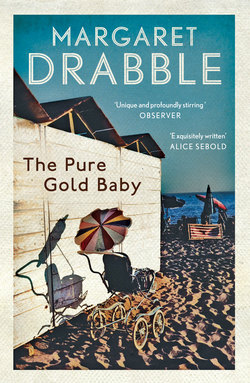

Читать книгу The Pure Gold Baby - Margaret Drabble - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWhat she felt for those children, as she was to realise some years later, was a proleptic tenderness. When she saw their little bare bodies, their proud brown belly buttons, the flies clustering round their runny noses, their big eyes, their strangely fused and forked toes, she felt a simple sympathy. Where others might have felt pity or sorrow or revulsion, she felt a kind of joy, an inexplicable joy. Was this a premonition, an inoculation against grief and love to come?

How could it have been? What logic of chronology could have made sense of such a sequence? And yet she was to come to wonder if it had been so. Something had called upon her from those little ones, and woken in her a tender spirit of response. It had lain dormant in her for several seasons, this spirit, and, when called upon, it had come to her aid. The maternal spirit had brooded on the still and distant waters of that great and shining lake and all its bird-frequented swamps and spongy islands and reed-fringed inlets, and it had entered into her when she was young and it had taken possession of her. Was this the beginning, was this the true moment of conception? Was this the distant early meeting place that had engendered the pure gold baby? There, with the little naked children, amongst the grasses and the waters?

She had never heard of the rare condition which afflicted some of the members of this poor, peaceable and unaspiring tribe, and the sight of it took her by surprise, although Guy Brighouse, her sponsor and colleague on this expedition, claimed that it had been well documented and that he had seen photographs of it. (But Guy was a hard man who would never admit to anything as vulnerable as surprise.) It was then popularly known as Lobster-Claw syndrome, a phrase which came to be considered incorrect. (It is now more widely known as ectrodactyly, or SHSF, but she did not then know that. She did not then know any of its names. The acronym SHSF discreetly encodes the words Split Hand Split Foot.) In some parts of the world, with some peoples, in some gene pools, the fingers fuse. In others, it is the toes. In this part of Central Africa, it is the toes that form a simple divided stub or stump. A small group of forebears had produced and passed on this deviance.

The little children seemed indifferent to their deformity. Their vestigial toes functioned well. The children were agile and busy on the water, and they were solemn on the land. They punted and paddled their little barks deftly, smartly They stared at the anthropologists gravely, but without much curiosity. They were self-contained. They posed on the edges of their canoes with a natural elegance, holding their spear-like poles steady in the mud. They did not speak much, either in their own language or in English, of which their elders knew some words. They were not of the tribe the team had come to study; they were a side-show incidental to the longer journey, and the team did not stay with them long or pay them close attention. They were a staging post. But in the two days that the group sojourned there, Jess (so much the junior of her team, so young that she was considered almost as a lucky mascot) observed the little children as they played a game with stones. It was one of the simplest of games, a kind of noughts and crosses, an immemorial game, a stone age stone game. Red stones, black stones, white stones, moved in a square scratched out upon the sun-hardened reddish-ochre mud. She could not follow the rules, and did not try to do so. She watched them, the simple children, playing beneath the vast African sky.

Bubbles rose from the mud of the shallow inlets, bubbles of marsh gas from a lower world. A watery shifting landscape, releasing its spirits through the green weeds. There were floating islands of tufted papyrus, a sudd that was neither water nor land. On the higher banks, the mud dried to clay. From the clay, the children had moulded toy bricks and thimble-sized beakers. They had placed them in a little circle in the rushes. A small party, awaiting small spirit guests.

The next day, on the team’s onward journey, she saw a shoebill. Their guides were pleased to have sighted this primeval bird, rare, one of its kind, primitive, powder-blue, much sought after by birdwatchers. The shoebill represents its lonely family. It has its own genus, its own species. Maybe it is allied to the pelican, but maybe not. Tourism was already making its slow way towards the lake, and the guides thought their troupe would be pleased by this sighting, and so it was. But Jess, although she liked the distinguished shoebill, was to remember the children with their simple stones and simplified toes. They were not on the tourist route.

They were her introduction to maternity. She went home, she continued her studies, but she did not forget them.

They were proleptic, but they were also prophetic. And she began to think, as time passed, that they reminded her of some early memory, a memory so early she could not recapture it. It had gone, buried, perhaps, beyond recall. It was a benign memory, benign as the children were benign, but it had gone.

She took home with her a treasure, a stone with a hole in the middle of it, a stone age stone that could make rain. It was a stone of the small BaTwa people of the lake. Had the children been of the BaTwa family? She did not know, but thought they might have been.

The BaTwa’s territory had receded and diminished. They had taken refuge not in the bush, as most displaced African tribes have done, but amongst the reeds and in the water.

Jess was to keep the rain stone with her all her life.

The pure gold baby was born in St Luke’s, a National Health hospital in Central London, an old institution now relocated in the suburbs. The building where the baby was born is now a moderately expensive hotel for foreign tourists. There is a mural in one of the public rooms evoking a medical past, with surgeons in white coats and busy nurses. Some guests think it in questionable taste. The smell of disinfectant has not been totally banished from the woodwork.

The quality of this small girl child was not at first evident. She looked, at first sight, like any newborn baby. She had five fingers on each hand, five toes on each foot. Her mother, Jess, was happy at the birth of her firstborn, despite the unusual circumstances, and loved her from the moment she saw her. She had not been sure she would do so, but she did. Her daughter proved to be one of the special babies. You know them, you have seen them. You have seen them in parks, in supermarkets, at airports. They are the happy ones, and you notice them because they are happy. They smile at strangers, when you look at them their response is to smile. They were born that way, you say, as you go thoughtfully on your way.

They smile in their pushchairs and in their buggies.

They smile even as they recover from heart surgery. They come round from the anaesthetic and smile. They smile when they are only a few weeks old, the size of a trussed chicken, and stitched up across their little breast bones with thread, like a small parcel. I saw one once, not so long ago, in the Children’s Hospital in Great Ormond Street in London. As I was introduced to her, and was listening to a description of her case and her condition, she opened her eyes and looked at me. And when she saw me, she smiled. Her first impulse, when seeing a stranger, was to smile. She was a black-haired, red-faced, wrinkled little scrap of a bundle, like a bandaged papoose, snug in her tiny crib. She had come safely through major surgery. She smiled.

I saw one of them in a long queue for check-in at an airport a year or two ago. You couldn’t miss him, or forget him. He was about eight months old, and his mother was holding him in her arms, his plump legs comfortably astride her solid hip, and he was smiling, and making free-range crowd contact, and stretching out his little waving neat-fingered hands to strangers, and responding to their clucks and waves. Other small ones in the line were grizzling and moaning and struggling and tugging and whimpering, bored and restless as they clutched their drooping toys or dragged their brightly coloured pink-and-blue Disney-ornamented plastic mini-wheelie-bags, but this one was radiant with a natural delight. His face was broad and blond and round and dimpled and shining, his hair a soft baby silken down. He entertained the long and anxious straggle of travellers. The mother looked proud and modest, as her baby was praised and admired by all. The mother was stout and plain and also round of face: an ordinary, homely young woman, the archetype of an ordinary mother, proud of her child, as such mothers are. But the baby was supernatural in his happiness.

You don’t know where they come from, or why they have the gift. Who gives it? You don’t know. We don’t know. There is no way of telling. It is from some profound and primal source, or so we may well believe. They bring it to us.

You don’t know what will happen to them in later years. Such radiance cannot last. So you say to yourself, as you watch their smiling young faces.

The pure gold baby, born in St Luke’s Hospital in Bloomsbury, was a pleasant child, no trouble to anyone. She attached herself to the nipple and fed rhythmically from the breast, she slept peacefully in her cot and breathed evenly, and her mother Jess delighted in her. She took her home to her modest second-floor flat in North London, which she rented very cheaply from a couple downstairs whom she knew from her earliest student years, and for whom she used to babysit on a regular basis. Although naturally exercised by the doubts and anxieties that beset young mothers, from the beginning she felt a love for, and confidence in, this child that took her somewhat by surprise. She had not expected motherhood to come so easily. Childbirth had been moderately painful, and was helped along with a little pethidine, but attachment came easily.

