Читать книгу The Spectacle of Disintegration - Маккензи Уорк - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 The Critique of Everyday Life

What good is knowledge if it isn’t practiced? These days real knowledge lies in knowing how to live.

Baltasar Gracián

Henri Lefebvre started this line of thought with his 1947 book The Critique of Everyday Life Volume 1 and raised it to a fine pitch with that book’s second volume in 1961. But the group who really pushed it to its limit was the Situationist International, a movement which lasted from 1957 until 1972, and which its leading light Guy Debord would later describe as “this obscure conspiracy of limitless demands.”1

While their project was one of “leaving the twentieth century,” in the twenty-first century they have become something of an intellectual curio.2 They stand in for all that up-to-date intellectual types think they have outgrown, and yet somehow the Situationists refuse to be left behind. They keep coming back as the bad conscience of the worlds of writing, art, cinema and architecture that claim the glamour of critical friction yet lack the nerve to actually rub it in. Now that critical theory has become hypocritical theory, the Situationist International keeps washing up on these shores like shipwrecked luggage. Are the Situationists derided so much because they were wrong or because they are right?

Consider how their legacy is isolated and managed. The early phase of the Situationist project, roughly from 1957 to 1961, is safety consigned to the world of art and architecture. Its leading lights, such as Pinot Gallizio, Asger Jorn, Michèle Bernstein and Constant Nieuwenhuys, all have books and articles dedicated to managing their memory.3 The period from 1961 to 1972 is considered the political phase, and its memory is kept by various leftist sects who reprint the writings of Raoul Vaneigem, Guy Debord and René Viénet, and are mostly concerned with the critique of each other.4 Of more interest to us now perhaps is Post-Situationist literature, in which former members or associates, including T. J. Clark, Gianfranco Sanguinetti and Alice Becker-Ho, restate or revise the theses of the movement, which runs more or less from 1972 to Debord’s death in 1994.

The life and work of Guy Debord, the one consistent presence in the movement, is fodder for all kinds of recuperations. For biographers he is a grand grotesque, or a revolutionary idol, the hipster’s Che Guevara. Certain enterprising critics have turned him into a master of French prose.5 By recuperating fragments of the Situationist project within the intellectual division of labor, its bracing critique of everyday life as a totality, not to mention the project of constructing an alternative, tends to disappear into the footnotes.

In 2009 the French Minister of Culture, Christine Albanel, declared the archive of Guy Debord a national treasure. The archive, in the possession of Debord’s widow, Alice Becker-Ho, contains a holograph of Society of the Spectacle, reading notes, notebooks in which Debord recorded his dreams, his entire correspondence, and the manuscript of a last, unfinished book, previously believed to have been destroyed. Yale University had already expressed interest in acquiring the archive, prompting the Bibliothèque Nationale, or French National Library, to make securing the Debord archive a priority.

The fund-raising arm of the Library holds an annual gala dinner to hit up its big benefactors for cash, and its 2009 event displayed Debord notebooks to tempt donors. Present were several board members, including Pierre Bergé (co-founder of Yves Saint Laurent) and Nahed Ojjeh (widow of the arms dealer Akram Ojjeh). Only E180,000 was raised, a fraction of what the Library had to find for Becker-Ho. “This evening depends upon the spectacular society,” fund-raising chief Jean-Claude Meyer admitted in his speech. “It’s ironic and, at the same time, a great homage.” But if the Library could make an archive out of the Marquis de Sade, then anything is possible. The gala dinner took place in the Library’s Hall of Globes, a monument to the presidency of François Mitterrand, who Debord particularly detested.6

The gulf that separates the present times from the time of the Situationist International passes through that troubled legacy of the failed revolution of 1968 and 1969 in France and Italy, in which Situationists were direct participants. There was no beach beneath the street. Whether such a revolution was possible or even desirable at that moment is a question best left aside. The installation of necessity as desire in the disintegrating spectacle is a consequence of a revolution that either could not or would not take place.

Even if a revolution could not take place in the late twentieth century, in the early twenty-first century it seems simply unimaginable.7 It is hard not to suspect that the over-developed world has simply become untenable, and yet it is incapable of proposing any alternative to itself but more of the same. These are times in which the famous slogan from ’68—“be realistic, demand the impossible”—does indeed seem more realist than surrealist.

And yet these are times with a very uneasy relation to the legacy of such intellectual realists. Debord in particular is at once slighted and envied, as he was even in his own time. He was, by his own admission, “a remarkable example of what this era did not want.”8 He seemed to live a rather charmed life while doing nothing to deserve it. Debord: “I do not know why I am called ‘a third rate Mephistopheles’ by people who are incapable of figuring out that they have been serving a third rate society and have received in return third rate rewards … Or is it perhaps precisely because of that they say such things?”9

Not the least problem with Debord is that of all the adjutants of 1968 he was the one who compromised least on the ambitions of that moment in his later life. “So I have had the pleasures of exile as others have had the pains of submission.”10 Unlike Daniel “Danny the Red” Cohn-Bendit, he did not become a member of the European Parliament. As Debord wrote in 1985, looking back on the life and times of the Situationists: “It is beautiful to contribute to the ruination of this world. What other success did we have?” The key to the Situationist project of transforming everyday life is the injunction “to be at war with the whole world lightheartedly.”11 This unlikely conjuncture of levity with lucidity, of élan with totality, has rarely been matched.

