Читать книгу Mother of All Pigs - Malu Halasa - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

At the butcher shop, Hussein is scrupulous when it comes to the storing of meat. He keeps two refrigerators, one for meat that is permitted and another, much larger, to accommodate forbidden flesh. They are not labeled halal and haram. While he observes no particular dietary restrictions because of religion, he wants to act responsibly—even if he is the only one conscious of the precautions. The halal box is almost empty except for a few pieces of offal. He sells all the freshly slaughtered mutton and goat from the hooks displayed in the window. The other box is filled to capacity, ready for the weekend. He will bring even more ham and sausages under the cover of darkness later tonight, but by the close of business on Sunday, every bit will be gone.

The premises of the dingy butcher shop are washed down daily, water permitting, but the drains are often clogged with fatty grease and give off an unpleasantly pervasive, putrid smell. Hussein lights the gas burner and puts a pan of water on to boil. He can hear his assistant, Khaled, at work in the back. The boy mutters a prayer. This is followed by a frantic scrabbling of hooves against the tile floor, then a spattering that dissolves into a barely audible gurgle as the blood, rich and soupy, drains into an old galvanized bucket. Several muffled thumps—the head and hooves being removed—then a sound like an old oily carpet being torn in half as Khaled peels off the skin. With a liquid slap the entrails pour out, silken and milky. Hussein pictures his assistant rummaging through the pile, like a sorcerer searching for auguries, and picking out the delicacies: the liver, kidneys, and small intestine. The boy inflates the lungs with a series of quick, hard breaths, the time-honored way of testing an animal’s health. He returns to the front of the shop, lays the sheep’s cadaver on the long wooden counter, and, wiping his bloody fingers on his grimy apron, grins stupidly at his boss.

Hussein ignores him and takes a cleaver from the extensive array of well-used hardware that hangs on the wall. There is something deeply satisfying about dismembering a carcass, something irrevocably final about each bone-crushing blow. With each swing of the cleaver Hussein feels his mood improving. Bam! This shows the young delinquent the error of his taillight-smashing ways. Whack! That is for the water truck. Crack! Laila. The next crunch is going to be for Samira and all the trouble she’s been causing them, but at the last moment Hussein changes his mind and once again delivers it as his personal contribution to the struggle against juvenile crime. He works methodically, separating leg from loin, shank from breast, rib from shoulder, venting his frustrations with every stroke.

From his handiwork, he selects two handsome joints and hangs them in the window. Already flies are beginning to gather over the piles of meat, which ooze fat, soft as jelly, onto the counter. The bell over the screen door suddenly rings, announcing the first customer of the day. Hussein forces a welcoming smile.

“Mrs. Habash, good to see you. What will it be today? We have delicious lamb.”

The mayor’s wife is one of the town’s most prominent citizens. She married her cousin and belongs to an ancient tribe, which, like the Sabas lineage, traces its ancestry back to a fortress settlement in the country’s south. Over a hundred years ago their families, and other Christians, were forced to flee northward—the result of a misunderstanding that turned into a sectarian conflict. Eventually they came to a Byzantine city destroyed by earthquakes and established a village that grew into a town. This historic connection is useful to Hussein. It makes it easier to stop by the mayor’s office every couple of weeks with what he calls “a little bite” that is bigger than the crumbs the mayor usually receives. Hussein considers the expense of these friendly consultations another indispensable operating cost. Why should he and his uncle Abu Za’atar be the only ones with their noses in the trough? It is only fair, and no one asks him to do it, but it doesn’t make dealing with the mayor’s wife any easier.

Mrs. Habash dismisses his offer. “I was thinking Issa would like chicken for lunch. You don’t have one in the back, do you?”

Hussein began keeping a few birds in a small coop in the yard after Mrs. Habash told him that she didn’t like going to the market. She feels it’s beneath her dignity to bargain like a falah, a peasant. She prefers to come to Hussein instead and is prepared to pay for the privilege. He calls out, “Khaled, jajeh!” and the boy appears clutching a robust, speckled fowl in his arms.