Those of you who are by nature apprehensive and suspicious will read this account as a warning, and you will be right. We worried for her, we, her friends, her generation, her fellow-mothers at the playgroup in the dusty old church hall in the quadrant. (I don’t think the word ‘cohort’ had at that time been co-opted from the dictionary for use in the sociological thesaurus.) We worried for her in the corner shop, as we bought our tins of beans and sausages, our biscuits and our boxes of eggs, our little glass jars of what we then thought of as nourishing and innocent Heinz baby food.

She was what we now call a single mother, and that was less usual then than it is now. We thought she would have a hard time, even though her baby was pure gold.

She was a single mother with an interrupted career, which she and we had assumed she would resume more actively when the child was a little older. It was the kind of career she could pursue, after a fashion, at home as well as in the field: by reading, by study, by marking papers, by editorial work on a small scholarly journal, by teaching an extramural class or two, by writing scraps of medical journalism for periodicals. (She became increasingly skilled at the last of these activities and in time was invited to write, more lucratively, for the mainstream press.) She kept in touch. She was an anthropologist by disposition and by training and by trade, and she managed to earn a modest living from these shifts and scribblings. She wrote quickly, easily, at an academic or at a popular level. She became an armchair, study-bound, library-dependent anthropologist. An urban anthropologist, though not in the modern meaning of that term.

The father of the child was never visible. We assumed Jess knew who he was and where he was, but she did not say, and nobody knew if he had been informed about the birth of this daughter. Maybe he contributed something to the child’s upkeep. But maybe he did not. Jess was not a silent or reclusive woman, and she loved to talk, but she did not talk about the man who had been, maybe still was, the man in her life. Was he a fellow-student, was he married, was he a professor, was he a foreigner who had returned to his homeland? We did not know.

We had vulgarly speculated, before the child was born, that it might be dusky. Jess had dark connections and African friends, and we knew she had once studied, if only briefly, in Africa. She knew more than most of us about Africa, which, between us, did not amount to much. But the child was fair-skinned, and her soft baby hair was light of colour.

We didn’t know enough about genes to know what, if anything, that meant.

Jess came from an industrial city in the Midlands, and had graduated from a well-regarded grammar school via a foundation course in Arabic at a new university to a degree at SOAS. SOAS! How magical those initials had been to her as a seventeen-year-old when first she heard them, and how thrilling and bewitching they were to remain to her, even into her late middle age! The School of Oriental and African Studies, situated in the heart of academic Bloomsbury. She knew nothing of Bloomsbury or of London when she arrived there, from her provincial home in white-white-white Middle England. (London in those days was full of young people from the regions who knew nothing of Bloomsbury.) SOAS was a sea of adventure, of learning, of cross-cultural currents that swept and eddied through Gordon Square and Bedford Square and Russell Square and along Great Russell Street. Jess threw herself into its waters, and swam with its tides. She loved her first year in an old-fashioned women’s hostel, she enjoyed her later bed-sitter freedom, cooking on a single gas ring and reading in bed by lamplight well into the night. Her happiness was intense. Her subject enthralled her. How had she happened upon it, so luckily? Surely, she led a charmed life. SOAS was frequented by handsome and gifted strangers from all over the world, scholars, lexicographers, chieftains, heads-of-state in waiting, and she was free to wander amongst them. It was a meeting place, if not exactly a melting pot.

At the age of twenty, walking along the ancient-and-modern thoroughfare of the Tottenham Court Road, using the august but friendly British Museum as a shortcut, sitting in timeless Russell Square on the grass in the sun, attending a seminar, listening to a lecture, shopping in shabby Marchmont Street, she was profoundly happy, her imagination filled with dreams of the future, with speculations about the lands she would visit, the journeys awaiting her, the peoples she would meet. The bomb damage of London was at last being very slowly repaired, with spirit if not always with style, and the streets of the late fifties and early sixties were full of promise and change and hope.

Some of the big men of the future were products of SOAS and the LSE and the Inner Temple. They had occupied the square mile of colonial educational advancement, and they were now in the process of rewriting history. Jomo Kenyatta, Seretse Khama, Kwame Nkrumah … the potent memory of their names hung thick in the air of Bloomsbury and Fleet Street, the big names of big beasts, the stars of the savannah, the giants who would bestride the post-colonial world. But there were also all the lesser people: the witty Indian students, the tall aspiring South African boys who had graduated from Rhodes or Cape Town, the Guyanese intellectuals, the Burmese mystics, the vegans from Mauritius, the twins from Jakarta, the would-be white middle-class dervish from Southport – all united in human endeavour, all part of the family of man. The variegation of the human species delighted Jess, and she was in love with all those peoples.

We lived in an innocent world.

What did we mean by ‘innocence’, you may ask?

When Jess was a schoolgirl in Broughborough, not many people she met had heard of SOAS or indeed of anthropology. It was chance that revealed them to her and set her on her course and her life’s long journey.

Her father, who worked in Town and Country Planning, had acquired during his travels with the RAF in the Second World War some little booklets of beautiful hand-coloured drawings of native peoples. He had been offered them in a bazaar in North Africa and, much pressed to purchase, had bought them for a modest sum. He felt sorry for the vendors in those hard times, for the boys with boxes of matches, for the old men who offered to shine his shoes, using their own spit for polish. These booklets, in their modest way, were the equivalent of the dirty postcards and obscene playing cards bought by other soldiers, sailors and airmen to while away the hours of boredom. Maybe he had purchased some of those too, but, if he did, he did not leave them lying around for his wife and his two daughters to discover. The People of Many Lands were not on display either, but neither were they hidden, and Jess came upon them in one of the little drawers in the middle of an old-fashioned fret-worked oak bureau-cum-bookcase that stood in the bay-windowed 1930s drawing room of the Speights’ home in Broughborough. They were too small to stand easily on a bookshelf. They were bound, or so she was to remember, in a kind of soft fawn kid-like leather. With the tender hide of a young goat of the Atlas Mountains.

The illustrations were a wonder to her. She found them interesting partly because of the nudity on display, so rare in those days – here were bare-breasted Africans, Papuan New Guineans with feathers, scantily clad Apaches and Cherokees, tribesmen with teeth filed to sharp points, brave naked denizens of the Tierra del Fuego. There were no visible penises, though there was a discreetly oblique view of a lavishly tattooed South American in the Mato Grosso wearing what she was later to identify as a penis sheath. But there was everything else a curious female child might wish to see. There were elongated necks, and dangling ears, and nose bones, and lip discs, and bosoms that descended like leathery sacks or wineskins below the waist, and little conical breasts that pointed cheerfully upwards.

These portraits were much more touchingly human than the photographs one could see in the National Geographic magazine at the dentist’s. Jess did not like those photographs: they seemed rude, intrusive and inauthentic. She did not like the way that the groups were lined up to grin: it reminded her of the procedure of official school photographs, always an ordeal, and menacing in its regimentation. But the artist’s work in her father’s booklets was delicate, attentive, admiring. The men and women and children were dignified, strange and independent. Maybe they were idealised: she did not at that time think to ask herself about this. She did not know what models were used. Were they drawn from life? Or copied from other books? She did not know. But she was captured as a child by the mystery and richness of human diversity.

Each figure had a page to itself, and the colours were pure and clear. The scarlet of these people’s robes and adornments was as bright as blood, the green as fresh as a leaf in May, the turquoise new minted as from the Brazilian mine, the silver and gold as delicate and as shining as the finest filigree. The skin tones were shaded in pinks and ivories and browns and chocolate-mauves and ebony. None of the extreme body shapes repelled, for all were portrayed as beautiful. They came from an early world, these strangers, from a world of undimmed and unpolluted colour, a world as clear as the colours in a paintbox, and Jess longed to meet them, she longed to meet them all.

These figures, these people from many lands, led her on eventually to SOAS, and thence to the children by the lake with lobster claws, and thence to the birth of the pure gold baby, whom she named Anna.

