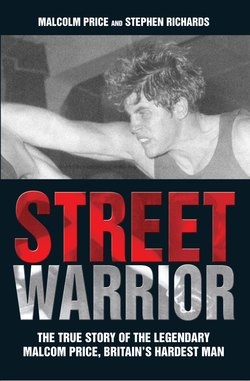

Читать книгу Street Warrior - The True Story of The Lengendary Malcolm Price, Britain's Hardest Man - Malcolm Price - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеThe role of anti-hero has often been attributed to Malcolm Price, begging the question, what is it that makes anti-heroes and underdogs such crowd pleasers?

Every so often, along comes a man who makes his mark on mankind. From the days when David won the battle against Goliath right up to the time when man first set foot on the moon, there have been heroes for us to hold aloft. Often, there are untold stories of such men and upon first hearing these tales of such godlike figures we stand in awe and, often, disbelief at their superhuman feats. Eventually, an acceptance of what they achieved sets in and the myth is accepted as legend. How such mythical stories came about is not usually questioned.

The heroic deeds of the dead can be awe-inspiring, and include such acts as those of the soldiers on the front-line trenches during the First and Second World Wars. How men risked their lives in order to save their mortally wounded mates from No Man’s Land astounds us, yet we, who have never risked ourselves in such an heroic way, can take on the role of the hero by just reading or hearing about their feats.

But what about anti-heroes? Can they be just as enthralling to us as those who have completed a superhuman deed that benefits mankind? Do we want to take on that role and adopt the persona of a hated person? The norm is for us is to be inspired by the likes of Scott of the Antarctic, the feats of Hercules or stories of how Grace Darling risked her life so that others could be saved from certain death.

The scenario where the sprawling anti-hero gets his comeuppance and the champion walks off into the sunset with his arm around the prize, usually a woman, is a pleasing one. This media personification of what a hero is all about used to be common. Examining past events can confirm this convoluted outlook that sees the baddie being portrayed as some sort of evil manifestation sent to cause havoc by any means possible.

History stands in judgement against those select few that are perceived as being do-badders. The well-known story of how the Russian ‘Mad Monk’, Rasputin, was up to no good soon changed when some filmmakers portrayed him as the one on the receiving end of others’ evil actions.

Stalin, the Russian dictator, was, reputedly, responsible for the deaths of twenty million Russians, yet he is still held aloft by his fellow countrymen as the creator of something good. People, to this day, still put roses on Stalin’s tomb.

The Welsh-made film Twin Town never received critical acclaim, but such lack of accolades gives it the cult status of never having quite made it due to always being in the shadows of the Scottish film Trainspotting. Two films that portrayed the anti-heroes as heroes! Sadly, Twin Town did not put Wales on the filmmaker’s map.

The anti-hero has played an important role in the history of mankind, so much so that the whole ethos of what is good and bad has become blurred. Examining the background of anyone can bring skeletons to our attention; a blot on the landscape can mar all that pleases the eye. This is how Malcolm Price was perceived by those who would stand back in fear of what he was all about, yet there was much more to him than that.

To really know what Malcolm Price is all about we have to go back in time so as to be able to grasp the inherent values and behaviour instilled in him by virtue of his ancestral history. To be perceived as the hero, then the anti-hero and then the born-again hero needs some explaining.

Malcolm Price embodies all that is Welsh, aside from the green valleys and male voice choirs. The will to win against insurmountable odds is a penchant of the Welsh. Put this together with a propensity to never say ‘die’ and you begin to see what makes the Welsh so durable.

In the early 400s, Cunedda of the Gododdin settled in northwest Wales to defend the country against Irish attacks. Saxons were given permission to settle, as long as they helped fight off invasions by the Picts.

An army of Saxon ‘hard men’ was to see off attempts at a takeover, but by the late 400s the Saxons were starting to get a little too big for their boots and wanted to establish their own kingdoms within Britain. Along came a man by the name of King Arthur (Artorius Rex), and the Brythonic hero thwarted these Saxon attempts, if only for a short while!

