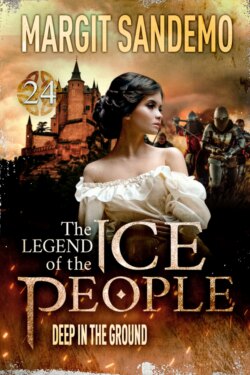

Читать книгу The Ice People 24 - Deep in the Ground - Margit Sandemo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

But she couldn’t stay standing in this bare room for all eternity! Hesitantly, she went outside again and this time she received help. The woman in the nearest house signalled to her that she should go around the corner.

There was nothing there but a blank wall, but Anna Maria continued around the next corner and reached the other long side, where she found what was clearly the only entrance to the building. She walked in and saw that there was actually a sign that said “Mine Office”.

Anna Maria knocked and entered.

A man was sitting behind a writing desk that was so impressive that it seemed almost out of place in these poor surroundings. The room itself wasn’t much to write home about since it was built in a barracks. But this man, who seemed very worried at the moment, had clearly tried to do something about the arrangement. It wasn’t his fault that the attempt had failed!

It was Adrian Brandt! It certainly was, even though Anna Maria could barely recognize him at first. Six years filled with exaggerated, romantic notions of a person can completely distort one’s memory of them. But here he was – in reality and six years older than when she had last seen him.

He was still young, of course – that wasn’t where the transformation lay. Yet she did have difficulty recognizing him.

The ash-blond hair, the sad eyes as blue as the summer sky, the face – completely ordinary yet still attractive due to those eyes and an overall impression that was very appealing – it was all there, yet something was different.

When he caught sight of her the worried wrinkles in his brow evened out immediately and he became more like the noble, cheerful knight she remembered from her early youth. He got to his feet.

Anna Maria had been anxious about meeting him: she could feel that now. And the blunder of getting lost and then accidentally hearing that her presence wasn’t welcome had made her nervous. But Adrian Brandt looked very friendly, which put her mind at rest. Friendly – and surprised?

He approached her, his hand outstretched. Anna Maria accepted it. It was warm and firm. Before she could stop herself, she curtseyed to him. She was no more mature than that.

“Well, so here is Birgitta’s niece,” he said. “Little Anna Maria, yes, we’ve met before, haven’t we? You are very welcome! You are younger than I had expected, but still it will all work out: you have excellent exam results and fine references. Well, I am Adrian Brandt, as you probably remember, and I run this little ... pastime of mine.”

That was quite a phrase to use about a whole mining operation! It was clear that he felt it was beneath him.

But his laughter when he said it – slightly proud and slightly shy – was disarming. Practically in the same breath he continued, “I’m only here every now and then to make sure that things are running smoothly. I was just on my way back to town but waited to bid you welcome upon your arrival. My clerk will see to you. Nilsson!” he shouted.

Anna Maria grew tense. Was he the one who didn’t want a young lady on the premises? The one named Kol or something like that ...

“The Director called!” answered a servile voice. An overgrown cherub dressed in black clerk’s clothes and long white oversleeves appeared. No, she thought. It certainly wasn’t him.

He had made an attempt to part his hair down the middle by combing and straightening it. But he had failed, and tufts of hair stuck out here and there. He had probably tried to model it on Adrian Brandt’s modern hairstyle, with small curls pulled forward at the temples. Nilsson’s curls had resisted, so the result was rather comical. Both men wore the high, stiff, white collar nicknamed the “father killer”. It must be very uncomfortable to wear, Anna Maria thought.

“Nilsson,” said Adrian Brandt in his quick, somewhat hectic tone. “You’ll show Anna Maria Olsdatter the premises, won’t you? I must be off now.”

Nilsson bowed and scraped, making his tight waistcoat creak at the seams. He quickly brushed a few cake crumbs from his clothes. “Of course, Mr Director, of course! You can count on me, Sir!”

Adrian Brandt bade her farewell. “Nilsson will take care of everything, just ask him if there is anything you need help with. I’ll return at the end of the week together with my family – my mother and my two sisters. They like to get some country air every so often.”

Then he rushed out.

She felt somewhat brushed aside. He could have given her a warmer welcome, she thought, but perhaps she hadn’t made much of an impression on him six years ago: at least it hadn’t been as great as the impression he had made on her as a child.

“Director Brandt has many irons in the fire,” Nilsson said, smiling, his round cheeks looking as though they were ready to explode. “Of course, he leaves most of it to me.”

