Читать книгу Walking Hampshire's Test Way - Malcolm Leatherdale - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

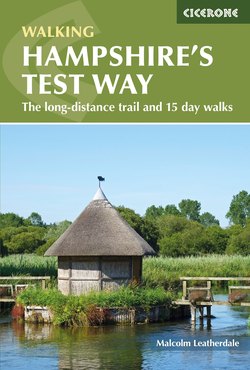

From Houghton Bridge (Walk 12)

For some, the magic of the River Test is all about fresh water fly-fishing but for others it is simply the lure of a sparkling river famously described as ‘gin clear’. The Test flows majestically the 40 miles (65km) from its source in the hamlet of Ashe near Overton in north Hampshire to the edge of Southampton Water. There is though, so much more to this land of vibrant green – its variety of landscape, gently sloping tree-clad hills, the occasional remnant of a former water meadow or chalk grassland – all set against a backdrop of a fascinating history and geology. Add to that the vast array of wildflowers, plants and wildlife inhabiting the various Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) – including Stockbridge Down, a haven for many species of butterfly – and it is not difficult to understand the attraction of a place that so completely defines pastoral England.

Chalk streams are a very rare breed among the various types of river that can be found on our planet. Such streams naturally occur in those areas where chalk is the main geological feature. Water seeps through the porous chalk to feed the springs that in turn give rise to rivers such as the Test. The pure water, rich in nutrients, also helps to maintain a plentiful supply of insects on which fish stocks rely (please refer to the section Geology and landscape). There are only about 200 chalk streams worldwide of which 160 are in England and the River Test − also an SSSI − is one of the finest examples.

Some of the area’s history is quite intriguing, notably the murderous story of the Saxon Queen Elfrida and the founding of Wherwell Abbey in the 10th century. The monument known as Deadman’s Plack in Harewood Forest is also a part of that story, albeit from the 19th century. There are an infinite variety of medieval churches with their own particular histories to share; St Mary’s Church in Broughton has the distinction of hosting one of only four ecclesiastical dovecotes that remain in England.

Nor is there any shortage of individual buildings of outstanding architectural quality as the 12th century Romsey Abbey, the resplendent Mottisfont Abbey (now owned by the National Trust) and the unique Whitchurch Silk Mill bear witness. There is also the dramatic impact of our forebears − the imposing Danebury Iron Age hill fort being one example. You can also discover the delights of the many charming villages brimming with flint and thatch and individual ‘hostelries’ to match.

Romsey Abbey (Stage 7/Walk 15)

The spate of canal construction that took place in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and the railway ‘mania’ that followed have also left their distinctive mark. At the ivy covered remains of the former Fullerton Junction station you can imagine that in the heyday of the Andover and Redbridge railway (generally known as the ‘Sprat and Winkle’) the scene then would have been very different from the sense of tranquillity that can now be enjoyed. Some of the old track bed also forms part of the Test Way (TW).

The TW begins in the North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in West Berkshire and then runs in parallel with the Wiltshire county boundary for a short distance before crossing into Hampshire at Combe Wood. It then continues through rolling chalk downland traversing Harewood Forest either side of Longparish – which is also where the TW first meets the River Test. From the hamlet of Fullerton at the half-way point, the route joins the old track bed of the former 'Sprat and Winkle' railway, becoming flat and fairly straight as it makes its way to Mottisfont. The penultimate stage to Romsey includes Squabb Wood and the final stage to Eling Wharf at Totton crosses the unique tidal estuary Lower Test Nature Reserve.

Last but not least, there are the 15 circular walks, which vary in length from 3.75 miles (6km) to 8.5 miles (13.75km). A few have uphill challenges (usually with rewarding views) but none are overly difficult, so when taken together with the individual stages of the TW, there is something for everyone. Ten of the walks also interweave with parts of the TW so it is possible in the course of those walks for you to achieve the best of both worlds!

Wherwell thatch (Walk 5)

Brief history of the Test Valley

Dating from the Neolithic period (4500–2200BC) there is evidence of farming activity in large parts of the Test Valley. There are relics from the Bronze Age (2200–750BC) including barrows or burial mounds, 14 of which are to be found at Stockbridge Down (Walk 10). During the Iron Age (750BC–AD43), a number of hill forts were constructed in and around the Test Valley including Danebury (Walk 8) and Woolbury Ring at the top of Stockbridge Down.