It’s not as if there aren’t enough studies of the Situationist International and its epigones. While written in another context, these lines from Becker-Ho seem to apply: “Time and again in all the works dealing with the same subjects and sharing the same sources, one finds the same bits of information paraphrased more or less successfully, often with the same words endlessly repeated. Other people’s findings, acknowledged in underhand fashion, re-emerge as so many new discoveries, stripped of quotation marks and references, and more often than not adding nothing to what is already known on the subject. But what this does is allow the whole field of information going unchallenged to be enlarged quantitatively, and on the cheap…”12

Culture is nothing if not what the Situationists called détournement: the plagiarizing, hijacking, seducing, detouring, of past texts, images, forms, practices, into others. The trick is to realize in the process the undermining of the whole idea of the author as owner, of culture as property, that détournement always implies.13 Thus this study makes no claims to originality. Rather, in its act of inflating the whole field of information on the cheap, it seeks only to encourage others in this far from fine art of cultural inflation. The Situationist archive is there to be plundered. Unlike Becker-Ho, The Spectacle of Disintegration makes no proprietary claims, but it does set out to be a version of these materials of use to us now.14 It’s the past we need for the critique of this present.

Situationist thought is often imagined as a species of Marxism, particularly of the Hegelian variety. Sometimes it is regarded as the inheritor of the fringe romantic poetry of Arthur Rimbaud and the Comte de Lautréamont. Sometimes its project is imagined to be that of superseding the avant-garde movements of Dada and Surrealism, and presenting a spirited rival to contemporary movements as diverse as Fluxus, Oulipo or the Beats. Sometimes it is recalled as a precursor to punk rebellion, anarchist dumpster-diving or postmodern fabulousness.15 That the Situationists took on the whole world does seem to align it with the more obstreperous of all these currents. What the Situationists fought against, much more vigorously than any of these movements, was their own success. The aim was to preserve something that could escape recuperation as mere art or theory. As Debord writes, “nothing has ever interested me beyond a certain practice of life. (It is precisely this that has kept me back from being an artist, in the current sense of the word and, I hope, a theoretician of aesthetics.)”16

The Situationists could be insolent, recalcitrant, insubordinate, but at their best their project of transforming everyday life had a playful quality. Everything is at stake, but the world is still a game. This attunement to life connects the Situationists to a quite different legacy. Michèle Bernstein, Gianfranco Sanguinetti and in particular Guy Debord were fond of quoting quite different sources which point toward different ancestors: Niccolò Machiavelli, Baltasar Gracián, Carl von Clausewitz and the Cardinal de Retz were, in their different ways, writers who tried to put into words the lessons of their own actions or the actions of others upon their time. Situationist writing thus belongs to that tradition of inquiries upon everyday life that ask: how is one to live? And that posit answers that are more than a critical theory, but form the tenets of a critical practice.

Debord was particularly fond of the Mémoires of the Cardinal de Retz (1613–79). A leader of the Fronde, that last aristocratic resistance to the imposition of absolutist monarchy in France, Retz contributes a quite particular orientation to everyday life that Situationist thought and action observes in its finest hours and neglects in its lesser moments. Writing a hundred years before Rousseau, Retz was not concerned with an armchair analysis of his inner life. He was crafting a public self, styling himself as a being in action. His Mémoires are an account of his successes and failures, but an account further perfected. A key quality with which Retz imbues his life is disinterestedness. His conduct of his affairs is something like a work of art or a well-played game. The chief aesthetic quality is being worthy of the events that befall him. He is versatile rather than a specialist. Often he acts from behind the scenes, an unseen power. The prevailing style is a certain appropriateness and consistency.

There is a certain aggrandizement to Retz, as there is to the Situationists, particularly Debord. Events are presented as if he was at the center of them. But what undercuts this seeming self-importance is a sense of the ridiculous quality of power in this world. Neither Retz nor Debord suffers fools gladly. Above all, this appreciation for human comedy relieves the writing of the bitterness of defeat. As Debord writes, in a style that is a modernized Retz: “I have succeeded in universally displeasing, and in a way that was always new.”17 To take this world seriously would be comic; to see the comedy of it is perfectly serious. What the Situationists share with Retz is a comic approach to life as a game which commits one to the cause of the world. Or to quote Debord, quoting Retz: “In bad times, I did not abandon the city; in good times, I had no private interests; in desperate times, I feared nothing.”18

Like everything else, the Situationists got caught up in the spectacle. They became a mere image of themselves. Critical reception of them finds itself led by the nose into accepting a spectacular version, in which the whole project is reduced to Debord’s personality, which is in turn reduced to a certain fanaticism.19 Alain Badiou reduces Debord to psychoanalytic terms, as posing an image of the real against the symbolic and imaginary. Simon Critchley sees him as a religious rather than an ethical thinker. Jacques Rancière sees only aesthetic project.20 Such readings take certain tactics at face value. Debord is not a modern Pascal, but a modern Retz; it is not faith but the game that is at stake.

