Читать книгу The Secret Messenger - Mandy Robotham - Страница 8

1 Grief London, June 2017

ОглавлениеThe tears come in a torrent – great fat orbs that well up from inside her, catching momentarily on her eyelids. For a second, she feels as if she is looking through a piece of the thick, warped Murano glass dotted around her mother’s living room, until she blinks and they roll down her dried-out cheeks. Ten days into her grief, Luisa has learned not to fight it, allowing the deluge to cascade in rivers towards her now sodden chin. Jamie has helpfully placed boxes of tissues around her mother’s house; much like city dwellers are supposed to be never more than six feet from some kind of vermin, now she is never without a man-size hankie to hand.

Emotional fallout over, Luisa faces a more frustrating issue. The keyboard of her laptop has fared badly from the human cloudburst, and a glass tipped over in her temporary blindness – several of the keys are swimming in salt tears and tap water. It’s too late to mop up the flood – even a consistent jabbing of various keys tells her the screen is frozen and the machine displaying its dissatisfaction. Electronics and fluids do not mix.

‘Oh Jesus, not now,’ Luisa moans into the air. ‘Not now! Come on, Dais – work, come on girl!’ She jabs at the keyboard again, following it up with a few choice expletives, and more tears – this time of frustration.

It’s the first time she’s been able to face opening Daisy, her beloved laptop, since the day before her mum … died. Luisa wants to say the word ‘died’, needs to keep on saying it, because it’s a fact. Her mum didn’t pass away, because that somehow alludes to a serene exit, floating from one dimension to another without rancour, where there is time to put things to right amid crisp white sheets and soft blankets, to say things you want to say – need to say. Even with her limited experience of death, Luisa knows it was short, blunt and brutal. Her mum died. End of. Two weeks from first diagnosis, one week of that in a drug-induced coma to combat the unbearable pain. And now Luisa is the one enduring the inevitable ache of grief. Throw anger and frustration into the mix and you might touch on the myriad of emotions pitching and rolling around her head, heart and assorted organs, twenty-four/seven.

So, Luisa attempts what she always does when she cannot settle, eat, speak or socialise. She writes. Battle-scarred and sporting dog-eared stickers of love and identity, Daisy has been a reliable friend to Luisa in her need to bleed emotions onto a screen page. Often, it’s nothing more than crazy ramblings, but occasionally there is something of worth amid the jumble of words – a sentence or string of thought she might squirrel away for future use or that might well make it into the book one day. The book she will write when she is free of the inane meanderings she currently commits to the features pages of various magazines about the very latest thing in cosmetics, or whether women really do want to steer their own destiny (of course they do, she thinks as she writes – do I really need to spell it out in no more than a thousand words?). But it’s work. It keeps the wolf from the door while Jamie establishes himself as a jobbing actor. But one day the book will happen.

Daisy is party to this dream, a workmate and a keeper of secrets too, deep down in her hard drive.

‘Christ Daisy, what happened to loyalty, eh?’ Luisa mutters, and then feels immediately disloyal to her hi-tech friend. Half drowned in human tears, she may well have reacted in the same way and refused to go on. Daisy needs TLC and time to dry out on top of the boiler. In the meantime, there are pent-up emotions to spill – and for some inexplicable reason a pen and paper is not up to the job. Luisa feels the need to hit something, to bash and clatter at the keys and watch the words appear on screen as if they have magically appeared from somewhere deep inside her, separate to her conscious thinking. Being a child of the computer age, and with her grief threatening to spew, a pen will simply not allow those words to explode from her with venom or unbounded love, or the anger that she cannot contain.

A thought strikes her: Jamie had been up in her mother’s attic the day before to assess just how much clearing out lay ahead of them. As Luisa was tackling the cancelling of direct debits and council tax, he mentioned seeing a typewriter case tucked in the eaves, one that looked fairly old but ‘in good nick’. Would it be worth anything? Or was it sentimental value, he’d asked. At the time, she dismissed it as non-urgent but now her need is greater.

The loft space is like a million others across the globe: a curious odour of old lives dampened and dust that flies up with irritation as you disturb its years of slumber. A single light bulb hangs from the timbers, and Luisa needs to adjust her eyes before objects come into focus. She recognises a few Christmas presents she took pains to choose for her mother – a thermostatic wrap for her aching back and a pair of sheepskin slippers – both of which look to have been barely out of their wrappers before being abandoned to the ‘Not Wanted’ pile. Another reminder of the distance between mother and daughter, now never to be bridged. She pushes the memory away – it’s too deep inside her for now, though it constantly threatens to push through into her grief. It’s therapy for another day. Luisa ferrets around for a few minutes, feeling her frustration rise and wondering if this is the best pastime at this moment, when things still feel so raw. She both relishes and dreads finding a family album where she knows she won’t be able to stop herself from turning the dog-eared pages of so-called happy memories. All three of them on the beach – her, Mum and Dad – fixed Kodachrome smiles all round. In better days.