Hussein is puzzled. Khaled is fond of this particular bird. It is the pick of the flock and the boy gives it special treatment and feeds it extra food. But he can’t say anything in front of Mrs. Habash, so he takes the plump chicken and turns it around for her benefit. She nods in approval. Hussein hands the bird back to Khaled and tells him to prepare it. He urges the boy to hurry—“Assre’!”—more for his sake than for the customer, whom he regards as intrusive. She has probably ordered chicken only so she can gossip while it’s being plucked.

“How’s the family?” She inspects the meat on the counter. “I hear your niece has arrived. I hope she’s not like one of those Arab hip-hoppers.”

“Not at all. Muna is a well-mannered young woman,” he replies, although from what he remembers from last night, he cannot be sure.

“I look forward to meeting her. I would be happy to show her the mosaics after service on Sunday.”

“I’m sure she will enjoy that.” He can already anticipate what’s coming next.

“Perhaps you will join us?”

Long ago Hussein abandoned whatever religious convictions he held. Experience made it impossible for him to carry on believing. Nevertheless, in the past he went to church for the sake of form. As his drinking, disillusionment, and shame increased, he gradually stopped going. Those had been his reasons. His wife insists on attending for the children’s sake, even though it has become difficult. Sometimes people whisper and stare.

Hussein doesn’t want to offend such an important customer. He usually compliments Mrs. Habash’s good taste and even agrees with her when he thinks her opinions are ill judged. His uncle stupidly recommends this as sound business practice.

Hussein instead opts for evasiveness: “Sundays are my busiest days, Mrs. Habash.” It was hard to miss the cars that blocked the main street during the weekend. “All of my customers are Christians anyway. And when I can, I take a moment alone to…” He can’t bring himself to lie outright, so he swallows the word “pray.”

“That’s all well and good,” she sighs, “but commerce is no substitute for worship. Religion anchors our way of life.”

At any moment she is going to remind him that their town was mentioned in the Bible. The Byzantine ruins their families settled on had been an ancient Moabite town where Musa walked and Isaiah prophesized. Like the writing on the side of the tour buses said, VISIT THE LAND OF THE PROPHETS. His father would not have agreed more.

Hussein throws up his hands and wearily concedes, “Can’t argue with that.”

Ignoring him, Mrs. Habash presses on: “I was just telling Issa this morning, even a woman of my considerable years feels the strain whenever I’m near the Eastern Quarter. Mark my words, in a year’s time all us ladies will be wearing hijabs.”

Hussein knows how he is expected to react, but his customers from the Eastern Quarter have been thoroughly decent to him. His van may have been assaulted outside the mosque, but he cannot bring himself to hold a grudge against a religion and all who follow it. His eighteen years in the army taught him to be extremely wary of organized bigotry, and even his two-year special assignment didn’t dissuade him.

Hypocrisy, he reminds himself, is not the exclusive preserve of the pampered and protected who rarely venture beyond family and home. He encountered it in his commanding officers and the secret police, men far more devious than Mrs. Habash. Yet he finds her attitude disquieting. When the numbers of Syrian refugees were low and they were housed with relatives and sympathetic friends in the country, she talked about the importance of solidarity and initiated a few desultory charitable collections. The homeless and bereft who wandered through were nothing more than annoying nuisances, to be pitied rather than feared. Once hundreds of thousands fled over the border and the Eastern Quarter filled with refugees and other migrants, the town’s demographics started changing and Christians, historically the majority, were being outnumbered. Those with the most to lose—people like Mrs. Habash—responded by locking their gates, building their walls higher, and closing their minds.

“Laila hasn’t mentioned any trouble to me,” he admits slowly.

“She will,” intones the mayor’s wife, before complaining, “I just don’t know when the country will return to normal and our town will belong to us.”

