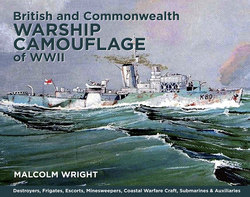

Читать книгу British and Commonwealth Warship Camouflage of WWII - Malcolm George Wright - Страница 8

ОглавлениеThis work was inspired by friends and readers of my WWII Convoy series of wargame books who felt I should publish the hundreds of colour drawings of ships that I have made over the years as well as my maritime paintings and cover art. They were gathered together over the past fifty years, sometimes from descriptions given by veterans, models in museums, works of art, etc. Where I have remembered the sources, these have been included in the bibliography. Many were taken from a study of war art that I did some decades ago. There are some which, across half a century, I have simply forgotten the origin of. In these cases where mistakes occur in the drawings I have produced, I accept full blame.

One of the first occasions on which I recall realising the importance of paint schemes used in war was when, as a boy, and later as a young man, I spent many hours in the company of various naval veterans of several nations, particularly British and Australian. Of great value was that I was able to meet two men who had served in naval dockyards: one of the two in Sydney, Australia, and the other in three dockyards in the UK from slightly before the war to just after it. It was fortunate that I met these men in the prime of their lives with memories still fresh and not distorted or dulled by age and the years in between.

These hours were many decades ago and the veterans have sadly all passed on. How I wish they were still here so I could clarify some things with them. They were kind enough to help me match colours on various model ships I built and with some of my early art work. There were colours that I found hard to imagine being used in my young days but, of course, since then there have been publications showing the paint schemes for a whole range of ships. Today we know much more about them, but even so many records were destroyed or lost. I remember one ex-sailor laughing that HMAS Hobart arrived in Fremantle from the Mediterranean painted pink. In his story, he said he thought it was because they had mixed undercoat into grey because they were short of paint, but as soon as the ship arrived in Sydney they painted it grey again. He had obviously never heard of the famous Mountbatten Pink scheme, and nor had I, so I was unsure if he was just telling a tall tale. In later years, I realised what he had seen was a well-used camouflage scheme in the Mediterranean theatre of war up till late 1942.

An analysis of colour photographs is helpful but the film used in WWII is not necessarily true to shade, with many colours appearing darker or lighter than in real life due to poor-quality film or just tricks of the light. But black and white photographs can be quite helpful if you have access to the shades that were available and which were probably used on the ship in question. With patient research, it is possible to reconstruct schemes.

In this manner, and with a lot of detective work, I have assembled line drawings of the hundreds of ships that appear in this series. If any are wrong, then, again, I accept responsibility, but would point out that in some cases there are no hard references and therefore my deductions are probably as good as any.

In some instances I was able to use the work of earlier authors for reference or to check my own research against theirs. I have not always totally agreed with some and if my drawings vary from other sources it is because that is my opinion based on the research of many decades. Sometimes the difference may be merely the size and shape of a squiggle or triangle or the exact tint of the shade.

This book is intended as a quick reference source for people wanting to paint model ships as a hobby, for wargaming or art. Mostly I show only the starboard side of a ship. This is because I found in research that a remarkable number of starboard-side views were able to be interpreted compared to far fewer portside views. It must be kept in mind that some ships did have a different layout on each side. Others did not and, of course, many standard schemes had to be identical on either side.

I have not listed them by camouflage scheme, rather by ship type. This should enable the reader to go straight to the ship type wanted and find an appropriate scheme. They are also listed by name and, while not all the ships of each class are always shown, I have nonetheless included a lot of them, so the reader can also often chose by name when painting a model. The classes include ships that were British Commonwealth-built yet manned by other navies in exile. I have occasionally included ships that were captured to show how they looked in enemy hands. There were few of them, but the changes are of great interest.

Overhead views are included with some ships as concealment from aircraft was important for much of WWII. However, where not shown, it was common to paint upper surfaces grey or in the case of Cemtex to leave it in its natural grey. Some camouflage schemes were carried across the deck. But by and large the easiest way was to use grey, even if it meant painting over wooden decks that had been kept holystoned for years by the sweat of sailors.

One of the very important issues for those painting models to remember is that sometimes there is no exact shade. There may well be a recommended shade, and even a paint guide with colour chips to go with it, but you must put yourself in the shoes of the sailors of the day. Imagine you have been at sea with a convoy for a week or two; you arrive back in harbour exhausted, in need of rest. But half the ship is sent off for a few quick days leave and the others remain behind to carry out minor maintenance. This usually meant either touching up the paintwork or preparing it for the half on leave to tackle when they returned. Laid out in front of you is a sort of cook book telling you to add this much of a certain pigment to that much white or grey and the result will be the shade specified for a particular scheme. But you are tired, or perhaps the ship is on standby to leave harbour on yet another mission. So your level of care when told to add a cup of this to a tin of that can be rather less than ideal. The famous ‘TLAR’ comes into effect. The buffer puts in the pigment, a seaman stirs it, they look at the result and say ‘That looks about right’.