In the 400s, Viroconium (Wroxeter, in Shropshire) was the capital of Powys. An inscribed stone dated to circa 480 was discovered in 1967, commemorating King Cunorix. Quite possibly, Arthur may have succeeded Cunorix, but Geoffrey of Monmouth says Arthur died in 537 at the Battle of Camlann.

The treacherous nephew of King Arthur, the evil Mordred (also called Maglocunus), was fabled to have killed Arthur in the battle at Camlann, so says Geoffrey of Monmouth. According to the Annales Cambriae records, it is said that both Arthur and Mordred fell at the battle.

The city of Viroconium was not abandoned until AD 520. There was no threat from the Anglo-Saxons for around 20 years, and Powys did not fall to the Anglo-Saxons until the 650s.

The Iron Town of Merthyr, in Wales, is the birthplace of Malcolm Price. Seeking to join present with past inspires a theory on the origins of King Arthur. This theory suggests that Arthur was king of Glamorgan and Gwent (Arthur ap Meurig ap Tewdrig). This person, it is said, was an early Christian centred on Caerleon and a string of hill forts. He died about AD 575, possibly at Merthyr Tydfil. His body was taken to the coast by ship to Ogmore up the River Ewenny and buried in a cave by the saint who, it was said, was Arthur’s cousin. His body, legend has it, was left in a cave for some years so as to keep his death a secret until his son Morgan came of age.

By AD 650, most of England was under Saxon control, but that’s as far as it went! The Saxon hopes for expansion were rendered impotent when it came to reaching out for glory beyond the Welsh mountains.

The territory of Wales was defined by a dyke, which stretched from sea to sea. In AD 780, the king of Mercia, Offa, ordered the construction of Offa’s Dyke.

The territories of Wales were dispersed to the west of the dyke. Of these, Gwynedd (northwest Wales) was the most expansionist. The need to defend Wales from Viking attacks meant that some unity was needed.

Rhodri of Gwynedd (died AD 877) brought these kingdoms together and under his control, although it was his grandson Hywel (died AD 950) who finalised the unification process. In 1063, Harold, earl of Wessex, invaded Wales and Gruffudd was hunted down and killed.

The thirteenth century saw what was the most ambitious attempt to create a Welsh state. The rulers of Gwynedd paid homage to the king of England on behalf of the native rulers, and the lesser Welsh rulers paid homage to them. This policy was pursued by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (died 1240), his son Dafydd ap Llywelyn (died 1246) and his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (died 1282). Their task was eased by the fact that the other major Welsh polities, Powys and Deheubarth, were, in the early thirteenth century, being divided into ever-smaller entities.

The principality of Wales, ruled by a Welsh dynasty, lasted from 1267 to 1282. Its first ten years were a period of hope, indicating that there were in medieval Wales all the elements necessary for the growth from factions to statehood.

Relations with the English crown deteriorated and, in 1276, the new king, Edward I, declared Llywelyn a rebel. Because of this, the prince was forced to submit. Through the Treaty of Aberconwy of 1277, he ceased to be overlord of most of the lesser Welsh rulers.

In the following five years, Llywelyn sought to consolidate his diminished principality, but, in 1282, his brother, Dafydd, rose in revolt, a revolt which Llywelyn eventually joined. This time, Edward was determined to achieve total victory. Llywelyn was killed near Builth on 11 December 1282 and Dafydd was executed at Shrewsbury in 1283.

Following Llywelyn’s defeat, his principality was organised into six counties that were granted to the king’s heir; thus the principality of Wales survived as an adjunct of the crown of England.

From the goings on just mentioned, it would be no surprise for you to learn that the people of Wales are descended from many ethnic groups, including the original Britons and other population groups including the Celts, Romans and Scandinavians. Around three-quarters of the present population of 2.94 million are concentrated around the large cities and mining valleys of the south-east of the country. In the last 100 years, Wales has welcomed many diverse new groups to settle and be part of its population, which is in direct contrast to the fierce defence of their borders that characterised Welsh history.