Jess is ageing now, but she is still, to middle-aged young Anna, a young mother.

Jess has not travelled much since Anna’s birth. She has left the field. As a student, she had pictured herself eagerly wandering the wide world. But she has been constrained by circumstance, like many women through the ages, constrained largely to an indoor terrain. Her daughter must come first, and for Jess maternity has no prospect of an ending.

As an anthropologist, Jess is sensitive about public perceptions of her calling. Certain academic and intellectual disciplines, certain professional occupations, seem to be fair game for dismissive mirth: sociologists, social workers, psychoanalysts – all receive a share of public mockery and opprobrium, along with, for a different class of reasons, estate agents, dentists, politicians, bankers and what we have recently come to call financial advisers. When Jess was a student and a beginner, it did not occur to her that there was anything comic about her interests, and it came as a shock to her to discover later in life that anthropology was associated in the vulgar mind with prurience and pornography and penises. She was educated in what she believed to be a noble tradition. Flippant jokes about the sexual antics of savages were as irrelevant and incomprehensible to her as the double-entendres in the pantomimes she was taken to see in Derby as a small child. She could not see anything innately funny about the Trobriand islanders, or in young people coming of age in Samoa. Interest, yes; comedy, no.

In her sixties, she was to become interested in popular conceptions of anthropology and in its use as a motif in fiction. She wrote a paper on the subject which you may have read. In fiction, she claimed that it was usually exploited by flip and smart intellectuals: Cyril Connolly, William Boyd, Hari Kunzru – writers to whom it seemed to invite parody. Margaret Mead herself was the butt of endless reductive and sexist jokes. Saul Bellow, in Jess’s view, offered an honourable exception to the tradition of anthropology-mockery, and his novel Henderson the Rain King, which she had read at an impressionable age, had a profound influence on her. It summoned up to her the mystery of the dignity of the tribe of the lobster-claw children, although they do not, of course, feature in Bellow’s novel, or, as far as she knows, in any novel. Bellow, she believes, knew even less of the physical continent of Africa than she, but he wrote about it well, and he would not have made fun of lobster feet.

Towards the end of Lolita, arch-parodist Vladimir Nabokov produces a classic example of anthropology-mockery, admittedly put into the mouth of a sexual pervert pleading for his life at gunpoint, but nevertheless a vulgar and sexist passage, for all that: the novel’s pervert-villain-victim, bleating drop that gun as a refrain, tries to buy off anti-hero Humbert Humbert’s vengeance with increasingly desperate offers, including access to his ‘unique collection of erotica’, which includes the folio de-luxe edition of Bagration Island by the explorer and psychoanalyst Melanie Weiss, ‘with photographs of eight hundred and something male organs she examined and measured in 1932 on Bagration, in the Barda Sea, very illuminating graphs, plotted with love under pleasant skies’. Jess was horrified by a late rereading of this classic novel. She had disliked it in her twenties, when she was too young and innocent to understand it, but in her sixties she understood it and she was appalled by it.

You may assume from that that Jess was by nature prudish, but we didn’t think she was.

There are penises and penis-enhancement remedies advertised all over the internet now, where you might expect to find them, and Jess has written a paper on them too, in which she wittily analyses the bizarre vocabulary of commercial erections and sperm volume: the lingo of the solid high-performance-dick-enlarged-joystick-loveknob-supersized-shlong-cockrock. Jess has made a decision to find this sales patter entertaining rather than offensive, and to admire the ingenuity with which salesmen repeatedly penetrate her battered spam filter. She has even decided, paradoxically, to detect a male respect for the female orgasm in all the sales talk. Decency is an artefact, and has failed to save our culture or centre our sexuality, so maybe, she speculates, an overflowing flood of what used to be called obscenity will. Battered and drenched by massive earth-shattering orgasms, we will all be purified.

Initially, she had been rereading Lolita in search of representations of unqualified and obsessive and exclusive love, which she refound there too, as she had dimly remembered them – but tarnished, perverted, tarnished. There is genius, but there is coldness. Jess’s heart cannot afford to give space to coldness. She cannot afford to allow herself to cool and freeze.

Jess has given the large part of her life to exclusive and unconditional and necessary love. That is her story, which I have presumptuously taken it upon myself to attempt to tell. But her love takes a socially more acceptable form than that of Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert, the tragic lover of a nymphet. Jess has had her less reputable adventures, but she has so far remained true to her maternal calling through all vicissitudes.

I have taken it upon myself to tell this story, but it is her story, not mine, and I am ashamed of my temerity.

The playgroup and corner-shop mothers did not notice what was wrong with Anna for a long time, not for many months. Nor did Jim and Katie downstairs, although they saw more of her, and babysat for her reciprocally when Jess wanted to go out for an evening to have supper with friends. And as regularly as they could, they would look after Anna on Jess’s working Thursdays. We all saw Anna as a pretty, friendly, good-natured, smiling little thing, with a touching spirit of sharing and helpfulness. At an age when most small children become violently possessive and acquisitive she was always ready to hand over her toys or share her Dolly Mixtures. She did not seem to resent being pushed or tumbled, and she hardly ever cried. She laughed a lot, and sang along with the jingles and nursery rhymes; she knew a lot of the words of a lot of the verses. She had a special friend, a small mischievous imp boy called Ollie, with gap teeth and corkscrew ringlets, who exploited her generosity and used her as a decoy. Ollie seemed fond of her, even though he stole the best bits of her packed lunch. (He had a yearning for those triangular foil-wrapped portions of processed cheese, regularly supplied by Jess, which Anna would trustingly offer in exchange for a crust or a broken piece of biscuit.) The two downstairs children also made a pet of her, and played hide-and-seek and run-around-the-house and den-under-the-table with her.

So it came as a shock to be told that she had problems.

She was, it is fair to say, a little uncoordinated, and was often clumsy. Sometimes she dropped things or knocked things over or spilt her juice. But what child does not? Her speech, perhaps, was a little simple, with a tendency towards a repetition of phrases, sometimes meaningless, that appealed to her. She never learnt to manage the dumpy little thick-wheeled red-and-yellow tricycle that the playgroup provided: she could not get the hang of pedalling. But she could walk, and she could speak, and she could play simple games, and assemble structures of wooden bricks and basic plastic parts, and draw patterns with crayons. She particularly liked water play, and was very happy when allowed to splash and scoop and fill little cans and beakers and sprinklers from the inflatable rubber pond in the yard. She fitted in, and was accepted by her peers. At eighteen months, at two years, even at three, her cognitive and developmental problems were not obvious, for her goodwill and eagerness to participate disguised and overcame her lack of skills. She never appeared frustrated by her failures, or angry with herself or others. She was no trouble to anyone. We all liked her. Nobody noticed how different she was.

Except her mother. Jess, of course, noticed. She checked Anna’s progress against the progress of the children of her friends, and saw that in comparison she was slow. For a while she kept her worries to herself, hoping that Anna was simply (whatever simply, in this context, might mean) a late developer. The Health Visitor and the nurses at the surgery and the doctor who administered vaccinations did not at first seem unduly anxious, charmed, as were we all, by the infant’s good looks and beguiling demeanour. Over those first years, we entered into a conspiracy of silence. Who wants to give bad news, who wishes to insist on hearing bad news? There are many subjects of which it is better not to speak, of which it is unwise to speak. The child was healthy enough. She ate well, she slept well, she was peaceable in all her ways. Would that all children were as well loved, as well clothed, as well cared for, as well disposed as she.

It was on a cold day in February that Jessica Speight set off, unobserved, with her daughter Anna, for the doctor’s morning surgery in Stirling New Park, the long, wide, late-Victorian residential street that curved between and linked the two main bus routes into town. She dressed her warmly, in her little red fleece-lined waterproof jacket, her black-and-white-striped bobble hat, her well-washed matted black woolly tights, her mittens on a string, her little black boots, and she strapped her into the pushchair, and set off towards her appointment with enlightenment. There had been snow, and a few thin grimy frozen traces of it lingered still in hedge bottoms and gutters, lace-edged, like frozen dirty clusters of elderflower, stained yellow by dog urine, scuffed by tyres and shoes.

