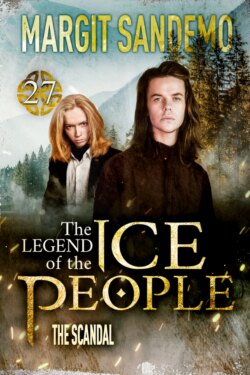

Читать книгу The Ice People 27 - The Scandal - Margit Sandemo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

“I woke up crying but I didn’t know what I was crying about.”

The doctor stared at the slender little figure with ill-concealed impatience. “Your dreams mean nothing. Do you have any pain anywhere?”

She looked at him with her big, dark, violet-blue eyes.

“No,” she said.

I do have pain, she thought. But not in my body.

The room was nice, airy and tidy, decorated in a white and green colour scheme. Outside could be heard the humming of the voices of other visitors to the health resort, and the trickling of water from the life-giving spring.

“Your relatives are concerned about you, Magdalena. I have promised to try to help you, but you are going to have to cooperate. All this talk of unpleasant dreams that you don’t recall is not at all helpful.”

“But there’s nothing else wrong with me!”

“Nonsense! You eat like a bird, you are as thin and pale as a wax doll, and you’re so nervous that you jump at the sound of a needle dropping to the floor. Did you say you are thirteen?”

“Yes, I’ve just celebrated my birthday.”

“Hmm. We’d better bleed you, and you are to drink the spring water. Six glasses a day. Now you can go to your uncle, the consul. He is also very concerned. It was kind of him to bring you here, you should always remember that!”

The doctor ended the consultation with a friendly smile. That is to say, the corners of his mouth went up for a moment. Magdalena thought he resembled a cat silently meowing.

She went out onto the wide, sunny staircase. Outside on the lawn, clusters of visitors to the resort sat on neat chairs around neat tables. Magdalena spotted her wealthy uncle at one of the tables and approached him hesitantly. He was sitting in the company of a woman, and she didn’t want to disturb them.

But her Uncle Julius caught sight of her. Lifting his hand from the silver cap of his walking stick he beckoned her to join them.

“Yes, dear lady,” he said to the major’s wife, “this is little Magdalena.”

Magdalena curtsied to the beautiful but stern-looking woman.

“Dear child,” said the major’s wife, in an overtly friendly voice. “How sweet it is of your uncle to bring you to Ramlösa Sanatorium. It must be so wonderful for you!”

Magdalena couldn’t see what was so wonderful about having to escort her uncle back and forth along the gravel paths, listening to his huffing and puffing and the other sounds he made after eating too much. There were no children for her to talk to here, except for an unpleasant little six-year-old who was always following her around and tugging at her long dark hair, or trying to throw mud at her chalk-white pantalettes.

Otherwise there were only elderly people, suffering from ailments both real and imagined. And the conversations at the dinner table mostly dealt with toxins or bloated stomachs or osteoporosis or miracle diets to combat consumption, and the ladies would swoon in their tightly laced dresses, which made it almost impossible for them to eat, and the men would steal cups of punch on the sly even though they weren’t allowed to. Magdalena wasn’t allowed to say anything, only to the doctor, whom she didn’t care for, so she withdrew completely into herself in this very distinguished setting.

But she had been doing the same thing at home lately. Ever since ... well, ever since what? Since when? She couldn’t eat anything and didn’t dare sleep.

“Oh, I left my parasol on the veranda,” said the major’s wife.

“Magdalena will fetch it,” said Uncle Julius.

Magdalena was already on her feet, as she knew that her uncle would ask her to get it. No, he would order her, take it for granted that she would.

The building with its white veranda was beautiful. It was yellow and surrounded by lilac bushes with heavy, blue-violet flower clusters, which went beautifully with the colour of the walls. Everything was so nice here! And deadly dull.

As she was on her way down from the veranda with the pink parasol in her hand, she heard a cry for help.

Round the bend on the path leading to the steps came an odd-looking equipage.

