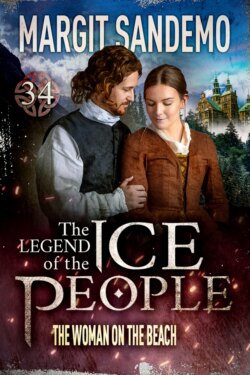

Читать книгу The Ice People 34 - The Woman on the Beach - Margit Sandemo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

The Ice People knew that many dangers lurked. They were a vulnerable clan because they had links to both the real and the shadow worlds. It was their own ancestor, Tengel the Evil, who posed the greatest danger, but others were also after them for various reasons.

Somewhere deep inside a forest, something was waiting for a very special member of the Ice People. The evil had waited for years in the dense forest, brooding on revenge in a yet-to-be-accomplished vendetta. The evil deeds of the fathers. An unforgivable offence that had to be accounted for.

There was a small, swampy forest lake, almost overgrown – a pool that reeked of evil because of what was hidden at the bottom.

It was virtually impossible that that particular descendant of the Ice People should find the way to this very spot deep in the forest ...

And yet it happened.

A hundred and fifteen years had passed since the offended party had suffered the deep humiliation that led to the vendetta. It was many hundreds of years since the first offence, which triggered it all, was committed. The Ice People hadn’t been involved, at least not from the beginning. A century ago, however, a mere coincidence had brought them to this spot to take almighty revenge.

And now, in 1912, another member of the Ice People was to be led here, not so much by coincidence but out of curiosity.

Precisely the person whom Tengel the Evil was out to get!

André, the son of Benedikte and Sander, wasn’t exactly one of the brightest of the Ice People at school matters. This was something that upset Benedikte, because in Sander’s family there were a great many professors.

“Now you’re talking nonsense,” said Sander. “There are sharp minds among the Ice People, too. What’s so special about being intellectual? It often leads to snobbishness, as I’ve seen among the members of my family. André is fine as he is. If he enjoys working with cars and engines, then let him! I’m really proud of him – aren’t you?”

Yes, she was. Absolutely! They put André’s miserable school report aside and let him do as he wanted.

In 1912, when André was twenty years old, there was much unrest in the world. Relations between Europe’s five superpowers – England, France, Russia, Austria-Hungary and Germany – were extremely tense. Norway was fairly calm at the time, a relatively new nation busy getting itself in order as best it could. The emphasis was on social responsibility. There was so much that had to be restored after six hundred years under foreign rule: industry, agriculture, fisheries, cottage industries in danger of dying out, alcohol policy, the women’s movement, religion, language, schools, party politics, culture, children’s welfare ... There were thousands of loose ends to tie up before the country could be united in one whole. The Norwegian people had plenty of restored patriotic pride.

The people of Linden Avenue did what they could to help create an orderly community. Nevertheless, the Ice People had always lived on the outside. They had stuck together. They had their own heritage, which they preferred not to talk about to others because it hampered their relations with the outside world. It wasn’t that they thought they were more interesting than other people. Rather, they felt that they were slightly vulnerable. Despite the fact that they were very proud of their clan, they felt that they weren’t fully accepted. Perhaps they were over-sensitive, because the truth was that they tended to be thought of as decent and honest but perhaps ... slightly eccentric?

That was something they would have to live with.

André had often thought about Imre’s prophecy that he would be the one who would find the stricken descendant of their generation. Now and then, it had occurred to him that it might be himself. However, he had reached the conclusion that this was out of the question. So had Vanja’s young daughter Christa, whom André had seen far too little of, sadly, because her stepfather Frank insisted ruthlessly on his parental rights. The only exceptional thing about her was the insignificant cleft in her tongue. Otherwise, she was human; nobody would ever have suspected that her real father was a demon.

Least of all Frank ...

Frank sometimes managed to annoy some of the Ice People. They were aware that they could kill his joy in being a father with just a few words. But they didn’t do so. It was a pity for Frank. It had always been a pity for Frank. And they had to admit that he had brought up his daughter Christa very well indeed.