The Romans who invaded in AD43 and remained until the beginning of the fifth century have also left their imprint. There is a trace of a Roman road across Bransbury Common (Walk 4) and in Harewood Forest (Stage 4). The Anglo-Saxon period (AD450–1065) saw the development of a number of settlements, particularly Romsey (Stage 7 and Walk 15) as a prominent trading centre due to its location and ecclesiastical influence.

In medieval times the chalk downland areas were used intensively for rearing sheep – one of the most economically important activities during that period. The power inherent in the River Test spawned numerous water mills particularly around Whitchurch (Walk 2) where they were used in the production of cloth and at Laverstoke, especially in the making of paper for bank notes.

The Andover and Redbridge canal and the ‘Sprat and Winkle’ railway

The canal

A survey to plan the prospective route of a canal from Andover to Redbridge (on the western side of Southampton) was conducted by Robert Whitworth in 1788/9. The enabling Act of Parliament authorising construction was granted in 1789. The canal, which was 22 miles (35km) long and incorporated 24 locks, was completed in 1794.

However, the canal was never a financial success and proved to be a poor investment. There is now just a single vestige of the canal (Walk 15) – an overgrown and derelict section of about 2 miles (3km) between Greatbridge and Romsey.

The ‘Sprat and Winkle’ railway

Restored signal box from the former ‘Sprat and Winkle’ railway in Romsey (Walk 15)

In 1858, an Act of Parliament authorising the construction of a railway to replace the canal was granted. Before work could start, the railway promoters had to acquire the Andover to Redbridge canal itself as it was along the canal bed that much of the railway would be laid. The purchase was completed in 1859 by the Andover and Redbridge Railway Company. The initial attempts to build the railway were however blighted by the failings and manipulative behaviour of the contractor and the railway’s own engineer, both of whom were eventually removed in 1861. Even when work recommenced, it was hesitant and sporadic. One particular stumbling block was the need to remove the congealed mud from the bed of the canal and then to fill it with chalk obtained locally to create a sound base on which the track bed could be laid – a monumental task.

In 1863, the Andover and Redbridge Railway Company was in financial difficulty and it was acquired by the London and South Western Railway. Construction of the line took until 1864 to complete but permission was not given to start operating immediately because the government inspector who undertook the commissioning survey made it a condition that the rails had to be replaced with ones more substantial. The railway finally opened in 1865 after the remedial work had been carried out.

One of the practical problems experienced during the first 20 or so years of operation was derailment. This inconvenient and no doubt expensive distraction was mainly due to the line having several sharp bends – in part as a result of the track being laid directly over the former canal bed. This unsatisfactory situation needed to be resolved and the catalyst for bringing that about was the opening in 1882 of the line between Andover and Swindon via Marlborough, which created a direct route to Southampton.

The fortunes of the Andover and Redbridge railway improved significantly due to the increase in its traffic and, as a consequence, it was decided that the line should be straightened and converted from a single to a double track. This work was completed in 1885.

The railway at some point became known as the’ Sprat and Winkle’ and there are several theories why it was blessed with such a name. One possible reason is the suggestion that the line went through areas where sprats and winkles might be harvested nearer the sea at Southampton; another refers to the single engine and carriage formation that operated over part of the line − the engine being the ‘sprat’ and the carriage the ‘winkle’!

The railway was strategically very significant in World War 1, providing transport for both personnel and munitions. During World War 2 it was also used extensively and particularly in the latter stages to transfer wounded service personnel from Chilbolton airfield (Walk 7) via Fullerton Junction (Walk 6) to the American hospital at Stockbridge.

From the 1950s the use of the railway for both freight and passenger traffic gradually declined. The line between Andover and Kimbridge (Stage 7 and Walk 13) had become financially unviable and was closed in 1964 as one of a series of closures of parts of the rail network made in the wake of Dr Richard Beeching’s report, The Reshaping of British Railways, published in 1963.

The ‘Longparish Loop’ also known as the ‘Nile Valley Railway’

There is another strand to the ‘Sprat and Winkle’ story. In 1882, an Act of Parliament was passed authorising the construction of a branch line of about 7 miles (11km) from Fullerton to Hurstbourne where it connected with the London and Salisbury mainline at the viaduct just south of St Mary Bourne (Stages 2 and 3). This branch line, which was completed in 1885, became generally known as the ‘Longparish Loop’ (the Loop), and Fullerton became Fullerton Junction.

The quiet remnants of Fullerton Junction (Stage 5/Walk 6)

It was an expensive project as it turned out. The hope and expectation was that the existence of this connecting line would encourage more traffic from Manchester and the midlands to Southampton rather than let a rival railway company construct a more direct line to Southampton through Didcot, Newbury, Whitchurch and Winchester. It was put to the promoters of the alternative line that they should ‘join forces’ to save the expense that would be incurred and instead make use of the Loop.