Hussein finds Mrs. Habash’s memory highly selective. The town has never been theirs. When their grandfathers and their uncles and fathers—then small boys—first settled, they fought side by side against local nomads over a watering hole. Go back a few generations and someone somewhere is always fleeing or seeking sanctuary with strangers. The entire region has a long history of forced migration. The Syrians are not the first refugees, nor will they be the last.

To divert Mrs. Habash’s attention, he remarks blandly, “I sell so much goat these days—”

“I suppose it’s cheap meat they want for all those children,” she declares. “You can see why they have no money.”

Hussein suddenly feels drained. The morning has already taken its toll. There are too many lines of division between those who have money and those who do not. Hussein sees himself scrabbling in the middle, attempting to grab whatever he can for his family but feeling like a failure most of the time.

Tiredness overrides his better judgment. “All of us like a lot of children, Mrs. Habash, whatever our religion, don’t you agree?”

The mayor’s wife has no offspring; it is the one weakness in her social armor. Hussein doesn’t care that he is being reckless. Lower than refugees are barren women. Everyone agrees: they are without purpose. Christian, Muslim, and Jew alike, they have failed their families and their gods.

Mrs. Habash’s composure instantaneously toughens, as she aims for Hussein’s most vulnerable spot: “By the way, how’s business?”

Before he can answer, Khaled appears behind the counter, his clothes flecked with chicken feathers. He proudly holds up a freshly plucked chicken.

“Wonderful.” Hussein slaps the boy on the back with more enthusiasm than is necessary. He wraps it up, saying, “Fine, Mrs. Habash, just fine,” and hands it to her.

She has already counted out the change. “I only ask because there are rumors, you know.”

As she leaves she holds the butcher’s door wide open. Hussein is sure she is going to remark on the sorry state of the van. So to save himself the embarrassment, he turns his back toward her. Without a ready audience, the screen door slams shut. The sound brings Khaled in from the back with the speckled bird he loves clucking in his arms.

The boy might not be so dumb, Hussein thinks, but his satisfaction doesn’t last long. “Put it back. We’ve wasted too much time.”

Together they pack the mutton into clear plastic bags. The meat is destined for the kitchen of Hussein’s friend Matroub and tonight’s feast celebrating his eldest daughter’s wedding.

Normally Hussein reminds Khaled not to stray on his errands. Today Hussein promises more kindly, “If you hurry they’ll give you ma’amoul.” Khaled’s face lights up at the prospect of semolina cookies. Hussein follows the boy out of the shop and stands on the main street.

The other stores and stalls have opened, as a queue forms outside the bakery. Down the street in front of the pilgrims’ hotel, baseball caps and sun visors board one of the Holy Land tour buses. In front of him, on the other side of the street’s only asphalted section, looms the Marvellous Emporium, a storehouse of untold proportions owned and operated by Abu Za’atar. Hussein wants to go over immediately, to demand his uncle’s attention and pour out his troubles, but the sight of a large truck from Iraq parked beneath the emporium’s neon display stops him. He is all too familiar with Abu Za’atar’s priorities. Drivers bringing loads of potentially profitable goods take precedence over family matters. This truck has an added bonus. It comes from a place known for its American swag—recycled military attire, packaged food beyond its sell-by date, even spare parts from defunct air-conditioning units—which is highly coveted and requires Abu Za’atar’s undivided attention. For it is in the few minutes between refreshment and unloading that a deal is struck. “What a hungry man clings to a full belly gives away” is another of his uncle’s cherished aphorisms.

In the past, Hussein would have been amused. However, since their business venture has become troublesome, he finds himself wondering whether he is just another victim of Abu Za’atar’s avarice. In any commercial transaction his uncle always takes more than his fair share of the profits—that is to be expected. In this one he has managed to avoid both the inconvenience and the social stigma enveloping Hussein. The butcher purses his lips in disgust, mainly with himself. He knows there is no point in being annoyed by Abu Za’atar’s behavior. The new uneasiness in their relationship is not his uncle’s fault. He’s always acted exactly the same way. The problem is that Hussein is finding it harder to accept his relation’s philosophy of profit above all else. Sighing, he retreats back into the shop.