André observed Vetle closely. He was the son of Christoffer and Marit. The boy was now ten years old and a scamp, full of mischief. But was he one of the stricken or chosen? No, it didn’t seem so. André waited for a long time before passing his final verdict.

Then he went to talk to his mother, Benedikte, and his grandfather, Henning, because he regarded them as the most important members of the family.

One evening late in winter, they were shivering slightly despite the stove’s valiant attempts to warm up the old living room at Linden Avenue. However, the cold outside was harsh, and found its way mercilessly through the cracks around the windows, which couldn’t be closed tightly. Benedikte’s tray of tea and freshly baked scones did a lot to mitigate the cold draught in the room.

“I’ve examined all three of us now,” André said. “Vetle, Christa and myself, and I can assure you that none of us is either stricken or chosen.”

“Who did you suspect the most?” Benedikte wanted to know.

“Vetle, but I’ve been keeping an eye on him for years, asking wily questions by setting up psychological traps for him, and there’s nothing there.”

“What is your conclusion then?” asked Henning.

André paused as he dipped his scone in his tea, so that the butter floated in shiny circles. “Probably the same as yours.”

All were silent for a while, hesitating to broach the new problem.

Finally, Benedikte spoke. “That woman Vanja met thirteen years ago, on the beach by the Trondheim Fjord, gave birth to a strange-looking child.”

“Yes,” Henning replied, “and with features similar to those of many of the Ice People. I’ve thought about that incident a lot. The woman or the child’s father could have been descended from the Ice People.”

All three looked at one another.

“Then we know who we’re thinking of,” said Benedikte.

“Descendants of Christer Grip,” murmured André.

Henning replied: “So far, we have heard nothing about him or his possible descendants. But it’s certainly a possibility.”

“If so, we may have lots of relatives,” said Benedikte.

“That may not be the case. The Ice People never have many children. They tend to have only one child.”

Benedikte summed up. “Let’s wait and see! Christer Grip was two or three years old when he disappeared in ... 1777, was it? Well, yes, thereabouts. A rich man took charge of him and travelled up towards the area around Stockholm. It’s a great leap in time and space from there to a poor girl on a beach by the Trondheim Fjord.”

“If you are to begin searching, André,” said Henning, “you can use Christer Grip and his era as your point of departure. Although back then, every possible attempt was made to find him.”

André nodded. “I must begin with the woman on the beach. And then work my way backwards in time. I don’t think I’ll get very far.”

“I’m afraid you’re right. All we know is that her name was Petra and that everybody let her down.”

André got to his feet. “Wait. I’ll fetch the book in which Vanja wrote her account.”

“Fine.”

André was soon back with one of the thick volumes containing the history of the family.

“Let’s see,” he said as he turned the pages. “Here it is. Vanja certainly had beautiful handwriting.”

Benedikte sighed. “Yes, poor Vanja! My little sister, whom we couldn’t do much for!”

“I think she’s doing fine where she is,” Henning said calmly. “However, at the time when she met poor Petra by the Trondheim Fjord, she must have been fifteen years old. Vanja, I mean.”

“Yes,” André replied. “That was in 1899, thirteen years ago, when Petra was seventeen.”

“Poor little girl,” murmured Benedikte.

André read to them: “Petra was a sweet, simple, naive girl. Naive in the best meaning of the word. Things must have gone wrong for her at an early age. Her first child had been taken from her. To the or ... I didn’t catch what she meant. But she was stigmatized while the child’s father – a distinguished married man with a liking for innocent young girls – went free. A civil servant whispered to me that he was considered a real charmer who had a way with the ladies. The father of her second child was a lad who worked at the local foundry. But his parents wouldn’t allow him to marry the girl, especially as she had such a bad reputation.”

“Good gracious!” muttered Benedikte. “Those moralists, what do they know?”

