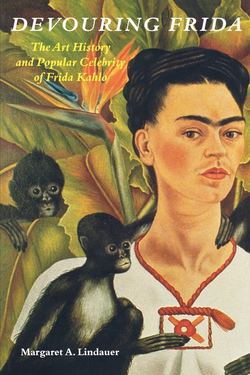

Читать книгу Devouring Frida - Margaret A. Lindauer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Frida as a Wife/Artist in Mexico

ОглавлениеFRIDA KAHLO’S BIOGRAPHY describes her attitude toward marriage to Diego Rivera as progressing from blissfully bourgeois, to vengefully dishonest, and ultimately to comradely complacent. The chronology of her marriage coincides significantly with her development as an artist. When she was considered an adoring wife, her painting was presumed to be a hobby; disillusioned by marital infidelity, her creative work became a career; and concurrent with accepting the particularities of her relationship with Rivera, her painted production came to be considered a commemoration of their personal and political partnership. Kahlo’s self-portraits generally are treated as autobiography, with the artist as author who “wrote” her life story with paint and brush. Thus some paintings are interpreted as shedding light on the emotional development of her marriage and the progression of her professional career. In this chapter, I assert that in postrevolutionary Mexico the social category of artist generally was a masculine one and that Kahlo crossed a gendered boundary between wife and artist. Interpretations of her paintings thereby inscribe gendered social prescriptions. The point of my analysis is not to contest biographic readings of Kahlo’s paintings or to dispute the evolution of her marriage to Rivera but rather to examine how her autobiographical self-portraits offer a vehicle for critical insight into social/historical contexts in which Kahlo negotiated a role between the categories of wife and artist. I demonstrate where paradigmatic gendered boundaries alternately have been inscribed, resisted, and transgressed in interpretations of the paintings. And I consider the ways in which Kahlo’s creative productions signify complex social mediations at the point of production as well as interpretation.

Frida and Diego Rivera (figure 1), produced in 1931 after two years of marriage, generally has been interpreted as a wedding portrait showing that Kahlo embraced the role of a nurturing wife who set up the household, cooked, and delivered Rivera’s meals while he worked, sometimes around the clock, on large-scale commissioned mural paintings. Robin Richmond asserts that Kahlo painted infrequently just after the marriage because, as she traveled with Rivera, she focused on “being his decorative consort and learning how to cook.”1 In her view, “Diego is the huge untameable [sic] bear of a painter, while she sees herself as the tiny-footed, docile dove, hardly able to contain his massive energy in her little hand.”2 Rivera’s “massive energy” can be considered literally to refer to his passionate drive to paint murals. Or it can be considered metaphorically to corroborate Hayden Herrera’s contention that the double portrait foreshadows the nature of their relationship as Kahlo first grew intolerant of, then later assented to, his infidelity.3 Analyses of the composition presume to identify Kahlo’s thoughts and propose that the artist intended to document her private emotions.

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 1. Frida and Diego Rivera, 1931. Oil on canvas, 39⅛″ × 31″. © Banco de México, Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, 06059, México, D.F. 1998. Reproduction authorized by the Banco de México and by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura.

In her discussion of the 1931 painting, Herrera cites a statement that Kahlo made in a 1950 interview: “I let him play matrimony with other women. Diego is not anybody’s husband and never will be.” Herrera suggests that the quotation is relevant to the painting in that Kahlo suspected Rivera’s philanderous nature early in their marriage and accordingly portrayed the couple’s hands “in the lightest possible grasp” to signify that Rivera was “unpossessable.”4 Herrera proceeds, in her description of the painting, to compose character analyses of both husband and wife, arguing that because Kahlo placed the couple’s hands in “the exact center of her wedding portrait,” the painting indicates that the “pivot of Frida Kahlo’s life was the marriage bond.”5 Herrera thereby infers that the painting illustrates Kahlo’s feelings toward Rivera and her marriage and that she narrowed her identity to a strictly domestic persona. Conversely, Herrera describes Rivera in association with his painting career, a significant public role: “As firmly planted as an oak, Rivera looks immense next to his bride. Turning away from her, he brandishes his palette and brushes—he is the great maestro. Frida . . . cocks her head and reaches toward her monumental mate. She plays the role she liked best: the genius’s adoring wife.”6 Herrera’s interpretation emphasizes the distinction between husband and wife. Rivera is active; he not merely holds but “brandishes” his palette and brushes. Kahlo is comparatively passive, her movement tentative or incomplete—she “cocks her head” and “reaches toward” rather than firmly looking and grabbing hold. Herrera’s interpretation is saturated with gender stereotypes. Rivera is “the great maestro”; Kahlo is “the genius’s adoring wife.” Herrera also suggests that Kahlo “has given the general outline of herself and Diego the same shape as the initial carved on Diego’s belt buckle—the letter D,” insinuating that Kahlo metaphorically surrendered her individuality to sustain his.7 Herrera applies a masculine stereotype to characterize Rivera’s self-promoted, exaggerated machismo in terms of both his profession and his libido, and she uses a feminine stereotype to ascribe a domestic role for Kahlo. However, in so doing, she contradicts her own account of Kahlo’s overt challenges to prescribed feminine behavior.

Beginning in 1922, Rivera aggressively sought Mexican government commissions to execute large-scale murals. The mural program was initiated by minister of education José Vasconcelos, who championed having Mexico’s history painted on the walls of public buildings as a means to teach an illiterate, uneducated labor force in urban Mexico.8 At first, numerous artists were employed; eighteen muralists secured commissions, and they, in turn, hired assistant painters and craftspeople. But the government program soon abated during the 1923–24 presidential campaign as politicians explicitly disassociated themselves from the communist philosophies that many muralists promoted. After the election, only Rivera continued to receive commissions. He became internationally acclaimed and was a veritable tourist attraction from 1923 to 1927, as he worked on the three-story patio walls of the Ministry of Public Education Building. Although political and critical debate over the artistic merit and content of his murals consistently grew, his commission was endorsed financially until the murals were completed. Word of his long work days and large-scale projects fed his mythic status as a powerful artist who literally devoted himself to producing art that championed national unity. He incorporated the precolonial past and indigenous peoples into a pictorial narrative of Mexico’s history without backing down to political criticisms of his work. In addition to his artistic virility and political conviction, Rivera’s reputation was based on his ruthless temper, competitive drive, and renowned womanizing. In short, he appeared to epitomize the stereotypes of masculine artist and Mexican machismo by being professionally ambitious, sexually aggressive, and politically outspoken.9 The binary relationship of husband and wife assigns women the opposite qualities, seeing them as passive, faithfully submissive, and domestic.

By Herrera’s account, Kahlo did not embrace these feminine qualities. She was fiercely independent before her marriage to Rivera and had consciously resisted professional and sexual restrictions imposed on middle-class women by social prescription in Mexico. From 1922 to 1925, Kahlo was one of thirty-five women among the two thousand students enrolled in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria and had plans to enter medical school at a time when women doctors were an anomaly. Martha Zamora reports, “Frida enjoyed flouting the rules, whether by a small transgression like wearing bobby socks, prohibited by the school dress code, or by a deviation as extreme as a sexual adventure with an older woman.”10 According to accounts of the artist’s adolescence, Kahlo had little concern for overarching middle-class social mores. As one of the Cachuchas, a small circle of serious students who gathered to debate academic and political issues, she demonstrated a “masculine” interest in national politics. And as an unmarried seventeen-year-old, she was intimately involved with the Cachuchas leader, Alejandro Gómez Arias. But her relationship and her academic pursuits were dramatically cut short in 1925 when she was critically injured in a near-fatal bus and trolley car collision. Her recuperation, slowed by misdiagnosis, began with nine bed-ridden months that foreclosed her scholastic opportunities as medical treatment for her injuries put the family in serious financial debt. While recovering she painted small portraits of friends and family members, some of which she showed to Rivera in 1928, seeking his advice. By then, Rivera was the sole government-sponsored muralist, and Kahlo’s initial conversation with him was an inquiry as to whether, in his opinion, she had sufficient talent to become a successful artist. While the scale and subject of the paintings that Kahlo showed to Rivera were the antithesis of the muralist’s enormous compositions depicting historical, political events, it was well known that Rivera employed several painters to assist in various aspects of his mural production. So Kahlo’s skill might have gotten her a job that would have helped diminish the family’s debt incurred by her medical treatment. Rivera did not hire Kahlo, but he did help her to secure a teaching job. Their relationship quickly became intimate, and they married the following year.