In the event the proposal was rejected and the more direct line was constructed which meant the Loop never fully realised its potential. It was mainly used to transport freight as the passenger business was limited due to the lack of demand. Together with the ‘Sprat and Winkle’ railway, it was particularly useful during World War 1.

Passenger traffic ceased in 1931 and the track between Longparish and Hurstbourne was removed in 1934. The remaining part of the track between Fullerton Junction and Longparish came in to its own again during World War 2 when Harewood Forest (Stages 3 and 4 and Walks 3 and 5) was used for the storage of munitions by the RAF. It was closed for good in 1956 and the track removed in 1960.

Geology and landscape

The ‘ribbon’ of chalk and flint at Inkpen Beacon (Stage 1)

The TW begins at the escarpment of Inkpen Beacon at a height of 280m. It is astonishing to think that at one time this area was at the bottom of the sea. The geology of the North Wessex Downs, is mainly upper chalk formed during the Upper Cretaceous period (99–65 million years ago). Upper chalk is soft white limestone and is the product of the fossilised skeletal remains of countless microscopic marine algae and other creatures.

The chalk deposits also contain flint nodules in large quantity. There are some parts of the downland that are covered by shallow deposits of clay; these also contain flints but to a lesser extent and are known as clay with flints. The availability of flint has led to its wide use as building material throughout the Test Valley.

Chalk is also porous and permeable and therefore the soil drains easily. As the chalk is gradually dissolved by the rain it becomes alkaline and ‘hard’ due to the calcium content. The underlying chalk also acts as an aquifer or reservoir and naturally regulates the rate at which water percolates into the springs further down where the soil is not so porous and the water has to find its way back to the surface.

The springs in turn supply the river and its tributaries with water that is oxygenated, clear and full of nutrients. Significantly, the temperature of the water remains fairly constant at about 10°C. This combination of factors together with the lack of flooding (because rain water quickly disperses and does not accumulate) has also helped create the large deposits of peat found along parts of the valley floor.

The volume of water held in the chalk aquifer does vary from time to time, which means that during drier periods there may be insufficient water to feed into some of the tributaries known as ‘winterbournes’. One example is the River Swift between Upton and Hurstbourne Tarrant (Stage 1 and Walk 1).

The overriding influence of the chalk geology starts to reduce from about Houghton (Walks 11 and 12) onwards. There is a much greater prevalence of clay and gravel deposits in the lower part of the Test Valley where there are several quarries. As the Test progresses southwards it also broadens out into a more braided system or network of streams and channels that finally coalesce to form a single channel at the entrance to Southampton Water.

Water meadows

In the 18th century, water meadows were created along many stretches of the Test. This novel concept at the time was designed to extend the growing season to produce two crops of grass rather than just the one. A principal requirement was a supply of clear water at a constant temperature above freezing, and chalk streams were ideal candidates for the purpose. The intention was not to flood the ground but simply to keep it damp and at a temperature sufficient to minimise the effect of frosts during the winter and early spring. As a consequence, grass began to grow some weeks earlier than it would have done otherwise and therefore grew for longer; it was also of a higher quality as the ground absorbed the nutrients from the river.

The use of water meadows literally ebbed and flowed as the various periods of agricultural depression took their toll during the 19th century. More effective and cheaper sources of fertiliser also became available as farming methods improved with the consequence that water meadows gradually declined.

Plants and wildlife

The Test Valley is sprinkled with large areas of woodland including alder, ash, beech, birch, hazel, holly, hornbeam, lime, oak, pine, poplar, willow and yew. The woodland, together with the fertile and extensive tracts of rolling farmland and the River Test itself, provide a diverse landscape rich in wildflowers, plants and wildlife. Harewood Forest (Stages 3 and 4 and Walks 3 and 5) plays its part as a nationally important habitat populated by a wide variety of invertebrate species.

At Chilbolton Common (Stage 5 and Walk 7), 265 species of plant have been recorded including the southern marsh orchid and the snake’s head fritillary. At Stockbridge Down (Walk 10) at various times of the year, violets, wild thyme, horseshoe vetch, juniper and more than 30 species of butterfly including the chalk hill blue can be found. The River Test is of course renowned for its salmon, roach, bream, grayling, perch, brown trout and eel, all supported by a wealth of insects that are key to the retention of healthy fish stocks.