His eyes glided lizard-like and quick as lightning over her as his tongue quickly licked his childish pout.

“I would like to be shown to my room,” she said in as friendly a voice as she could muster. “And I would like to know where the school is.”

“Yes, of course. Follow me.”

He took a bunch of keys from the writing desk, rattling them importantly.

“Can the young Miss really teach?” he asked in his oily voice. “You don’t look much more than a schoolgirl yourself.”

Anna Marie guessed him to be about thirty-five to forty years old, an overripe church angel, who consoled himself with too much cake and other unhealthy food, though how he was able to afford it on a meagre clerk’s salary was unfathomable. But at least he seemed harmless.

That impression was one that would later change.

They went outside. He was actually carrying her travelling bag, which she hadn’t expected him to do, and she told him briefly about her education as he locked up. Then they walked around the corner of the building.

“Where will I live?”

“At Klara Andersdatter’s, which is the third house from here. She is allowed to go on living in Ytterheden because she does the men’s laundry and washes their floors. Her husband, who used to work here, ran off with the Clump’s wife, so she doesn’t really have the right to remain here. The Clump had to move back to the barracks. But perhaps we should look at the schoolroom while we are here ...”

To Anna Maria’s consternation, Nilsson headed for the empty storeroom she had entered earlier as he went on chatting away all the while. “But the young Miss must beware of the men around here. Their manners aren’t always like ours. They are uncultivated plebeians.”

“I’ll be careful.”

“We had been expecting a somewhat older person.”

The question she then posed to him came rather spontaneously. “Perhaps not everyone is pleased to have a female teacher here? Perhaps they would have preferred a man?”

“Oh, it’s only Kol, that barbarian, who’s been complaining about it. Don’t worry about him.”

“Kol?”

“Yes, the foreman. He was the one who insisted that the children here have some schooling. It’s like casting pearls before swine, if you ask me.”

He opened the door to the ugly, echoing, empty room she had only recently been into. “Yes, well, this is the classroom. Kol has promised to have it ready with benches and a lectern by Wednesday. Then the young Miss can begin teaching.”

She looked around in dismay. She would never be able to create a good atmosphere in here, and that was of the utmost importance in a classroom, she believed. Everything seemed dilapidated, neglected and cold.

“What will we do in the winter?” she asked meekly. “About heating it, I mean?”

“That will be taken care of,” he promised.

“Kol? Is that his first name or his surname?”

“He actually has a completely different name but it was too hard to pronounce. He is of Walloon descent, from the Belgian blacksmiths that came to Sweden in the 1600s.”

Anna Maria nodded. She had heard about them.

“Didn’t they keep to themselves for a long time?”

“Yes, that’s why our foreman has a foreign name. Guillaume Simon, I think it is, but simple miners can’t pronounce that. They aren’t educated like us. So he’s just known as Kol Simon or usually just plain Kol – which comes from the word ‘coal’, because he’s so black.”

“Black – how?”

“His hair and eyes. He’s also hard as nails. He gets dangerous when he’s angry. But he’s good at what he does.”

Yes, hard as nails, she could believe that all right: she had heard the tone of his voice. Already once too often, she thought.

“Yes,” she said despondently, as she cast a last glance around the bleak room. “Shall we go to my lodgings, then?”

Nilsson once again took her bag chivalrously as he locked the door. “It’s heavy,” he commented.

“Books,” she said laconically.

He made no comment.

As they walked down the autumn-dry road – or street, if it was possible to use that term to describe it – Nilsson continued to chatter.

“When the director isn’t here I am the one who is responsible for everything, of course ... here at the first house is where Gustav, the blacksmith, lives. All his children have consumption ... And I believe that the director is satisfied with my work. He is going through a very difficult time so it is understandable that he is leaving much of the work to me.”

Anna Maria nodded. “He has just become a widower, I know.”

“A terrible tragedy,” Nilsson said unctuously. “And such an adorable wife! She died in childbirth. Of course, it’s not uncommon, but she was a pure angel! This next house is where Seved lives. His wife receives visitors whenever he’s in the mines. No one, least of all herself, knows who is the father of her youngest child. Well! Here we are! And here is Klara, with whom you will be staying. Hello, Klara, this is your new lodger.”