Veteran after veteran told me how arduous the task of chipping rust and repainting was. It was hated. This was even more so by tired men waiting for the rest of their shipmates to get back so they could get a few days leave themselves. So up until 1943 we must accept some of the official Admiralty shades with a pinch of salt. Even they accepted that a ship may not have the right amount of paint and recommended a scheme be as near as possible. In some cases this meant the colours might not even be the same, in which instance the recommendation was that they be of similar shade tone. Hence pale blue was often used instead of pale green and vice versa. No ship was going to be held back from her vital role in war just because the paint scheme was not exact.

From 1943 onward this was eased (though never fully overcome). That was because the Admiralty started to issue ready-mixed paint to the ships along with full instructions for specific schemes. Thus in later wartime photography we are more likely to see ships looking much the same shade when wearing various regulation schemes. Also new ships coming from the shipyard would have been painted in the yard using paint delivered for the purpose.

But, to emphasise, it was never fully overcome, because there were often shortages and a ship might have to make do with what was available to the crew to use. There were instances of there being insufficient of a particular shade to cover the amount of area intended so that area was either made smaller than specified, or often the problem was solved by mixing some other spare paint to eke out the shade that was running out. Therefore you should never assume a ship is exactly one shade or another regardless of what official records might state.

The most reliable paint jobs were those provided by the various yards while ships were in for refit or repair. The crew were usually not involved and the work was carried out by workers under the supervision of a foreman painter. But even here many were not familiar with naval requirements and despite written instructions they could easily get things wrong under the pressure to get the job done and on to the next one. Firstly, they had to mark out the areas of the ship to be painted. One of the gentlemen I met who had worked in a naval dockyard said they would take measurements from drawings provided and mark the areas with a large lump of chalk. On each side of those lines they painted a dab of the shade required and moved on to another area. The painters then got to work and filled in the marked-out areas. Sometimes there was an ‘oops’ moment and a straight line now had a bend in it, or a curve was a bit flatter than originally intended. But in general it would be as marked. But of course the markings depended on the accuracy of the measurements in the first place. Hence one foreman docker might get a few things wrong that another got right. Similarly, from ship to ship supposedly painted in the same pattern these human errors were present. It is very important to remember this. The accuracy of the pattern depended on the human who marked it out in the first place. Inexperienced foreman painters could make some howlers. I have included one ship where the flag superior and pennant has been painted on along with the abbreviations intended only as notes for his reference. I have seen this in photographs on two occasions. Even shipyards ran short of paint and rather than hold a vessel up from entering service it would be sent to sea with whatever was available. This explains why the reader will see ships of exactly the same class, but which, although painted similarly, the colours may not necessarily be the same.

The gentleman I met years ago who had worked in Royal Dockyards told me that, when he started work there a few years before WWII, there were stocks of paint on hand. But they were limited to specific colours only: Primrose, buff, dark grey, light grey, white and black. Sometimes there was a quantity of Brunswick green. And always lots and lots of red lead undercoat. Therefore, when a ship required painting, or for the paint locker to be filled, they were the only ones on offer. It should therefore be no surprise that early schemes, which were worked out by the officers of the ship, would be based around what they had, or what they could mix with those shades.

During research for the ‘Insect’ class gunboats I was aware that, having been stationed in China, they would have had lots of buff and white as part of the normal stores in the paint locker. In later reading I came across a verbal account of HMS Ladybird having been given an emergency coating of ‘stone’ during the period she spent defending Tobruk harbour and needed to hide close to the shore during the day using an inlet to avoid German aircraft. There are two possibilities. One is that there were still some stores of buff on board and these were combined with white to produce stone. But then again, when on passage from China under tow, the ships of the class were stripped of armament and almost everything else. So when they were rearmed and refitted at Bombay it would have needed the original contents of the paint locker to have been put back aboard after being transported all the way from the Far East. That sounded unlikely. Then it occurred to me that I knew a gentleman who had been a stores officer with the Australian Army and was at Tobruk. In conversation with him it became obvious that they had stores of British army paint in the port and that, if the RN had asked to borrow some, there would have been little dispute about it as daily air raids were destroying so much anyway. Therefore the RN could have ‘found it’ or were given some stone on asking. As the Ladybird was considered of great value to the army, due to her gunnery support, I formed the opinion that it was more likely that the actual stone colour mentioned in writing was in fact army stone as used on vehicles and tanks. I have no proof, but it is a logical deduction. One should not pass up the chance to think these things out.

Other issues affected how a ship looked. The sudden demand for masses of paint was a major problem for all the nations involved. Even the USA, with its vast resources, ran short from time to time. This meant that sometimes the pigments accepted were below standard and faded very quickly. Those who have looked at photographs of US warships in dark navy blue will realise how quickly that faded, often in patches. US shipyards were churning out ships at a prodigious rate and, rather than delay them, new ships could be painted in what was available and the task of providing the correct shades left to the dockyard where the ship had its first refit, or for the crew to alter during the working-up period. Getting the ships completed and at sea was more important than the exact shade of paint.

