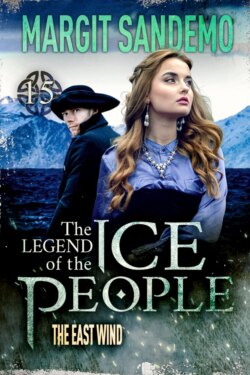

Читать книгу The Ice People 15 - The East Wind - Margit Sandemo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

A great surprise awaited them in Tobolsk.

Apparently they weren’t the first Swedes to arrive there. The Russians had made previous expeditions to the Swedish Baltic provinces and Finland and had taken prisoners there too, including men, women and children. For King Karl XII’s soldiers, who had endured harsh military life for so long, it was strange meeting women again, women whom you could talk to and associate with without disgrace.

They also soon discovered that the Swedish prisoners in Tobolsk had managed to create their own community in the city. There were now about fifteen hundred Swedes there, including the eight hundred newly arrived soldiers.

In some ways life was better for them in Tobolsk than it had been in the other places they had been sent to. Except for the times when the Russian officers got drunk and decided to go out and “fix those heathen Swedish pigs”. Things could get pretty wild then. The prisoners were constantly under close guard, so escape was impossible. If there was the least sign suggesting the possibility of a conspiracy or revolt, those involved would be sent even further eastward, where they would eventually disappear for good in the never-ending terrain of Siberia.

But the Swedes had to manage one way or another, so they started teaching each other their craft skills, and the things they produced were soon in high demand. They learned to dress like Russian farmers, since this not only proved to be a necessity in the harsh climate but also meant they avoided standing out from the crowd too much. It gave them more opportunities to move around safely. Some of them started producing distilled alcohol, but this wasn’t a popular move because there was only one person who had the exclusive rights to the profits made from distilling alcohol, and that was the tsar himself.

Some of the Swedes married Russian women and wanted to remain where they were. But most of them had a constant longing to return home. Home! Home to Sweden or to Karl XII’s army so that they could assist their king.

He must have had a strange personality. Despite the fact that he had managed to bring his country down with his numerous wars, despite the fact that he was never at home in his kingdom, he kept his status as a hero without peer among his soldiers and the generals of the time, and also among his enemies. Perhaps it was due to his ascetic lifestyle, strong will and ability to keep his word. He was intelligent and civilized, but when he made one of his rare public appearances he was the most taciturn of people. Particularly about himself. On a personal level he was, and remained, a riddle. But to the soldiers he was like a god. He always shared in their fortune and he never allowed himself any privileges that they didn’t have access to. He was stubborn and obstinate with his equals, however: everyone was expected to yield to the ideas that came out of his sharp brain and his well-devised war strategy.

So now, although half his army had been captured in enemy territory under extremely difficult conditions, their only thought was that they wanted to get home again so that they could continue fighting with their king. Incomprehensible!

Yet there were still deserters. Most of them had made their escape during the march to Moscow and then in the capital city itself. But there were also some who managed to escape imprisonment in Siberia. Those who were left behind would often think about the ones who had managed to disappear, but they knew nothing of their fate. Getting back to Sweden or reaching Karl XII’s army weren’t exactly short trips.

The young Vendel Grip was eager to learn a craft. He could choose forging, pottery, or furniture-making, he could become a saddler, engraver or goldsmith, he could sew beautiful horse cloths or cut precious stones. As bright as he was, he quickly learned the art of preparing hides – with saddlery in mind – but he soon discovered that he found it more enjoyable to decorate the hides with ornamentation. He became so good at it that he was given the task of training twelve other soldiers of limited means every Sunday. Many officers who wanted to learn a craft attended.

Vendel was doing well, not least financially. He sold his beautiful hides or traded them for useful goods from the people in the town or from farmers who came in from the surrounding countryside on market days. Needless to say, he didn’t make huge sums of money, but what he earned he saved in the house he shared with the other soldiers of King Karl XII.