An elderly man was clinging to his wheelchair, emitting small, helpless cries from his gaping, toothless mouth as his chair was pushed along at a frantic pace by a boy of about Magdalena’s age. The happy boy’s face shone with excitement at the speed, and after an over-confident turn the chair screeched to a halt in front of the steps. The man tipped forward at what looked like an alarming angle, but the boy straightened him up effortlessly. The old man was so shocked that all he could do was whisper what was supposed to be a scolding.

“My pleasure,” said the boy with a smile. “I bet you’ve never been driven that fast before!”

The doctor came rushing out to welcome the old man, giving the boy a series of reproachful looks at the same time. Some portly, well-fed nurses came storming out as well, cackling and crossing themselves.

Magdalena had stopped on the bottom step and she stared at the boy. His hair was fair and tangled and unruly. His eyes were the most joyful and vivacious Magdalena had ever seen.

He can’t be ill, she thought.

And he wasn’t. A man came up behind him, walking on crutches.

“Goodness, Christer!” he said, horrified, though Magdalena could hear the suppressed laughter in his voice. She herself was having such a hard time keeping a straight face that she had to purse her lips.

But her eyes betrayed her. Christer, the boy, had noticed her and shared in her amusement. He let the ladies cackle on as he eyed her dreamily.

“Oh, Father, look! Isn’t she the most beautiful girl you’ve ever seen? I think I love her!”

“Honestly, Christer!” his father said, and she had the impression that that had been the father’s standard comment throughout the boy’s childhood. “Dearest Christer, you can’t say that sort of thing to a young lady. Please forgive my son, Miss, he tends to be a little impulsive, but he doesn’t mean any harm by it.”

Magdalena had lost her ability to both move and speak. She was completely spellbound by the newcomers. The father’s friendly eyes. And the boy ... imagine being allowed to talk like that to one’s father! Magdalena would never have got away with that at home.

Meanwhile, for quite some time she had been vaguely aware of a furious voice shouting: “Magdalena! Magdalena! Are you bringing the major’s wife’s parasol or not?”

But she had deliberately ignored Uncle Julius. She wanted to have this moment to herself. She’d just have to deal with the punishment afterwards.

But now she couldn’t stay there any longer. She gave young Christer one last shy glance before running off to her own private doomsday.

“I’m sorry, Father, but I just couldn’t resist that wheelchair,” she heard Christer saying behind her.

As predicted, she was grounded. Uncle Julius took her by the ear in the most humiliating way and dragged her past all the gawking, gleeful resort visitors and into the house. As she passed Christer and his father – the only two faces that expressed any kind of sympathy – the boy hastily whispered, “Don’t worry! I’ll help you, because I can do magic!”

Confused and uncomprehending, yet still grateful, Magdalena was conducted to her room by the iron hand of her uncle who subsequently, with fury and self-righteousness, locked her in.

Christer was helping his father move into Ramlösa Sanatorium.

Christer had always had an extremely good relationship with his parents: the quiet, disabled Tomas and Tula, the wild – yet temporarily tame – Tula of the Ice People. She had been behaving in an exemplary way for the sixteen years that she and Tomas had been married. It was only when she was with Christer that she revealed a little of her hidden thoughts and feelings.

She and Christer were the best of friends. Tomas did not know that she was giving the boy some strange ideas during their private chats, and that was probably a good thing. She had disclosed to her son that she could do magic. She could tell him the most amazing things about the Ice People, and every so often she had showed him some simple spells that left him lost for words. She quickly discovered that he was a bit too fascinated by occult magic, so she stopped “boasting” about it and asked him to forget what she had said. But, of course, Christer could not forget it.

He didn’t ask any more questions about the magical secrets. He stopped talking about them. But he was convinced that he was the only one in the family who would continue the legacy.

When he was six years old he tried to get the dog to lift itself up from the ground and fly with its ears revolving. He didn’t succeed, of course, but Christer could have sworn that the dog had raised itself on its toes, and hadn’t it also waggled its ears?

Christer had a vivid imagination.