Had the fight been kicked out of the Welsh or was this about-turn connected to some ulterior motive? The two centuries after the conquest of Wales were a period of contradictory developments. Although there were no longer princely patrons, the poets flourished, with Dafydd ap Gwilym (died circa 1370) pre-eminent among them. Towns and trade developed, but the Black Death of 1349 cruelly reduced the population. Although most Welsh customs were unaffected by the conquest, the Welsh system of landholding was gradually undermined, and the estates of the gentry began to emerge.

Many Welshmen came to accept the conquest and large numbers of them served in the armies of the English kings. At the same time, there was resentment of English rule, which found expression in revolts in 1287, 1294 and 1316, and in serious disturbances in the 1340s and the 1370s. Above all, there was the great revolt of Owain Glyndwr (1400 – 10), which almost led to the re-establishment of Welsh rule.

A century after the Black Death, there were signs that the Welsh economy was recovering and economic growth occurred in the context of a ramshackle administrative system. The division between the principality and the March continued, and Welsh marcher lords were active on both sides in the Wars of the Roses (1455 – 85).

During the wars, the Welsh sought a deliverer among the various leaders of the Yorkists and the Lancastrians. The most convincing was Henry Tudor, of an old Anglesey family, the descendant (through his mother’s side) of the House of Lancaster. Landing in Wales in 1485, he received considerable support, and Welshmen constituted about a third of his army.

The Welsh fighting spirit had been utilised in the Battle of Bosworth and this won the English crown for Henry VII. By the reign of Henry’s son, Henry VIII, most of the marcher lordships had come into the hands of the king, the context of the passage in 1536 of the so-called Act of Union.

The fighting was done; the heroes and anti-heroes are recorded in the annals of history. At various times in life we all take a chance; crossing the road without looking properly or simply standing on a wobbly ladder! You might get knocked over by a passing car or fall off the ladder, but there are no medals if you get hurt!

Transfer this scenario to the realms of sporting heroes and we can see that we could all be up for a winner’s medal! To be able to consciously take chances in order to win is the ingredient that sets champions apart from us all. Many of the key figures in history previously mentioned took a chance or two – just think of the treacherous Mordred!

To call Malcolm Price (Pricey) a ‘chancer’ would be wrong. Pricey has, with premeditated determination, won his battles and hung up his gloves; his story is no less dramatic or tantalising than that of his Welsh ancestors. The energy Pricey channelled into fighting has now been channelled into good. This re-channelling of energy for the betterment of all can be seen to run through Pricey’s veins, and was obviously gained from his forebears.

Having covered some of the darker side of Welsh history, it makes it all seem gloom and doom, but what about some of the heroes of the Industrial Revolution? The blood of King Arthur might run through the veins of every Welshman, but equally so does the blood of achievers of greatness.

The Valley of Rhondda might have been plentiful in coal, but ‘Merthyr’ was the capital of the valleys and supplied something that was to propel the name Merthyr into the new Industrial Age.

In 1750, Merthyr Tydfil was a quiet village surrounded by lush green fields. Most of the 40 or so families who lived in the village worked on the land. However, this situation was to change when it became known that coke could be used for smelting iron. Merthyr Tydfil, with its large supplies of both iron ore and coal, was an attractive site for the ironmasters. Ironmasters from Sussex came into the Welsh valleys and exploited the resources.

As early as 1583, a small works at Pontygwaith was set up and the Dowlais Iron Works was born and went on to become the largest in the world. The local communities supplied men of iron to work the valleys. At first, the ironmasters imported experienced workers from other iron-working areas such as Shropshire. In an effort to persuade these skilled men to move to Merthyr Tydfil, they were offered relatively high wages and good housing.

The ironmasters also needed a supply of unskilled labour from other parts of Wales; they had to build houses for these people. Whereas skilled workers with families were usually provided with four-room terraced houses, unskilled workers were only given one- or two-roomed houses.

Eventually, large numbers of immigrants came into the area from places such as Russia, Ireland and Spain.

Over the course of a hundred years, various names became synonymous with these Iron Works: Thomas Lewis purchased the first lease in 1757 and set up a rather primitive furnace next to Dowlais Brook. Anthony Bacon set up the first furnace at Cyfartha. John Guest successfully managed Dowlais and started supplying some of the cannon used by the British forces in the American War of Independence (1775–1783).