André continued to read from Vanja’s account. “I didn’t get to know very much about Petra, either from her or from anyone I spoke to afterwards. Her name was Petra Olsdatter and she was from the area around Trondheim. I believe her mother came from a good family, but she died young. The father turned out to be a drunkard who neglected Petra. He was livid the first time she got pregnant and chucked her out. Since then, nobody had cared for her.”

“Good God!” whispered Benedikte.

Henning sighed. “We didn’t get much information there. But at least you have something. After Petra’s death there was a hearing, so there must be a record of the court proceedings or something like that. Hopefully, that will give you more leads.”

“Yes,” said André. “That also occurred to me. So do you think I ought to go to Trondheim?”

They looked at him. André was a handsome young man with medium-blond hair and eyes that were steadfast and honest. They had thought he would grow up to be extremely handsome, but during his teenage years his features had become sharper, so that now he resembled Benedikte just as much as Sander. But the overall impression was just fine. He had thick, curly eyebrows, a generous mouth and a nose that could have been better shaped but fitted into the general picture. His hands were big and looked as if they would be good to hold onto. There was something sedate and steady about him. The first impression you got of André was that you could trust him, which was probably quite true.

Unlike Vetle, who didn’t seem quite so trustworthy.

Henning said to André: “I think you should be on your way.”

“Yes, I think so, too,” said Benedikte.

André seemed relieved. He liked the idea of the adventure.

“I suppose you’ll go by train?” asked Henning.

André hesitated. “I ... don’t know. You see, I’ve saved some money ...”

His mother understood what he meant. “An automobile ... a car?”

“They’re awfully expensive,” André said hurriedly.

Henning and Benedikte looked at each other.

“Can you drive properly?” Henning asked. “Cars go fast, you know. At many kilometres an hour, they say.”

“I’ve tried driving Christoffer’s car,” said André. “It’s no problem. Perhaps I could ask for permission to borrow that one?”

“No, I don’t think so,” replied Henning. “Christoffer needs it himself, and cars aren’t toys. I believe I can spare some money and your mother might also have some put by. Isn’t that right, Benedikte? Should we let the boy have his way?”

“We’d better talk it over with his father first,” said Benedikte. “But Sander is extremely fond of cars so ...”

André looked from one to the other. He smiled from ear to ear.

André drove through Sør-Trøndelag in his new car. When he had set off, it had been polished and smart. Now you could hardly see the colour and it creaked worse than an old church organ. Twice on the journey, it had ground to a halt because it had run out of petrol – it was too far between petrol stations – and he had had to push it or walk several kilometres.

Now he was getting closer to his objective.

The car, as André preferred to call it in the modern way, was a Ford Model T, straight from the factory. It was tall and black, open but with a roof over the driver’s seat. Inside, it had leather upholstery, well-padded and elegant, and it had light pneumatic tyres and a horn, which André used quite a lot, especially if young girls were crossing the street ...

He was immensely proud of his car. Admittedly, he had to share it with his father, but this was the maiden journey for the car and for André. There were probably only five hundred cars in the whole of Norway, and when two of them belonged to the Ice People, they could be said to be well off.

To begin with, André sang aloud behind the wheel because he felt so happy and elated. He was a king, he ruled the road, and the whole world was his oyster. As time went by, he became a bit subdued, because it wasn’t always easy. The roads were terrible in places. And then he feared that he might run out of petrol. There had also been a slight problem with the engine once, but André’s technical skills had helped him there. He had been out in the wilderness near Dovrefjell, and had repaired the fault himself. That had boosted his self-confidence.

It was fun to cause a sensation along the small village roads.

Sør-Trøndelag ...

The Valley of the Ice People.

No, André didn’t have to search for that, he had no yearnings in that direction. Especially after what Vanja had told him about it. All the Ice People should stay away from it ... until the right one came along.

But naturally, André kept an eye out to the west! Might it be there? Or there?

He didn’t see any mountains that were high enough.

When he reached Trondheim the first thing he did was to go to a hotel. Since he had a new (albeit dusty) car, he was greeted with bowing and scraping and given a nice room. Throughout his journey, André had discovered how useful it was to have a car, and not just on the road. A car meant status. And his mother, Benedikte, had seen to it that he was nicely dressed, which also added to the good impression he made. André’s trustworthy personality and his openness did the rest.

