Читать книгу TheodoraLand - Malcolm James Thomson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Six

ОглавлениеSince I gave no advance notice of my arrivals in Weinfelden and Frau Steinemann could not be given cooking instructions, Ursel and I had the habit of dining out on the first day of my visits. The Wystübli wine bar was next to Brunnenbach Bücher on what passed in the town for a central square. I was not good company. Three books in the big bag with my skateboard lashed to it, propped up in the corner of my room, pre-occupied me.

But the plat du jour, whitefish with saffron and capers, was delicious and the local white wine helped me to relax.

“When the people who know me here in Weinfelden started dropping like flies about twenty years ago I let it be known that… while I might send flowers… I no longer attend funerals.”

Aunt Ursel was nothing if not frank.

The people who know me… not the people I know… a hair I might have split myself. But those who know me, or think they do, have a knowledge which is neither profound nor comprehensive and to a large extent constructed by me. I have kept in touch with half a dozen of the girls from university, meeting up with them from time to time. In one respect their knowledge of me is accurate; I can hold my drink. But otherwise none of us, even when pissed, give much away. Most of us had gained our bachelor degrees in Amerikanistik. Interdisciplinary American Studies are the academic examination of a culture little more than two centuries old, its society, its language, its literature. By the end of the second year I was fed up. The only American literature I enjoyed reading had been written in Paris.

In a paper I had suggested that the Americans should number their years from the signature of the Treaty of Paris which confirmed their sovereignty as an independent nation. As precedent I cited the Islamic calendar which counted from the year of the Prophet’s migration from Mecca to Medina and gives us the current Hijri year 1433. This allows commentators with a certain agenda to imply that Araby is living through its own Dark Ages. I postulated that those living between Maine and Hawaii were thus experiencing the year 229. That year, 229 AD according to a different calendar, saw the renewal of Greek philosophy through the formulation of Neoplatonism. Rash and with gusto I wrote that outposts of the mighty Roman Empire were under threat in 229 with Germanic tribes marauding southwards, even as far as Bavaria!

I was on a roll, of course. Equate Washington with imperial Rome. Throw in allusions to Tigris and Euphrates.

“Ridiculous, Thea! The Romans counted from the foundation of the city, ad urbe condita. Welcome to their year 2765… in which your paper is a miserable fail,” my tutor had admonished. As an American he had found my aspersions offensive. He was a man few of us took seriously, so Ivy League that he had a first name which sounded like a surname. Huntingdon was an invitation to abbreviation and subsequent consonantal alliteration. Only a semester of not infrequent blow-jobs changed the Hunt the Cunt’s mind about my grade. I passed the oral.

That story I didn’t tell to the other girls of our little group. In general I think we mostly lied about our sex lives. Our erotic fantasies were preferable to the our honest recollections of the mostly mundane and were far more entertaining. We did profit from our studies to the extent that we followed much of what was happening in the United States with a smugness that being in Munich permitted. Most of us were for Obama, although Franzi played devil’s advocate by appearing to agree with Fox News from time to time, both then and now.

Studying law and pre-destined for an early partnership in her father’s highly respected Munich law firm, Franzi also informed us that in the year of the American Declaration of Independence the Bavarian Illuminati, an Enlightenment-era secret society was founded. In more modern contexts the name refers to a purported organization which is alleged to mastermind events and control world affairs through governments and corporations to establish a New World Order. Franzi was, I thought, straying rashly into Dirk Seehof global conspiracy territory.

Three years after graduation Astrid was the only one married, something she thought she regretted, and had become an English teacher, which she regretted even more. She tried so hard not to look like an English teacher but failed. Her husband taught French and it was assumed that he had that Gallic approach to marital fidelity.

Franzi, who had been the cleverest of all of us, had greatly disappointed her father. She insisted she totally loved her job delivering parcels for UPS, smugly reminding us that her shit-brown van was electrically powered. Franzi didn’t laugh, she cackled, she was unpredictable and mostly fun to have around. A big girl, she was equally likely to turn up in deep-house grunge or Palm Court vintage. She had a boyfriend, Leonard, whom none of us ever met and who may or may not have been a professional musician.

Heidi did not have long blonde braids since she had been born in Ethiopia before being adopted by a couple who were devout Catholics and proud Bavarians. She had flirted with the idea of rebelling by joining an abstemious Evangelical Christian sect but we had saved her, reminding her of her predilection for Chardonnay and Chablis and other Bacchic deities. Neither her sexy style of dancing nor her casual amorous conquests would please the ‘born again’ crowd. Now she worked at a five-star hotel where her back skin and brown uniform harmonized with shiny granite and soft suede of the hotel’s dramatic lobby.