When he was seven years old he shocked the cook by going into the kitchen and mumbling something threatening over her consommé. That was, of course, on Count Posse’s estate, Bergqvara – where any ordinary soup was called a consommé – and the boy would run in and out of the kitchen as if he was one of the staff, because Tula often helped out on busy festive occasions and had to take her son along with her. This time he believed that if he recited all the magic spells he knew over the soup, everyone at the banquet would change their hair colour. He just wanted to see what it would look like – he hadn’t thought much further than that. Nothing happened to their hair, of course, but that was only, he believed, because the chiming of the clock had interrupted him as he was reciting the most important of the spells.

These spells and incantations were mainly of his own invention, for Tula had been smart enough not to reveal the most secret of them to her son.

His attempts at hypnosis were numerous and each just as futile as the last. But that didn’t bother him in the least. Christer had an unwavering belief in himself. Like the time the farm manager had scolded him for plaiting the horse’s tail into “troll braids” which, of course, had had no effect. Then Christer had turned on him, his brows knitted in a threatening expression as he pointed an imaginary pistol at him. “Bang, bang, you’re dead!” the boy roared, self-assuredly. The manager had a sense of humour and decided to join in the game. He dropped theatrically to the stable floor. Christer froze in horror, and was about to rush out of the stable but then he decided to acknowledge his responsibility. He recited a few well-chosen spells over the unfortunate man, who immediately woke up again. To Christer’s great relief.

But Christer was shaken. I’ve inherited some dangerous skills, he thought, breathless with excitement. I’d better be careful how I use them!

So after that he didn’t cast so many spells. But the fact that Grandmother Gunilla’s vegetables were unusually sumptuous the following year, was, of course, down to his magical skill and not because they had been given a pile of first-class horse manure from the stable. And it was also Christer’s doing that Grandfather Erland’s shoulder got better, was it not? Because hadn’t he smeared a healing ointment of his own concoction on a stick and recited a few magical words?

But he didn’t tell anyone about it, of course. It was his big secret. That he was the next chosen one of the Ice People. Because he was chosen and not stricken – that was clear from all the gifts with which he had been endowed. His mother was stricken, she herself had told him so and he had seen numerous instances that showed it was true. She had changed over the years, as both Christer and his father had noticed. She might not have been as attractive as when she was younger, but she was much more fascinating. Her eyes gleamed magically at times, almost as though they were made of gold, and there was something devilishly attractive about her that made people turn their heads when they passed her in the street. Her hair was much darker now. Christer remembered a time when it was almost golden. Now it was very dark blonde. But it didn’t matter, because she was his mother, the most understanding person in the world.

And she was so sweet to his father! It was always so wonderful to watch them together and to see the love between them. His mother, who was really a restless, impatient type of person, fussed over his father even more now that rheumatism had seriously spread throughout his body. It was a direct result of the many injuries he had received as a child while pushing himself around on his little cart, and the exposure to wind and cold he had had to endure. His mother gave his father ointments to rub on his aching joints, but she didn’t have that much and Christer had once heard her cursing Heike because he wouldn’t give her the Ice People’s treasure. He had also heard her whispering strange incantations over Tomas’s body, which seemed to help a little but not much.

For that reason they decided that Tomas should try staying at the Ramlösa Springs for a little while. It had been Count Arvid Mauritz Posse who had suggested it. He had been Tula’s childhood friend and was now one of the most important men in Sweden. And Tula, who wanted the best for her husband, let her son accompany him. She couldn’t join him herself because they were busy moving from Bergqvara. But more about that later – right now the stay at the Ramlösa Sanatorium is what is most important.

Little Magdalena Backman sat on the edge of her bed with her hands in her lap, swinging her crossed feet. She was tired all the way to her child’s soul from all the demands that were placed on her.

There was a discreet knock on the window.

She looked up with surprise but couldn’t see anything except the hand that was knocking eagerly yet quietly. It was night, but just as light outside as during the day.

Magdalena got up hesitantly and went over to the window to look out.

It was the boy from earlier, called Christer. He gestured to her to open her window.

She cast an anxious glance behind her, but she knew that Uncle Julius was in the drawing room drinking punch with the other gentlemen. She could hear them all the way from her room, their roars of laughter and the coquettish chatter of the women in the room next door to the men. Usually anxious, for once she forgot all about her fears and struggled impatiently with the window catch. Finally the window opened.