There was no need to tell anybody that he was only twenty.

After he had taken a bath in the bathroom at the far end of the corridor, which had wooden boards on the floor and a high-sided bathtub with lion-claw feet and gurgling water pipes, he put on clean clothes and ate a good lunch in the almost empty dining hall. On a podium in the corner, surrounded by potted palms that tickled their hair, a sad-faced trio was mangling a Viennese waltz. When André arrived, the players tried to satisfy his youthful taste with a rendition of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”. André had never heard anything played with such a miserable rhythm.

After lunch, which was really good, he asked the way to the municipal offices and thus began his search for Petra Olsdatter’s family tree. Or that of her stillborn child.

He spent a while being sent to various branches of the town council before he arrived at the right place. A woman in a black, high-necked dress and a dangling lorgnette greeted him. André, who had respect for ladies with the courage to do a job like hers, treated her politely, which she liked.

“I’m looking for a distant relative of mine,” he said. “In order to make headway, I need to start with an interview that took place in the courtroom here in Trondheim in 1899.”

“I see. What was this interview about?”

“A young girl, Petra Olsdatter, committed suicide down on the beach on 14 July 1899. My second cousin, who was present, tried to save her unborn child, but in vain. However, young Petra managed to say a few words that indicated that either she or the unborn child was part of our family.”

The lady, whose age was difficult to establish, was already turning the pages in the record book.

“But both of them are dead, are they?”

“Yes, but it has to do with an inheritance,” lied André. Or maybe that wasn’t a lie because it did have to do with the evil legacy. “I need to find out whether there are other relatives. I need to unravel Petra’s or the child’s genealogical lines.”

Now the lady had clearly found the court record, because when she had read a bit, she looked up at André, baffled. He could read her reaction in her face: could this well-dressed, polite young man really be related to such a simple character as Petra Olsdatter seemed to have been?

André answered her unspoken question: “We can’t always decide our own fate.”

“True, true,” she muttered. “But perhaps you would care to read for yourself what it says?”

“Yes, please.”

“That’s fine, provided you sit at the table over there and the records don’t leave this room.”

“Thank you. Is it all right if I take notes?”

“Of course.”

In the quiet hall, where all that could be heard was the scraping of the secretary’s steel pen and scattered remarks from a couple of low-voiced visitors, André went over the entire tragic incident once more. It was a strange, sad feeling seeing Vanja’s name written there: it was mentioned several times.

He knew most of what was written in the records, but he searched eagerly for any new information he could get hold of.

He found Petra’s last address and that of her childhood home. Good! And even better, the name of the baby’s father was mentioned. Egil Holmsen. His address was also given. All this was helpful. There was even a brief reference to Petra’s earlier trouble: “She had got involved with one of the well-established and reputable gentlemen of the town.” André frowned. Of course, his name wasn’t mentioned. Oh well, he wasn’t important, because it wasn’t his child that might be a stricken member of the Ice People. André needed to get in touch with Egil Holmsen, the father of the second child. And, of course, Petra’s relatives. The genes might have come from the mother. It seemed an extremely difficult task: André’s search would have to go back to the 1700s, or rather the early 1800s, because if Christer Grip was born in 1774 he must have lived well into the following century.

André started when the sombrely dressed woman spoke, and he realized that he had been staring into space for many minutes.

“Sorry,” he muttered, “I didn’t hear what ...”

“Did you find anything?”

Despite her strict dress and extremely reserved expression, there was something pleasant about her. Perhaps in her voice or movements? No, both were equally awkward and serious. He looked at her more closely. He guessed her age to be between forty and fifty. She was probably not married. Her grey-blonde hair was combed back a bit too tightly and arranged in a knot, and her features were by no means special but quite refined. There were signs of wrinkles around her eyes, and small downward lines at the corners of her mouth. Not a person you would look at twice.