Hannelore Ibbs was known as Lore. Her much older brother, Janis, was a typographer with an irresistible sense of mischief to which I succumbed for six autumnal weeks. Janis had decided that his sister should be called Lore Ipsum. This appellation Hannelore sometimes used in her cunning manipulations of the German social benefits system. To this source of income she turned with regularity when yet another of her highly imaginative business ideas turned out to be a fanciful non-starter.

Jenni found herself so captivated by the hyper-American mystique of Route 66 that she became passionate about highway building and dropped out to study civil engineering instead. To be candid, she quite quickly became a mono-thematic bore. She developed Tea Party leanings but was clever enough to keep quiet about it. To our relief she rarely joined our group’s bar-hopping extravaganzas any more.

Astrid, Margrit, Heidi, Hannelore and I, five fellow travellers on the yellow-brick road of Amerikanistik, all of us too cowardly creatures to exit the highway when we saw that it led, if not to hell, then to a certain dead end even after passing the toll-booth manned by Hunt the Cunt.

Foolishly, the rest of us thought, Margrit had moved in with the aforementioned Hunt who, she soon discovered, was an opportunistic unfaithful bastard, but of the American rather than the French kind. I should have warned her about the man. Although, since she now worked in insurance, she should have been able to figure out the odds.

Eva was tiny, androgynous and studying pre-med. She would one day resolve her gender dystrophy, or so we all hoped. She was a good-natured girl, ingenuously impudent at times. She had been notably touchy-feely in our college years, tending to throw some of us adoring glances which we were not supposed to notice. But we presumed that she was still not even close to coming out.

All of us agreed that it was admirable that three years after gaining our degrees we kept in touch rather than drifting off when our studies ceased to be a common experience. With only one of our number distracted by matrimony it appeared that our posse could last a good few years more.

Marriage! I had a view which I kept to myself, that as the autocratic ruler of TheodoraLand (population one) I would have no husband. A consort, perhaps. One day.

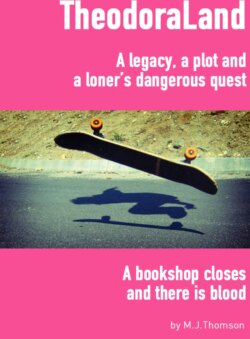

What I also told none of the others was that I stood to inherit Brunnenbach Bücher and the big house overlooking Weinfelden.

“You are not fucking listening to me,” said Ursel Lange, loud enough to alarm the very Swiss middle-aged couple at the table next to ours. As I said, blunt.

“Sorry! I was thinking abut my Munich crowd.” Our last drunken tour of the bars and clubs had been just before Herr Lessinger’s demise. I had needled some of the others (no, not Astrid) who this year wore very brief shorts, mostly in denim, although Eva’s were boyish Lederhosen. The summer before I had been the only one in extreme cut-offs. Heidi called it ‘mirroring’ and said I should take it as a compliment.

“God, they’re not all on the way here, are they?”

“No, just Dirk and Bea.”

“You did tell me a bit about Dirk, made mention of his manly magnificence,” said Aunt Ursel with a little gotcha smirk, hoping I might cringe.

In other respects he’s quite normal, I countered, omitting to point out that he tended to live much of the time in a fantasy world of cops and robbers and other ne’er-do-wells. And I elaborated upon the utter ordinariness of the ‘greige ghost’ and Bea Schell’s determination to be as good as invisible.

“Hah!” Ursel would say a few days later.

Fairouz, Ursel’s preferred Weinfelden taxi driver, responsive whenever speed-dialled, took us back up the hill. He talked as usual non-stop on his cellphone with some of his numerous children, friends, acquaintances and relatives in melodious Tamil.

I had confirmed that our joint floral tribute had been one of the largest at the funeral of Ludwig-Viktor Lessinger.

“But not… well… conspicuously big, I hope?”

Strange question.

“His two more recent lady friends… who of course met for the very first time at Nordfriedhof… had ordered smaller wreaths which were almost identical.”

I explained Vera and Agnes in soap-opera terms.

“I think both of them were miffed that none of the books he… took with him… were from their own collections.”

Aunt Ursel made no comment about the odd notion of wishing books of any kind to be put in one’s coffin.

“Three of his precious Latin incunabulae, I suppose, to read on his crossing of the Styx.”

I had not said that there were three books involved, had I?