On such a day, one sets forth bravely, or not at all.

Anna was content, as always, and pointed with her woollen fist at objects of interest on the route. A bicycle, a red car, an old man with a peeling plastic tartan shopping bag on wheels. She let out from time to time little cries of surprise, of approval. Jess, as she walked, thought of the child’s father, and of her extreme reluctance to share her full knowledge of Anna with him. She thought of the corner ahead around which happy mother and happy child were about to disappear for ever.

She thought also of her own father, to whom she had told some of the complicated story of her affair with Anna’s father, and of her unexpected pregnancy. (She had not yet disclosed to him her anxieties about Anna, fearing that to articulate them would be to confirm them.) Her father, a tolerant, affectionate and kind-hearted man, had listened with sympathy and interest to this tale, and had condoned and indeed approved her conduct. She had done the right thing. The circumstances were indeed unfortunate, but she had chosen the right path, and he would always stand by her. He respected her independence, but if in need, she could always turn to him. Her mother’s response had been more anxious and equivocal, but she too had refrained from overt criticism and condemnation.

If Anna’s condition was as compromised as Jess now feared, she would be able to tell her own father about it, if not Anna’s father. He would understand. That was a comfort.

Jess, as she walked, found herself thinking of her father’s response to this London neighbourhood in which she was now living. He had visited it only briefly, on a couple of occasions, and had admitted that he was bewildered by its resolute shabbiness, its many-layered decay, its strange population of indigenous old Londoners, incomers from the West Indies and Cyprus and Turkey, and young married couples with professional aspirations. He had gazed quizzically at the cheap Chinese take-aways, the old-fashioned Co-ops and rustic-picture-tiled Edwardian dairies, the cobbled alleys, the junk shops full of worthless Victoriana, the make-shift garages and lean-tos, the dumped cars, the small council blocks, the large old multi-occupancy houses belonging to absentee landlords. He took in the dogs and sparrows and starlings. He liked, or he said he liked, the little jerry-built cosy Edwardian terrace where Jim and Katie and Jess lived, but Jess could tell that he found the surroundings depressing. It was not for this that he had fought in North Africa, and tried to rebuild a brave new Broughborough.

Philip Speight was a disappointed man of strong opinions, who had held high hopes for post-war Labour Britain, for the new cities that would rise from the bomb sites. His visions had been frustrated, his plans sabotaged, and his name had become attached to some of what he considered the ugliest rebuilding in Europe. Corners had been cut, money both saved and wasted, councillors had grown rich, and he had been blamed for decisions not freely of his making. The Midlands had become the badlands, and were a mess, by which he felt himself condemned. His name would go down on the wrong side of progress. The ugliness of the new weighed on him, he told Jess. The failure of Modernism depressed him.

But he was a good man, a generous man. He did not allow his depression and disappointment to infect others. He contained them.

Jess had tried to reassure him that she was happy in this cheap rundown muddle of a once-more prosperous district, but now, as she walked along in her cheap smart sixties boots, wheeling and bumping her innocent charge along the uneven pavement, her courage faltered. Maybe it was all too much for her, her fate too hard to handle.

She dreaded what the doctor would tell her.

When we look back, we simplify, we forget the sloughs and doubts and backward motions, and see only the shining curve of the story we told ourselves in order to keep ourselves alive and hopeful, that bright curve that led us on to the future. The radiant way. But Jess, that cold morning, was near despair. She did not tell us about this then, but of course it must have been so. I picture her now, walking along the patched and pockmarked London pavement, with its manhole covers and broken paving stones, its runic symbols of water and electricity and gas, its thunderbolts and fag ends and sweet wrappings and spatters of chewed and hardened gum, and I know that she faltered.

There were fag ends everywhere. Most of us smoked in those days. We knew better – we had the warnings – but we didn’t believe them. We didn’t think the warnings were for us. We didn’t chew gum, we’d been brought up not to chew gum, but we smoked, and, almost as soon as it became available, we took the pill.

The doctor, middle-aged, grey-haired, round-shouldered, cardiganed, not the best of doctors, but kind-hearted and good-enough, listened to Jess’s story, took notes, asked questions about the baby’s delivery. Had it been prolonged, had forceps been used, had there been oxygen deficiency? She did some simple tests, asked Anna a few simple questions, then busied herself writing referrals to specialists and hospitals. It occurred to Jess that this doctor, who had seen Anna several times on routine occasions (vaccinations, a bout of acute ear ache, a scraped knee that might have needed a stitch), might feel remiss for not having noticed Anna’s developmental problems. Jess, in her place, would have felt remiss. Certainly the solemnity and the new and marked attentiveness of the doctor’s response were not reassuring. There was no suggestion, now, that Anna would be a normal child. She would be what she would be – a millstone, an everlasting burden, a pure gold baby, a precious cargo to carry all the slow way through life to its distant and as yet unimaginable bourne on the shores of the shining lake.

Jess wept as she walked home, for the long-term implications of this visit, although as yet imprecise and unconfirmed, were very present to her. She was ashamed of the warm tears that rose in her eyes and spilled down her cold cheeks, of the water that dripped from her reddened nose. She wiped her face with the back of her woollen glove. Why should she weep? Her snivelling was treachery. She was weeping out of self-pity, not love. Anna smiled still, as gay as ever, wheeling royally along in her battered little second-hand pushchair. There was no difference for her, to her. There would never be any difference to her. For as long as Anna lived, provided good-enough care were taken, there would probably be no difference, thought Jess, vowed Jess.

How long would she live? Who would outlive whom?

This was also a question, and one that would become more urgent with the years. But it was far too soon to ask it yet.

It would always be too soon. The moment to ask this question would never come.

Jess decided that she would be better than good-enough. She would be the best of mothers. So she resolved, as she increased her speed and made her brisk, cold way home to a lunch of boiled egg and Marmite-and-butter toast, Anna’s healthy favourite.

We didn’t know about cholesterol then. It hadn’t been invented.

I don’t know which of us was the first to receive Jess’s confidence about Anna’s condition. Probably it was Katie, but it could have been Maroussia, or it could have been me. We were all good friends, good neighbourhood friends, with children of much the same age. I wouldn’t claim I had a particularly close relationship with Jess, in those early days, but it has endured for so long that maybe it has become particular with time.

We didn’t know whether the child’s father knew anything about Anna at all. We weren’t sure who the child’s father was. Some of us gossiped about this, I am sorry to say, but we didn’t really know anything definite. We gossiped, but we weren’t nosy. We were well intentioned. And we didn’t gossip as much as you might think. There was something about Jess, some confidently brave aura, that repelled impertinent speculation.

This is how it was. This is the version that we came to believe.

Jess, it was eventually disclosed, used to spend her Thursday afternoons with Anna’s father in a small cheap hotel in Bloomsbury, making love. The regularity of this date did not detract from its vigour and its intensity. Anna’s father was, of course, a married man, who had no intention of leaving his professor wife. He too was a professor, he was Jess’s professor, whose lectures at SOAS she had attended.

It is strange that Jess did not resent the structure of her relationship with the two professors, but it is a fact that she did not, or not very much. She accepted it, just as she had accepted the advances of her 44-year-old lover when he had propositioned her in a corridor, and led her into his study, and locked the door, and laid her upon the institutional professorial Turkey carpet.

She not only accepted them, she welcomed them. She found him very attractive. Well, perhaps that is an understatement. She thought herself ‘madly in love’ with him, though in later years she came to see that this phrase (which she employed only in the schoolgirl privacy of her student mind) was merely a gloss on her finding him ‘very attractive’. Love excused and gave permission to adulterous sex, but really it was sexual desire and straightforward bodily lust that possessed her every Thursday afternoon in the modestly functional Marchmont Hotel. Desire was satisfied unfailingly, and that, at this stage in her life, was quite good-enough for Jess. Not many women get that much. She knew that, from the stories of her friends, from the New Wave women’s magazines, and from reading the new novels of the day, which were beginning to pay close if belated attention to the female orgasm.