Herrera’s interpretation of Frida and Diego Rivera implies that Kahlo’s marriage profoundly affected her character, causing her to abandon professional aspirations and restricting herself to the repressive social expectations of a devoted wife. Indeed, her marriage unquestionably curtailed a teaching career, and her entire family was economically obligated to Rivera. After their 1929 marriage, Rivera paid Kahlo’s outstanding medical bills and the mortgage her parents had taken on their house in order to pay their daughter’s initial hospital costs. The following year, Kahlo urged her father, “feel free to let me know if you need some money.”11 Thus Rivera’s professional success was crucial for sustaining the middle-class lifestyle of Kahlo’s entire family. While his mural commissions continued steadily, the salary offered by the Mexican government did not compare to proposals that Rivera began to receive from patrons in the United States. So within four months after their marriage, Rivera and Kahlo moved to Cuernavaca where Rivera produced murals for the Palacio de Cortés through a contract with the U.S. ambassador, Dwight Morrow. Rivera subsequently secured commissions from the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts. The couple lived in California for seven months until June 1931 when they returned to Mexico. After their six months in Mexico, Rivera received commissions in Detroit and then New York. They finally returned to live in Mexico in 1933. Clearly, in the first years of their marriage, Kahlo did not pursue employment opportunities as she accompanied Rivera from one mural site to another. She postponed and ultimately declined a teaching appointment by the Department of Fine Arts in Mexico City. This does not necessarily mean that she abandoned professional aspirations in favor of domestic endeavors, but, as numerous interpretation of Frida and Diego Rivera indicate, the double portrait does appear to support Claudia Schaefer’s assessment of women’s presumed artistic roles in postrevolutionary Mexico:

[W]omen were expected to maintain their artistic interests at the level of a trivial, private hobby or to dedicate themselves to the ‘contemptible’ objects of popular culture. Art as a professional occupation and a medium of exchange value was for men; women were relegated to art (craft?) as a domestic pastime. Perfect subjects for women to portray were, of course, what they ‘know best’: children and the home.12

According to Andrea Kettenmann’s assessment of the painting, if Kahlo aspired to a painting profession, she “clearly did not yet have the courage to portray her own self as an artist.”13 In other words, Kettenmann’s interpretation of Kahlo’s painting epitomizes the social context Schaefer described by implying that her role as wife subsumed the artistic endeavors initiated before her marriage. Based on published descriptions of the painting, Kahlo’s marital status, and Schaefer’s characterization of women’s art, it is reasonable to conclude that Kahlo registered prescribed gender roles. But that is not to say that she restricted herself to them. In their study of women writers, Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar investigate ways in which women authors (or artists) use a double code—one that abides by the dominant social order and one that uses the same language but subverts social prescription. Women authors, they argue, “both express and camouflage” strategies in which “surface designs conceal or obscure deeper, less accessible (and less socially acceptable) levels of meaning.”14 Considering Kahlo’s social rebelliousness before her marriage, her academic goals cut off by injury, and her professional pursuits precluded by her husband’s career, the painting, suspiciously, seems to abide by repressive principles. It is extreme in how thoroughly it portrays binary masculine and feminine character traits, suggesting that the subject of the painting is not “Frida and Diego Rivera” (indeed Kahlo did not even call herself Frida Rivera). Rather the painting depicts the artist and her husband in order to produce a painting about binary definition of gendered social positions.

The inscription on the ribbon along the top of the composition begins with a seemingly benign identification, “Aqui nos veis, a mi Frieda Kahlo, junto con mi amado esposo” (Here you see us, me Frieda Kahlo, with my beloved husband Diego Rivera), which prompts reading the painting as a marriage.15 But the subsequent statement, beginning with “pinté estos retratos” (“I painted these portraits”), emphasizes Kahlo as producer, clarifying that while “here you see us,” it is “me Frida Kahlo” who has created this double portrait. Contrary to Kettenmann’s suggestion that Kahlo did not yet have the self-confidence to present herself as an artist, Kahlo stresses in words rather than visual illustration that she is an artist and that she created this portrait of herself with her husband. The text continues: “pinté estos retratos en la bella ciudad de San Francisco para nuestro amigo Mr. Albert Bender, y fué en el mes de abril del año 1931”(I painted these portraits in the beautiful city of San Francisco California for our friend Mr. Albert Bender, and it was in the month of April in the year 1931).16 Naming Albert Bender, an art collector, transforms the painting from merely a domestic portrait to a commissioned work of art, implicitly classifying Kahlo as a professional, paid artist rather than a housewife dallying away her time with a trivial hobby. She may indeed portray “what she knows best”; however, it is not the bliss of domesticity but the binary distinction between masculinity and femininity that assumes women’s omission from professional occupations.

The self-proclamation of the ribbon’s inscription corresponds with visual features alluding to entrenched gender stereotypes. Thus the painting exemplifies Gilbert and Gubar’s argument that women use dominant language illustrating social prescription at the same time that they critique or subvert it. Rivera’s brushes and palette allude to his activities outside the composition and thus outside the marriage. In contrast, Kahlo bears no accoutrements that refer to a social role outside of the composition. But her red shawl stands out, in distinct color contrast to the rest of the painting, which shows an ambiguous interior with light green backdrop and dark, olive green floor. Kahlo’s dress, hair ribbons, necklace, and shoes are also green, linking her with the interior. Rivera’s blue suit and shirt are similar in tone and value and blend into the backdrop. In terms of palette, Kahlo’s bright red shawl, the small red flowers on her shoes, and the minute red dots on the ribbon in her hair deviate from the overall blue-green hues. As a complementary color, her shawl and the accents on her ribbon and shoes are defined by their contrasting color in the same way that the classic male/female dichotomy defines one gender by what it is not. On one hand, her role as woman (wife) is defined by its contrast to the role of man (artist). Hue, tone and accoutrements thereby emphasize that while Rivera is designated by his active, social role outside of his relationship to Kahlo, she is distinguished only by her marital association, the male/female relationship that reserves a creative, public role for the husband. However, because her red shawl distinguishes Kahlo from the rest of the composition, it delineates an ambiguous category apart from her domestic identity as wife to Diego Rivera. And in this enigmatic place, Kahlo proclaims herself a professional artist. Thus her painting is not merely a biographic illustration but also is a social/historical marker indicating the context in which she tacitly proclaimed “I am a painter and I am married to Diego Rivera.” The restrictive characterization “Frida, wife of Diego Rivera,” is implicit in interpretations of the painting and alludes to an unspoken resistance against classifying any woman as a professional artist, an active, virile, masculine role in Mexican as well as the European art history canons. The depicted personae of Frida and Diego Rivera reflect this restriction, but the painting also incorporates personal, historical information relevant to her complex, contradictory roles of wife and artist.