Mercifully, an object that is not a fat bound book of memories pushes its way out of the gloom. Instead, it’s a grey, moulded case whose shape – square and sloping towards a brown leather handle – means it can only be one thing. It has the look of a life well worn, the scuffs and scratches immediately reminding her of the history Daisy sports on her own casing. There is a distinctive twang as both clasps spring upwards under Luisa’s fingers, and what almost sounds like the escape of a human breath as she lifts the lid. Even under the dim light, she can see it is beautiful – a monochrome mix of black and grey, white keys ringed with a dull metal and glowing bright against the dimness. Luisa puts a tentative finger on one of the keys, pressing it gently, and the mechanism reacts under her touch, sending a thin metal shaft leaping towards the roller. It hasn’t seized up. She notes, too, that there is a ribbon still attached and, even better, a spare, sealed reel tucked alongside the keyboard. The aged cellophane is intact but almost disintegrates under her finger. If fate is on her side, however, the ribbon won’t have dried up.

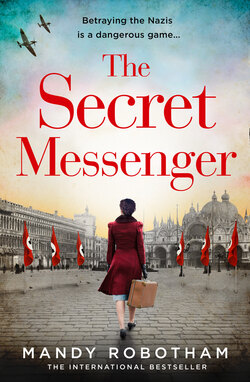

Luisa fixes the lid back down and pulls the case away from a pile of boxes – it’s surprisingly light for an old machine. As she pulls, the lid on one of the boxes slides off, sending a puff of dust in its wake. She turns to replace it, but her eye catches a single photograph, black and white yet sepia-toned with age. It features a man and a woman – their joyful expressions suggest a couple – standing in St Mark’s Square in Venice, the distinctive grandiose basilica behind them, surrounded by a groundswell of pigeons. She recognises her mother in the features of the woman, but not the man. Luisa searches her memory – did her mother and father even mention going to Venice, perhaps for their honeymoon? It looks that kind of photo – the couple seem happy. It’s not how she remembers her parents, but she thinks even they must have been in love once. And yet the photo looks older than that, from a bygone age.

Luisa is aware of her Italian roots, the spelling of her name being an obvious indication. Both of her mother’s parents were Italian, but they died some years ago; her grandfather when she was just a baby, and grandmother in her early teens. She knows very little about their history – her mother would never talk about it – except that they were both writers. She likes to think she has inherited at least that family trait from them.

She flips over the photograph; scrawled in pencil are the words ‘S and C, San Marco June 1950’. Her mother was Sofia, but she was born in 1953, so maybe it’s her grandmother’s face beaming contentment? S for Stella? Perhaps that’s Luisa’s grandpa standing alongside her – Luisa barely remembers him, only a fleeting image of a kindly face. But his name was Giovanni. So who is C? It’s entirely possible he was a suitor before Grandpa Gio, as she knows they called him. Luisa’s curiosity gives way to a smile, her first in days, and the movement of the muscles feels odd. She thinks they look so stylish, he in his high-waisted suit trousers, and she in a neat Chanel-like suit and elegant court shoes, her hair swept in a chic, black wave.

Luisa bends to replace the photograph in the box, but sees that underneath a decaying layer of tissue paper there is more – photographs and paper scraps, some hand-scribed and others typed in an old font, perhaps on the newly discovered machine? To any other curio browser it would warrant a look at the very least, but to a journalist it spikes the senses. There is something about the smell too – the pungency of old dust – which sticks in Luisa’s nostrils and makes her heart beat faster. It reeks of lives lived and history unmasked.

The whole box is heavy and awkward to manoeuvre down the attic stairs and into the living room. In the daylight however, she sees the real treasure come to light. Under a layer of loose type and several browned, brittle newspapers bearing the name Venezia Liberare, Luisa can sense it: a mystery. It’s in the fine sandy texture under her fingers as she gingerly lifts the paper cache – men and women grinning in fuzzy tones of black and white, some she notes casually using rifles as props, or proudly holding them across their chests, women included. Momentarily, she is shocked; in a distant memory, her grandma never appeared as anything other than that – a sweet old lady who dished out cuddles and chocolates, grinning mischievously when she was inevitably rebuked by Luisa’s mother for spoiling her with sweets. Sometimes, Luisa remembers her slipping little wrapped bars when no one was looking, whispering ‘Shh, it’s just our secret’, and she felt like they were part of a little gang.

The typewriter is momentarily forgotten as Luisa picks up each piece, peering at its faded detail, squinting to fill in the gaps of pencil scratchings lost to the years. It hits her squarely then – how many people’s histories are contained in this cardboard box with its sunken edges and corners gnawed at by the resident mice? What might she discover in its depths amid the deceased spiders and smell of mould? What will she learn about her family? She wonders, too, if there is an element of fate in her discovery, if today of all days she was meant to find it – to piece it all together in some order, and in turn glue her recently shattered self back together. For the first time in weeks, she feels not defeated or leaden with grief, but lifted a little. Excited.