Jess and the Professor had no problems with orgasm.

The arrangement they came to was, for its time and place, unorthodox, but, as anthropologists, they were familiar with the immense variety of human arrangements, and not inclined to pass temporal judgement upon them. In this, they were ahead of their time, or out of their time. It doesn’t matter which. Or it would not have mattered, had there not been consequences, in the form of Anna.

It could have been Katie who was first to know about Anna, it could have been Maroussia, it could have been me, or it could have been the blond egocentric sexually athletic Professor Lindahl (a specialist, as it happened, in Chinese agrarian societies). A few months after the initial diagnosis, we all knew, and had progressed beyond the stage where we made comforting remarks like ‘I’m sure she’ll catch up soon’ or ‘She seems perfectly normal to me, my Tim (or Tom, or Polly, or Stuart, or Josh, or Ollie, or Nick, or Ben, or Jane, or Chloe) can’t do up his shoelaces/ write her name/ ride a bike/ count beyond twenty.’ Those were the days of tolerant, progressive, permissive parenting, when it was not the fashion to impose great expectations or much discipline upon one’s offspring. The prevailing philosophy was of laissez-faire, and we believed in the noble savage, the blank slate. Original Sin had been banished, and we held that, if nurtured by kindness, natural goodness would always prevail. Our chief pedagogue Dr Spock told us that babies usually knew best, and that mothers should trust them, even if they wanted to live on a diet of beetroot or burnt toast.

Motherhood was being deprofessionalised, but not deskilled. Trained nannies were out of fashion, because they were too expensive for the new generation of struggling working mothers. Trained nannies were for unemployed rich mothers, in those days. Improvisation was in favour with the middle classes: au pair girls, amateur and cheap nursery groups, reciprocal child-minding.

This was lucky for Anna and her mother.

It is not surprising that Jess and some of her closer friends began to be deeply interested in the subject of birth defects, childhood illnesses and inherited abnormalities, despite their faith in the natural goodness of infants, and despite Jess’s necessary assumption that Anna’s paternity had nothing to do with her condition. This was a period when important discoveries were being made about the chromosomal basis of Down’s syndrome (not that Anna was thought to have Down’s syndrome), and certain inherited genetic diseases were being routinely tested for at birth, not always with the mother’s knowledge or consent. (It was at this time that Jess’s mind began to go back again and again, involuntarily, almost dreamily, not unhappily, to those little agile club-foot children by the shining lake.) Vaccination was then, in the sixties, a major ethical issue, though autism, with which it was later to be (as we now think erroneously) connected, was not as yet a frequent or popular diagnosis.

Autism is now, in the twenty-first century, a hot topic. Down’s syndrome is not. You can’t make much of a career from studying Down’s syndrome. It doesn’t get you anywhere. It’s low key and unsensational. You can maintain, you can provide care, you can campaign to alter attitudes and perceptions, you can argue about the ethics of termination. You can admire Lionel Penrose for his research on the chromosome at Colchester, for his enlightening discoveries and enlightened Quaker principles, for his respectful attention to, and affection for, his patients.

You can respect. You can abort. You cannot cure.

Most of us were amateurs, struggling on with motherhood and learning as we went, but Sylvie had studied medicine and qualified as a general practitioner before her marriage to the dashing and increasingly absent Rick Raven, so we used to listen to her as our neighbourhood expert on medical matters. She wasn’t practising at this time, when her boys were small, but she would take up her career again later, and specialise in the urinary tract. We didn’t know then that she was going to do that, and neither did she.

To vaccinate, or not to vaccinate? This was hotly debated by a new generation of highly educated mothers who wished to apply intelligence as well as instinct to maternity. It was a divisive topic. Sylvie Raven was in favour, but some of us were not. To maim one’s healthy child while aiming to protect it seemed a tragic choice, and yet we knew such things could and did happen. It was for the good of the wider community to vaccinate (and of course we all thought we had social consciences), but how would the wider community help two-year-old Andrew Barker, brain-damaged by a jab that went wrong? He had gone into spasm, his back had arched, he had cried out, and he had never been the same small happy child again. This was a worse fate than Anna’s, Jess had to believe, and the sense of guilt endured by his mother was, although unfairly, greater.

Even Sylvie Raven conceded that.

We were surprised and a little shocked when Michael and Naomi decided to have their son Benjamin circumcised, and to have the job done by an unhygienic old rabbi in the living room, not by a doctor in a hospital. This too seemed to us like a gratuitous assault on the body of an infant.

We’d never even heard of female circumcision then.

We didn’t know much about genetics, but we did know that abnormalities ran in families. Ollie’s little sister had an extra digit on her right hand, an oddity which didn’t seem to worry her or her parents very much, though they did eventually arrange for its surgical removal at Great Ormond Street Hospital. They said that at first she missed her little extra thumb, but then she forgot about it, unless reminded. Her grandmother had had the same anomaly One, two, three, four, five, once I caught a fish alive … most counting games work on a five-finger base. It’s not a good idea to have six fingers.

None of us took thalidomide, but we knew mothers who had. It was one of the pharmaceutical discoveries of our time.

This was the last generation of British children to suffer routinely from such common complaints as measles and whooping cough. Diphtheria was on the wane, and so was scarlet fever, now so rare that when one of the children at our nursery group contracted it the doctor did not recognise it, never having seen a case. It was diagnosed, correctly, by the elderly untrained minder of the neighbourhood, Mrs Dove, who did the Monday and Wednesday shifts at the playgroup wearing an old-fashioned flowery cotton overall. It was greeted with delight by the medical students at the Royal Free Hospital as a lucky sighting, a historic anomaly The students made a great fuss of hot and prickly little Joe, with his red skin and his impressive fever of 105 degrees: he was a throwback to another age, and his bright blood, rocking in its tray of little test tubes, was a miracle of liquefaction.

Anna’s condition did not seem to answer with any precision to any known descriptions. Like the shoebill, she was of her own kind, allotted her own genus and species. She did not suffer from any metabolic disorder, of either rare or frequent incidence. Brain damage in the womb or at birth was not ruled out, but could not be confirmed: Jess’s labour had been long, but not unduly long, and the period of gestation apparently normal. (There were, of course, no ante-natal foetal scans in those days, no anxious calls for the dubious risks and safeguards of amniocentesis.) An obvious genetic cause was sought in vain. It is not known if or at what stage Jess proffered the identity of the Professor to the assessors, but, as far as she knew, there was nothing in his family background to suggest that a clue lay in that remote nomadic Nordic hinterland.

Jess’s attitude towards the Professor and his paternal obligations was extreme and bizarre. She wished to disconnect him from the story, and she appeared to succeed in doing so. It is more often men that wish to disconnect sex from procreation. Jess was a female pioneer in this field, although maybe she did not regard herself in that light.

It was easier to ignore the consideration of paternal genes then than it would be now. We did not then consider ourselves held in the genetic trap. We thought each infant was born pure and new and holy: a gold baby, a luminous lamb. We did not know that certain forms of breast cancer were programmed and almost ineluctable, and we would not have believed you if you had told us that in our lifetime young women would be subjecting themselves to preventative mastectomies. This would have seemed to us a horrifying misapplication of medical insight, but we would of course have been wrong. We had heard of Huntington’s chorea (‘chorea’ isn’t a word you can use now) and cystic fibrosis, but we thought of them as rare and deviant afflictions. Most genes, we thought, were normal. We did not believe in biological destiny. We thought we and our children were born free.

You may pity us for our ignorance, or envy us for our faith.

So Jess did not closely pursue genealogical explanations for Anna’s state. Her investigations were desultory. In her own heritage she traced a distant case of cerebral palsy, a couple of suicides and, at the beginning of the twentieth century, a child with Down’s syndrome (then called Mongolism, a term, like lobster claw and chorea, now obsolete). The condition of this child was easily explained by the advanced age of his mother at conception, a factor discovered by Jess on one of her covert visits to Somerset House. (The story of the Down’s syndrome boy had been handed on through family lore, through the paternal line in Lincolnshire, and reinterpreted by Jess: Jack Speight had been ‘a bit simple’, ‘a backward boy’, a young man ‘who couldn’t do much for himself’, and he had died in his thirties.) Anna’s condition did show some behavioural affinity with that of many Down’s syndrome children – an innate happiness of temperament, an at times overtrusting nature, a love of singing, a lack of the finer motor skills. But of chromosomal evidence for the condition there was none.