Richard Crawshay leased the Cyfartha Works in 1786, and became sole owner in 1794. When, in 1802, Lord Nelson, the Commander of the British Fleet, paid a surprise visit to the Cyfartha Works in Merthyr Tydfil, Crawshay shed tears of joy and shouted to his workers, ‘Here’s Nelson, boys; shout, you beggars!’

By 1801, Ynysfach had two blast furnaces built by Thomas Jones of Merthyr Tydfil. These furnaces were large for the period – 53ft in height and had steam-powered blast, which gave a much higher output. Local ore was prepared there. By this time, over 8,000 people were living in Merthyr Tydfil, making it the largest town in Wales.

It is claimed that the first journey by steam locomotive running on rails took place in Merthyr Tydfil in 1804. This journey was made by Richard Trevithick, and was partly brought about as the result of a wager!

By 1830 richer ores were imported to Ynysfach via the Glamorganshire Canal. After the strike of 1874 the Cyfartha Works were converted to steel production.

In April 1831, riots broke out in Merthyr Tydfil when the House of Lords defeated the proposed parliamentary Reform Bill. The leader of the reform movement in the town was imprisoned but a crowd of 3,000 people surrounded the prison and forced the authorities to release Thomas Llewellyn.

By June, another rebellion followed in which 26 people were arrested and put on trial – two of the men were sentenced to death and several others were transported to Australia. Already, Merthyr was building a reputation as a town not to be messed with and the men were as hard as iron.

By the 1830s, the Dowlais Works was owned by Josiah Guest. The owner of another ironworks near Merthyr Tydfil, Anthony Hill, joined forces with Guest and they formed the Taff Vale Railway Company. A very talented engineer from Bristol, Isambard Brunel, was assigned the job of building the railway.

The Taff Vale Railway was born in 1841. Now it was possible to transport goods from Merthyr Tydfil to Cardiff in less than an hour – Wales was becoming smaller, or so it seemed. Further branches were built, which linked the mining valleys with Welsh ports and England’s fast-growing industrial towns and cities. Welsh coal, hewn from the valleys, was profitable enough to be transported to countries as far away as Argentina and India.

As always, there is an anti-hero, and in this case it was the ironmasters who diverted the water from the River Taff in order to supply their steam engines. As a result the Taff became an open sewer. Outbreaks of typhoid and cholera were common, Merthyr had a poor freshwater supply and by 1848, Merthyr Tydfil’s mortality rate was the highest in Wales and the third highest in Britain! Most of the deaths were suffered by children under the age of five. And so the heroes had changed into anti-heroes.

Merthyr Tydfil was the most significant Welsh town of the Industrial Revolution. The industrial landscape (late-eighteenth to nineteenth centuries) is still evident. Merthyr was one of the areas to put up the most resistance to the erection of a Union workhouse – not until 1848 was the Board of Guardians persuaded to undertake this. However, for various reasons, including a cholera epidemic, it was not until the end of 1850 that plans were agreed upon. The firm Aickin and Capes of Islington designed the new building, situated at the east side of Thomas Street in Merthyr. At a cost of £10,000, it was to accommodate 500. Eventually, in September 1853, the workhouse was opened.

Merthyr was supreme in the manufacture of iron until new manufacturing processes demanded much purer iron. Due to this demand, the population decreased, but Merthyr, being full of fight, made a comeback, and the demand for coal helped further expansion. Sadly, the demand for this commodity collapsed in the 1920s.

The last of the great iron works to be built in Merthyr, Penydarren iron works founded in 1784 by Samuel Homfray, closed in 1859. The original Dowlais Works closed in the 1930s, but production continued at the Ifor Works until 1987.

The iron works at Cyfarthfa employed 1,500 people and was said to be the biggest in the world. In 1847, the management’s refusal to change to steel production brought about the works eventual closure in April 1874. However, in 1879, the works were converted into a steel production plant and reopened in 1882. By 1910, it again, closed. In 1915 it was reopened to produce pig iron and shell steel during the Great War. Finally, in 1919, it closed forever. The dismantling commenced in 1928.

