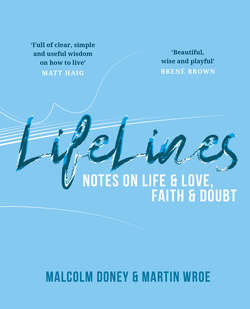

Читать книгу LifeLines - Malcolm Doney - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

What does a good life look like and where can I get one?

There’s nothing novel about this question, but the answer remains as elusive as ever. When questions about the meaning of life are answered convincingly, we’re quite likely not to notice. That’s because the ‘answer’ comes as often from the exemplary lives of shining individuals as it does from the advice of books or the words of teachers.

Still, every day we’re surrounded by questions as old as the human race, and the clues we find in one generation may not resonate so much with the next:

Why is there something rather than nothing?

What is this thing called love?

Why am I sometimes such a bastard?

Why did she have to get sick?

How come music makes me cry?

... come to think of it, what’s this life all about?

For a few thousand years, we might have looked to find answers to questions such as these in churches or synagogues, in mosques or temples. The great households of religion often claimed to have a monopoly on truth.

But then more and more of us stopped believing in them, stopped belonging to them.

Today, many of us don’t really do religion like that. We may be fine sitting in the tranquility of some ancient house of prayer, but we’ll probably slip off if anything resembling a service begins. We don’t like to be told what to believe. We’re shy of certainty, suspicious of authority.

Sometimes institutional religion itself seems to obscure the truths it lays claim to, worrying that people might interpret them in their own way, in their own lives. The gatekeepers of the faith traditions lose sleep over the terrifying prospect of their brand being diluted. It can feel like they’d rather keep people out than invite them in; that their preoccupations and anxieties are not those of the rest of us. This rigidity was summed up by the singer and activist Bono: ‘In the war between the church and God, sadly, the church is winning.’1

But if many of us feel disconnected from formal religion, still we retain a longing for some deeper, richer narrative by which to navigate our days. We’re inveterately curious, and open to ideas. We haven’t closed the door on life’s strange mysteries. How the big moments – the birth of a child, say, or the death of a friend – can leave us wondering about how to live in the small moments.

How to forgive someone.

If love is worth it.

What is enough?

Why people pray.

The authors of this book (that’s us) have grown up in quirky, generous, god-haunted backgrounds and, if we’ve shed a few convictions over the years, we’ve picked up one or two others. None is stronger than a sense that how we live is more important than what we believe. And what we talk about when we talk about faith are the kind of field notes for living a good life that we’ve scribbled down in these pages. Perhaps there’s another way of talking about this stuff, a different vocabulary.

In these lifelines we’re often holding on to the wisdom of others: artists and activists, poets and songwriters, thinkers and dreamers. Some of them can reach out and touch faith, others feel like they never grasped it. This is less of a ‘how to’ book than a ‘try this’ book. It’s more about clues and pointers than terms and conditions. It’s about how we might try to live well in this beautiful but baffling world.

Please don’t feel you need to start at the beginning and plough through to the end. It’s more of a dip-in-and-out thing. But if each spread stands alone, we hope that it’s more than the sum of its parts. Less of an instruction manual, more of a sketch book. These are not the kind of lifelines that you might throw to someone who’s fallen overboard, they’re more lines about life that might help navigate the choppy seas.

In case you’re counting, we’ve come up with 99 lines. Maybe you’re thinking that’s because, in Islam, there’s a tradition that there are 99 names of Allah. Actually, it’s probably that 99 is a number that seems reassuringly incomplete. Unfinished. There’s always room for more.

There’s another tradition, that Persian rug-makers and Amish quilt-stitchers put a deliberate mistake into their creations out of humility, because only God is capable of perfection. We may have done this too, but most of our errors are less deliberate.

We’re following Leonard Cohen’s advice to give up on the ‘perfect offering’ because ‘there’s a crack in everything.’ Hopefully, as he added, ‘That’s how the light gets in.’2