Anna as a child and as a young person was not identifiable, visually, as in any way impaired. Her learning difficulties were not obvious to the eye. This was both a blessing and a curse. No leeway was given her, no tolerance extended to her by strangers. Jess, who quickly became expert in spotting the cognitive and behavioural problems of other young people, found this at times a difficulty. Should she smooth Anna’s way by excuses, or allow her to make her own way through the thicket of harsh judgements and impatient jostlings that lay before her through her life? She tried to stand back, to let Anna make her own forays, her own mistakes, but occasionally she felt compelled to intervene and explain.

Anna loved her mother with an exemplary filial devotion, seeming to be aware from the earliest age of her own unusual dependence. As our children and the other children we knew came to defy us and to tug at our apron strings and to yearn for separation, Anna remained intimate with her mother, shadowing her closely, responding to every movement of her body and mind, approving her every act. Necessity was clothed with a friendly and benign garment, brightly patterned, soft to the touch, a nursery fabric that did not age with the years.

In those first years, before the educational attainments of her peers began to demonstrate a noticeable discrepancy, Anna remained part of a ragged informal community of children which accepted her for what she was, prompted by the kind example of their parents. The parents admired Jess for several good reasons, and they liked little Anna, so smiling, so unthreatening in every way, so uncompetitive. Ollie, Nick, Harry, Chloe, Ben, Polly, Becky, Flora, Stuart, Josh, Jake, Ike, Tim and Tom tolerated Anna easily, willingly. They indulged her and let her join their games, according to her ability.

But the games grew more complex, and Anna was left behind.

Anna could not understand why she could not learn to read, as the other children did. What was this game called ‘reading’? Picture books and stories she loved, particularly repetitive stories and nursery rhymes with refrains, which she could memorise word for word, and repeat back, expressively, and with a fine grasp of content, to her mentors. ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’, ‘Polly, Put the Kettle On’, ‘Curly Locks’ and ‘Incey Wincey Spider’ were part of her considerable repertoire. But letters remained a mystery. She learnt to draw A for Anna, but produced it in a wobbly and uneven hand, and was slow to get to grips with n.

Jess noticed that although Anna could sing her way through ‘One Two Buckle My Shoe’, ‘One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Once I Caught a Fish Alive’ and other counting rhymes, she could not count well without the aid of the rhyme. She needed the mnemonic. She found numbers on their own confusing. She would never, Jess suspected, Jess knew, become wholly numerate.

Jess and I didn’t talk much in those early days about Anna’s condition, but of course I was well aware of it, as were we all. A kind of delicacy prevented me from asking direct questions, and I waited for whatever Jess wished to divulge. My children – but this story isn’t about my children, I haven’t the right to tell their stories – my children were friendly with Anna, and she spent quite a lot of time with me and my two boys. I was working part time then, and Jess and I looked after one another, covered one another. My boys had known Anna since she was born (one is two years older, one more or less exactly the same age), and for years they didn’t really notice there was anything different about her. And as they began to notice, so they gradually began to adjust their interactions with her, looking out for her when there were games she couldn’t manage, taking extra care crossing the road. They used to take her to the corner shop with them on Saturday mornings to spend their weekly pocket money in a binge on Refreshers and Spangles and Crunchy Bars and Smarties. They negotiated with the temperamental grey-faced heavy-smoking old man who kept the till, and made sure she got back the right change. I didn’t have to tell them to do this. They knew.

Maybe we shouldn’t have let such little ones go along the road and over the zebra crossing together, but we did. They all learnt their Green Cross Code, but I think they used to go to Mr Moran’s even before the Green Cross Code was invented.

They weren’t saints, my children, they weren’t angels, they weren’t always patient, and I remember one horrible afternoon when Ike lost his temper with Anna. It was teatime in our house, and she managed to break a limb off his little wooden puppet man. Ike was very attached to that little puppet man, whom he called Helsinki, and he’d sometimes let Anna play with him and twist him about, but that day she screwed his arm one notch too far in an attempt to make him wave, and it came off. Ike was very cross, and called her a clumsy stupid silly girl, and snatched Helsinki back and said she could never ever touch Helsinki again. Anna’s eyes grew large with tears, and she retreated behind the enormous mahogany veneer radiogram in the corner. I intervened and said I was sure I could fix Helsinki with a dab of Superglue and I put on a record to distract them (I think it was ‘Nellie the Elephant’) and opened another packet of chocolate fingers, but Anna wouldn’t come out from the corner for quite a long time.

When Jess came to collect her, Anna was still quite subdued, and I felt miserably guilty. I didn’t know whether to explain what had happened or not. I didn’t want to betray Ike, who was such a good lad on the whole. So it wasn’t all easy, all the time. There were moments. And I never did manage to fix Helsinki properly. I couldn’t get the joint to articulate. He had a stiff arm for the rest of his short wooden life.

But Anna and Ike got over this incident, and forgave one another. Neither bore a grudge.

Ike’s name wasn’t really Ike: it was Ian, but Jake called him Ike when he was a baby, by analogy with his own name, and it stuck. He still calls himself Ike.

Jake and Ike, my babies.

Sometimes Jess and I would have a glass of wine, after these teatime child-minding sessions, and talk about grown-up matters. I would report on ethical dilemmas in the charity where I worked, or spill Whitehall secrets from my husband’s ascendant career at the Home Office, and she would tell me about whatever she was reading or reviewing, and about the thesis on which she was working. I learnt a lot of second-hand anthropology from Jess. She aired her ideas on me. I liked to hear her talk about the shining lake, the children and the shoebill, and about Dr Livingstone, whose grave she said she had visited. We were both mildly obsessed by Livingstone, then a deeply unfashionable and intellectually provocative figure. She knew far more about him than I did, but I had missionaries in my family background, and old missionary books on the family bookshelves, and as a child I had browsed through my great-grandfather’s school prize of Livingstone’s Travels, with its thrilling engravings of ‘The Missionary’s Escape from the Lion’ and ‘Natives Spearing an Elephant and Her Calf’. I was always interested in reports about Livingstone. We speculated about what he had really, truly believed.

Jess and I talked a lot. We talked about everything.

When the children got tired they would watch Blue Peter, or whatever came on after Blue Peter. Ike used to suck his thumb when he watched telly. I’m sorry to say I used to like to see him suck his thumb. It was strangely comforting. And he did grow out of it.

Children’s television seemed very wholesome and educational in those days, although now we’re told it wasn’t all it seemed.

Playgroup and nursery group were easy enough for Anna, surrounded by neighbourhood friends. Jess worried that when she went to primary school she would be exposed to potentially hostile strangers, even though she would still be in the company of Tim and Tom and Polly and Ollie and Ike. Jake and Stuart, two years older, had already gone ahead to defend her in the playground and taught her the ropes. And Anna’s skills sufficed in the first year of Plimsoll Road Primary, with the other five-year-olds and six-year-olds, under the benevolent and knowing eye of pretty, long-legged, mini-skirted Miss Laidman. Miss Laidman, who had studied pedagogy at an avant-garde teachers’ training college in Bristol, was well aware of Anna’s difficulties, and became expert at including her in group activities. Anna and Jess were lucky in Miss Laidman, and the school itself had a benevolent regime. Jess was grateful for this, but knew that such luck and such participation with her tolerant peers could not last for long. The next stage must come soon.

It was considered by the professionals and indeed by Jess that Anna would, in time, be unable to cope with the demands of state primary education. A special school of some description would have to be found, where she could acquire special skills. In the right environment, she might even be able to learn to read. Miss Laidman encouraged Anna to write her letters, but she could not teach her to read.