The Merthyr Electric Traction & Lighting Company operated 16 tramcars, running from Cefn Coed to the Bush Hotel Dowlais, and from Pontmorlais Circus to Graham Street. Opened, Good Friday, 6 April 1901 … closed, Wednesday, 23 August 1939. By 1945, production levels had dropped by 40 per cent per man since 1880.

Over the decades, there was a huge capital investment to bring about modernisation. Nationalisation offered a new beginning. Coal was becoming the ‘dirty’ fuel and the coalfield markets collapsed, bringing about the death knell for the coal industry in Wales. Oil and gas put the final nail in the coffin of the coalfields. Coal, once the hero and saviour of the Welsh valleys, had been dropped like a hot potato!

The Aberfan disaster hit Wales like some sleeping Welsh giant awakened in anger at the collapse of the coal industry. At 9.15am on Friday, 21 October 1966 a mining waste tip slid down a mountainside into the mining village of Aberfan, near Merthyr Tydfil, in South Wales.

Children at Pantglas Junior School, situated below the waste tip, had just returned to their classes. Echoes of ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ had hardly faded away from the morning assembly when the slide started.

First to be destroyed in the path of the slide was a farm cottage, killing all the occupants. The mountain was ablaze with sunshine, but visibility in the village was down to a mere 50 metres.

The rumbling of the giant’s stomach could be heard miles away: everything stopped, everyone stopped. Nothing could be seen; soon the Black Death would descend upon the school.

Nothing could be done to stop the slide; a tipping gang on the mountain could do nothing but look on in silent agog. Their telephone line had been destroyed, but even a telephone call would not have saved the loss of 144 lives (116 schoolchildren). The Investigative Tribunal of Inquiry later established that the disaster happened so quickly that a telephone warning would not have saved lives.

Before coming to a rest, the slide had engulfed the school and about 20 houses in the village. Then there was a silence beyond comprehension. Everyone wanted to help, and cars laden with shovels and helpers appeared. Within two hours, all who were to be found alive were pulled free. Nearly one week later, the last of the bodies were recovered. One of the helpers was Malcolm Price.

By 1975, there were only 33,000 coalminers in the South Wales coalfield, and by the 1990s this figure had dropped to the high hundreds. The now-famous picket line strikes of 1973 and 1974, further compounded by the strike of 1984 – 85, put paid to the coal industry. Arthur Scargill became Lord Scargill. The hero who had stood in picket lines and was once arrested had somehow changed into the well-heeled lord.

This once-proud post-industrial area of South Wales had been cast aside, spurned and left to die. The area had been stripped of its once magical assets that were hewn from deep within its bowels by Welsh pitmen.

To add insult to injury, pit heaps were spewed on to the landscape like giant piles of vomit, strewn inconsiderately near the doorsteps of those who were responsible for digging up the innards of the valleys like graveyards.

A feeling of emptiness must have been left in the pit of this sleeping giant’s stomach, as it turned into a forlorn figure. Just like a retired boxer bidding for a return fight and being spurred on by sympathisers to his plight, little chance of a comeback existed.

This sleeping giant was just waiting for any excuse to flex its weary, but not altogether worn-out, muscles, just to show others that it was still capable of putting on a show for the rest of the world to see. The weary giant of the Welsh hills may as well have taken its place next to King Arthur in his resting place, for the Welsh valleys had been raped.

The last great show of Welsh strength was in the 1970s, when Arthur Scargill (Mineworkers’ Union leader) was much more accurate with his predictions than those of Nostradamous ever were. Scargill predicted the end of the pits! Scargill’s prophecies fell on deaf ears. The pits had been forced to close, with no prospects for employment; the money that had once meagrely filled wage packets had dried up.

The economic damage became clear in 1997 when the number of households in Wales with an income of less than £10,000 per annum had reached 50 per cent. Economic deprivation was to make Merthyr Tydfil the poorest area in Wales with 66.4 per cent of households earning less than £10,000 per annum.