Clockwise from top left: Snake’s head fritillary on Chilbolton Common; Chalk hill blue on Stockbridge Down; Violets on Stockbridge Down

The biodiversity and the wide array of wildflowers and wildlife that prosper in the Test Valley do so largely because of the particular character and conditions that are created by the chalk stream environment. The valley floor, for example, is overlaid with calcareous alluvium − sand, silt, gravel and clay. Calcareous grassland harbours significant amounts of fairly rare vegetation, particularly grasses and herbs that flourish on well drained and shallow soils that also happen to contain lime. Bransbury Common (Walk 3) is one example and supports an extensive range of grasses and sedge. The tidal estuary Lower Test Nature Reserve is fed by an unusual mix of fresh and salt water, which helps to create a wide variety of habitat, particularly for birdlife including the elusive kingfisher.

Where to stay

In Inkpen village there are a couple of pubs with rooms. This is the type of accommodation (apart from hotels in both Stockbridge and Romsey) generally available at approximately 8, 11, 20, 24 and 35 miles, which coincides with the end of Stages 1, 2, 4, 5 and 7, respectively. There is no accommodation at the end of Stage 3 so it may be advisable to complete Stage 4 to Wherwell and possibly even Stage 5 to Stockbridge. On finishing Stage 6 there is some accommodation at Dunbridge 0.6 miles (1km) away or you may prefer to continue to the end of Stage 7 in Romsey where there is a wider choice.

Totton, at the conclusion of the TW does not have a lot of accommodation but nearby Southampton or the New Forest do. For more detailed information, please refer to Appendix B for a list (not exhaustive) of the different types of accommodation that are available near the route. More specific information will be found in Appendix C, which also includes websites and phone numbers. Other useful sources of tourist information are contained in Appendix D.

The White Hart at Stockbridge (Stage 5/Walk 9)

Getting to and around the Test Way and to the walks

For those who wish to be completely independent or who do not want to leave a car near the start (which is not that practicable anyway), there are mainline railway stations at Newbury, Kintbury and Hungerford with bus services to Inkpen village which is just 1.25 miles (2km) from Inkpen Beacon. Other parts of the TW that can be accessed by train and limited bus services are Stages 2, 5 and 6. Stages 3 and 4 are serviced by train and very limited bus services. Stage 7 is readily accessible from Mottisfont & Dunbridge railway station – about 0.6 miles (1km) away and the route of Walk 14 also passes within 100 metres of the station. Stage 8 from Romsey has very good transport links.

Walking the Test Way

The eight stages of the TW vary between 3 miles (5km) and 8.5 miles (13.75km). They are not just day stages and can be combined to suit your walking ability. Please refer to the Route summary tables (Appendix A) for an overall picture. It would also be helpful to check the Itinerary planner (Appendix B) for details of transport links and accommodation.

To complete the TW in two days, the first day would conclude either at the end of Stage 4 (Wherwell) after 20.25 miles (33km) where there is some accommodation or Stage 5 (Stockbridge) after 24.5 miles (39.75km), where there is a much wider choice of accommodation.

Three days is perhaps the better option, in which case you might consider the following split:

Day one – walk to the end of Stage 2, St Mary Bourne (11 miles (18km)).

Day two – walk to the end of Stage 5, Stockbridge (13.5 miles (21.75km)).

Day three – carry on to Eling Wharf Totton (19.5 miles (31.25km)).

There is accommodation at both St Mary Bourne and Stockbridge.

If you feel the final section is too long, an alternative would be to walk the 11 miles (17.5km) from Stockbridge to Romsey (where you’ll find accommodation) on day three; then walk the remaining 8.5 miles (13.75km) to Eling Wharf Totton on the fourth day.

If you would prefer to complete the TW in segments, simply divide it into one or more stages but remember to take into account any transport limitations.

Between Michelmersh and Lower Brook (Walk 13)

Coping with the weather and the seasons

For a lot of time, the paths and bridleways are reasonably dry, well defined and can be negotiated easily enough but there will be occasions when some parts of a route will be more difficult, especially where the chalk surface or looser surfaces have become quite slippery or unstable. The further south, the less well drained the soil becomes and hence the muddier it will be at times. This is particularly true of Squabb Wood (Stage 7). Be prepared for fluctuations in the water levels when crossing the Lower Test Nature Reserve (Stage 8). It almost goes without saying that you should always plan for the weather!