He didn’t see Corfitz Beck all that much any more. Beck had started associating with one of the families that had arrived there from the Baltic provinces. The head of the family was Lieutenant-Colonel Claes Skogh: he was the father and also a seasoned soldier and a man of authority.

Vendel had been invited there once. The Skogh family had a daughter, Maria, who was exactly the same age as Vendel. She was sweet – very sweet – and Vendel’s romantic heart had begun to grow warm. During dinner he sat next to her and he had never been so close to such a feminine creature before. Suddenly his hands seemed incredibly big and clumsy, constantly in danger of knocking over his glass. His tongue refused to obey him and he was practically stammering, and it was as though all the intelligent words he was accustomed to using simply vanished all at once. Where did all these empty phrases come from that he couldn’t stop saying?

But it seemed as if no one noticed his agony. Maria smiled sweetly and a little absent-mindedly and turned just as often to Corfitz Beck, who sat on her other side. But every time she looked at Vendel he got the feeling that something within him had died a little. It was his childhood that died. He felt that he was on his way to becoming a grown-up. And he was twenty years old – it was about time!

The Skogh family lived in one of the finer houses that had been allotted to the Swedish prisoners. Of course, it wasn’t much bigger than a shed and it was hard to say exactly how many families lived there. They had tried to give the house a certain style, as well as they could in their modest circumstances. But for Vendel it was like visiting a real home after all those harsh years in foreign countries.

After the visit he returned to the miserable hovel he shared with the other soldiers. The buran, or the purga, as it was called in Siberia, blew savagely through the streets, heralding a rise in temperature. It was much needed because it had been cold for a long time. Vendel should have been freezing in his plain and simple clothes, but he wasn’t. It felt as though he was walking on air.

As soon as he got home he went to the workshop. There was a small leather purse he had started work on. Initially he had intended to sell it but he now changed his mind. Maria was to have it, she and no one else. And he would make a pattern so exceptionally fine that nothing like it would ever have been seen before.

Vendel worked all night and fell asleep at the workbench. The next day he was supposed to be helping with the construction of a tower in the city, which was already known as the “Swedish Tower” and which would retain that name through the following centuries after the Swedish soldiers of Karl XII who wore themselves out building it.

As they had expected, the weather changed: the purga had delivered some heat in the air but the wind continued to blow just as forcefully. In this temperature building work could continue easily, but Vendel had no time for that. He coughed horribly when the guards came to fetch them and asked if he might stay at home, just for that day. He must have looked very pale after staying up all night working, because the guards let him stay.

That meant that he could continue working on the leather purse. The work took a whole week, but when it was finished it was as beautiful as you could imagine. It had a relief pattern in azure and yellow and an intricate closing mechanism.

Every evening Vendel would casually stroll past the Skogh family’s house. Once he ran into her as she rushed back home, her hands inside a fur muff. “I have to make her a muff,” was his immediate thought.

He lifted his hat and greeted her respectfully. Maria gave him an uncomprehending look, then she recognized him and stopped. She held out her little hand and Vendel had a hard time letting go of it, but he managed to stay within the limits of proper behaviour.

“It was nice talking to you the other night, Miss Maria,” he said politely, because that was what he had practised. But then he was suddenly at a loss for words. “Uhm ... it’s ... uhm ... nice weather today.”

The weather wasn’t nice, but she agreed with him because she didn’t know what to say either.

They were both perplexed for a moment as they stood there, but then she appeared to want to move on.

“Well, I’d better be going,” she murmured dimly.

“Help me, good gods, make her stay,” Vendel moaned inwardly, but the gods were not being very cooperative.

“S-say hello to your mother and father,” he stammered perplexedly, and she nodded and disappeared.

And then there was the purse. How on earth was he going to deliver it to her in a way that would seem suitable? In such a way so that it seemed the kind of gift you might give to the daughter of a family you knew but at the same time so that she understood the love that lay behind it? Without thinking about it, he had probably been hoping to be invited there again, and then it would have been easy to say casually, “Speaking of my work, I have a small thing with me I’ve been working on in my spare time, just for fun. Perhaps Miss Maria would be interested in having it?”