In 1998, on a par with England and Scotland, the weekly average gross earnings in Wales were considerably less at £354. Merthyr Tydfil, the Capital of the Valleys, had become a sad sight. The Iron Capital was once the cradle location of the Industrial Revolution; surely it could suffer no further punishment?

Merthyr Tydfil, no longer the Iron Capital, now prides itself on being the commercial and shopping capital of the Heads of the Valleys region. The economic changes – within such a tight-knit community has taken its toll. The loss of heavy industries has long ceased to play a part in the economic life of Merthyr Tydfil. All that is left is an abundance of heavily subsidised heritage sites, which reflect the town’s important industrial past.

Historians may baulk at the interesting historical vistas; tourist offices may admirably point out the doorsteps of some of the loveliest scenery in Wales and the National Park may shout about its Brecon Beacons, but the very people whose veins it runs through are the only ones capable of bringing such a heroic past to life. Tourists cannot ever taste what a Welshman can taste.

The film Twin Town, based on the drug culture in Wales, shattered the idea that Wales was a small part of the world solely defined by its history and its dramatic and beautiful countryside. Illegal drugs and murder vaulted the city life of Swansea to the public eye. Gone was the stereotypical but captivating image of ‘There’ll be singing in the Valleys’. A new challenge to the legendary status of calmness amongst those living in a land once plagued by attacks from all sides of the Welsh borders was to be the start of an insight into what really goes on in Wales.

Enshrined within Malcolm Price is such a Welshman; a man of past and present; a man with a following that could have seen him become a living King Arthur. Just as many of the aforementioned have been perceived as heroes and anti-heroes, Pricey has endured the same label.

Pricey defeats the theory that barbarianism and finesse cannot be rolled into one. The barbarianism was born from his fight to make it in life; his finesse was brought about by his sensitivity to what he was deprived of when he was a child.

Go to Merthyr Tydfil and go cycling, have a picnic, play golf, discover a nature trail, go fishing, visit the large leisure complex, go rambling, take a guided walk, go pony-trekking, play indoor bowls, go sailing, explore Merthyr’s rich industrial history, go windsurfing or take a ride on a mountain railway. But! Until you have met Pricey, you have never taken in a breath of what Wales and its people are all about.

Born in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales, Malcolm Price is now in his 50s. As he sits in the living room of his home on one of the toughest housing estates in Europe, the Gurnos Estate, he matter-of-factly reflects on his tough upbringing.

As a child, his father was very strict and made him go to the boxing gym. At first, Pricey didn’t want to go … his father, though, forced him to attend a couple of times a week. Eventually, the training paid off and he won the Welsh Schoolboy Championship.

Pricey went on to turn pro, having had six fights, winning four and losing two. The losing bouts were to the same man, ‘Big’ Jim Monahan. He was a ‘big bugger’, about 6ft 4in.

One day, Pricey asked his father if he would pick up his coat, which Pricey had left in the Swan pub the night before. When his father got there, the place was a mess! Pricey had been fighting in there the night before … his father wasn’t too happy. Pricey moved in with his gran.

The bar fight led to Pricey serving six months in prison and he was also stripped of his boxing licence. Freedom was to see Pricey take up part-time bouncing on the pub and club doors, which he enjoyed, although this was not his main occupation.

Growing up in Merthyr, people couldn’t help but hear the name ‘Malcolm Price’. Everybody had his or her own stories of him. He was and still is a very well-respected man. Although based in Wales, Pricey is well known to those unfortunate enough to have bumped into him when he was working in England and on the Scottish borders.

Stories about this man’s physical prowess are in great abundance and, up to now, Pricey has refused to cooperate with the many tempting offers put his way by those wishing to tell his story. TV documentary makers have also been disappointed to find a negative response to their pleas for his help.

Since reaching maturity, Pricey has settled down and prefers a sedentary lifestyle, but stories of his fights just keep going on and on and have made him a living legend and a well-respected figure.

In order to grasp the in-depth picture of this man it would be better to relate some of the more violent events, as told in chapter one, in Pricey’s own voice.

Stephen Richards