In postrevolutionary Mexico, one of the most significant social expectations of married women was to bear children, and women were understood to carry an intense yearning to procreate and nurture. Kahlo’s creative production is characterized accordingly as a sentimental illustration inspired by the intense psychological agony of not bearing children. For example, Erika Billeter explains that only after Kahlo survived a life-threatening miscarriage did she “find the mode of expression that typifies her thematic pictures.”17 Billeter asserts that in 1932, when Kahlo “lost a baby for the second time,” she realized that “although she can conceive a child, she cannot bear one to the full term. It is as if this realization and the suffering she experienced opened her eyes to a new picture of the world, as if it moved something within her that led to her own vision of pictorial representation. Her suffering created her iconography, and it is tied to her for all time.”18 According to Billeter’s assertion, Kahlo’s paintings tautologically are inspired by the personal events that they document, and they are stereotypically feminine because of their direct relation to the artist’s emotions. Thus Kahlo’s entire creative process is considered to be radically distinct from Rivera’s stereotypically masculine endeavor to create “history” paintings inspired by social and political events. But, contrary to Billeter’s implications, both artists incorporated references to the political context in which they worked. While Kahlo’s paintings do indeed include overt allusions to personal circumstances, they are, as Schaefer argues, “inextricably linked to their historical and social contexts [and] they grow out of a total history, not autonomously in isolation from it.”19 In short, Kahlo’s private life was experienced and understood within wider social contexts that are inscribed alongside personal references in Kahlo’s paintings. Re-viewing her work while making a conscientious effort to discern references and resistances to social codes involves considering Kahlo’s biography but goes beyond an exclusive focus on personal circumstances.

As writers purport that Kahlo’s numerous miscarriages provoked an unfulfilled desire that plagued her throughout her adult life, they interpret the 1932 self-portrait Henry Ford Hospital (figure 2), produced after recovering from a life-threatening miscarriage, as an illustration of Kahlo’s anguish. For example, Herrera explains that Kahlo depicted herself surrounded by “symbols of maternal failure” representing her “knowledge that she would never be able to bear a child.”20 But other authors, though acknowledging Kahlo’s inability to bear children, have questioned the intensity of Kahlo’s maternal desire. She elected to have a surgical abortion in 1930 after Dr. Jesus Marín concluded that the injuries she sustained in the 1925 bus-trolley collision made her physically unable to bear children.21 In 1932, when she was pregnant for the second time, Kahlo wrote to Dr. Leo Eloesser, expressing concern over her physical debility and asking his advice.

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 2. Henry Ford Hospital, 1932. Oil on metal, 12¼″ × 15½″. © Banco de México, Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, 06059, México, D.F. 1998. Reproduction authorized by the Banco de México and by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura.

Given my health, I thought it would be better to have an abortion. I told [Dr. Pratt] and he gave me quinine and a very strong castor oil for a purge. The day after I took this, I had a very slight [case] of bleeding, almost nothing. I’ve had some blood during five or six days, but very little. In any event, I thought I had aborted and I went to see Dr. Pratt again. He examined me and told me that he is completely sure that I did not abort and that it would be much better to keep the child instead of causing an abortion through surgery. [He said] that in spite of my body’s bad shape, I could have a child through a Cesarean section without great difficulties even considering the small fracture of the pelvis, spine, etc. etc.… I am willing to do what is most advisable for my health; that’s what Diego also thinks. Do you think it would be more dangerous to have an abortion than to have a child?22

After reviewing her physical condition and recounting Pratt’s prognosis, Kahlo’s letter implores Eloesser to consider the practical circumstances:

Here [in Detroit] I don’t have any relatives who could help me out during and after my pregnancy, and no matter how much poor Diego wants [to help me] he cannot, since he has all that work and a thousand more things. So I could not count on him at all. The only thing I could do in that case would be to go back to Mexico in August or September and have it there.

I do not think Diego would be very interested in having a child since what he’s most concerned with is his work and he is more than right. Children would come in third or fourth place. I don’t know if it would be good for me to have a child since Diego is constantly travelling and in no way would I want to leave him by himself and stay behind in Mexico. That would only bring problems and hassles for us both, don’t you think? But if you really share Dr. Pratt’s opinion that it would be much better for my health not to have an abortion and to have the child all these difficulties can be overlooked in one way or another.23

Although Kahlo’s letter rationally relays various considerations, conspicuously missing from it is an indication of intense desire to have children. Zamora accordingly suggests that Kahlo “was not obsessed by frustrated maternity,” adding that it was, however, “an idea she encouraged.”24 And Sarah Lowe explains why Kahlo would have encouraged it: “in the context of Mexican social codes … having a child, indeed … motherhood itself, not only was an indispensable aspect of femininity but virtually defined womanhood.”25

Thus the presumption that Kahlo desperately wanted children, implicit in Herrera’s analysis of Henry Ford Hospital, corresponds to a social, symbolic significance of motherhood in Mexico. Motherhood was entangled in Mexico’s postrevolutionary concern for social stabilization. During the ten years of revolution, 1910 to 1920, Mexico was economically, socially, and politically chaotic. The country saw ten different presidents, most of whom began their tenure after a violent overthrow of the previous administration. The 1920 election of Álvaro Obregón brought relative calm and an administration intent on constructing national unity and economic equilibrium despite competing ideological forces.26 But even during Obregón’s presidential administration, conflicting reconstruction strategies invited ideological and political competition. Much of the industrial infrastructure had to be repaired or rebuilt. There were demands for land and labor reform that would more broadly distribute ownership and profit. Extensive illiteracy, lack of mass communication systems, and a nascent education program complicated the goal of integrating the country’s diverse urban and rural populations into an informed democratic citizenry. Stabilization was a long, arduous process, and the problems that Obregón faced in 1920 plagued presidential administrations through the 1930s.

In the midst of chaos and instability, the mythically steadfast family became a pervasive symbol for stabilizing the country. In the mythic family, the ideal woman excelled in the domestic sphere, nurturing the family, while the paradigmatic man attended to public affairs.27 Ironically, the gendered stereotypes of husband and wife reinscribed European mores fervently promoted during Porfirio Diaz’s 1876 to 1910 presidency, against which revolutionary factions united in rebellion. Although the rhetoric of postrevolutionary nationalism spurned the Profirian era’s embrace of European values and material culture, it also espoused the prerevolutionary social codes for gender distinction articulated through family stereotypes. The symbolism of a paradigmatic husband/father, center of both family and society, with a wife/mother who provided all of his domestic needs, including a throng of children submissive to his paternal direction, comprised an analogy for a society that submitted to a paternalistic national government.28 Repressive gender restrictions were not prime factors contributing to the rebellions that comprised the Mexican Revolution. But women’s participation on battlefields and in political arenas marked a significant departure from Porfirian-era gender mores for the middle class. Female soldaderas fought violent, bloody battles and championed political causes to end economic, physical, and cultural exploitation, thereby blatantly disregarding prerevolutionary gendered codes that presumed women’s absence from active political combat. Thus the postrevolutionary reinscription of the bourgeois family as a hallmark of a stable society sharply contrasts the liberation from the strict gender dichotomy that the revolution precipitated.

Domestic roles were promoted, in part, by mythologizing women’s motivations for appearing on the revolution’s battlefields. After 1920, accounts of the revolution celebrated women as loyal companions and helpers rather than fierce fighters. Maria Antometa Rascon argues that “bureaucrats who write up the history of women’s participation in social movements . . . [emphasize] their subordinate condition, their sacrifices, their self-denial and the support they provide for their husbands’ struggles.”29 Fictional narratives such as Rivera’s 1928 “Distributing Arms” panel of the Insurrection Ballad of the Proletarian Revolution mural at the Ministry of Public Education (figure 3) diminish the active heroic significance of the soldaderas by casting women in passive or subordinate roles. Rivera’s mural panel anachronistically portrays Kahlo (who was three years old when the revolution began) distributing arms to revolutionary soldiers. Rivera’s painting places Kahlo within a political arena; however, it is an agenda that is engendered. Rivera portrayed Kahlo in a secondary capacity, not actively orchestrating or participating in violent fighting, but equipping men with weapons. As Jean Franco argues, historical and fictional narratives that reduce women’s revolutionary activities to the domestic ones of giving birth and rearing a family on the battlefields simultaneously herald men as aggressive redeemers. Postrevolutionary discourse associated masculine “virility with social transformation.”30

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 3. Insurrection Ballad of the Proletarian Revolution, “Distributing Arms.” Mural by Diego Rivera, 1928. Ministry of Education. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Litteratura.

