Читать книгу Hope for a Cool Pillow - Margaret Overton - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFive

Errol Morris, writer and filmmaker, wrote a five-part series on the New York Times Opinionator blog in 2010 called “The Anosognosic’s Dilemma: Something’s Wrong but You’ll Never Know What It Is.” Morris had interviewed a Cornell professor of social psychology named David Dunning who described a cognitive bias known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. To put it bluntly, it states that the incompetent are too incompetent to know how incompetent they are.vi

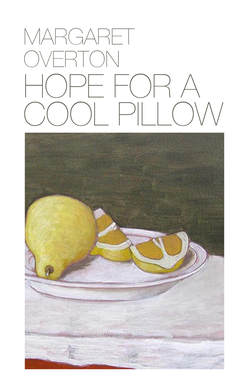

While reading the “Offbeat News” section of the 1996 World Almanac, Dunning had found the story of McArthur Wheeler, a bank robber who brazenly walked into banks, held them up, and walked out. He wore no disguise; he simply smiled into the security cameras. As it turned out, McArthur Wheeler had sprayed himself with lemon juice, which he believed would render him invisible. He had previously verified the effectiveness of the lemon juice treatment; he’d taken a Polaroid photo of himself after testing the lemon spray and it failed to show an image. Believing he was, in fact, invisible due to lemon juice, this five foot six inch, two hundred seventy pound man proceeded to rob two banks and was immediately apprehended. Lemon juice had not made him invisible to the police. Inspired by the story, Dunning designed a study to show that incompetence prevents us from recognizing our incompetence. He named his theory the Dunning-Kruger effect.

I love this story, not because it deals with incompetence, but because it proves that people have the power to convince themselves of almost anything. While incompetence is tragic, it is no more tragic than ignorance or denial. Every day, people of all levels of intelligence behave in ways that are ruinous to their health and wellbeing, physically and emotionally. And it isn’t as if they don’t know better. They usually do. But when they look in the mirror, they are awed by the power of the lemon juice.

Later in the article, Dunning remarks on those amazing words uttered by Donald Rumsfeld: “There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don't know we don't know.” Dunning states, “That’s the smartest and most modest thing I’ve heard in a year.” Though Rumsfeld specifically referred to terrorism, he might just as easily have been talking about medical care, medical research, the business of healthcare, healthcare reform, behavioral economics, or any of the fields that abut caring for our sick and healthy and the massive economic machine that entails. It’s hard to search for unknown unknowns because it feels akin to an admission of incompetency or inadequacy; as a result, it becomes a problem for intelligent people in all fields and at all levels of experience. The capable are just as at risk as the incompetent; they assume that intelligence or ability in one field naturally extends to other areas as well. They don’t know what they don’t know.

I arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts on Sunday, October 24th, 2010. Although the day was rainy, the colors of autumn would brighten in the week to come. A porter showed me to tiny quarters in the Executive Education housing building, which overlooked the Charles River. We had been divided into study groups prior to our arrival and assigned rooms accordingly. Each study group would occupy a section of housing organized around a central meeting room with a large table, a refrigerator stocked with water and soda, AV equipment, and many electrical outlets. Hallways extended in finger-like projections off the meeting rooms. My dorm room felt chilly and damp until I realized the heater had been disconnected. I removed the control panel and turned on the main switch to get some warmth going. Then I unpacked my clothes, hung everything up, and sat on the bed.

I thought of all the reading I had done to prepare for this course, the overwhelming evidence detailing the countless difficulties underlying an industry that represented seventeen percent of the United States’ gross domestic product. I thought of all the reading I had done prior to the course, in healthcare journals, in the business section of the daily paper, in articles about economics for the past two decades. Everyone seems to agree that we have troubles. But when that much money is involved, the way of thinking about problems and solutions gets constricted by the so-called politico-industrial complex. We know we want to fix the system but we don’t really want to change it all that much, especially not our part, not the part that makes us money. We’re all guilty. We want to tweak a monster just a smidge, put up a bumbershoot in a hurricane, then expect miraculous change to occur, like everything will suddenly become affordable. We don’t want it to hurt too much. So what can you do in this situation, when it seems as if everyone is wearing the lemon juice?

I guess you go to business school.

~

The first time I stuck a needle in Miriam Lewitsky, I thought she seemed ancient. She had a puffy face, straw-like hair, and bruised, fragile skin. Long-term steroids had caused those changes.

Mrs. Lewitsky was every intern’s nightmare—chronically ill, suffering, and, worst of all, the wife of a board member and therefore a VIP.

She’d been admitted three weeks earlier. Her medical attending was Dr. Cruzario, a highly regarded pulmonologist, her husband a weird but wealthy financier. She carried a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Rona, the resident, had told me on morning rounds to draw an arterial blood gas from Mrs. Lewitsky. So I gathered up the necessary equipment and headed in to meet her.

“Who are you?” she wheezed from dried, purplish lips. Her nasal oxygen cannula sat high on her forehead, sending oxygen to her hairline.

I introduced myself.

“Hullo then, young doctor.” She closed her eyes and lay her head back against the pillow. “Fix the pillows for me, would ya?”

I came around to the far side of the bed. She couldn’t lean forward on her own; I had to hold her shoulder forward with my right arm while fluffing and repositioning the pillow with my left. She wasn’t as light as she looked.

“It’s gotta be higher. I don’t like it so low.”

I pushed her forward again. The hospital gown stuck to her spine and I felt her damp skin through the thin cotton. The back of her stylish red hair was flat from the combination of lying too long in one position, infrequent washing, and accumulated hairspray.

“I suppose you’re gonna stick me for something,” she rasped. I lowered her back. She hadn’t done any work but seemed more out of breath. I put the nasal oxygen back in her nose.

“Well, actually, yes I am. We need to check a blood gas.” After nine months of internship, I’d learned to invoke the royal we whenever possible. I had no authority and little experience. Calling myself we was a semantic attempt at validation, and a surprisingly effective one.

“Don’t bother with my right wrist. It’s still sore from the last one.”

I turned her left hand over and examined the inside of the wrist. Bruises ran halfway to her elbow. I felt for the radial pulse and she flinched.

“It’s so sore,” she said.

“This is the good arm?” I asked, not feeling any pulse whatsoever.

“The other one’s worse.”

“There’s not much here,” I said. “I’m going to take a feel of the other arm. I’ll make sure to give you some local."

“A lot of good that does,” she said. She was right. The local anesthesia stung and may not have helped, but it made me feel better.

Her right wrist had a weak but detectable pulse. I set up my equipment and prepped her skin.