The bitter, haggard woman at the door said nothing. She just gave Anna Maria a sour nod and gestured her to come inside with a movement of her hand. “Well then, I’ll return to the office,” Nilsson said. “I have much to see to.”

Klara mumbled something about a “gossipmonger in trousers” as she led Anna Maria into the hall. It was gloomy and the paint on the walls was peeling, but everything smelled clean. Klara, a woman of uncertain age, opened a door.

“Here is the room, if the young lady can make do with this,” she muttered aggressively.

It could have been worse. The room was modestly furnished with a bed, a chair and a washstand. There was a homemade chest of drawers over which hung a quote from the Bible. And there was a flower on the windowsill.

Anna Maria turned to her, smiling shyly. “It’s very nice. You run a very clean household, Mrs Andersdatter. Everything is so nice!”

“I do my best,” Klara said without smiling.

“You can’t do more than that,” said Anna Maria with a smile.

“No, but every so often even that isn’t enough. Will Miss be eating with us or would she prefer to see to her meals herself?”

Anna Maria hesitated. “If it’s not too much trouble, I would like to have a meal when I come home from school. The rest, breakfast and dinner, I will see to myself.”

Klara nodded firmly. “That will cost you a little extra. For the meal, I mean. The mining business is taking care of the rent.”

“All right. Well, what shall we say ...?” Anna Maria suggested a sum that made Klara raise her eyebrows. The girl clearly didn’t know much about the value of money – at least she didn’t know what it meant to these Swedish workers. But the suggestion was far from unwelcome! For that amount, the hostess offered a few extras, such as a cup of coffee on Sunday and every now and then in the evening. Anna Maria accepted the offer.

“Do you have children, Klara?”

“Four in all. But only the oldest one will be attending school. The others are too young.”

“I look forward to meeting them!” said Anna Maria with a radiant smile.

“If Miss would like to unpack now, I will leave you. Afterwards you may come into the kitchen and I will show you where everything is and I’ll have some food ready for you. You must be hungry, Miss?”

“Yes, I’ve been terribly nervous all day about arriving in a new place and meeting new people.”

“You are very young, Miss.

“Nineteen. But I have been alone for a long time now so I’m sure I’ll manage.”

“You are also good-looking. I’m sure the young men of the village will be queuing up here when winter comes.”

“Oh?” Anna Maria cried out in surprise. “No, no man has ever given me much attention.”

Klara looked at her suspiciously to see if she really was so simple-minded or was just putting on airs. But Anna Maria looked perfectly innocent.

Then the hostess went to prepare some food and Anna Maria began to slowly unpack her belongings. The jam jar was intact, thank goodness! She carefully placed her fine underwear in the coarsely carved chest of drawers, which had an acrid smell of lye. She arranged her few personal items on the chest to create a little atmosphere in the room and make it feel more homely.

The little embroidered tablecloth, the brush and comb of real silver that she had received on the day of her confirmation, the inlaid sewing box with the red silk lining: all of it reminded her of days gone by and all the loved ones she had lost ...

What was left of Anna Maria’s willpower ran out. There, in that strange, spartan room, she collapsed on the edge of the bed as she looked absently at the miniature portraits of her parents, Sara and Ola, together in a decorative wooden frame.

The old pain returned. The one she had felt for many months now, even though the journey and all the tension connected with it had displaced that bad feeling for some days.

Her sense of loneliness consumed her. The bottomless loneliness that comes from within and that has nothing to do with whether there are people around one or not.

“God,” she whispered, “Dear God, how am I to make it better? It’s too late now.”

And what am I doing here? At the edge of the sea, in this remote corner of the world? Did I think I could escape my thoughts here?

How stupid! How shortsighted. You can’t escape yourself!

Disheartened and powerless, she looked at the bare walls of a stranger’s house, the worn floor with the clumsily made rag rug, old and well-used furniture – used by others. Where were her own things? Why had she left her beloved home?

But she knew perfectly well why. She couldn’t stand just existing at home, walking restlessly from one empty room to another, constantly being reminded of her parents. Her thoughts would just have driven her mad. She had had to get out and feel that she was needed in some way.

So as to numb herself? No, she mustn’t think that way any longer.

Adrian Brandt!

What a bad idea it had been to come here! Imagine that she had actually thought she meant anything to him! And he could barely remember her!

She simply had to look to the future now! Behind her lay all the gloominess and all the things she couldn’t overcome that she, in her naivety, had thought she could escape.

But that was, of course, impossible.