Rivera’s mural represents one way in which gender dichotomy was promoted—women’s roles were depicted as those which serve men’s. Another way that gender distinctions were articulated was through symbolic demonstration of the consequences that “overzealous” women faced when they adopted masculine behavior. Franco argues that the “broken family, the cult of violence, and the independent ‘masculinized’ woman” were primary subjects in postrevolutionary films; and typical narratives focused on the transformation of wayward subjects “into a new holy family in which women accede voluntarily to their own subordination not to a biological father but to a paternal state.”31 The family was the ideological site where the passive-female/active-male distinction was entrenched, with the stereotypic Mexican wife/mother not only ancillary to the absolute authority of the husband/father but also to the nation. Within these narratives, male and female roles in relation to family and nation were constructed to appear remarkably stable and unaffected by political upheaval before, during, and after the revolution. The only fluctuation was the family’s environment, from home, to battlefield, and back home again, with women faithfully accompanying their husbands in their public duty. Thus the distinction of social roles according to gender lines was formulated as an overriding constant component of early-twentieth-century Mexican society. On the feminine side of the boundary between domestic (feminine) and public (masculine) roles, caretaking responsibilities were configured not merely as a feminine function but a social duty, and motherhood amounted to much more than personal or biological fulfillment. Indeed, despite women’s political and military involvement in the revolution, the 1917 Constitution did not grant them the right to vote, on the pretext that their contributions to revolutionary causes were not an indication of political aspirations. One report to the Constituent of Congress claims that “Mexican women have traditionally concentrated their activities on the home and the family. Women have no political consciousness and do not feel the need to participate in public life, as is shown by the absence of any collective movement to attain this end.”32

Kahlo produced Henry Ford Hospital amid this mythology, which is echoed in assumptions that Kahlo was devastated by her lack of children. Interpretations inscribing postrevolutionary symbolism of the family project an overwhelming despair onto Kahlo, thereby demonstrating the tenacity of the family mythology. As Tomás Almaguer argues, the “Mexican family remains a bastion of patriarchal privilege for men and a major impediment to women’s autonomy outside the world of the home.”33 With the hospital bed and miscarriage depicted in an open, outdoor space, Henry Ford Hospital exaggerates the correlation between private incident and public discourse. When the painting was first exhibited, its title was The Lost Desire. Though rarely discussed as an aspect of the painting, the “lost desire” to which the former title refers implicitly has been assumed to refer to Kahlo’s longing for children. However, another association with a “lost desire” is the less-often-invoked charge that Kahlo lacked maternal longing. This is a more serious accusation in that the artist rejects social prescriptions for enacting mythic stereotypes relating national, paternal desire to a gendered, social hierarchy. Suspicion about Kahlo’s “desire” is implied in accounts of the miscarriage in which she is held responsible for the baby’s death. Ella Wolfe suggested that Kahlo could have carried a child to term if only she had obeyed the doctor’s instructions to stay in bed for six months.34 And Richmond explains: “Having finally decided to try to rest and keep the baby, Frida’s behavior seemed designed to sabotage her deepest wish. Diego had come around to the idea of a child. He tried to … persuade Frida to have complete bed rest. She took driving lessons instead.”35 Thus, with a husband who had “come around” and was urging Kahlo to restrict her behavior appropriately, she alone is blamed for their lack of children and held culpable for the aborted family. Kahlo’s miscarriage connotes both a personal tragedy and a public loss that could have been prevented. Symbolically Rivera is cast as if he accepted his individual responsibility to build a stable postrevolutionary society through the propagation of children. Kahlo accordingly is cast as a traitor who recklessly put her individual whims before her social responsibility. No matter how much she may have wished for a child (as alleged), her actions sabotage the postrevolutionary social directive.

In Herrera’s analysis of Henry Ford Hospital, Kahlo suffers the consequences of her socially subversive behavior. Herrera notes the juxtaposition of the hospital bed and the Ford factory in the background and explains, “the world outside … functions cleanly and efficiently; Frida on the other hand is a wreck.”36 With the assertion that Kahlo depicted herself as physically and emotionally disabled, Herrera implies that Kahlo recognized her own culpability. Furthermore, she suggests that the distance between Kahlo’s bed and the factory, where Rivera worked on sketches for his Detroit murals, is an analogy for the distance between his commitment and her lack of commitment to social prescription delineated according to gender dichotomy. Herrera explains that one reason Kahlo weeps in the painting is because Rivera has abandoned her in order to return to his work, and his absence is exacerbated by the barrenness of her womb, tangible evidence of her selfish irresponsibility.

Ironically, while strict social codes are embedded in the recollections of Kahlo’s miscarriage and interpretations of the paintings, the relevance of broader social contexts tacitly is negated when writers insist that Kahlo focused exclusively on illustrating her emotional responses to personal tragedies. Kettenmann attributes the artist’s painting style and compositional elements to Kahlo’s purported intention to illustrate her private life:

Although the … [objects] are rendered in accurate detail, true-life realism is avoided in the composition as a whole. Objects are extracted from their normal environment and integrated into a new composition. It is more important to the artist to reproduce her emotional state in a distillation of the reality she had experienced than to record an actual situation with photographic precision.37

Herrera also restricts consideration of compositional features to personal denotation based on statements by the artist and her colleagues. Citing Kahlo’s comments from a 1939 interview conducted by art historian Parker Lesley, Herrera explains the meaning of objects depicted in the painting: the pelvic bone represents doctors’ theories that injuries sustained in the 1925 bus-trolley accident prevented Kahlo from carrying a child to term; the orchid was a gift from Rivera; the snail represents the agonizingly slow pace of the miscarriage; and the infant stands for the aborted fetus, the “ ‘little Diego’ she hoped it would be.”38 Herrera’s direct correlation between the depicted miscarriage and the actual miscarriage is not without basis, as it is supported by Kahlo’s explanation. But artists’ statements also must be considered in relationship to social, historical contexts. As Schaefer argues, social directives dissuaded women from speaking critically about their lives: “If a woman spoke up, she was no longer dependent on others, nor on the interpretation and control of social reality, and consequently she was a threat to the status quo.”39 Kahlo’s description of the painting, as related by Lesley, clearly corresponds to social expectations, but it does not necessarily correspond to Kahlo’s attitudes toward motherhood.

David Lomas refers to broader social discourses that may have compelled Kahlo to publicly explain her paintings as nothing more than personal illustrations, and these also would have accounted for the fact that Kahlo’s contemporaries held her responsible for the miscarriage. He begins his analysis of the painting by noting, “In the culture to which Kahlo belonged miscarriage was a source of shame: the abject failure of a socially conditioned expectation of motherhood.”40 Lomas regards Kahlo’s use of personal circumstance as a vehicle through which she articulated not merely personal feelings but broader feminine experiences that go beyond the biological. The painting refers to socialization structures that delineate paradigmatic gendered characterizations. Thus the disjunctures and discontinuities of Kahlo’s painting represent her personal position in affiliation with, yet distinct from, the mythology of motherhood. On one hand, the painting exemplifies social prescription in ways that Herrera and Kettenmann discuss: the artist depicted herself as emotionally distraught over her lack of children, abandoned in a landscape devoid of human companionship, and haunted by her aborted son. On the other hand, the painting also challenges social directive by making explicit the limited realm (motherhood) in which women could be socially esteemed. The baby is at the center of the painting, analogous to a child as the central, necessary feature for completing the patriarchal family. Significantly Kahlo depicted a baby boy who would have inherited the masculine privileges of patriarchal society but who also represents the perpetual regeneration of the patriarchal nation. Without children, the wife’s subordination and the husband’s command are incomplete, and the woman floats in an enigmatic space.

Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen articulate an approach to interpretation that moves away from identifying aspects of the painting as signifiers for Kahlo’s personal life and private emotions. They argue that Kahlo “uses the device of the ‘emblem.’ In Henry Ford Hospital, her body on the bed is surrounded by a set of emblematic objects, like those surrounding the crucified Christ in an allegory of redemption.”41 There is a significant difference between thinking about the objects in the painting as personal references, “symbols of maternal failure,” as Herrera proposes, or as emblems, “graphic signs which carry a conventional meaning, often in reference to a narrative subtext … or a common set of beliefs.”42 As personal referents, the bloody hospital bed stands as tangible evidence of her barren womb. The medical world, symbolically represented by the autoclave and medical models of a female torso and pelvic bone, diagnosed Kahlo’s responsibility for the miscarriage. However, if her miscarriage is considered a narrative subtext, then interpretation can incorporate broader social issues. As Lomas explains, medical practice “straddles the border of private and public,” enforcing public gender codes through an analysis of private culpability.43 Lomas further suggests that the Ford Complex in the background invokes capitalist standards. Thus Kahlo’s medical miscarriage is presented alongside measures of production and profit in which the “birth and death in miscarriage adds up to nothing.”44 In relationship to postrevolutionary issues, the miscarriage neither counts toward the perpetuation of family nor promotes symbolic stabilization. As Lomas explains, Kahlo’s detailed rendering of objects within an imaginary scene including a hospital bed on an industrial landscape is an “awkward disjuncture between two pictorial modes—schematic and naturalistic,” which can, given critical analysis, “render visible a blindspot” or unspoken narrative inscribed in cultural discourse.45

Her childlessness was a tangible social dysfunction, the first transgression that marked Kahlo’s unstable social status. As Kahlo became defined as a childless woman and an artist, she crossed gender boundaries, and interpretations of her paintings exemplify the tension under which social codes were imposed and resisted. The consistency with which writers describe Kahlo’s maternal longing and despair, alongside the absence of any expression in Kahlo’s letters of intense desire, suggests that she may have orchestrated a false notion that she yearned for children. Although hardly surprising given social expectations, her duplicity complicates the strict binary distinction between men and women in which motherhood defines woman, because it suggests that Kahlo covertly rejected an esteemed stereotypic female role for herself. According to a strict binary interpretation, if Kahlo does not crave feminine fulfillment, she must, by default, desire a masculine position. This would have been particularly unsettling to a society in which, as Almaguer suggests, “lines of power/dominance [are] firmly rooted in a patriarchal Mexican culture that privileges men over women and the masculine over the feminine.”46 Overt resistance against strict binary roles was extremely difficult in a culture that viewed, as Matthew Gutmann notes, las mujeres abnegadas (self-sacrificing women) as the popular opposite from machismo.47 During the 1920s and 1930s, women had little opportunity to effect political cultural changes, despite their organized fight for women’s rights, including the right to vote.48 Thus resistance to strict gender codes could effectively be enacted only in their personal lives. However, if a woman resisted actively enough, foregoing passive subordinate behavior, she fell into another category—the fallen woman, a potential traitor whose resistance is associated with an active, aggressive sexual drive.

According to Lesley, Kahlo explained that the orchid represented in Henry Ford Hospital was a flower that Diego gave her while she was in the hospital, but it also represented “the idea of a sexual thing.”49 Merely incorporating a subtle representation of sexuality was not in and of itself a serious transgression, but reports of Kahlo’s blatant acknowledgment of sexual connotations cast suspicion on her willingness to abide by social codes. Bertram Wolfe described Kahlo’s masculine manner. She chain-smoked cigarettes, drank to excess in public, and used “the richest vocabulary of obscenities … known [of] one of her sex to possess.”50 In other words, her behavior was resolutely unfeminine and thereby an overt challenge to gender dichotomy. This sort of challenge was typical of the “woman resistor” or fallen women and, Franco argues, was a significant element in social mythologies told through popular, postrevolutionary fictional written and filmed narratives.51 The fallen woman narrative ended either in a moralizing portrayal of an irretrievable psychological decline (for which only the woman herself was to blame) or in the jubilant recovery of a woman reentering the dominant order. Both of these themes are present in Kahlo’s life during the mid-1930s, at which point it became clear that she could not be “contained” within the category “mother,” and during which her feelings toward marriage are characterized as having transformed from blissfully domestic to vengefully dishonest. Biographies typically identify two primary catalysts for the transformation—Kahlo’s insistence that she and Rivera return to live in Mexico in 1933 and her despondence over Rivera’s infidelity. Both are relevant to gender stereotypes in that Kahlo transgressed and Rivera exalted in their respective female and male paradigms.

Kahlo’s letters indicate that she was aware of, and accepted, Rivera’s extramarital affairs, which began perhaps as early as their wedding day. (Herrera reports that Rivera got excessively drunk and disappeared for two days, during which he probably was in the bed of another woman.) In Mexico, Rivera’s sexual “conquests” were publicized, accepted, and expected in a society in which machismo is an overarching, constructed measure of masculinity. As Marvin Goldwert argues, “From adolescence through his entire life, the Mexican male will measure virility by sexual potential.”52 Although Kahlo may not have liked her husband’s philandering, she purportedly tolerated Rivera’s promiscuity and the publicity surrounding it until he became sexually involved with her sister Cristina. Upon discovering the affair, Kahlo moved into an apartment in Mexico City. Her disillusionment with marriage is apparent in a letter she wrote to Ella and Bertram Wolfe during the separation: “I had trusted Diego would change, but I can see and know that it is impossible; it’s just a whim on my part. Naturally, I should have understood from the beginning that it will not be me who will make him live in this way or that way, especially when it comes to such a matter [as his sexual liaisons with other women].”53 In the same letter, Kahlo reflects on her life as the wife of Diego Rivera, succinctly characterizing the social position of the subordinate wife:

First, he has his work, which protects him from many things, and then his adventures, which keep him entertained. People look for him and not me. I know that, as always, he is full of concerns and worries about his work; however he lives a full life without the emptiness of mine. I have nothing because I don’t have him. I never thought he was everything to me and that, separated from him, I was like a piece of trash. I thought I was helping him to live as much as I could, and that I could solve any situation in my life alone without complications of any kind. But now I realize I don’t have any more than any other girl disappointed at being dumped by her man. I am worth nothing, I know how to do nothing; I cannot be on my own.

My situation seems so ridiculous and stupid to me that you can’t imagine how I dislike myself. I’ve lost my best years being supported by a man, doing nothing else but what I thought would benefit and help him. I never thought about myself, and after six years, his answer is that fidelity is a bourgeois virtue and that it exists only to exploit [people] and to obtain an economic gain.54

Clearly Kahlo was devastated by the affair and questioned the personal value of her domestic devotion. Rivera accordingly is castigated for his callousness, as well as his infidelity, in Kahlo’s biographies. However, she also is held accountable for Rivera’s affair with her sister, for Herrera asserts that Rivera may have had the affair with Cristina because he blamed Frida for their leaving the United States in 1933.55 Herrera’s interpretation intimates the social, gendered context that contained the moralizing consequences awaiting the wife who dominates her husband, “forcing” him to relocate and thereby not practicing “proper subordination.” Kahlo crossed an unspoken boundary that distinguished pervading gender paradigms when she actively made demands; she was no longer passively subservient and therefore suffered the consequences—her husband’s affair with her sister. This narrative, consistently recounted in biographies of Kahlo, parallels remarkably the moralizing films and published fiction Franco analyzes. There undoubtedly are aspects of “truth” embedded in the biographies, but the point is not to distinguish “truth” from moralizing fiction but rather to recognize the pervasiveness of cultural stereotypes and mythologies in order to question whether Kahlo’s paintings really promote social prescription as thoroughly as some biographies imply.