Dirk Seehof would have spoken of ‘tells’. He rejoiced in the jargon of the clandestine worlds, the vocabularies of policemen and agents, detectives and spymasters. There were tiny tells, almost imperceptible out-of-character reactions, changes of posture, evasive glances, as Ursel listened to as much of the story as I was prepared to reveal. Bea’s speculations about interested Italians and Dirk’s involvement I kept to myself although I did admit that they were as intrigued as I was. When I finished my aunt knew as much but not more than Rudiger Reiß, whom I also had not mentioned.

“Piqued your curiosity, I suppose. Quite understandable,” said Aunt Ursel, frowning at the microwave. She had never been quite convinced that the device provided a better way of preparing her bedtime Ovomaltine.

“The books, then, have been cooked… incinerated… cremated,” she said, watching her mug spin behind the little oven’s window.

“So it would appear,” I said.

“Yes, so it must appear. Good night, Thea.”

Unusually I gave her a quick hug, careful not to cause Ovomaltine spillage. I think Ursel saw my awkward embrace as a big fat tell.

WEDNESDAY 6 JUNE 2012

I find it easy to slip into a laid-back Säntisblick mode. There were strenuous but enjoyable hikes with Aunt Ursel, meals prepared by Frau Steinemann or by me when I could persuade the housekeeper to vacate the kitchen. There were a couple of rainy days when the television in the Bauernstube showed more than football.

There was much impassioned discussion between talking heads about the morality of drone strikes in Afghanistan. Bea, I thought, would have concerned herself only with the advanced technology involved in this new way of slaughtering innocents. Pundits painted a gloomy picture of what the crash of the Japanese stock market could mean for us all. Queen Elizabeth, honoured in lavish Silver Jubilee celebrations, provided further gracious proof that Aunt Ursel’s generation could be very resilient indeed. Dirk would have commented on unresolved plots and conspiracies involving British royals.

He and Bea were on their way.

My room in the house on the hill has an en suite bathroom, which is cool, and last year I had invested in a top-of-the line Turmix espresso machine, made in Zurich by a company founded in 1933 by Traugott Oertli, a name I find kind of cute. It was well worth the price for it meant that I can have my first shot of caffeine without the need to leave my quarters. Years ago Frau Steinemann made it quite clear that she was uncomfortable with me wandering around the house in the nude, although I know it didn’t bother Aunt Ursel at all.

A sepia tinted photo in an Art Deco frame at the foot of the stairs in the entrance hall, not easily missed by any visitor, announced that the high-walled garden of Säntisblick, at least, had been a ‘clothing optional’ enclave back in the very late forties. I chose to make the same assumption, particularly when the weather was as inviting as now. Anyway, the espresso machine in my room had been a good idea. Decaffeinated manque avoided. Propriety preserved, at least indoors during the earliest hours of a new day.

However perched on my chair on the narrow balcony with my double espresso today I felt not just naked but also defenceless.

Bloody Dirk!

His follow-up piece on the blog of the Munich newspaper that few read started out innocuously enough as a reasoned discussion of ‘grave goods’, personal possessions, supplies to smooth the journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods, interred with a person deceased. King Tut’s little chair made of ebony inlaid with ivory. The American who in 1899 requested that he be dressed in a hat and warm coat with the key to the tomb inside his coat pocket. Movie star Humphrey Bogart was buried with an inscribed silver whistle. In 1944, he starred in To Have and Have Not with Lauren Bacall, who became his fourth wife. A famous line from the movie, delivered by Bacall to Bogart, was, “If you need anything, just whistle.” When California socialite Sandra Ilene West died in 1977 from a drug overdose, she was buried in San Antonio, Texas, in her 1964 Ferrari 330 America. She asked to be clad in her favourite lace nightgown with the driver’s seat positioned at a comfortable angle.

So far, so Google.

But in his closing paragraph Dirk insisted on originality. Having argued that the inclusion of grave goods was by no means a practice which had died out after Christianization Dirk Seehof went on to refer to the more recent and local example.

“The distinguished old gentleman who might well have been a further fatality when an explosion devastated Manduvel Books on Trinity Place last week was cremated with grave goods. It was his wish to depart with three precious Latin manuscripts, either from his own collection or perhaps the three items missing from the antiquarian inventory, as reported by his successor at the Bookshop.”

Elsa Brundt was never Lessinger’s successor. She had only chosen to sit in his cubicle and pretend that she was.

Lessinger collected no handwritten manuscripts, only incunabulae, precious examples of the earliest secular printing. He would never dream of letting any one of them be destroyed.

Oh, for sure it made a half-decent story. I wondered what Rudiger Reiß would make of it. At our asparagus dinner I had had the impression that the Manduvel man didn’t take Dirk seriously, almost yawning when our boy detective went off on a long rant about the merits of Scandinavian noir and its influence on contemporary crime fiction.