Alone before the morning crush, he crouches down behind the counter and reaches behind one of the refrigerators. Making sure that no one sees him, he surreptitiously extracts an ordinary jar, unscrews the lid, and drinks, long and slow. The neat arak is like fire in his throat, but with the burning comes the savage calm he always finds, temporarily, at the bottom of a bottle. People like Abu Za’atar and Mrs. Habash shouldn’t have a monopoly on a decent future. He wants the same opportunities not so much for himself—it is too late for that—but for his sons. So he did what many would have found inconceivable: he sold his father’s land. Through his own initiative his family resides in a new house. But no amount of money, as his uncle continually reminds him, is ever enough. Hussein glances around again before quickly reaching for the jar and taking one more potent swallow.

From the moment Abu Za’atar showed him the pig, Hussein knew it was not going to be an easy road to riches. He had not really thought any further than the first litter and assumed the piglets would be fattened up for a one-off bonanza sale. Then the business would end. He had not reckoned on the pigs’ natural behavior. No sooner were the young boars weaned than they acquired the mounting reflex. First they tried their mother, then each other, and finally turned their attention to their own sisters. Hussein watched them and began to wonder whether there might be more to the project than he thought.

He knew castration was the best way to ensure that the boars fattened up properly, but he decided to spare two of them from the knife. He left them with their mother and five of their sisters and moved the other thirteen piglets into different pens. The males mated with an uninhibited, libidinous indulgence, reveling in their thirteen-minute orgasms. Fascinated, Hussein timed them on a fancy Taiwanese stopwatch (accurate to one-tenth of a second) borrowed from the Marvellous Emporium. The experiment paid off. At the end of the fifth month, the mother and three of her daughters were pregnant. The rest of the litter was ready for market, but Hussein made a peculiar discovery: he did not have the heart to kill them. It was strange that the son of a farmer, accustomed from an early age to the necessities of slaughtering animals, should be so squeamish; stranger still that a former soldier schooled in the accoutrements of death, from small arms to switchblades, would be incapable of cutting a pig’s throat. Irrationally, he had developed affection for the creatures, born out of respect for their intelligence. There was no question of going to Abu Za’atar; his uncle would not have understood.

Hussein wondered whom he could safely approach with his problem. Then he hit upon the idea of asking the head of the family who rented his father’s mud brick house. Hussein had overridden strenuous objections from Laila when he originally leased the building to one of the oldest Palestinian refugee families, who had arrived in the town during Al Jid’s lifetime. His wife could not understand why he charged so little rent or why, when there was a surplus at the shop, he took gifts of meat to his tenants. It was more than welfare relief on Hussein’s part. By using his father’s house to benefit the less fortunate, he hoped to atone for selling off Al Jid’s beloved land.

Whatever the reason, the family was grateful for his kindness and the husband, a man of about sixty, was more than willing to care for the pigs and get one of his sons to slaughter them for a small remuneration. In this way Hussein took on his first employees, and Ahmad proved to be a capable worker. Nine months and a hundred piglets later, there was more to do than ever before. The retail side of the business was growing, and it looked as though Abu Za’atar’s prediction of easy wealth had not been unfounded.

There remained, however, one apparently insurmountable problem. Hussein scrupulously examined each new litter. He measured each piglet’s weight and size, inspected hooves and tails, and checked eyes, looking for signs. So far he had been lucky, but he knew that his chances of producing another generation without some evidence of inbreeding were very slight. As Laila put it: “Who would want to eat a two-headed beast with six legs?” The gold mine would have closed prematurely if not for Abu Za’atar’s intervention.

The wily emporium proprietor had already made numerous contributions. He provided, at only a fraction above cost, feed, antibiotics, a large and rather noisy freezer, and even an electric prod that Hussein didn’t have the heart to use; but the solution he devised totally eclipsed his previous efforts: through his cross-border contacts Abu Za’atar managed to discover a supply of frozen boar semen. Hussein had not been too keen on the idea—there was something unnatural about it that made him feel queasy.