Kahlo and Rivera soon reunited, but Kahlo no longer appeared to embrace conventional bourgeois ethics regarding marriage and sexuality, for both she and Rivera had intimate, sexual relationships outside their marriage. Herrera attributes Kahlo’s sexual infidelity to extreme disillusionment and considers her pronounced sexual drive a conscious retribution against Rivera. Herrera suggests that in 1935 Frida had affairs with Isamu Noguchi and mural painter Ignacio Aguirre primarily because Rivera had been unfaithful.”56 Zamora notes, “some [of Kahlo’s] friends believed these dalliances were merely in retaliation for Diego’s transgressions; others felt they were expressions of her own sexual amorality.”57 Whether vengeful or sincere, Kahlo implicitly is cast as amoral, despite the spousal agreement; but it was not necessarily her sexuality, rather her active pursuit, that was most socially transgressive.

Comparing Rivera’s Today and Tomorrow: Modern Mexico mural in the National Palace (figure 4) to Kahlo’s painting A Few Small Nips (figure 5), both completed in 1935, demonstrates a double standard and contradictory perspectives regarding sexual promiscuity and infidelity. Franco argues that Rivera’s Today and Tomorrow: Modern Mexico characterizes the limited extent of women’s liberation in postrevolutionary Mexico.58 Kahlo and her sister Cristina are depicted as teachers, but there are significant differences between them. In the 1920s and 1930s, teachers and caretakers, “surrogate mothers,” were respectable social roles for women, particularly unmarried middle-class women, signifying participation through appropriate political service in postrevolutionary Mexico. Vasconcelos characterized women who carried out literacy programs in rural areas as national heroines. Despite the inclusion of women in the nation’s social reconstruction, as Franco points out, the teaching missions “placed women in a position that was rather similar to that of the nuns in the colonial period serving their redeemer. They were expected to be unmarried and chaste, they had little expectation of rising in their profession, and motherhood was still regarded as woman’s supreme fulfillment.”59 In the mural Rivera casts his wife, who is unable to realize “woman’s supreme fulfillment” through bearing children, as a teacher, the next best, socially respectable role. She rests her hands on a boy’s shoulder in a gesture of care and encouragement while, with the other hand, she helps him hold his book. Frida as teacher nurtures a child’s education, thereby guiding him toward a productive, active public role. Cristina also holds a book, but her attention, and the book, are directed toward the viewer rather than the children next to her. Remarking on the fact that Rivera was married to Frida and sexually involved with Cristina during the production of this mural, Franco asserts that the image presents a social message for women as well as “a male polygamous fantasy” suggested by Cristina’s “voluptuous look and upturned eyes of a woman in orgasm.”60 While appearing to demonstrate women’s professional “liberation,” Rivera’s mural also promotes an idealized masculine virility—both sexual and social—by depicting two women, one socially marginalized and the other sexually available. Women may have enjoyed a certain level of professional status and some loosening of sexual mores, they were not free of the passive/active axis that renders the woman professionally subservient and sexually submissive to the active male.

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 4. Today and Tomorrow: Modern Mexico. Mural by Diego Rivera, 1934. National Palace, Mexico City. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura.

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 5. A Few Small Nips, 1935. Oil on metal, 15″ × 19″. © Banco de México, Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, 06059, México, D.F. 1998. Reproduction authorized by the Banco de México and by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura.

Kahlo’s painting A Few Small Nips depicts a socially resonant attitude toward actively promiscuous women. The painting is a bloody depiction of a woman with multiple stab wounds, lying on a bed while her attacker, splattered with blood and still holding a knife, stands over her mutilated body. The title was taken from a newspaper report of a man who brutally murdered his unfaithful wife. Upon his arrest, he explained, “But I only gave her a few small nips.”61 Kahlo’s preparatory sketch for the painting—in which the man explains, “My sweetie doesn’t love me anymore because she gave herself to another bastard, but today I snatched her away, her hour has come”—explicitly indicates that infidelity precipitated the murder.62 The woman wears one shoe with stocking and garter pushed down her leg. Her erotic accoutrements hint at the woman’s transgression, which crosses a boundary distinguishing a sexually passive woman from the promiscuous whore, the most culturally stigmatized female in Mexican society. In fact, Herrera characterizes the man as stereotypically macho and the woman a la chingada, a term which, on one hand, simply refers to her victimization.63 According to Octavio Paz the feminine noun la chingada is related to the verb chingar:

The verb is masculine, active, cruel: it stings, wounds, gashes, stains. And it provokes a bitter resentful satisfaction. The person who suffers this action is passive, inert, and open, in contrast to the active, aggressive, and closed person who inflicts it. The chingón is the macho, the male; he rips open the chingada, the female who is pure passivity, defenseless against the exterior world. The relationship between them is violent and it is determined by the cynical power of the first and the impotence of the second.64

On the other hand, la chingada is a complex cultural classification that suggests a woman’s innate culpability, associated with her sexuality, as the base cause of European penetration and domination of precolonial Mexico. La chingada literally translates as “the fucked one” and refers, in Cherríe Moraga’s words, to the “sexual legacy” of betrayal “pivoting around the historical/mythical female figure of Malintzin Tenepal,” the Aztec translator and mistress to Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés.65 Moraga explains, “Upon her shoulders rests the full blame for the ‘bastardization’ of the indigenous people of Mexico. To put it in the most base terms: Malintzin, also called Malinche, fucked the white man who conquered the Indian peoples of México and destroyed their culture.”66 Ironically, as Moraga notes, Malinche “is not … an innocent victim, but the guilty party—ultimately responsible for her own sexual victimization.”67

Although Herrera refers to the woman depicted in Kahlo’s painting as la chingada, she does not discuss the cultural signification of Malinche’s sexuality and its association with deception, which is presumed to be inherent in all women. Analogous to Malinche’s guilt as a traitor to the Mexican people, Herrera implies Kahlo’s guilt in Rivera’s affair with her sister (by supposing that because Kahlo assumed the active role of directing Rivera to return to Mexico, she precipitated the affair). Herrera thereby suggests that A Few Small Nips was produced in response to the affair. Richmond also alleges that the painting refers to the emotional pain Kahlo suffered due to Rivera’s callous infidelity, and she proposes that the painting represents reversed gender roles in its “graphic expression of the anger she wishes to vent on his … body.”68 Richmond’s words exemplify the paucity of available ways to express female aggression and demonstrate the currency of Malinche mythology. In other words, Richmond implies that Kahlo set out to depict her own anger toward Rivera yet reversed the gendered roles so that, in the painting, a man represented Kahlo’s anger and a woman represented the object of her anger. Thus, according to Richmond’s interpretation, Kahlo’s painting abides by the paradigmatic gender characterizations in order to represent forbidden sexual infidelity. It is significant that the painting itself contains absolutely no visual references to Rivera or Kahlo yet is considered to represent Kahlo’s assumed retribution fantasy against Rivera. No interpretation considers the painting’s potential as a visual explication of repressive social mores that delineate the paradigmatic male and female, distinguished not only in terms of sexual activity but also according to active versus passive behavioral roles. Although unacknowledged, Malinche (la chingada) mythology provides the symbolic cultural basis for reading the gender role reversal, and Richmond’s description of A Few Small Nips demonstrates that ideology is inscribed in interpretation particularly when Kahlo was perceived to be resisting or transgressing highly invested social boundaries.

By 1935, when Kahlo produced the painting, a spirit of fervent nationalism imbued the drive to regain political and economic control of Mexican culture and industry that, according to la chingada mythologically, initially had been lost to Europe because of Malinche’s betrayal. Thus there is an implied relationship between women’s sexuality and national betrayal, one that remained significant to postrevolutionary discourses in which a woman’s maternal role was associated with national stability. The obverse female role, the fallen woman who was actively promiscuous, thereby symbolized a traitor to postrevolutionary nationalism and implicitly represented the nation’s vulnerability. Within these powerful cultural codes (largely unarticulated in biographies of the artist), Kahlo and Rivera agreed, after their 1935 reconciliation, that neither necessarily would be monogamous. Beyond their mutual understanding and personal perspectives toward sexual mores, Kahlo’s extramarital relationships had an entirely different cultural connotation than Rivera’s. Therefore, it is not surprising that biographies of Kahlo (and Rivera) consistently remark that she was far more discreet in her intimate affairs. Characterizations of Kahlo’s conduct allude to the fact that while Rivera’s liaisons corresponded to stereotypic masculine virility, there was not an equivalent social category in which it was permissible for a woman to engage actively in extramarital relationships. As María Herrera-Sobek explains, Malinche mythology acts as an albatross, and the sexually active woman is cast alongside “the whore who sells her people to the enemy.”69

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 6. Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Leon Trotsky), 1937. Oil on masonite, 30″ × 24″. © Banco de México, Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, 06059, México, D.F. 1998. Reproduction authorized by the Banco de México and by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura.