In addition to poor-quality pigments fading, there were at times great difficulties in supplying particular colours. Green, for example, was in high demand by the Army and the Air Force as part of their camouflage schemes. Many shades of khaki required green pigment too, as did olive drab. For this reason, green was often not available for warships and other colours had to be substituted. Blue was in less demand by the other services and therefore pale blue often stood in for pale green in naval schemes. Indeed there were many shades of blue and blue grey used although the designer of a particular scheme may have specified green of various hues.

Lastly, not only were paint schemes affected by shortage of pigments, the ‘TLAR’ system, fading and wrong colours being available, there was also the effect of seawater on the paint itself. Ships spending lots of time at sea suffer salt corrosion and become rusty. Paint can bubble up in rust patches and flake off, exposing previous paint colours underneath. For some paint schemes this effect was very bad. White and other pale shades of the famous Western Approaches Scheme became much less effective once they became rusty. For larger ships with more crew available, touching up was much easier. But, for small vessels, keeping up with the effects of rust was very difficult. As mentioned earlier, a ship returning from some arduous mission would return to harbour with a very tired crew and touching up the paintwork was secondary to getting a good rest before heading out again. The smaller ships, with less crew, therefore had much more difficulty in keeping elaborate schemes looking smart.

So where does that leave us? I guess it is up to the person painting a model as to how specific they are. But, when using reference sources, just keep in mind that the very neat-looking ship in a photograph has probably just come from a refit or dockyard job. The ship that looks rather scruffy has probably been worked hard and had little time for the fancy touch-up jobs. I recall years ago seeing a photograph in a book with a caption that referred to a particular destroyer returning to harbour with its paint scheme in a ‘disgraceful condition’. A veteran WWII sailor looking at the book was quite derisive of the caption. It was a case, he said, of the person writing it having no consideration or understanding of what that ship must have been through in the weeks preceding the photograph for it to be in that state. No doubt he was quite correct.

So if your model-painting skills are not the best you can always claim your model ships have seen a lot of sea time. If you are a very discerning model painter that strives for total accuracy in shade, spare a thought that perhaps you may not be producing a realistic model after all, simply one that looks perfect. A more genuine approach would be to deliberately alter shades, change patterns slightly and add a rust streak or two here and there. Then you can truly claim your model is very accurate. There could be an area that has been cleaned of rust and touched up, but the new paint is not exactly the same shade. Close but darker or lighter!

A final point; when working on this book I deliberately made contact with some naval veterans and asked them their opinion of the ‘TLAR’ attitude. Most responded that it was by far the most common way of mixing paint, especially when in a hurry. Another pointed out, and then just recently yet another, that, even in peacetime, when ships were painted to regulation and with crew who had time to do it, there was nothing at all unusual in seeing a group of sister ships tied up together all resplendent in new paint straight out of the regulation tins, and all still somewhat different. In the case of flotilla craft, this could have even been deliberate to enable individual ships to be recognised while operating together.

SCALE

DRAWINGS ARE NOT TO SCALE. In order to give the reader a good view of the drawings, they have not been produced to a comparative scale, rather they are drawn to the best size for viewing in the format of this book.

PHOTOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

Black and white film varies in quality and did so even more during WWII. The armed services used vast quantities, which left civilian photographers and even military ones at the mercy of what they could obtain. As a result, true shade is not always present. A scheme can look lighter or darker than it really was. Pale blue can come out quite dark grey and give the wrong impression of the real shade. Similarly, it can fade almost to nothing and look like there is no camouflage at all.

With diligent research, one can sometimes be lucky enough to come up with multiple photographs of the same ship, from different sources. Some may be in sepia and others a variety of faded or under-exposed film. But if one knows what the colour was supposed to be, it is possible to take these, analyse them and come to a fairly reasonable conclusion as to the pattern and the depth of shade. This is helped if the collection includes the ship from different angles and one can work out the depth of shade from the sun etc. It is not perfect, but in some cases where records have been lost, it is our best way of working out what a particular ship looked like.

I have used this technique many times. It is a case of using some detective work to gather a whole range of evidence and, from that, then coming to a reasonable conclusion. It is something that requires great diligence in finding the different sources to compare, but in this day of the internet that has become much easier. With patience, one can look up the memories posted on-line either by a veteran, or his family, along with some Box Brownie photographs these people took, and compare them with more official sources.

I have touched on issues here that I have used for fifty years of my life during research. I have of course referred to official sources too. That is the easiest of all and does produce lots of ‘what it should have been’ as well as a lot of ‘what it actually was’. The archives of the Imperial War Museum in London are excellent. But I am firmly of the belief, based on personal interviews over many decades, that what was supposed to be and what actually was has not been recorded.

As the famous song goes: ‘It ain’t necessarily so.’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Dave Schueler, Andy Doty and Ian Thompson for their assistance, corrections and patient proof reading of this volume.

Mal Wright

January 2014