Читать книгу The Continual Inner Search - Margaret Winn - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

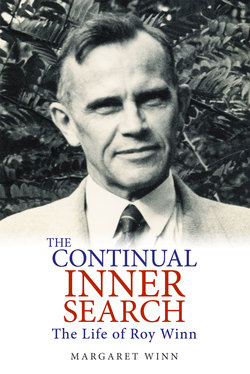

I have wanted to write about Roy Winn’s life for many years. Roy was my grandfather and very close to my father Dick, his elder son, although I did not know him well. I was only 11 when he died.

Roy was Australia’s first full-time practising psychoanalyst, a career born out of his personal experiences during the First World War. He spent a lifetime exploring the mind, trying to understand himself and others.

My father thought very highly of him, believing Roy to be an original thinker and a man of integrity who lived his own life according to his own code, seemingly unswayed by the prevailing moral climate or conventional social niceties. In Roy’s own writings, he reveals himself as witty and self-mocking, insightful and inventive. His colleagues in psychoanalysis saw him as kindly and tolerant, a man of great personal charm and fine character who had a ready smile for the foibles of human nature and acute insight into unconscious mental processes.1 He was said to have had a keen sense of humour.2

And yet I never felt entirely comfortable with Roy. I found him reserved and disengaged, uninterested in getting to know me. He did not seem to bother with idle chitchat and only spoke if he considered there was something worthwhile to say, although if you asked him a question he was pleased to answer. He was a chain-smoker, lighting a fresh cigarette from his previous one, which left him with yellow nicotine stains that, as a child, I found repellent. His wooden leg both fascinated and embarrassed me.

Nevertheless, even then, I knew him to be something special, someone to be remembered.

My mother Helen’s side of the family included many larger than life characters who were actively remembered. Helen was the grand-daughter of Sir Henry Parkes, the Father of Federation, and the daughter of Cobden Parkes, the Government Architect. Her house was full of Parkes’ heirlooms and memorabilia. She was connected to the wider Parkes clan and told Parkes’ family stories until we knew them by heart. In her sitting-room was an enormous marble bust with an imposing bosom and imperious gaze. It was of Eleanor, Sir Henry’s second wife. In the same way that Eleanor dominated that sitting room, so the Parkes family dominated the historical record of our family. We knew very little about the Winn side of my family and I liked the idea of redressing the balance.

There are many biographical details about Roy in various psychoanalytical histories and First World War books but I thought his descendants deserved a fuller picture. All those who knew Roy well – his brothers, two wives, Nanny, children and friends – are now dead, but I had videotaped interviews of my father Dick, my uncle and aunt Murray and Evelyne Winn, and their first cousin Janet Winn, and I expected that these tapes would provide a good picture of what Roy was really like and how he thought, rather than just what he did.

Despite long sessions over a number of days and notwithstanding their ability to recall specific incidents and activities, these interviews, frustratingly, provided little insight into his character, thinking or motivations. This should not have surprised me: most of the Winns I have known have tilted towards science and technology rather than the humanities, the rational rather than the emotional, the concrete rather than the speculative. Roy’s family could easily remember Winn telephone numbers and car registration plates, but could not so easily reflect on the nuances of Roy’s personality.

I turned to Roy’s two small diaries of the war and immediate post-war years, but there is not a lot to be learned from them except chronology and the scope of his activity. Roy’s Gallipoli photograph album, as well as his poems, nonsense verse and medical musings provide texture but the big hole in all the available material was in understanding his psyche. Given his work as a pioneering doctor of the mind in Australia, it was a hole I felt I needed to fill.

A handwritten document titled Men May Rise, which was found in Roy’s papers after his death, proved to be a treasure trove. It is an undated, unpublished novel written under the pseudonym John Truscott. All three of Roy’s children considered the novel to be largely autobiographical. My uncle Murray had typed copies made for family members in the late 1990s, which was fortunate, as the original manuscript has subsequently disappeared.

Besides information about Roy’s involvement in the war, Men May Rise provided insights into Roy’s thoughts and feelings about this momentous time in his life – and in world history. It tells the story of a young man, Tas Selton, who leaves Australia with the Australian Army Medical Corps and is posted to Gallipoli in 1915. The young Tas had originally intended to become a medical missionary but, as he progressed through medical school, he came to doubt his suitability for that particular calling. The novel focuses on Tas’s war service and courtship, the severe depression and jealousy that followed and his successful psychoanalytical treatment. Tas comes across as a real person and the descriptions of war have the ring of authenticity, although the supporting characters from the love story are somewhat one-dimensional and the dialogue is wooden and stilted.

Roy was no novelist but, like my father, aunt and uncle, I believe its real value lies in its realism – a faithful rendering of Roy’s own lived experience from 1915 until about 1923. This view is reinforced by the author’s note which says ‘this novel may seem rather more biographical than customary… there is no character in this book who has not, so the author hopes, a faint resemblance to some living person.’3

I suspect that Roy wrote the novel as part of a conscious therapeutic process, believing that recovery was assisted by reflecting on a traumatic experience through writing or talking about it. Given that the accounts of particular battles accurately mimic what we know of Roy’s actual war experience, one cannot help but speculate that Tas was Roy’s alter ego and that putting pen to paper likely was designed to help Roy exorcise some of his war-inflicted demons. Rather than laboriously using endless quotation marks, I have chosen to insert some of the novel’s text directly into this biography and have substituted ‘Roy’ for ‘Tas’ so that the excerpts from the novel appear as part of the narrative. I cannot be certain that every passage used in this way is an accurate record of what Roy did or what happened during this period, but it is clear that, even if it is not, it is as close to a first-hand account of the events described as one could hope. Although this decision could result in a less than fully accurate history, it is a price I decided to pay in order to flesh out Roy’s emotional state, about which we otherwise would be ignorant.

With regard to the text, Roy’s spelling is sometimes idiosyncratic. Rather than attempt to correct or highlight everything with a sic, I have generally left his words as he wrote and spelt them. Similarly, I have left measurements in acres, feet and yards as I found them.

All the photographs used in the book are from Winn archives, except the one of Winn houses on Mayfield Ridge which is from the University of Newcastle. The Gallipoli photographs were taken by Roy in 1915 and, although their quality is variable, they demonstrate the subjects that Roy found worth recording at the time.

Several generations of Winns covered in this biography anointed their descendants with a limited range of given names, such as William, Janet and Betty, and then proceeded to use them or similar names, as nicknames for other members of the clan. This practice could have caused significant confusion, so I have consistently used given names, rather than nicknames. Hence the name Bertha is used for Roy’s wife, even though he always called her ‘Betty’; and his daughter Betty is referred to as ‘Betty’, even though Roy’s pet names for her were ‘Bettina’ or ‘Bonnie’. The only exceptions are Roy’s oldest brother, William Harold Winn, who everyone referred to as ‘Harold’, his wife Ellie McMurtrie and my father Dick.

I have copies of Roy’s main professional publications and some of his medical, philosophical and poetic writings, but privacy and confidentiality concerns meant I did not have access to patient case notes or sensitive material held at the various psychoanalytical institutes. The sum of all the available material relating to Roy is scant and occasionally contradictory4 and I suspect the inevitable paucity of personal and professional biographical material will raise questions that I will never be able to answer. Still, I think it is worth doing what I can in order to present this most singular of men to his descendants.

1 Graham F Obituary of Roy Coupland Winn MJA February 1964 p333

2 Garton S Australian Dictionary of Biography ANU Vol. 12 1990

3 Winn RC Men May Rise p1

4 Official records have conflicting dates and details