“Come outside,” Christer whispered.

She looked around.

“They’ve started playing cards,” he said reassuringly, “But arrange your bedclothes just in case.”

“What do you mean?”

“Put something under the duvet so that it looks as if you’re lying there asleep!”

Magdalena grasped what he was saying. This was exciting!

When she had arranged the bedclothes she tiptoed back to the window.

“But how am I to get out? The door is locked and Uncle Julius has the key.”

“Through the window, of course! Come on, I’ll catch you.”

He stretched his arms temptingly towards her.

“But ...”

Her thoughts were running wild. Up in the window. My skirts. Can I hold onto them? How shall I ...?

“Come on, jump! It’s not very far down!”

He was right. But Magdalena, in the name of decency, attempted to crawl out, with one foot at a time, which, of course, went completely wrong. Her skirts rode all the way up as she landed rather helplessly right in his arms.

“As light as a feather,” he said effortlessly. “What do you live on? Pollen?”

At this very moment, as she lay in his powerful young arms, he became her idol and hero. For Magdalena had been a very lonely child.

He put her down carefully and took her hand. They quickly ran through the dewy grass among the beech trees at the back of the main house until they disappeared from view of the resort buildings.

“I can’t stay out very long,” Magdalena whispered. “Uncle Julius doesn’t usually come into my room, but he will hear when I clamber back inside.”

“We’ll work something out.”

How thrilling this was! Magdalena was so overexcited she could barely breathe. The boy found a pile of logs and arranged a place where they could sit down. He cleaned the spot with his handkerchief. Magdalena sat down carefully. She had the feeling that she was taking part in something truly scandalous, but she didn’t regret anything.

“You see, I’m going back tomorrow morning,” Christer said. “And I wanted to talk to you before then because I thought they treated you so badly. I wanted to see if I could help you.”

She experienced everything very intensely, as though she wanted to absorb every single drop of this moment. The gnarled yet smooth tree trunks, if they could be described in such contradictory terms, the light green foliage that formed a canopy above them, the tree she was touching with her hand, the grass against her boots and, not least, the boy sitting next to her. She had never imagined that such powerful currents could flow between two people. It felt as though she was being stung by small, fine needles of delight. She was so fervently aware of his dishevelled hair, the cheerful, deep-set eyes, the teeth with great gaps between them, the slightly upturned nose. His face was harmonious, perhaps mostly because it expressed a friendliness that was genuine.

Magdalena wasn’t accustomed to genuine friendliness.

“Is it true that you can do magic?” she asked shyly, blushing.

Christer tried to look nonchalant, but he didn’t quite manage it. “Oh ... no, it’s nothing special,” he said indifferently, waving the idea away with a lavish movement of his hand. “Let’s focus on you. Why are you here?”

She bowed her head. She didn’t want this charming boy to leave.

“They say I must be sick because I don’t eat anything. But it’s not true. I’m just very scared.”

Christer couldn’t recall ever having seen such small, fine feet in such high, black, buttoned boots before. He took her hand in his. “What are you scared of?”

His hand felt strong and warm.

“I don’t know. Of my dreams.”

“Are they frightening?”

“Yes, but I can never remember what they’re about. It’s as though they’re trying to ... hide.”

Christer tried to look intelligent. “I know what you mean. I don’t think it’s the dreams that you’re afraid of. It’s something else. I think there’s a dark spot in your life.”

This wasn’t something he had thought up on his own, he had heard Heike use the expression once. But it sounded so good that Christer adopted the impressive theory as his own.

His words frightened her. “I don’t like you saying that. It just makes me even more scared.”

“Do you have such a dark spot?”

“I don’t know,” she said despairingly. “Oh, I wish I were dead!”

“No!” Christer gasped. “You mustn’t say such things! You are the prettiest thing I’ve ever seen!”

She calmed down. “No, I find that I don’t want to die after all,” she said, thoughtfully. “But I discovered that on my way here,” she continued, stamping on Christer’s staggering notion that it had been the discovery of his existence that had changed her mind.