No one could take offence at something like that. And she would be ecstatic and thank him with radiant eyes and then she’d think of him every time she took out her purse to buy something.

But he was not invited back to the Skogh household again. Spring passed, the wind from the taiga forest grew increasingly mild, the migrant birds arrived and the few brightly coloured flowers that grew in the fields began to shoot up outside the city boundary. But Vendel never saw them because he never left the city. He only felt the intense pain of the spring season within his chest: the kind of pain a lover feels when he cannot be with the one he longs for. Never before had a young man attended so many events among the prisoners – farmers’ meetings, council meetings (which were useless anyway because women weren’t allowed to attend them) and every other conceivable event where he might run into Maria Skogh.

True, he did see her every now and then – it was unavoidable in a small town like that. And he did manage to exchange a few words with her every so often, but on the first such occasion he didn’t have the purse with him and he thought he would die of despair. And on the other occasions an opportunity hadn’t arisen or else he hadn’t dared. For a long time he would fidget with the purse in his pocket, but he was shocked one day when he noticed just how dirty it had become. He managed to clean it and tone up the colours a bit, but after that he didn’t dare carry it with him all the time. He had such an ache in his heart and his joy had almost vanished, he almost never joked with his work friends any more. He was no longer the same Vendel Grip they had known.

And then, completely out of the blue, the opportunity he had been waiting for suddenly arose.

It was the summer of 1715; he had just turned twenty-one and considered himself ripe for marriage. The prisoners arranged a summer gathering (“party” would be much too pretentious a word) and that was where he ran into Maria. And this time he had the purse with him.

And that was when he got the chance to give it to her, among the teeming crowds when everyone was leaving and Vendel had been following her with his eyes from the time he arrived until he left. He thought she was more radiant than ever; she seemed to be filled with joy – naturally from seeing him again, he thought – and she had been very friendly to him the whole time.

And then suddenly they stood very close to each other, pressed together by the crowds that were leaving. That is to say, Vendel had probably contributed a little to this closeness.

With fumbling hands he managed to give her the purse as he mumbled a few words, which weren’t at all the ones he had been practising all this time. It was highly likely that she didn’t register a single word.

Then he hurried away, still picturing her surprised and probing gaze.

For three days he walked around in a state of ecstasy.

On the fourth day Corfitz Beck came.

He wanted to talk to Vendel. In private. He looked fierce and pent-up.

They went into the empty workshop.

She can’t come alone, that’s obvious, Vendel thought. It wouldn’t be suitable. That’s why she’s sending Captain Beck who is a friend of the family. And naturally, Corfitz Beck doesn’t care to be used as a messenger in this way. It’s too bad, but that’s the way it is.

The captain turned round and stared at him coldly, “Listen Vendel, you’ve got to stop this immediately!”

Vendel’s heart sank like a stone. “Stop what, Captain?”

“Running after Maria like a lovesick tomcat. She’s very upset about it and her father is enraged. The whole thing is utterly embarrassing for me, don’t you understand?”

Vendel felt dizzy. But he fully intended to defend himself, and the love he felt was worthy of defending. “But Captain, I am serious!” he said defiantly, determined to stand his own ground.

“Serious? Just what’s got into you? Who do you think you are? You ... a common lackey!”

It had been years since Corfitz had referred to him in that way. They had been as good as equals for the past few years, and now ... ?

“When I took you with me to their house that time it was out of kindness, because your mother asked me to keep an eye on you. And this is how you repay me? By exposing her to unpleasantness like this ... it’s not something I ever expected of you, Vendel!”

“I haven’t offended Miss Maria in any way,” he answered, feeling a nasty lump grow in his chest. “On the contrary, I’ve acted completely properly and stayed in the background. I have never accosted her.”

“Oh, no? What exactly do you call this then?”