When the first consignment arrived aboard a Damascus-bound truck, Hussein’s misgivings multiplied. Both the label on the box, which contained the vials of sperm, and the instruction booklet that accompanied it were written in Hebrew. Although there was also a religious prohibition of pork on the other side of the river, it was marketed as basar lavon—“white meat.” At first pork was sold secretly in butcher shops, but when eight hundred thousand Russian immigrants arrived in Israel after 1989, pork was practically on every street corner. To many in Hussein’s town, the very idea of artificial insemination was outrageous enough, but Hussein knew that if the origin of his latest secret were to become public knowledge, then everything he had worked for would go up in smoke.

Abu Za’atar was, of course, thrilled by the prospect of such technological innovation. With his good eye and magnifying glass, he studied the thermometer and other equipment with giddy enthusiasm. Poring over the instructions, he displayed a knowledge of Hebrew that shocked Hussein. As Abu Za’atar assembled the catheter, he airily explained that when no one in the wider Middle East was allowed to say the word “Israel” in public without being arrested, he wanted to learn the country’s language as an act of youthful rebellion. His dream was realized after peace was made between Jordan and Israel in 1994 and cheap Hebrew correspondence courses became available from the Knesset in Jerusalem. Then he brushed aside his nephew’s fears once and for all by declaring, “What’s good for pigs is good for politics.”

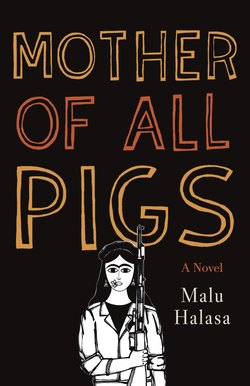

Bolstered by his uncle’s confidence, Hussein reluctantly agreed to give the procedure a try. They restricted themselves to working on the big pig until the method was perfected. The first two attempts were not successful, but by carefully monitoring the signs—a certain redness around the genitals in the presence of one of the boars, a rise in body temperature—Hussein was able to choose the opportune time for the third attempt. The resulting litter was small—eight piglets—but it was clear that the benefits of introducing new blood far outweighed a temporary slowdown. As the litters grew in number and frequency, it was Ahmad who christened Abu Za’atar’s pig. When he groomed her, he whispered to Umm al-Khanaazeer, Mother of All Pigs, how she alone had brought them good fortune.

In any event, there had been a period during the early days when production outpaced demand. This troubled Abu Za’atar, who hated to see waste, particularly if there was a way of turning it into profit. The freezer he supplied was not large enough to contain the surplus, and the fuel costs of running the generator proved to be unnervingly high. So the old man urged his nephew to find some other way of preserving the meat.

Hussein started visiting culinary websites at the town’s relatively new Internet café and found one that detailed various methods of producing ham. He arrived at the farm with two aluminum pots. To ensure against trichinosis, an incomprehensible but nevertheless unpleasant-sounding condition, the meat had to be treated at high temperatures. Hussein was by no means confident in the small fire Ahmad had built, so he compensated by insisting that the meat be steeped in a brine solution and then subjected to several prolonged applications of salt, sugar, potassium nitrate, pepper, and spices, all of which was supplied from the emporium. The result was then dried in the sun. These hams were hard and waxy; Abu Za’atar was not persuaded.

Next, Hussein scoured the Internet for smoking techniques. He left instructions for Ahmad to build a small hut out of corrugated iron while he set about finding the right fuel himself. One site called for oak and beech, woods guaranteed to give the meat a golden hue, but not only were these particular species unavailable, Hussein lived in an area where it was hard to find any wood at all. So he sent Ahmad’s sons to comb the countryside. The assortment of zizphus scrub they managed to collect gave the meat an unhealthy blue-gray tinge and made it smell rank and bitter. “No wonder these bushes produced the thorns in Christ’s crown,” Hussein said, disgusted. He was prepared to give up the project altogether but Abu Za’atar urged him on. Through his infinite contacts, the old man learned of an olive grove in the occupied territories that was about to be destroyed to make way for a new settlement. He procured a truckload of olive wood and, at his own expense, arranged for it to be transported to the farm. Hussein protested about the political implications, but his uncle was unimpressed.