Dirk. Cute, yes. Big dick, smaller brain.

The colour of Bea’s old Toyota could be called a kind of grey or a kind of beige and could be seen as fitting.

But for two things.

The engine of the Corolla had been tuned and equipped with new motor management electronics (tweaked with confident skill by Bea herself) boosting its output from 90 to 120 horsepower. That I had long known, and that Bea Schell was inclined to drive like a demon.

But new that morning as Bea climbed out of the car in the short driveway of the Weinfelden house was the look of the driver. She was the ‘greige ghost’ no longer.

Somehow I expected her to shout. She spoke a bit louder than before, though.

Her drop-crotch sweatpants (smiley yellow with an aqua strip down the legs) hung low beneath angular hip-bones. The cropped teeshirt was inky black, printed in white proclaiming an affinity with the Sam Houston Institute of Technology, the four big initials boldly legible when her bottle-green and very long grungy cardigan fell open.

Chucks? Red? Whither the always-shiny Bea ballerinas?

Long ash-blonde hair? Now urchin short and a full shade lighter, with faux-Versace sunnies where there had always been her Alice band. We were on the far side of the Looking-Glass now. Bea is as tall as I am, she has the broader shoulders and I the narrower hips. I knew she had formerly resorted to cleverly engineered underpinnings to emulate a cleavage more opulent than either mine or her own when not artificially boosted. No more. Today she looked incredibly sexy, I realized.

“I know what you all used to call me. Meet Bea ‘two-point-zero’, Thea!”

Dirk’s appearance also called for explanation. When he lowered the top of his grey hoodie I saw that while his face was not quite as colourful as his fiancée’s outfit it wasn’t far off. A laceration shone red. A closed eye was almost black and extensive bruising had hues of dark green and blue. The bandage on his jaw was a pale aqua colour and yellowish tincture of iodine had been applied to places which looked as if they might hurt quite a lot.

“Ouch! Partner look… colour coordination taken a step too far. What the hell happened to you?”

He drew a deep, uncomfortable breath and concentrated on getting out of the Toyota.

Bea’s account delivered on his behalf was succinct.

They had arranged to meet for a pizza. Bea had driven from her workplace on the south side of the city. Dirk had rode on his cherished fixie bike, on which he was the scourge of pedestrians, other cyclists and motorists alike. Using their respective modes of transportation they had headed after dinner for home and bed, the latter destination stressed by Bea Schell.

Right. Still possessive, even if two-pont-zero.

“There was a collision.”

But it had been a very minor one, enough to unsaddle Dirk, but not more. Except in that it left him dazed and tottering when fallen upon by three young thugs who proceeded to give him a thorough beating. The punishment could have continued but for the arrival on the scene of two buffed gays walking their Staffordshires. They turned out to be medical students.

Maxvorstadt, the university neighbourhood next to the district where I live, is not a hotbed of crime, not a place where muggings are commonplace. Munich is proudly Germany’s safest large city. And nothing, not even Dirk’s fixed-gear velocipede (which was almost as valuable as he thought although I mocked it as beacon of pretentious hipster fad-following), had been stolen.

“There are a lot of haters of guys who ride fixies. Or… were they the infuriated brothers of some girl…”

“Very funny, Thea,” said Bea.

Dirk sighed.

“I know you think I have a runaway imagination. But… it could have been a warning… well, maybe I shouldn’t have posted that latest story.”

“It is no longer online. I saw to that,” his fiancée added.

“You can do stuff like that?”

I had always suspected that Bea could do devious digital things of which most of us were incapable. Her high-tech employer, Segirtad GmbH, was in Pullach, cheek-by-jowl with firms in the avionics sector, pioneers in green energy, as well as a well-known cutting-edge sound recording studio where I once attended a session with my earnestly anarcho-rastafarian albino musician. The building where Bea worked was bland, modern and very secure. Programs for automated stock trading, for actuarial computation, for number-crunching of big data involved a high degree of confidentiality, Bea had pointed out, adding disingenuously that she was a mere nonentity in the accounts department. Sure. The ‘greige ghost’ was (among other things, I guessed) a wicked code jockey, whatever else her new iteration might turn out to be.

The intelligence agency of the German government, the Bundesnachrichtendienst, is also headquartered in Pullach.

Bea Schell laughed.

“And now I even look like a hacker! How cool is that?”

Not so cool, I thought. She’s a year older than I am but Bea now looked like a teenager. She was edging into the spotlight I had always considered my own personal space, reserved for someone flamboyant, kick-ass, intelligent, sexy, although at the moment also apprehensive.