He slammed the purse on the table. It felt as if a bullet had been shot through Vendel’s heart.

“Maria thanks you for your kind thoughtfulness,” Corfitz said brusquely, “And quite frankly I think it was noble of her to say that.”

Vendel shut his eyes in agony.

“I had planned that with time, as I gained more wealth, I might ask her for her hand,” he managed to stammer out.

“Have you gone mad? Maria is engaged to me! And here you come, my maid’s son, and ... no, it’s just too much!”

Vendel stood completely frozen and felt himself slowly dying inside. His voice was like a whisper: “It won’t happen again, Captain.”

“No, I certainly hope not! Now,” Corfitz went on in a milder tone, “behave yourself in the future and choose your little crushes according to your class!”

Then he turned on his heels in military fashion and left quickly, having to bend as he walked through the low doorway and slamming the door behind him.

Vendel was left standing there with all his dreams shattered. Mechanically, he picked up the purse with one hand. He lifted it and examined it with both hands, as his young tears fell upon it. Then he wandered like a sleepwalker out into the blazing sun. It felt as though it was laughing scornfully at him.

There was now only one thing that Vendel longed for in his heart: to get away from Tobolsk and back home to Scania. He couldn’t face bumping into Maria or Corfitz Beck again, he couldn’t look them in the eye. The thought of death crossed his mind many times. How was he going to live on now that he couldn’t have Maria Skogh? But his survival instinct was stronger than that and he wanted to see his home again. He had had enough of war; King Karl was going to have to manage without him. There was, incidentally, no one in Tobolsk who knew where the king was at that time. The last they had heard of him was that he was stranded in Bender in Turkey. But that had been years ago.

At the beginning of their time in Tobolsk, Vendel had made a few sporadic attempts to escape. But it seemed impossible to get past the guards so he had given up before anyone discovered him. He wanted more than anything to avoid being sent farther east. So he had kept his head down and made sure that the Russians weren’t even aware of his existence.

That was before he met Maria.

The night after Corfitz Beck had crushed Vendel’s wistful hopes of love with what felt like a single sword slash straight through his heart, a fire broke out in the town. This was not an unusual thing, so no one took much notice of it. But they all ran to watch, thanking their lucky stars that it wasn’t their house that was burning.

But Vendel didn’t care about the fire. His soul had died. He went in exactly the opposite direction, down towards the River Tobol, which flowed past the town. Farther along he could see how it joined with the larger River Irtysh. He stopped and looked down at the fishing boats crossing the Tobol. They were on their way to do the night’s fishing.

Vendel had grown up to become a gorgeous young man of the blond Viking type: he was lean, tanned and had intense blue eyes. His thick golden hair was just as beautiful as always, and there was still a clear openness about his gaze. Except that now, of course, it was dimmed by sad and heavy thoughts.

As he stood there he was reminded of the fact that the Swedes weren’t the only prisoners in Tobolsk. There were also Russians who had fallen out of favour with the tsar and had been sent to the wilderness of Siberia as slave labour. He could hear a song in the quiet evening, a ballad that cut through his heart because it fitted his own situation. He couldn’t tell where the singing was coming from, but it was probably from one of the houses close by. A lonely soul had gone outside that summer evening and was expressing his gloomy state of mind.

Vendel translated the words in his mind as the singing went on:

Down in the valley the nightingale sings,

But I am a poor boy in a strange country

And am forgotten by everyone.

Forgotten, forgotten at so early an age,

An orphan am I,

My fate is so cruel.

Down by the river, on the beach, a young fisherman was struggling with his net. It looked as though he couldn’t untangle it and Vendel could almost see his anger. On the other side of the Tobol stretched the endless plains, not exactly a cheerful sight for Vendel. The sun was about to set, and he knew that the Ural Mountains were in that direction, but they were so far off that he couldn’t possibly see them. All he could see were the few farms that lay on the far bank, scattered clusters of trees in the outlying area of the taiga, and then the plains. Dry, barren and stony. Endless and eternal.