“Really?” he said, somewhat hurt.

“Yes, as we were riding along a deep gorge, our carriage lost a wheel and I clung on so hard that I realized that I must want to stay alive after all. The only misfortune that occurred was that Uncle Julius’s sturdy lunch basket tumbled into the void. Which wasn’t so deep that the coachman couldn’t clamber down and collect the cheese and sausage that had been scattered over the entire slope.”

Christer laughed. The girl had a sense of humour as well. She was ... wonderful! The fine little nose. The radiant eyes. Oh, how he loved her!

“How ... old are you?” she asked shyly.

“Me? Oh, let me see. I was born in 1818 – that’s easy to remember. And now it’s 1833 ... so that makes me fifteen.”

He knew perfectly well how old he was, he just wanted to bask in the interest she was showing in him for as long as possible. She seemed to be impressed by his awe-inspiring age.

“Where do you live? I mean, when you’re not here?” he asked.

She grimaced. “We live in a big house near Stockholm. It’s terribly refined. It has a park so big that you can get lost in it. But there is a high fence around it so it feels as if you’re in a cage.”

Wealthy, in other words. Christer sighed inwardly. His own parents were far from rich ...

His thoughts were interrupted.

“And where do you live, Christer?”

She had said his name! With a little lisp, in her clear, light voice she had said his name! He could have died from sheer happiness.

He waved his hand nonchalantly. “Oh, I ... live in Wexiø. But we’ll soon be moving from there. Up to the Stockholm area, in fact.”

“You will?” she asked, brightening up. “What does your father do? He looked so friendly.”

Christer repressed the urge to make his father sound richer than he was. “Yes, he’s the best father in the world. He is an instrument maker. Very skilled.”

“And your mother? Is she just as nice?”

“My mother?” he said, laughing. “She’s completely wild! She can do magic. And she spoils me. I adore her!”

He sensed that her voice had grown peculiarly miserable. And she confirmed his suspicion by saying, “You are so lucky, Christer!”

He looked deeply and with sympathy into her eyes. “Aren’t your parents nice?”

“I don’t know,” she said miserably. “I don’t know them!”

“You don’t know them?”

“Well, I do. My mother, she’s not my real mother because she’s dead, she’s only my stepmother. She’s probably nice enough – she’s never been mean to me in any way. But I ... how can you know someone who only comes twice a day to kiss your forehead and ask how you are? Who stays with me for half an hour in the evenings to ‘associate’ with me. We have nothing to say to each other, and it always ends up feeling so stiff.”

“And your father?”

Magdalena turned her head away. “I never see him. He’s never at home, and when he is he just greets me indifferently. He’s furious with me for not being a boy. But now he has the boy he wanted, and he smiles at him and talks to him. Father is a trade consul.”

Christer had no idea what that was and he didn’t dare reveal his ignorance by asking her. But it sounded very distinguished.

“Is there no one who cares for you?”

“Yes, Grandfather is nice. But he’s so old and doesn’t see or hear very well any more, so it can be difficult to talk to him.”

Christer nodded solemnly. “I understand. Older relatives can be very good for one. I was close to my great-grandfather. But he died last year and I grieved terribly. I’m still in mourning.”

Magdalena gave his hand a squeeze. “I think you’re so sweet, Christer! Can’t you stay here?”

“If only I could!” he answered fervently. “But Mother needs my help with the move. But what is your Uncle Julius like? He seems strict.”

“He is strict. I don’t know why he brought me here, because he’s never concerned himself with me. But, of course, I am good at running errands for him.”

“And your little brother?”

She let out an impatient sigh. “Of course I love my little brother! But he isn’t even a year old yet and I’m hardly allowed to see him because they think I have lung disease. But I don’t!”

Christer himself had assumed that she must have consumption because she was so skinny and pale. But now he was beginning to understand the whole situation better. A plant that isn’t tended will wither. He noticed that Magdalena had many fine clothes and lacked for nothing in terms of material things, but where was the human companionship and love in her life?