Discussions of Kahlo’s 1937 Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Leon Trotsky) (figure 6) invariably include remarks regarding Kahlo’s cautious breach of social/sexual principles. By Kahlo’s own account, she had a brief affair with Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. In January 1937, Trotsky and his wife, Natalia Sedova, arrived in Mexico, their political asylum granted by President Cardenás largely due to Rivera’s persuasion. Trotsky and Sedova lived in Kahlo’s family home in Coyoacán for two years until the friendship and political alliance between Trotsky and Rivera broke down. (Kahlo and Rivera lived in their San Angel home at the time.) During these two years before the rift, and particularly in the months immediately after January 1937, the two couples socialized frequently, often among other artists and political activists. During social gatherings, the politics of revolution and art were debated, though historical accounts include only the male voices, implying, by omission, that Sedova and Kahlo either did not have political opinions or did not engage in political discussions. The women reportedly did not converse with each other because Sedova did not speak Spanish. Sedova and Trotsky separated for a number of weeks in July 1937, by which time, Jean Van Heijenhoort reports, the brief affair between Kahlo and Trotsky had ended.70 Trotsky asked Kahlo to destroy his letters, and they shared a concern that Rivera not learn of the affair. Kahlo’s biographers consequently suggest that the inscription on Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Leon Trotsky), which begins, “Para Leon Trotsky, con todo cariño, dedico ésta pintura” (For Leon Trotsky with love, I dedicate this painting), indicates Kahlo’s unabated affection suppressed by her own pragmatic discretion and fear of Rivera’s temper, which led her to destroy all other evidence of the affair. Thus the painting constitutes the only tangible testimony of the briefly amorous relationship.

Noting that the painting was produced and given to Trotsky after the affair had ended, Herrera submits that Kahlo intended the self-portrait to “tease her ex-lover,” suggesting that in the painting the artist “is dressed ‘fit to kill’ ” with painted lips, cheeks, and fingernails, and a flower and ribbon in her hair, and jewelry pinned to her bodice.71 Her description of Kahlo’s demure, turn-of-the century, western clothing as dressing “fit to kill” clearly is based on the knowledge that Kahlo and Trotsky had an affair rather than on the visual appearance of Kahlo in the self-portrait. Yet other writers share Herrera’s interpretation, suggesting that Kahlo surreptitiously portrayed herself with the intent of captivating Trotsky’s libidinous interest. In a notable exception, Richmond describes Kahlo’s clothing as conservative but maintains that Kahlo consciously selected it because it would appear provocative to Trotsky. Richmond contends that Kahlo “is acting out a masquerade” in which she plays a “docile golden beauty” who is “settled and calm, the perfect dignified companion to a Great Man.”72 Richmond proceeds to suggest that because Kahlo portrayed herself with a “brazen carnality,” this self-portrait “is actually quite terrifying” because it demonstrates both Kahlo’s calculating ability to adopt a persona and the intrepidness with which she is “announcing that she is in control.”73 Thus, basing their opinions on Kahlo’s appearance and the dedicatory note she holds, Herrera and Richmond imply that the painting is significant in relationship to Kahlo’s private life, illustrating the theatricality with which Kahlo calculatingly adopted the very persona that would ensnare Trotsky.

Writers focusing on Kahlo’s infatuation offer contrasting accounts of her relationship. On one hand, Kahlo is described as an adoring apprentice Trotskyite, naive to the nuances of Trotskyism, but infatuated with the famous revolutionary. Richmond “suspect[s] that … she experienced a serious bout of hero worship.”74 In this case, Kahlo holds a stereotypically feminine, secondary role in relation to Trotsky. On the other hand, she is cast as dangerously manipulative and coy. Herrera claims that the painting is among Kahlo’s “most seductive self-portraits.”75 In essence, interpretations of the painting, and of the affair, construct contradictory character portraits of Kahlo; yet both fit squarely with gender stereotypes. In one instance, she submits to a subordinate relationship to the male revolutionary “authority.” In the other, as seductive mistress, she represents the dangerously coy and manipulative fallen-woman/whore persona. Interestingly, in both narratives Trotsky’s mythic status is nearly unshaken; his character largely maintained as the “great man,” the revolutionary hero.

Just as Trotsky’s sexuality has been exempt in discussions of the painting, there has been no consideration of Kahlo’s possible political sentiment. The dedicatory note begins, “For Leon Trotsky with love I dedicate this painting” and continues with a date, “the 7th of November, 1937.” The date marks the twentieth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, the essence of Trotsky’s public identity and a direct reference to his political stature. Yet because the painting exemplifies the prescribed style and subject matter of diminutive feminine art, the dedicatory note “with love” has obscured political intimations, thereby leading writers to discuss the artist’s sexual rather than political affairs. Considered in a public, political realm and in relation to the date November 7, her clothing holds political rather than sexual significance. Trotskyism generally defined itself as an international movement promoting the tenets of the Bolshevik Revolution through continuous revolution empowering the working class. Kahlo’s clothing is clearly not of a worker but of a member of the turn-of-the-century bourgeoisie, who prospered from exploitation of the working class. Thus it creates a disjuncture between herself and Trotskyism. Helland argues that Kahlo “disapproved of Trotsky’s internationalism” and only because Rivera admired him did she “befriend the exile” and invite him to stay in her childhood home.76 Thus her clothing, which was indeed a theatrical masquerade, as Richmond suggests, may be considered as politically rather than sexually significant. If the painting represents Trotskyist dedication—not by Kahlo herself, but by a fictional character constructed through Kahlo’s masquerade, who indeed attracts Trotsky politically rather than, or in addition to, sexually—it can be considered to instill critical commentary on the international movement. Accordingly, the painting mocks the fact that many supporters who “dedicated” themselves to Trotsky and Trotskyism were among the privileged bourgeois economic and social classes. Trotsky’s exile in Mexico was a bourgeois project, a political cause taken up by the “Mexican bourgeois intellectual” class, of which, Mulvey and Wollen remark, Kahlo was a member.77 The Dewey Commission, which presided over the proceedings resulting from Stalin’s charges against Trotsky, was itself an upper-middle-class, North American contingent of intellectuals. In a sense they, too, dedicated themselves to Trotsky, first by agreeing to oversee a significant international judicial proceeding and then by adjudicating in Trotsky’s favor. Yet, interpretations of Kahlo’s painting consider the politics of class, culture, and ideology to be irrelevant. Instead, she is categorically marginalized as a woman painter depicting impassioned expression.

The ambiguous setting depicted in Kahlo’s painting metaphorically represents the lack of distinction between women’s public and private social status. Kahlo is portrayed standing between drawn curtains that may be interpreted as a grand, private entrance into a domestic environment and/or a public stage which a broad audience may view. As with the juxtaposition in Henry Ford Hospital, Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Leon Trotsky) implodes the public and private. And interpretations of the painting that consider Kahlo’s association with Trotsky as purely sexual reinforce public discourses obsessed with monitoring women’s private lives and gender transgressions as a means to maintain a stable society. It is not surprising that Kahlo’s association with Trotsky has been cast as purely sexual while historical events beyond the artist’s private life have been given little attention, for a discussion of political content would be an acknowledgment that Kahlo crossed a gendered boundary by entering a masculine, political realm in addition to exhibiting aggressive sexual behavior and presuming to produce marketable works of art. Thus in addition to characterizing the nature of Kahlo’s personal feelings toward Trotsky, some interpretations of the painting exemplify how women are confined to feminine prescription, locked out of male-dominated critical, political discourse. The drawn curtains, in relation to interpretations of the painting, signify women’s sustained containment on an apolitical stage that serves to legitimate mythic masculine authority and virility. The painting’s original title was “Between the Curtains,” which, as Mulvey and Wollen assert, “gives the impression of consciously highlighting the interface of women’s art and domestic space, as though in her life (and in her dress) she was drawing attention to the impossibility of separating the two.”78 Acceding to Kahlo’s artistic success and political activism counters mythic gender dichotomy and therefore largely has been discussed separately from paintings upon which social prescription consistently is imposed.