Cycling – the National Cycle Network and parts of the Test Way

Two National Cycle Routes (NCRs) coincide with several stages and walks. Route 24 starts at Eastleigh (just north of Southampton) and finishes at Bath, only just touching Mottisfont where Stages 6 and 7 and Walks 13 and 14 also intersect. Route 246, which starts at Timsbury (north of Romsey) and finishes at Kintbury in West Berkshire, is much more a feature and first joins the old track bed of the former ‘Sprat and Winkle’ railway at Stonymarsh (Walk 13).

It then follows the old track bed for 0.6 miles (1km) to Lower Brook from where it continues straight on to Horsebridge (Stage 6). There, it joins Walk 12 for 0.7 miles (1.1km) to the crossover with the Clarendon Way and Walk 9 en route from Stockbridge. At Stockbridge (Stage 5), it continues along the old track bed for another 3 miles (5km) to Fullerton where it joins Walk 6 for a short distance before diverting along the road to Goodworth Clatford and then through Andover. The last encounter with the TW is where it crosses Stage 2 just north of St Mary Bourne on its way to Kintbury.

Maps

There are two series of OS maps: the 1:50,000 (2cm to 1km) Landranger series; and the more detailed 1:25,000 (4cm to 1km) Explorer series. The OS maps covering the TW and the 15 day walks are:

Landranger: 174,185 and 196

Explorer: OL22, 131, 132, 144 and 158

Waymarking, access and rights of way

Test Way waymark disc

The TW and the walks are reasonably well waymarked on fences, gate posts, fingerposts and marker posts although, bearing in mind the combined distance of the 8 stages and 15 walks is about 130 miles (210km), it is not surprising that there is some variation in the quality of waymarking here and there. The directions in this guide, together with the map extracts and the general waymarking and signage along the routes, should however make their navigation fairly straightforward.

Each stage or walk is shown on the respective map extract − please also refer to ‘Using this Guide’. The routes all follow the official rights of way although occasionally there are permissive stretches including the unusually described ‘public concessionary footpath’ − Stage 3. Stage 7 includes a working quarry, Walk 4 encounters a military firing range, and Walk 14 crosses the railway mainline.

The main rights of way and their markings are:

Footpaths Yellow arrow − walkers only

Bridleways Blue arrow − walkers, cyclists and horse riders

Restricted byways Purple arrow − walkers, cyclists, horse riders and carriage drivers

Byways Red arrow − as for restricted byways but also motorcycles and motorised vehicles (in effect, byways are open to all traffic and known as BOATS)

Protecting the countryside

When you’re out walking, please remember the main elements of the Countryside Code:

Leave gates and any property as you find them

Protect plants and animals

Take your litter home

Keep dogs under close control

Protect wildlife, plants and trees

Take special care on country roads

All the stages and walks pass through open countryside where there may be cattle. Please always check the latest advice, especially in light of the increasing number of reported cases of injury (more numerous than perhaps might be thought) that have been experienced by walkers with and without dogs. One source of advice is the Hampshire & IOW Wildlife Trust, which publishes a brief guide called Walking with Cattle (please refer to the Hampshire & IOW Wildlife Trust website listed in Appendix D for more information).

Using this guide

At the beginning of each stage is an information box providing the start and finish locations plus the respective grid references; the distance (miles/km); the minimum time to complete the stage; the Explorer map(s); and accommodation details (please also refer to Appendix C).

Please also look at the information box at the top of each stage or walk to check the refreshment outlets. As will be appreciated, there is no guarantee that all or any will be open as you happen to be passing.

Also included is basic public transport information. Some of the accommodation, refreshment outlets or public transport mentioned may be a short distance from the actual route of a stage, in which case please refer to the Itinerary planner (Appendix B). Similar information (other than accommodation) also appears in the information boxes for each of the 15 day walks.

A standard feature for each stage and walk is the inclusion of a short overview outlining the general terrain and any particular places of interest. For every route there is a map extract from the 1:50,000 OS Landranger series highlighting features referred to in the text in bold to assist in following the route. The overlays also show the route without detours or shortcuts. To be on the safe side though, it is always advisable to take the relevant OS Explorer map.

All the total distances shown for each stage and walk are in both metric and imperial rounded to the nearest ¼ mile and have been taken from OS Explorer maps. Any height quoted is in metres. The time for each stage or walk − to be regarded as the minimum − is based on 2.5 miles/hr (4km/hr).

GPX tracks

GPX tracks for the routes in this guidebook are available to download free at www.cicerone.co.uk/953/GPX. A GPS device is an excellent aid to navigation, but you should also carry a map and compass and know how to use them. GPX files are provided in good faith, but neither the author nor the publisher accept responsibility for their accuracy.