Miraculously, the schoolroom was ready on Wednesday. That was something she hadn’t expected. But when she stood looking around the room in the early morning she couldn’t escape the depressed mood she felt inside. This wasn’t exactly what she had been hoping for.

When they had referred to benches they had meant it quite literally. There were three coarsely carved long benches in the room, so the children would have to sit in rows with their books on their laps as they worked. As the teacher she had been given a worn chair to sit on and a wobbly desk. But there was one good thing placed right behind where she was standing: they had actually managed to acquire a real blackboard with a slate pencil and everything!

But that was all there was.

Well, there was also the stove, the miracle of miracles: an old, rusty iron stove that had been installed in the corner with a big pipe that, in the ugliest way, bent upwards until it reached and entered the wall behind it. But it certainly wasn’t a fire hazard: the area around it had been properly mortared. Drops of mortar had solidified here and there on the floor and wall, and no one had bothered to remove them.

Still, it was an impressive piece of work to accomplish in a matter of just two days!

She herself had spent her Tuesday going through the schoolwork, planning and preparing for the first day. She had spoken to the clerk, Nilsson, and had been granted permission to order the materials that she and the children would need. Within limits, of course!

She still didn’t know anything about the students – what levels they were at and which textbooks they had.

The wind had started blowing. The muggy autumn rain was swirling about her when she walked home to eat breakfast before the classes began.

She and Klara had had a talk on Tuesday evening after the children had gone to bed. The hostess expressed an aggressive bewilderment at the many fine things the young lady owned. A silver brush and paintings, and such fine clothes! Was it really necessary for the young Miss to take up such a dreadful occupation?

Then Anna Maria told her about her situation. About the death of her father and how she had had to take care of her mother for two years. And then how she was suddenly alone in life. And how she had had the choice to live with relatives and not lift a finger, or repay the kindness of her parents in using the good education they had given her and putting it to use for others.

Klara had pondered this and thought it sounded relatively sound.

“I couldn’t imagine anything better than walking around in fine clothes and being waited on. But ... it would probably become boring in the end, yes,” she admitted. “And a woman who is alone must work for a living,” she said, nodding. “But I’m sure the young Miss is still rich?”

Anna Maria sighed. “In a way. When I inherit my grandmother’s estate I will be wealthy,” she said and grimaced. “But I love Grandmother Ingela and want her to have a long life. I don’t look forward to having money because of her death.”

That was very noble of her, Klara thought.

“And what about yourself?” Anna Maria asked kindly. “How do you manage to keep this house so neat all alone with four children and heavy work on top of everything?”

“The Clump helps me with the heavy work,” Klara answered.

“The Clump ...? Wait, I’ve heard that name before.”

“Probably from the gossipmonger Nilsson. The Clump is my brother, you see. He was given that name because he has a bad leg. He suffered a lot as a boy because of it – well, you, Miss, know what children can be like. Who says they are little angels? Not me, I saw the way they bullied my little brother.”

Suddenly Anna Maria remembered what Nilsson had said: “Klara’s husband ran away with the Clump’s wife. Klara is allowed to remain here because she does the men’s laundry and washes the floors. The Clump had to move back into the barracks.”

“Now I remember what the clerk said,” Anna Maria nodded. “But I didn’t know that the Clump was your brother.”

“Oh, yes,” Klara said dryly. “We siblings were the leftovers. Worthless: no one wanted us. It didn’t bother me so much because my husband wasn’t nice to me anyway. But it was a shame for my little brother. He’s suffered enough in life.”

“You always suffer more on the part of others than for yourself,” Anna Maria said. “I think the most difficult thing for parents must be to see their child neglected or hurt. And I suppose the same is true of an older sister who has tender feelings for a little brother who is having a hard time.”

“The young lady knows too much for her age,” Klara muttered, but she didn’t sound angry.

“I know a little bit about pain,” Anna Maria said quietly.

“Yes, of course. You lost your own parents.”

A painful twinge rushed through Anna Maria. “Yes, that as well,” she whispered almost to herself. “But you have such wonderful children, I look forward to having Greta in my class.”

Something that resembled joy and pride crossed Klara’s haggard face. Anna Maria sensed that the two women would become good friends eventually, when all the barriers had been pulled down.

As the hour struck ten she was back in the classroom. And the children had now arrived.