“Thank you, now I have several addresses that I can use,” he replied.

Her voice sounded more genuine than her words: “If I can be of any help, then ...”

“Thank you, but I can’t take up your time on this.”

She grimaced slightly. “Oh, my work here isn’t all that exciting.”

So she was human after all, was she?”

“Well, in that case ...” André smiled quickly. “May I ask you a question?”

“Certainly.”

André showed her the notes he had made at home. “Look, it says here that little Petra mentioned something about her first child. ‘At the or ...’ What does that mean?”

The woman was quick on the uptake. “Undoubtedly the orphanage.”

“What sort of place is it?”

“It’s a home that takes in neglected children. A place with a very bad reputation. As a matter of fact, I don’t know whether it still exists because there were plans to demolish it. It’s called a children’s home now, but the old name sticks to the horrible place. There’s an error here.”

“What? Really?”

She pointed with her index finger at André’s notes from Linden Avenue. “Here it says that Petra Olsdatter was seventeen years old when she died.”

“That is what she told my cousin.”

“But if you look in the court records, you’ll see that she was born in 1880.”

André took a closer look. “Yes, indeed! So she must have been nineteen. She was dying, so she might have spoken indistinctly. Or might not have been quite clear in the head. Yes, I agree with you. I thought that it was a bit much that a seventeen-year-old could already have two children. Thank you for your observation. There was something else I noticed in the records: at the hearing, somebody, a relative perhaps, spoke of a missing locket that had belonged to Petra. They couldn’t find it anywhere.”

“That’s interesting,” the lady said. “Although a locket can easily get lost.”

“What a shame. It might tell us a thing or two,” said André. He realized that he had said “us”. He blushed and asked the lady for the address of the orphanage, which she gave him. Then he thanked her for her assistance and left the building.

He had time to pay another visit that day, so of course he decided to visit the home of Petra’s parents in Bakklandet.

As he walked through the streets of Trondheim and crossed the bridge – he wasn’t sure that his car would be able to get through these narrow streets – he remembered that Silje had been here many centuries ago: lonely, scared, frozen and destitute. At the same time, Charlotte Meiden had been out with her newborn baby. On that very night, Silje had also met Tengel and the child Sol and Heming the Bailiffkiller.

What a strange night that must have been!

It was the night of destiny, when the foundation was laid for the new family that fought for good instead of playing Tengel the Evil’s game. André wondered what Silje and the others would have thought if they had known what had happened to the Ice People since then. All their varying fates ...

Tengel the Good knew ...

But it was many years since he had last appeared. Since Lucifer had entered the picture, the ancestors had passed on the responsibility for the Ice People to the descendants of the black angel: Marco, and now Imre.

Marco had said that they collaborated with the ancestors. Tengel the Good knew about everything that was going on. André felt a twinge of pain in his heart at the thought of Marco, because he missed him dreadfully. But Marco wouldn’t show himself anymore. He must be pretty old by now, surely? Imre, who was fair and gentle, had taken his place. He had appeared only once at Linden Avenue, standing in the doorway one frosty morning with the infant Christa in his arms. Since then, they hadn’t heard from him.

But then, life flowed quietly for them all now. They didn’t need supernatural assistance.

André had arrived in a miserable slum, and he winced. Was this where Petra’s father ...? It wasn’t. As he walked on, small but fairly well-kept houses replaced the hovels, and he found the right address. He took a few deep breaths before he lifted the door knocker.

He could hear children playing in the courtyard inside. The game abated. Then eager feet came running and the gate was opened with some difficulty.

Four or five children stared at him. They weren’t terribly clean, and their noses needed wiping.

“Hello,” said André politely. “Does a man by the name of Ola or Ole live here?”

Their stares became more intense.

A door into the courtyard opened and a woman’s voice shouted: “What is it, children? Who’s there?”

Hesitantly, they let André in through the gate and he made his way to the door where the woman was standing, with her hair sticking up and a pail in her hand.

André repeated his request.

“Ola? There’s no Ola here,” the woman said dismissively. “Or Ole.”