“Of all modern writers,” Debord said, quoting the eighteenth-century writer François-René Chateaubriand, “I am the only one whose life is true to his works.”21 Perhaps the most enviable thing about his life is that he managed to avoid wage labor. He did not work for the university or the media. And yet he produced several films, edited a journal, ran an international organization, and wrote a few slim books. Debord: “I have written much less than most people who write, but I have drunk much more than most people who drink.”22

The drinking did him in. Peripheral neuritis is one of the more painful conditions from which a hard drinker can suffer. As a good Stoic, Debord put his affairs in order. He collaborated on a television documentary with Brigitte Cornand. He prepared his correspondence for publication with Alice Becker-Ho. He may (or may not) have burned certain documents. Then he shot himself in the heart. In the words of Louis-Ferdinand Céline, one of Debord’s favorite writers: “When the grave lies open before us, let’s not try to be witty, but on the other hand, let’s not forget, but make it our business to record the worst of human viciousness we’ve seen without changing one word. When that’s done, we can curl up our toes and sink into the pit. That’s work enough for a lifetime.”23

Debord was not by any means the only member of the Situationist International to leave her or his mark, and if other members did not exactly dazzle their century, they may yet have their chance to inform ours. The wager of this book is that critical practice needs to take three steps backwards in order to take four steps forward. First step back: the early, so-called artistic phase of the Situationists is richer than is usually imagined, and not so easily recuperated as mere art or architecture as is often supposed. Second step back: the political thought in action of the Situationists in the sixties is not well understood, and much of what transpired in this period still speaks to us today, if it is seen more broadly than May ’68. An early book, The Beach Beneath the Street, set itself the challenge of retracing these two steps.

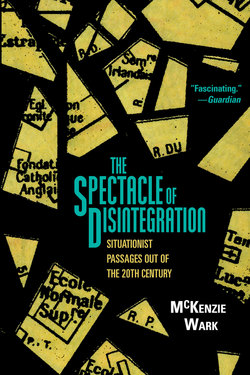

The Spectacle of Disintegration concerns itself with a third step back: that the defeat of May ’68 did not mark the end of the Situationist project, even if the organization dissolved itself shortly afterwards. This book begins again with the story in the seventies, via the work not only of Debord but also his collaborations with his last comrade in the Situationist International, Giancarlo Sanguinetti, with Debord’s second wife, Alice Becker-Ho, with his patron and film producer Gérard Lebovici, with professional filmmaker Martine Barraqué, with video documentarian Brigitte Cornand, and in the independent work of three former members of the Situationist International: T. J. Clark, Raoul Vaneigem and René Viénet. It is a disparate body of work through which we can read the last quarter of the twentieth century. They still dare us to outwit them, outmatch them. They dare us to stake something. There is more honor in failing that challenge than in refusing it.

This book is not a biography of Guy Debord. It is not a history of the Situationists. It is not literary criticism or art appreciation. Out of what is living and what is dead in the Situationist legacy it concerns itself mostly with what is living. If the Situationist slogan LIVE WITHOUT DEAD TIME is to be understood at all, it can only be in writing which treats its own archive as something other than dead time. The project is to connect Situationist theory and practice with everyday life today, rather than with contemporary art or theory. Hence the presence of certain anecdotes, cut from their journalistic context and taken on a journey, a detour, relieved of their fragmentary context and connected to a theoretical itinerary which treats them as moments of a lost totality. As the Situationists said: “One need only begin to decode the news such as it appears at any moment in the mainstream media in order to obtain an everyday x-ray of Situationist reality.”24

Debord, like Retz and so many others, failed to transform the world of his own time, but this failure is the basis of a certain kind of knowledge. Right thinking in this tradition depends on the confrontation of thought with the world. History’s winners are confirmed in their illusions; the defeated know otherwise. Debord: “But theories are made only to die in the war of time.”25 At least the Situationists found strategies for confronting their own time, to challenge it, negate it, and push it, however slightly, toward its end, toward leaving the twentieth century.

As impossible as that task was, leaving the twenty-first century may not be so easy. It is hard to know how to even imagine it. Perhaps a place to start, then, is by returning to some situations where it seemed possible to leave previous centuries. One of the virtues of writing in a Situationist vein is that it opened up the question of an activist reading of past revolutions. In our opening two chapters, we look back over the seventies writings of Clark and Vaneigem, but through their eyes look back again over the whole series of French revolutions and restorations. Then, we turn our attention to the rather critical accounts Sanguinetti and Viénet offered, from firsthand experience, of the Italian Autonomists and the Chinese Cultural Revolution, moments which, strangely, are back again, in a rather spectacular fashion, as touchstones for twenty-first-century political thought. After that, we pursue the tactics of Debord and Becker-Ho for keeping alive the spirit of contesting the totality as the era of the disintegrating spectacle was dawning.