“Surely Al Jid told you the story about the sacred olive,” his uncle explained. “Each leaf bears the words ‘Bismillah al-rahman al-rahim,’ ‘In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.’ If a tree does not pray five times a day, God forsakes it and its fate is to be cut down. Is it my fault the Israelis find every Palestinian olive grove impious?”

Hussein let the gnarled branches weather outdoors to reduce the tannin in the bark and then carefully built a fire in his smokehouse. At last, he was rewarded. The meat, everyone agreed, gave off the aroma of bitter olive, a rich mellow flavor that became instantly popular with the customers. However, consignments of wood arrived too infrequently for smoking to be economically viable. Apart from one man who provided his own juniper twigs and berries—he had a cousin who sent them from Germany, which enabled Hussein to produce a perfectly acceptable Westphalian ham—he was forced to go back to boiling his commercial product. After much trial and error he hit upon the method of coating the cooked hams with honey, anise, and dried nana mint. The real breakthrough came when he made a thick coating of Mother Fadhma’s za’atar spice mixture and a very Arab ham was born.

This required time and space and necessitated the construction of a processing house to keep the meat out of the sun and away from flies. Although Hussein scrupulously never tasted the meat himself, judging only from its density and feel, he was not as satisfied with the texture of the boiled hams as he had been with the smoked variety. So he was pleased that Abu Za’atar was able to arrange for most of the farm’s processed meat output to be exported. Hussein made a point of never asking its destination. If frozen boar sperm and olive wood were easily smuggled across the river, there was no reason a cargo of hams couldn’t go the other way. He just didn’t want to know.

Anything that was not made into processed meat was taken to the sausage machine in the other part of the processing block. Even before the arrival of the machine, Abu Za’atar had insisted that any leftovers too unappetizing to sell be partially cooked, minced with stale bread, and stuffed into intestines. He reasoned that the sheer novelty would ensure sales, and he was right. It was a labor-intensive process by hand. Ahmad’s sons helped out, but it was still too much work. Hussein complained to Abu Za’atar, who responded by turning to his mysterious friend Hani, a former Palestinian fixer and purveyor of the improbable. He had managed to smuggle Umm al-Khanaazeer across four hostile borders, the first of his magic tricks. The second was the unexpected delivery to the farm of an ancient German Wurstmeister.

The sausage machine was a thing of baroque beauty. Pipes, bowls, pistons, mixers, drums, shakers, grips, and pots exuded a futuristic, functional elegance. The power unit looked like it could drive an ocean liner, and when the machine was working it rattled alarmingly. But it performed its task with flawless efficiency. Brain and brawn, ears and jowls, lungs and trimmings, and Hussein’s failed hams were placed in a large hopper above the primary grinding assembly. Once ground, they were mixed in a moving bowl by a rotary knife blade and then transferred to the emulsifier, a large drum where bread, cooked grain, herbs, and spices could be added gradually from their own separate hoppers. When the mixture reached the required consistency, it was forced by a screw mechanism through a small opening into the casings. The skins were washed, scraped, and treated with hydrogen peroxide and vinegar in a different part of the machine. An automatic tying arm twisted the links into two sizes, breakfast or cocktail.

The sausages were more popular than the hams. In fact the only by-product that met with outright consumer resistance was the blood pudding. It simply would not move until Ahmad came up with the novel idea of dyeing the casing turquoise, a color that traditionally warded off the evil eye. After that, it sold steadily. The processing building was a monument to Abu Za’atar’s cheerful dictum that there was a use for “every part of the little piggy.”

Swept along by his uncle’s enthusiasm and seduced by the money he was making, Hussein focused on the positive benefits and suppressed his apprehensions. The morning’s incident outside the mosque caused all the old anxieties to resurface. He would have liked to think of it as an isolated occurrence, but it was clearly more serious than that.