“Has anybody by that name ever lived here?”

The woman wrinkled her brow. She was remarkably skinny and poor, but made it a point of honour to keep the place looking nice and clean. “Yes,” she replied, matter-of-factly, “but it was a long time ago.”

André did some swift arithmetic. When might Petra’s father have thrown her out? In 1899 she was seventeen – no, nineteen. If she had her first child a few years before that? Well, for heaven’s sake, what had they been thinking? Surely a seventeen-year-old couldn’t have had two children by then. Of course, it was possible but then she would have been fifteen the first time. And the child would have been conceived when she was fourteen. No, that sounded grotesque. Of course, Petra was nineteen when she and Vanja met one another!

Anyway, now he had arrived at a year. “That must have been around 1897,” he said.

The woman pondered. “Yes, that makes sense. A man by the name of Ole Knudsen lived here, but that was before my time,”

“Where ... is he now?”

“He’s dead.”

Damn, André thought, but aloud he said: “What about his family?”

“I don’t know. Wait a moment.”

In a shrill voice, she shouted into the house: “Mother, did Ole Knudsen have any relatives?”

An indistinct, squeaky reply came from inside the house. The woman in the doorway translated: “My mother says he had a daughter. But she got into trouble.”

Well, thank you, thought André, I know that. “Was she an only child?”

A new question into the house. The reply came promptly. The woman turned to André: “Mother says that he had a son as well, but he died of strangles.”

André thought that was something only horses got.

“As a grown-up?”

There was yet another exchange between the door and the inner room. “No the poor boy was probably only sixteen at the time.”

André didn’t dare to ask whether Ole Knudsen had any siblings. His informant seemed to be getting slightly annoyed. Instead he fished out his purse and gave her some money for the “invaluable information”, as he called it. Now he could ask more questions because now the woman appeared more willing to cooperate. He had something to work on, so he asked permission to come back again if he needed to know more. She said he was welcome to do so.

The children, who had been hanging around him, ran as fast as they could to be the first to open the gate and let him out. He found some small coins and gave one to each of them. He was bound to be popular in that yard.

That was all he had time for that day. He went back to his hotel, working out a list of what he had found out and what he ought to do the following day.

Nette Mikalsrud unlocked the door to her small apartment. As usual, she registered the old-fashioned atmosphere inside. This was where she and her mother had lived for the past thirty years. Now her mother was dead and Nette lived there on her own.

She was actually called Antonette, but she detested that name. So when people had begun to call her Nette when she was a child, she had accepted the nickname gratefully.

She had been a beautiful and much-loved child. But when her father died, her mother had clung on to her only daughter, killing all her romantic dreams about young men going down on their knees to her.

The family’s financial situation had been dire. Something had to be done, and Nette resolutely applied for a lowly job as a messenger with the local council. Of course, her mother had been almost hysterical: young women from good families didn’t work, and definitely not in such a miserable job. What was the mother to do while Nette was out all day?

The housework, the girl had replied bluntly. Somebody had to do it. But it had always been Nette who did that, hadn’t it? Well, perhaps her mother would like to earn the money and get a job herself? Oh, no, the older woman was shocked. What a thought!

As time went by, things began to work out for the two women. Nette was efficient and clever, and there were opportunities for a young woman to do more important things than running errands and making coffee for the council staff. She got a better job, and her mother was thrilled with the money she earned.

The years passed. Nette was promoted. Then her mother died. That was when Nette discovered that her life was frighteningly empty.

Deep in thought, she took off her big hat with the bunch of artificial cherries on the brim. For the first time in a long while, she looked at herself in the mirror.

She looked shockingly old, with that lorgnette dangling on a string! It would be better if she kept it in a case in her pocket. And her hair ...? She loosened it carefully with both hands. She touched her high, stiff collar and held it a little away from her throat.

Miserable! What she saw in the mirror was a sad, middle-aged, totally charmless woman. She rapidly set about preparing food and dusting the tables and shelves in her small, lonely apartment.