During the late 1930s, Kahlo became an increasingly successful artist, unquestionably traversing a male-dominated domain by actively producing marketable art. Her paintings were exhibited, purchased, and commissioned. As she traveled to New York and Paris for exhibitions of her work, she interacted with well-known artists including Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamps, and André Breton. Her patrons included Edward G. Robinson, A. Conger Goodyear, and Clare Boothe Luce. The Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Louvre each purchased one of her self-portraits. But reviews of her exhibitions persistently inscribed feminine illustration as Kahlo’s primary accomplishment. For example, one review of her 1938 exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, which introduced discussion of her work with the anecdote that she had been “too shy to show her work before,” noted that “black-browed … little Frida’s pictures, had the daintiness of miniatures, … and the bloody fancy of an unsentimental child.”79 With Henry Ford Hospital and other graphic, bloody self-portraits included in the exhibition, there is an obvious discrepancy between Kahlo’s unsettling displays of the female body and the description/interpretation of the paintings. Contradictory female stereotypes are inscribed. On one hand the artist (personified by her painting style) is dainty and delicate; on the other hand she is troublesome and untamed, analogous to the child who is not yet properly socialized. Though far less blatant than 1930s reviews, that incongruity permeates interpretations published five and six decades later. For example, Herrera characterizes Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (figure 7) as a “rueful jest,” and Richmond suggests that it is a “vengeful picture” that portrays Kahlo’s “fantasy to maim her betraying husband.”80 Herrera and Richmond isolate Kahlo’s self-portrait from all social context beyond the interpersonal, arguing that the painting documents Kahlo’s emotions during her 1939 divorce from Rivera. Yet, they also insert stereotypes of the fallen woman, made even more menacing by a fury that further challenges the social balance between masculine and feminine ideals.

As Kahlo enjoyed increasing professional success, her marriage deteriorated. In 1939, when she returned to Mexico from Paris, Rivera asked for a divorce. It is difficult to determine exactly what precipitated his request. Kahlo’s brief, published comments were vague. She explained that “intimate reasons, personal causes” led to “difficulties” when she returned from Paris and New York and that she and Rivera “were not getting along well.”81 Although also enigmatic, Rivera’s comments submit that Kahlo’s celebrated success was a catalyst:

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 7. Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940. Oil on canvas, 15¾″ × 11″. © Banco de México, Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, 06059, México, D.F. 1998. Reproduction authorized by the Banco de México and by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura.

There are no sentimental, artistic, or economic questions involved. It is really in the nature of precaution. . . . I believe that with my decision I am helping Frida’s life to develop in the best possible way. She is young and beautiful. She has had much success in the most demanding art centers. She has every possibility that life can offer her, while I am already old and no longer have much to offer her. I count her among the five or six most prominent painters.82

Rivera’s description of Kahlo as a successful and prominent painter is in sharp contrast with his painted idealization of her as helpmate produced five years earlier, marking a shift in his perception of her social position, and also reflecting his social status. Although he claimed that there were no sentimental reasons for the divorce, his statement intimates his own faded virility and vitality, highly invested masculine qualities. As he describes her life “develop[ing] in the best possible way,” he labels himself “already old,” without “much to offer her.” In other words, she professionally surpassed the “great maestro,” whose commissions were in decline. Given the social contention over women’s roles, which is implied in Rivera’s statements, Kahlo’s professional success was incompatible with her role as wife. In Schaefer’s words, “As far as the art world in particular was concerned, the ‘rules’ of artistic construction separated the male professional from the intimate discreet role of the woman.”83 By the time of the divorce, public interest in Kahlo’s paintings had escalated. As she traveled to exhibition openings in New York and Paris, she metaphorically crossed a boundary from a private, feminine role to a public, masculine one. Her cultural position changed from nurturing wife to active artist, and, parallel to the paradigmatic male artist’s sexual reputation, her sexual liaisons became public knowledge. Kahlo unquestionably operated outside the parameters of idealized femininity.

Because Kahlo and Rivera were celebrities, their lives were discussed publicly. Alejandro Goméz Arias explains, “Diego and Frida lived in the middle of a forum. The publicity, whether desired or not, was inexhaustible. For Frida, there was no private life, no silence.”84 The sexual exploits of both artists were implicated in interviews that Herrera conducted with their acquaintances:

Possibly Rivera learned of Frida’s affair with Nickolas Murray. . . . Some say that the source of Rivera’s problem was sexual—Frida’s physical fragility or her lack of desire made her either unable or unwilling to satisfy Rivera’s sexual needs. Other’s say that Rivera was impotent. . . . Rivera always retained an attraction to his ex-wife [Lupe Marín], and he was tied to her as the mother of his children. . . . he might have found out about Frida’s affair with Trotsky. . . . there was a rumor that Rivera was planning to marry the pretty Hungarian painter Irene Bohus. . . . Rivera is widely believed to have been romantically involved with Paulette Goddard.85

In listing the artists’ sexual liaisons, Herrera suggests that infidelity was the most significant factor precipitating the divorce and implies that no marriage can tolerate the breakdown of bourgeois sexual mores even if both husband and wife agree to an open relationship. A distinction between “appropriate” and “inappropriate” gendered sexual behavior invades Herrera’s list. Virility is an uncontested, celebrated masculine characteristic manifested through sexual conquests. Thus rumors that Rivera was involved with Lupe Marín, Irene Bohus, and/or Paulette Goddard verify his virility. If, as Herrera notes, Kahlo was too frail or disinterested to “satisfy Rivera’s sexual needs,” then his only option for actively proving his masculinity would have been through sexual relations with other women. The intimation that he may have been attracted to Marín, “the mother of his children,” is even more ideologically significant as a fulfillment both of his masculinity and of postrevolutionary nationalism, which endorsed the family above all other intimate relations. In other words, the rumors that Herrera lists inscribe stereotypic social traits for the paradigmatic patriarchal male, implying that Kahlo did not or could not perform a feminine role to validate her husband’s masculinity; therefore Rivera ultimately requested a divorce. The reports of Kahlo’s intimate relationships are not listed in and of themselves as grounds for divorce. Rather they are enumerated in terms of whether Rivera was aware of them. “Possibly Rivera learned of” her affair with Murray or “found out about” her sexual relationship with Trotsky, thus suggesting that her active sexual pursuits and her clandestine proclivity toward masculine sexual behavior was exposed. In a strict gender binary, if the woman is actively masculine, the man by default must occupy the feminine field of passivity and submission. Almaguer argues that in Mexican/Latino culture, “only men . . . are granted sexual subjectivity.”86 Illustrating the foreclosed category of female sexuality, he cites Moraga’s autobiographical account of realizing her own sexual subjectivity: “In an effort to avoid embodying la chingada, I became the chingón. In the effort not to feel fucked, I became the fucker, even with women.”87 Thus, Almaguer explains, “In order to define herself as an autonomous sexual subject, [Moraga] embraced a butch or masculine gender persona.”88 Similarly, rumors of Kahlo’s active sexual exploits located her in a masculine realm, implicitly threatening Rivera with the possibility of residing in the feminine sphere that Kahlo had abandoned. If considered in the context of sexual gender codes, Rivera’s decision to divorce his wife exempted him from a social status construed in relation to Kahlo’s increased professional and sexual activity.