As he stood there lost in his own thoughts, he hazily registered that the song was still continuing, and his gloomy state became even gloomier.

Vendel felt more and more sorry for himself, more than he wanted to because he didn’t normally fall into self-pity.

I will die here, and be buried

and no one will know where

my grave is.

No one will ever visit my grave

but early each year

the nightingale will start to sing there.

Vendel let out a sob.

“No,” he thought, “No, I won’t die here. Mum, who was so distressed because I had to leave ... she must know that I’m still alive. She hasn’t deserved to suffer like this for so many years. Mum will be starting to get old. I want to see her again. I want to see all my friends back home, and the Scanian sky that is so clear and beautiful.”

He breathed heavily, as though he was trying to push his gloominess from out of his chest. His thoughts and will to live seemed to return to him. For a moment he looked back at the city with an almost wild look in his eyes – the flames still lit the sky but with a dull glow now. Vendel had no hope that there would be fewer guards so getting out of the town was out of the question, and anyway what was he going to do once he got out? The mere thought of the endless trek that would lie ahead through the plains and the taiga and on towards the Urals, which were teeming with wild animals, and then having to cross the mountains and walk through the never-ending Russian landscape wasn’t exactly alluring. Blond and with a distinctly foreign accent, how would he be able to manage? There were, of course, blond Russians, but not in these parts. Out here, people tended to be small and dark, a beautiful mixture of people of various origins.

The fisher boy ...

The Tobol ran east until it joined the main River Irtysh, which flowed in a northwesterly direction.

Westwards? Wasn’t that the direction he longed to go in?

Towards freedom?

The fisher boy looked terribly poor. And it was suddenly as though Vendel was exploding with energy. He hurried along the short cut that led to his house and collected all the money he had been saving. He had also managed to acquire a pair of boots and he took those too, as well as food and all the hides he had been working on plus his other belongings. Even though he rolled it all into a tight bundle, it was still a formless bulk that he could hardly carry under his arm. Then he calmly walked back down to the river. No one could see just how hard his heart was pounding.

From a distance he could see the young fisherman tossing his net angrily into the boat. He gathered up the rest of his fishing tackle and started walking up the riverbank, up towards Vendel. Perfect, thought Vendel as he waited for him in the shelter of the houses. When the boy reached the spot where he was standing, he stepped out of the shadows.

Vendel’s Russian was now good, so it was no problem for him to make himself understood by the young fisherman. He asked whether it was possible to purchase the boat, and if so, if he could do so right there and then.

The fisherman’s gaze was uncertain. He knew perfectly well what kind of man he had encountered, and it was forbidden for Russians to befriend those ungodly Protestants.

But Vendel discreetly pulled out a handful of roubles and kopecks that he had ready in his pocket. It was half of his hard-earned savings of coins. Initially he had been saving up to make an escape, later it was to marry Maria, and now he was using it for his original intention. He thanked his lucky stars that he had made sure to save so much.

The fisher boy’s eyes grew huge. There was perhaps the value of a whole year’s catch in the Swede’s hand. For that amount he could buy a new and better boat and still have enough to live comfortably for a good long time. Vodka ... girls ...

He bit his lip and looked around, and then he gave a decisive nod.

Vendel, who had been fidgeting with impatience and the fear of being discovered, let out a sigh of relief. “But quickly,” he said in a low voice. “And you’ve never seen me. The boat was just stolen. Understand?”

The boy nodded. On the other side of the river some women were busy carrying the day’s laundry up from the shore. Away in the distance he could see some other fishermen at their boats. And high on the slope was where the guards stood. “I just hope to God I make it past them,” Vendel thought.

He asked for some of the boy’s outer garments, since they were the kind Russian fishermen wore, and he also asked for his broad-brimmed cap, which gave some protection from the sun. The young man gladly agreed to the exchange because he was gaining the most from it. Vendel had become something of an aesthete. He had embroidered delicate patterns on his modest shirts and taken good care of his other clothes, as best he could in his impoverished circumstances. The clothes he was now getting in return would probably give him lice all over again. But it was a small price to pay for one’s freedom.