They jumped up from their benches when she entered. They curtseyed and bowed low, their hair wet-combed and wearing their best clothes: homespun, black and clumsy. Only a few of them wore shoes. Anna Maria could easily see that this was a poverty-stricken community. The girls’ dresses seemed to be made from recycled materials that were already worn out. And the children’s faces showed that they were living on the verge of starvation and had already had their share of bad experiences.

How exactly did Adrian Brandt provide for his employees?

The special, pervasive smell of worn clothes that was so typical of all classrooms was evident in here and the class hadn’t even begun yet!

There weren’t that many children. Klara had already told her that there were only five houses with young families living in them, plus a few more out on the moor.

She counted them. There were nine children, whose ages seemed to range from seven to seventeen. Six girls and three boys.

She started by greeting them, and she was probably just as shy and insecure as they were. She told them her name and said that they should call her “Miss”. Then she asked for their names.

They practically whispered their names to her, very shyly. She already knew Klara’s daughter, Greta, a scrawny little ten-year-old who had been given permission to come into Anna Maria’s room the previous day and admire all her fine belongings on the dresser. She was now a devoted worshipper of Anna Maria. Then there were the two children of Gustav, the blacksmith, who lived in the first house. Yes, Nilsson had been right, they seemed to be suffering from consumption and had bad coughs. They were a boy and a girl. Then there was a big lout by the name of Bengt-Edvard. And the oldest girl, whose same was Anna.

“Then we have almost the same name,” Anna Maria said, and the girl blushed deeply.

And then there was a miserable little boy dressed in thin clothes and covered in bruises. His name was Egon. Goodness gracious, Anna Maria thought. Oh, heavens! She asked where he lived.

“Out on the moor,” he whispered, whereupon he sneezed violently.

He could use a handkerchief, Anna Maria thought, somewhat desperately. But she didn’t feel like sacrificing her own.

The last three were girls. One of them was Seved’s daughter.

Seved? She searched her memory. Oh, yes, he was the one who lived in the second house and whose wife received visitors whenever he went down the mine. No one knew who the youngest child’s father was.

Ugh, Nilsson with all his miserable gossip! She wished she hadn’t heard it because it tainted her view of the children and the village.

The only one who came from the moor was little Egon.

She had wondered why it was only young families who were allowed to live in the houses. The Clump had lived there and had had to move back to the miners’ barracks after his wife ran off. Klara had told her that he had a little daughter, but the wife had taken her with her when she left. The Clump had grieved most over the loss of the child. After he had moved back to the barracks another family had moved into the house. They were the parents of the lout, Bengt-Edvard, and his two sisters. They all lived in the fifth house, the farthest off.

It seemed that there was a strict rule here: no children, no house. Nothing more than a bed in the barracks, which Anna Maria guessed must be in a bad state. It looked really dilapidated and cramped.

But the houses were hardly palaces. Klara’s was probably the best kept. Perhaps that was why Anna Maria had been put up there. On top of that, the houses were crowded with children under school age.

As soon as the children were big enough, they were sent into the mine. That was why, to begin with, Anna Maria didn’t understand why a big boy like Bengt-Edvard had been allowed to come to school.

It became apparent that none of them could read or write. She would have to start from scratch, for which she was actually thankful. It made things easier for her because she didn’t have to teach various levels at once. The children could be kept in one group.

They had never had books before.

“Good,” Anna Maria said, trying to sound cheerful. “Then, until we get more materials, we’ll just do this: I have a small slate and we’ll pass it round the class. And then we can use the big blackboard. Isn’t it cold though? It was so damp today. Are you cold?” she asked as she looked at shabby little Egon and the two coughing siblings. “I’m going to try to light the stove if there’s anything I can use to do it.”

Then Bengt-Edvard’s coarse voice could be heard, sounding as though it was cracking. “You can’t light the stove, Miss. It’s not finished yet.”

Anna Maria looked with surprise from him to the stove, and not until then did she realize that the pipe was not connected to the black monstrosity.

“But ...” she began.

“We didn’t get it done in time,” Bengt-Edvard explained, slightly ashamed. “We worked all night but we didn’t finish it.”

“I think you’ve done a tremendous piece of work,” Anna Maria assured him warmly. “Did you help with it?”

“Yes, Kol ... the foreman, I mean, and Father and some other men and me.”

She nodded. She didn’t want to ask him why he was attending school instead of working in the mine. He didn’t seem to be very bright but you never knew, of course.