Miss Laidman had a colleague called Fanny Foy, who taught music at Plimsoll Road and at one or two other schools in Stoke Newington and Finsbury Park. Miss Foy loved Anna, and would spend extra time with her. Miss Foy had a little sister like Anna. Fanny Foy, I discovered, moonlighted and played the violin in a theatre orchestra at night. She had a double life. She knew all the musicals. She taught Anna the tunes and a lot of the words.

When Anna was seven, Jess moved out of the upstairs flat above Jim and Katie, feeling perhaps that she should not become too attached to, or dependent on, them or their residence. Or perhaps she was getting irritated by the competitive marital discord occasionally displayed in the household. Jim and Katie were relieved, though they did not say so, because they needed the extra space for their own growing family: when Jess announced that she was moving, Katie had a third child on the way. They needed the space and, prospering on two incomes, they no longer needed the rent. And probably they were not happy with a witness to their domestic discord. Better to rage in private than in earshot of a highly acute and perceptive lodger and her innocent and perhaps too guileless child. Jim’s ambitions and Katie’s ambitions were increasingly in conflict, and the conflict was becoming increasingly overt.

Jess moved to a shabby little three-storey terraced property a few streets away, in easy reach of her old friends and our reliable support system. Houses were cheap then, and, although it was difficult for a single woman to get a mortgage, Jess must have produced a satisfactory deposit for No. 23 Kinderley Road N5, raised from her father, or from the Professor, or from some other undisclosed source of finance. She must have found a friendly broker. She was, after all, a graduate in what was considered respectable and regular, though not very remunerative, professional employment. Maybe the Professor gave her a good reference. He could hardly, one might think, do less: although really, when considering the Professor, it is hard to know what to think that he might have done.

Sometimes I wondered if Jess made up the story of the Professor. She told it to us in instalments, over those early years, and perhaps improved and embellished it at each telling. We are all adept at rewriting the past, at reinventing it. Perhaps Anna was the result of a one-night stand, or of a liaison with a fellow-student of which Jess was ashamed, and which she had decided to disown.

The story of the Professor was, as Jess unfolded and disclosed it to us, dramatic and colourful. It had those virtues. Jess was a good storyteller. She has told me many stories, over the many years of our friendship, and some of them have certainly altered in the telling. Some of them have become so entangled with my own memories that I feel as though I have witnessed events that are part of her life, not mine. This is partly, but not wholly, to do with Anna’s love of repetition. Anna would say, ‘Tell us about that time when Gramps tried to jug the hare’, or ‘Tell us about when you went swimming in your nightie’, or ‘Tell us about the tree-frog’, or ‘Tell us about when Gramps ate the mouse’, and Jess would tell.

Jess is a good listener as well as a good narrator. I have told her things I have never told to anyone, should never have told to anyone. Jess was, and is, an attractive woman, with a hypnotic intensity of attention that tends to mesmerise an interlocutor. She concentrates on others in a manner that sucks out the soul. It would be fair to say that we were all rather in awe of her. Not a great beauty in any classical style, but noticeable, memorable, one might even say seductive, although seduction was not on her agenda in Anna’s primary-school days. She must have mesmerised the Professor. When she is talking to you, she transfixes you. Her short-sighted eyes are very fierce and piercing, a cornflower-blue. This explains some of her history. Had she not given birth to Anna, her life would have been different. It might have been played at fast and loose.

She wasn’t a great beauty, but she had a style that turned heads, a confident way of walking and of being in her body. I don’t know how a man would describe her, but men (including the Professor, or whoever the Professor represents) were attracted to Jess. If it hadn’t been for Anna, we would have feared for our husbands.

In her new home in Kinderley Road, Jess gave enterprising little suppers at which she amused herself and us by cooking, usually successfully, odd little dishes, some composed from ingredients from the West Indian store round the corner. Her pigs’ trotters were a triumph, and once she ventured on pigs’ ears. She enjoyed confronting taboos. She and Anna were fearless eaters. You need not feel too sorry for Jess. Some sorrow is appropriate, but she was not, as I hope I have made clear, an object of pity. We regarded her with respect, affection and alarm. She was good company. We laughed a lot, over our cheap meals and cheap wine, on our excursions to the park, on our turns on the swings and the roundabouts.

There were park attendants in those days, some of them rather bossy and disagreeable, officious little despots of their small domains, and I remember an unpleasant altercation when one of them reprimanded Anna for tipping some sand from the dog-frequented sandpit on to a miserably bare adjacent flowerbed. Jess leapt to her daughter’s defence with an impassioned speech which impressed and alarmed us all. She was a fierce mother, a cat, a lioness, guarding her kitten. She never allowed anyone to criticise Anna.

And not many wished to do so. Anna was a good girl.

If Jess longed to pursue her academic career more actively, she did not let us know. She did not complain. She appeared to have accepted, on Anna’s behalf, the home front and the life of the mind. She continued to read, to study, to think, to write, to venture into the wilder wastes of intellectual speculation. One can do all those things from a little house in a back street off the Blackstock Road near Finsbury Park tube station, with reasonable access to the SOAS library and the British Library and the Royal Anthropological Institution.

Some think, indeed, that the brain grows keener in confinement. In the field, the brain wanders and cannot settle. As Guy Brighouse’s was so fatally to do.

Jess managed, during this early period of Anna’s infancy, to teach two days a week at an adult education college, and with Guy Brighouse’s help she obtained a generous bursary to write a thesis. Guy looked after Jess well. Her thesis, you may not be surprised to hear, dealt with the assessment and treatment of mental incapacity and abnormality in the area of Central Africa that she had visited in that first youthful escapade into what was not to her the heart of darkness. (Northern Rhodesia became Zambia even as she was working on this project.) She had toyed for a while with the idea of writing about representations of the enfant sauvage in the literature of anthropology, a subject of great cultural richness, but too open-ended for a beginner, or so Guy Brighouse, by now her supervisor, told her. So she confined herself under his not very attentive guidance to the impact of missionaries on the practice of traditional remedies and ‘witchcraft’ (for this was Dr Livingstone’s realm, the land where he strove and died) – and, tangentially, with the variability of the concept of IQ with reference to ‘the savage mind’. (The word ‘savage’ was still, at that period, almost acceptable, although it sounded better in French.) She had to rely very heavily on secondary sources, but she made the best of a bad job.

She had enjoyed exploring the nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century accounts of explorers and big-game hunters and native commissioners, discovered in periodicals and learned journals and government reports. She noted their degrees of condescension and racial prejudice and their appalled condemnation of insanitary living conditions in the African colonies. (The laziness, the dirtiness, the unhealthiness! The smallpox, the jiggers, the worms, the ticks, the syphilis, the scurvy, the leprosy!) She had learnt that the people of the big lake went mad when sent to work in the copper mines, and would not eat of the flesh of the amphibious land-dwelling fish called nkomo, because if you ate of this mad non-fish it would drive you mad. She longed to see a nkomo, but doubted if she ever would.

She had noted that tolerance of mental disability and mental disturbance appeared to have diminished with the advent of Christianity: ‘lunatics’ had rarely been attacked in the old tribal days, as one theory held that if you killed a lunatic, you would catch his lunacy. This superstition had served a useful purpose, Jess seemed to suggest in her thesis, and it was a pity that it had been undermined by science and by the Christian religion.

She now, several decades later, disagrees with her 1960s position. She now thinks that Christianity has had, overall, globally, historically, in Africa and elsewhere, a favourable impact on our perceptions of mental disability and birth defects and congenital irregularities. It has been kinder, for example, to twins and the mothers of twins. Some African cultures slaughter twins at birth. The mothers of twins, like slaves, were attracted by Christianity. They were reluctant to slaughter their babies and glad of a reason to defy tradition.

Jesus did not have views on twins, as far as we know, but we believe we know that he favoured the simple-minded.

Jess was then in most ways a child of her secular, progressive time, and distrusted missionaries on principle. She disapproved of Livingstone as a proto-imperial trader with a gun, as she had been taught to do at SOAS. She did not share his view that commerce inevitably elevated culture. She noted with interest the cool detachment of his comment that ‘the general absence of deformed persons is partly owing to their destruction in infancy’, and his equally detached views on abnormality or transgression summed up in the African term tlolo. But she could not prevent herself from being moved by his tender accounts of the tree-frog and the fish-eagle, the forest and the mountain and the waterfall. He had seen the natural world too closely for any kind of comfort, but he had loved some of its manifestations. Livingstone, like the lobster-claw children, worked on in her memory.