When they had exchanged their outer garments Vendel walked calmly down to the boat. He had tucked his hair under the cap and he tried to look as small as possible. The fisher boy had had a distinctive way of walking – he sauntered and was bow-legged. Vendel imitated him as best he could.

He took plenty of time arranging the fishing tackle in the boat; he pulled the net back up and worked on it a little. In the meantime he discovered that the boat wasn’t the best in the world, considering all the money he had paid for it, but there was nothing he could do about that. It was his route to freedom and he intended to use it!

He poled away from the shore like a natural fisherman as his blood thundered in his ears. Not once did he dare glance up at the guards on the slope.

As soon as he reached the current he felt the tug from the bigger River Irtysh. He sat down and grabbed hold of the clumsy oars, but mostly he just drifted with the tide.

There were several barges on the river, but most of the crews on board seemed to be completely engrossed in watching the fire. Fishing boats sailed in and out. Vendel turned his head away every time he passed them because the fishermen most probably knew the boat’s previous owner.

After he had passed the rather turbulent water where the two rivers joined, the current seemed to calm down. Since he was sitting backwards in the boat, he could see the town at all times and, more importantly, the guards. They hadn’t budged at all, just cast indifferent glances in his direction.

Vendel was just about to heave a sigh of relief when he caught a glimpse of something unexpected on the shore to his left. He didn’t dare look in that direction but from the corner of his eye he could tell that it was another watchtower. Naively, he hadn’t taken that possibility into account.

Slowly and meditatively he rowed with long strokes. He took his time looking at the banks, trying to find a good spot to cast the net. Closer to the town there was another fisherman who sat singing in his boat and he could hear a second one farther down the river.

Did he dare? Vendel liked Russian folk songs and he had learned many. He had also learned the unique Russian technique of pressing your vocal cords together.

But now it was a matter of life and death. At any moment the guards might summon him over so that they could get a better look at him and see whether he really was a fisherman.

Vendel sang with the courage of despair and his song was heartfelt and beautiful, matching his state of mind.

It is not the wind that bends the branches of the trees

not the puffin singing,

It is my heart that sighs and laments

like trembling autumn leaves.

Whether or not it was convincing, the guards let him row past them all the same. Maybe it was the calm, assured ease with which he sang that convinced them. Many of the local fishermen had a relaxed attitude to life and Vendel had often watched them at work on the river. He was now grateful for having done that.

The watchtower slowly glided out of his range of vision. The city of Tobolsk disappeared. The river grew wider. On both sides the taiga thinned out a little, and much of the landscape was steppe.

The fishing boats grew scarcer, as did the farms and the houses. The sun was way down on the horizon and would soon disappear, but Vendel had no intention of leaving the river on that account. Night-time was his friend and now the Irtysh was his mother, rocking him to freedom. He knew it was navigable all the way to a place called Samarovo. After that he’d have to see.

Until now the current had been carrying him westward, he could tell by the position of the sun. Or, to be more accurate, northwest.

Twilight came, early summer twilight, bewitching and light. Light veils of mist gathered about the scattered coniferous trees of the taiga forest. There was no sign of human life anywhere. Vendel was alone, terribly alone.

He was free! That knowledge suddenly rushed through him like thunderous applause. His painful thoughts of Maria and his sense of great shame had disappeared, as had his feelings of anxiety, insecurity and despondency.

Even though he didn’t really dare, he burst out singing an exuberant song about escape, “Holy Baikal”, which would have had him taken prisoner again on the spot had anyone heard him:

Hello east wind, stir up the waves!

Help the fugitive get farther away!

Even though the song was about the River Barguzin, which joined Lake Baikal from the east, it didn’t matter to Vendel. He felt as though the wind from the east was helping him home. He had left the city of Tobolsk and he was never going to see it again!