And that was when Anna Maria Olsdatter began to teach her first lesson. Fumbling and insecure to start with, but the children were so obedient ... and, well, suppressed actually, so she didn’t have any problem keeping discipline.

But she had an unpleasant feeling inside, a nagging sense of despair, a need to do something for these poverty-stricken children, to become their friend and confidante, to really help them.

Especially little Egon in his thin rags, which were probably considered to be his best clothes.

Anna Maria observed him secretly now and then. His face had probably been washed clean before he left for school that day. At least she hoped so. But Egon looked as though he was the kind of boy who attracted dirt. His mousy hair stuck out on all sides, stiff with grease. Soil and dust and snot and tears had left streaky marks on his frightened face, and the much too large homespun trousers flapped around his frail body. They had a tear at the knee and his bony hands were blue with the cold.

Gustav’s two children needed medical attention – that was quite clear. They also risked infecting the other children if they hadn’t already done so. Even fragile little Egon, perhaps?

When all the children had learned the capital letter A and had written their first name on the board by following the teacher’s instructions, she felt that it was time for a song. Since they all knew the psalm with the words “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil,” that was what they sang. The children probably knew it from having attended frequent funerals.

And that was when Bengt-Edvard’s true talent shone through! He had moaned and groaned over his long name when he had to write it on the board, and had wished that his name was Egon instead. Now he was singing with confidence and intensity, and had a voice like a future opera singer!

After the last verse Anna Maria looked at him in awe. “Do your parents know what a wonderful voice you have?”

He blushed with pride. “Yes, they want me to go to school so that I can manage better when I am out in the world. Sign contracts and that sort of thing so that I don’t get cheated. I’m going to be one of those people who goes on tours and earns a lot of money at markets.”

More than just at markets, Anna Maria thought, but she didn’t want to question his parents’ authority in the presence of the other children.

“Then we’ll try to teach you everything you need to know,” she said kindly. “And that’s all for today, children. It’s the first day and it’s been so cold in here. I’ll see you again on Friday at nine o’clock. You’ll only be attending school three days a week, you know: Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. I will try to acquire slates for you all, and counting frames because you are also going to learn arithmetic.”

Books won’t be relevant for a long, long time, she added to herself.

“Will it be expensive?” a girl asked anxiously.

“It won’t cost you anything,” Anna Maria answered, somewhat thoughtlessly.

When they left Bengt-Edvard stayed behind. “If you ever encounter problems, just let me know,” he said.

“Thank you, Bengt-Edvard, but what kind of problems would they be?”

He looked around and, lowering his voice to a subdued mumble, said, “With the miners. They are talking about spooning with the new young Miss.”

Anna Maria swallowed. “Thank you for the warning, Bengt-Edvard. I will be sure to be careful.”

Since the first day at school had been short, she walked directly over to the mine office to order the materials the children needed.

Nilsson gave her a disapproving look, “Is it really necessary for them all to have books?” he asked, putting a piece of liquorice in his pocket and wiping something brownish from his mouth.

“A small slate each is the very least we can give them,” she said with a hint of sternness in her voice. “And counting frames. And slate pencils. I could have asked for much more, but this is the very least. Otherwise I won’t be able to teach them!”

He sighed. “I’m going to catch it from the director for this. And it’s all because of that hooligan, Kol.”

“The foreman? He must be a very cultivated man since he is arranging all this for the children.”

“Cultivated? Him? He’s the most uncultivated of them all. He just has some silly idea about giving others the opportunity to have the things he never had. Ridiculous!”

“But all children in Sweden have a right to go to school ...”

“Not miners’ children. You can’t teach them anything,” Nilsson answered in disgust. “Believe me, Miss Olsdatter, you are wasting your time! You shouldn’t put ideas into the minds of those poor creatures. It isn’t healthy to have an enlightened working class; it doesn’t make any sense!”

Perhaps the competition would make a person nervous, Anna Maria thought maliciously. She didn’t bother to answer him. His whole reasoning was too stupid. She just became even more determined to give the children what they had a right to: a good education.

Now she was happy that she had come here! That she had come to know little, helpless Egon. And Bengt-Edvard with the great voice. The sick children. And Klara with all her strength.

Nilsson could go to blazes for all she cared!

The desire for something sweet overwhelmed the little man and he dug out the liquorice from his pocket.

But he promised with a sigh to make sure that the materials arrived as soon as possible.