ask. All the coastal cities are surpassingly beautiful. Yet I knew he loved Mohammediya, preferring its old name of Fadala, the hidden pearl of the coast whose value had been discovered more than half a century earlier by people from all over the wide world. Still, even in his state of compulsory fixed residence and exclusion from politics, he was unable to keep from commenting sharply when he saw the lofty castles of the great side by side with the huts of the wretched.

In a time of trial he had endured when he was on top, he had been tempted by the idea of possessing a home in any area he might choose for himself, through the application of a law compensating the most important fighters in the struggle against the French. But he stood with Si Bayad Ben Bella and the councilor against it, so the law was buried alive, mourned by many honorable men who considered it a pension for their children in an uncertain world, and equally by a large number of time servers and opportunists.

Si l-Habib would say that he felt the whole city —Fadala —was his home, for the eternal green of this small spot refreshed the heart. It traced with a graceful hand dreamlike walkways that took the breath away, and small, gaudy asphalt passages that, between one stroll and the next, would break forth in cascades of flowers, crimson, violet, and yellow, making the city a checkerboard of unhedged gardens and small forests that embraced the paths at every turn.

At dawn the city was plunged in a fog that was soon scattered away by the rays of the sun, which turned it into a gentle mist. It moistened everything, and on the leaves of the trees it left drops like shining tears.

Si Sabir’s room was the school’s library and business office. It was a large room, its shelves choked with thousands of books. The white windows to the west were open on a peaceful morning, perfumed by the aroma of climbing flowers that danced with each playful touch of air.

I looked searchingly at Si l-Habib. His dark, handsome face had a fine Arab-Roman contour of which he seemed completely unaware. His large black eyes shone with a sweet, childlike luster, unsullied by the disputes of political life, deceiving the onlooker with an endless simplicity. But I noticed, behind the thick black hair hanging down over his forehead, the traces of wounds that had healed over and were now barely apparent.

I spoke with Si Sabir for a few minutes about school matters, all the while aware of the presence of Si l-Habib, the first person I had ever encountered who had achieved such fame and universal respect. I suppressed my feelings—attraction to him and my growing affection—but I was like a closed pot that prevents hot steam from escaping, and finally they blazed up. I blurted out, “How I have longed to meet you!”

He laughed and took another strawberr y. His childlike smile beamed again. This was the source of his attraction. No one estimating his age could give the true number! Forty? Thirty-eight? At twenty-five, I probably looked older than he did in his forties. What was the origin of this impression of youthfulness? Was it innocence?

“Really?” Uncertainty and disbelief appeared in his smile. “Yes. That is how I felt. And more.”

“More? Does that mean you were afraid to meet me?”

Si Sabir broke in heartily. “He? Fear? He’s exactly like you.”

I said quickly, “No, I’m not like you. I was a soldier, not a commander.”

He shrugged his shoulders. “Soldier or commander…. There’s no difference between them in an unequal battle.” Then he looked at me searchingly. “Are you being attracted by defeat?”

I repeated, bewildered: “Attracted by defeat?”

“I’m afraid that what attracted you to me is your feeling that we are both in the same defeated camp.”

“Does that matter?”

He nodded his head. “Yes. Feelings alone are not enough to build a relationship on a solid foundation.”

Si Sabir interrupted, pointing to me: “Two things are never far from him: sex and politics.” He followed his words with the wise nod of his head that he often used to underscore his state-ments, and added, “But in his country he only had politics.That ’s what confuses the picture.”

Si l-Habib asked, “Then how can you look forward to the future there?”

“ What does sex have to do with that?”

“A man doesn’t walk with one leg.”

Si Sabir burst out laughing, and added: “I’ve told you more than once, you can’t work when you’re hungry!”

Si l-Habib said, looking at me warningly, “They detained a lot of easterners last year.”

Si Sabir added, “Yes—in the events of Casablanca, in ‘64.” I smiled. “But they released them within days—didn’t they?”

Si l-Habib just laughed, but Si Sabir said: “Detention is easy. What ’s disastrous is kidnapping—and assassination.”

We finished the strawberries. The fruit was sticky, and I went out to wash my hands. I had often talked with Si Sabir, who was a drinking companion, about the secrets of my empty life, and he must have told Si l-Habib something about me, for when I returned he was looking at me serenely with affection and understanding.

I have never in my life seen anything more beautiful, serene or understanding than his way of looking at one. His eyes drew a loving circle overflowing with truth and afection. I was in the middle of it. There was no need to speak; a strong bond had been created between us, an openness that removed all the chains that can shackle relationships between men. His way of looking radiated distinction in a way that raised me to his level, whence I looked down from the top of a wall on all the secrets of the past and present, becoming an equal partner in the destiny of peers.

I cannot describe how happy I was to meet him. He came into my life like a precise, modern, and comprehensive dictionary of everything relating to exploitation and colonialism, of the past of the Moroccan people, of their tribal and historical makeup and the aspirations that now began to be revealed to me.

Si l-Habib lived in one of the only two apartments on the ground floor of my building; I had seen him often, but he had avoided meeting my eyes, which killed the urge to give him the customary greeting. Nor was I tempted to look inside his store, which was located at the end of the shops on the same floor, though I had seen him sitting there, hidden by a window filled with a display of kitchenware.

Over our beers before lunch at the Maliki Hotel, my glance moved between the tired eyes of Si Sabir and the mature French barmaid, who at fifty refused to admit the defeat of her youth, retaining a wealth of attractiveness created by muted, sensitive adornment. Si Sabir told me more about Si l-Habib. What most worried Si l-Habib, he said, was the family of Si Bayad Ben Bella, his friend who had been martyred, leaving a daughter, Zahra, in her third year of high school—a young woman who was characterized by intelligence and courtesy.

During the three months following our first meeting, a quiet, strong friendship grew between me and Si l-Habib, transforming a small seed into a towering tree, growing quietly but confidently. There were no longer any days when I didn’t see him. That meeting of ours in the library became a defining date for me, leaving everything before it enveloped in fog, while light and music enfolded what followed it.