She read his diaries and letters, and worried about the poor orphan Nassick boys, the young Bombay Indians who faithfully accompanied him as servants on his travels. Jess always worried about orphans. She used to try to tell me about the Nassick boys but it was a complicated story and I’ve never worked out quite who they were, though their unhappy name has stuck with me. They hadn’t featured in the school-prize version of Livingstone’s travels that I’d read.

Jess’s supervisor Guy Brighouse had spent some years with a dry, grey-black-skinned, long-legged and dwindling tribe that made, according to him, the most sophisticated pots in Africa, and the most beautiful conical dwelling places man or woman had ever seen, of wattle and decorated clay. These mason–potters were dying out, according to Guy’s theory, through aesthetic despair, as modernity overtook them. Plastic and corrugated iron were killing them. Their hearts and souls were dying.

Jess liked Guy, and the freedom of his fancies. He was considered a wild card at SOAS, but she liked that too.

She managed to work into her thesis a mention of the children with fused toes, but to her regret was not able to find out anything more about them. Livingstone did not seem to have met them, though he noted the dwarf, the albino and the leper, and Guy, who had seen them, did not show much interest in them. Nobody then or now seemed to have studied them. Did they and their children and their children’s children play still by the shining lake upon the immortal shore?

The analogue of the children continued to haunt her. She found documentation of a cluster group of the families of similarly afflicted children in Scotland: the parents had told the eminent investigating statistician that the little ones didn’t miss their fingers and toes – ‘Bless’ee, sir, the kids don’t mind it, they don’t miss what they’ve never had’ – and that they were remarkably adept with the vestigial digits which they did possess, with which they produced fine handwriting and needlework.

Jess had noted how deftly the lake children had punted their small canoes.

Of all the explorer narratives, Jess liked Mungo Park’s best. She was touched by this lone romantic Scottish adventurer’s desire to see the best in others, even in those who were exploiting him, robbing him, exposing him mercilessly to lions and starvation. A child of his time, he wished to believe in the universal goodness of human nature. And he did meet with some goodness in Africa, as well as much cruelty.

Jess liked best the episode when he was denied hospitality and shelter by the suspicious king of a tribe near the Niger and forced to sit hungry all day beneath a tree, and to take refuge at night in its branches from wild beasts, as nobody would give him food or accommodation. But he was befriended by a woman returning from her labours in the field. Observing that he looked weary and dejected, she heard his story with ‘looks of great compassion’, took him to her hut, lit him a lamp, spread a mat for him and fed him with a fine fish broiled on the embers. She assured him he could sleep safely in her hut, and during the night she and her female company sat spinning cotton and singing an improvised song:

The winds roared, and the rains fell. The poor white man, faint and weary, came and sat under our tree. He has no mother to bring him milk, no wife to grind his corn. Let us pity the white man, no mother has he …

This song can bring tears to Jess’s eyes whenever she wants.

The less friendly and more avaricious Moors were puzzled by Park’s pocket compass and the way its needle always pointed to the Great Desert. Unable to provide a scientific explanation comprehensible to them, Mungo Park told them that his mother resided far beyond the sands of the Sahara, and that while she was alive the iron needle would always point towards her. If she were dead, he said, it would point to her grave.

As it happened, his mother outlived him. He came to a sad end, though not on this recorded expedition. He pursued his fate.

Jess found these stories deeply touching.

Mungo Park didn’t think much of the slave-trading, intolerant and bigoted Moors, who hissed and shouted and spat at him because he was a white man and a Christian. They abused him and plundered his goods and refused to let him drink from the well. He had to drink from the cow trough. They ill-treated their slaves and their womenfolk.

He preferred the native Africans with their simple superstitions and their kind hearts.

Mungo Park was an Enlightenment man.

Who could have foreseen what would happen to the Blackstock Road in the next millennium? We didn’t. Nobody did. The mosque and the halal butchers took over from the barrels of salt pork, and young men with beards from the West Indians and the Irish. The friendly Arsenal at Highbury, home of the Gunners, moved to the glittering Emirates Stadium, built and sponsored by money from the Middle East, and Miss Laidman married the head of a college of further education and went to live in North Kensington. The balance of power and the balance of fear shifted. But by this time many of us, like Miss Laidman, would have moved on to more up-market neighbourhoods. Some of us are still there, in the old neighbourhood, and our properties have appreciated a hundredfold, as properties in London do, but the area is still not what you would call fashionable. Those of us who are loyal to it appreciate it, indeed love it. Some streets, with their modest little mass-produced brickwork and tile decorations, have hardly changed at all. There are old lovingly pruned rose bushes growing still in small front gardens. They predate the booms and slumps of property.

Blackstock Road has not yet, as I write, become gentrified, and may never become so. It was peaceful then, when we were young. Shabby, but peaceful. There were little shops, selling small cheap household objects, bric-à-brac, groceries, vegetables, stationery. Locksmiths, hairdressers, launderettes, upholsterers, bookmakers. A lot of people taking in one another’s washing. It is much the same today, although most of the shop-owners now come from different ethnic groups. There are fewer of the old white North Londoners. They are dying off, moving out. It remains on the whole a peaceful neighbourhood, though there have been eruptions of violence and suspicion, and one spectacular police raid by hundreds of uniformed officers that revealed, I believe, a tiny cache of ricin.

Even a tiny cache wasn’t very pleasant, some of us old survivors thought, although we made light of it, laughed about it. It’s not nice to have neighbours who are trying to kill you, even if they are not trying very hard. We tried to be tolerant, but it wasn’t very nice.

There was a time, not so long ago, when hatred was preached by a man with a hook for a hand from the redbrick mosque of Finsbury Park, the mosque that Prince Charles, Prince of Many Faiths, opened with such conciliatory optimism in 1994. It’s quieter now. It’s not a very big mosque, not one of those extravagant imposing new mosques with great golden domes, and its minaret is made of cement and pebble-dash. It is well guarded by spiked walls and CCTV Suburban net curtains drape its windows, with their green-painted frames. It doesn’t look much of a threat. As a mosque, it is a far cry from the glories of Isfahan and Samarkand and Cairo, and I’m not sure who is watching what on that CCTV

You can’t tell what will happen to a neighbourhood. Jess studies its evolution with an expert eye. Her eye is better than mine, but we discuss its progress. I’ve learnt new ways of looking from Jess. She continues to find ways of employing her sociological and anthropological expertise.

Finsbury Park tube station hasn’t seen much improvement. At our age, most of us tend to avoid it at night. It presents a small challenge. Too many drug-dealers. They’ve moved up the line towards us from King’s Cross.

I visited a great and famous mosque in Cairo once. I forget its name. It was unutterably grand and sacred, lofty and empty, austere and sombre. It reared up from the deep ravine of the sloping street like a cliff face. I wandered round its solitude in silence and in awe.

The Finsbury Park mosque is small, domestic, suburban. Rather English, really.

Jess’s thesis on contrasting perceptions of witchcraft and disability in pre-imperial and post-imperial Africa was disputed, and she was rightly accused by some of having bitten off more than she could chew. She was also accused from a diametrically opposite angle by one of her assessors of having failed to include any mention of the superstitions surrounding the birth of twins in West Africa, and the heroic work of Scottish missionary Mary Slessor in rescuing some of these twin babes from being exposed at birth in the bush. (Jess had not mentioned Mary Slessor and the twins because she had never heard of them. Her knowledge, although arcane, was very patchy. But she was still very young. The assessor had himself specialised in Mary Slessor and twin studies, and if Jess had known that she might have been more diplomatic in her selection of material.)

Theses were not nearly as rigorously overseen in those days as they are now, and the maverick globe-trotting conference-attending field-work-dabbling Guy Brighouse had been somewhat nonchalant about his duties towards her. You could get away with almost anything. You didn’t have to tick so many boxes.