“You must be terribly lonely,” he exclaimed.

She lowered her eyes. “Yes,” she whispered. “I often think about that when I’m walking around the park to get my ‘daily exercise’. My only friend is my little dog Sascha, and I miss him terribly now. I hope they’re being nice to him.”

She pulled herself together. “But you said you could do magic,” she said. “Conjure up some happiness in my life, Christer! And make the scary dreams go away.”

Christer thought back with displeasure to the time when he had tried to get that revolting breakfast to disappear. He had made magical movements with the porridge dish. His father had got rather angry and told him to remove the blobs of porridge from the ceiling and his hair.

“I will,” he said resolutely to Magdalena. “You can count on me. Actually, abstract magic is my forte. I will make your parents realize what a wonderful but lonely girl they have in their house. And make all your bad dreams disappear. I normally use incense for that sort of magic, but it won’t do here ...”

For a moment he remembered the time when he had come close to setting fire to Grandfather Erland’s house in order to spirit away his grandfather’s headaches, which he always suffered from on Mondays. Christer had decided then never to use incense again when doing magic. Especially after Grandmother Gunilla told him that his grandfather’s headaches were self-induced and derived from the schnapps barrel. But she said it with affection, for she allowed Grandfather Erland to enjoy his schnapps on Sundays. He was so infinitely sweet and caused no harm, except to his own head.

“If you can’t use incense, how are you planning to conjure away my dreams?” Magdalena asked shyly and with admiration.

“It’s hard to explain to someone who hasn’t been initiated,” Christer said. “I have my secret formulas.”

Yes, he most certainly did. But they were pitiful and homemade. His mother, Tula, had been so petty as to keep hers to herself.

Magdalena gave him a devoted look and Christer could almost feel himself growing taller. He was unsurpassed, invincible; he could do anything!

“Trust me,” he said, patting her hand. “My magic never fails.”

Ha! It hadn’t worked a single time. Except in Christer’s imagination.

“But how is it that you can do magic?” she asked with childish faith.

“It’s a secret really,” he said in a voice that was mysteriously hollow. “But I’ll tell you anyway. I belong to a family called the Ice People.”

“Oh, that sounds frightening!”

“Yes, many of my ancestors were witches and sorcerers. They got burned at the stake and that sort of thing. But most of them are exceptionally good people. I have a relative called Heike who’s almost better than me at doing magic. But he only conjures good things, never black magic. Like me.”

“You’re so good!”

Yes, Christer was about to say, but he managed to stop himself. “That’s how we are,” he said, casually. “We can’t help it. But it’s starting to get cold. You mustn’t get chilled.”

She got up reluctantly. “Oh, I don’t want you to go! My life will be twice as empty now.”

He felt that way, too. “I can write to you!”

At first she brightened up at the idea, but then her delicate little face grew sad again. “No, that won’t work. They read my letters and they would get that sorrowful, reproachful look in their eyes that they usually adopt to make me feel guilty. I probably wouldn’t be allowed to read your letter. But I could write to you!”

“Yes!” Christer shouted. “Do! Tell me how you are, whether your dreams have started to go away. But ... I don’t actually know the name of the place where we are moving. It’s south of Stockholm, that’s all I know.”

“And I live to the north. But couldn’t I just send it to your old address?”

“Yes, of course! Then they’ll forward it!”

He told her the address, which she repeated many times in order not to forget it. Feeling much more at ease, they returned to the house. They still had some sort of future with one another.

Christer helped her get back up into the window and then she reached out her hands to him to thank him. He kissed them carefully as he had seen gallant men do. Magdalena sighed dreamily.

“My friend,” she whispered.

Consul Julius Backman looked at the doctor expectantly. “Well?”

It was the following day. The doctor puffed at his cigar as he gave the well-fed man a sly glance.

“She seemed happier today. More open. She’ll recover.”

“Fine,” said the consul. “Keep me informed. Her parents are absolutely determined to find the cause of her delicate state of health.”

“Yes, of course. We all have the best of intentions for our little Magdalena, don’t we?”

“Of course we do,” Consul Backman nodded heartily.