Читать книгу An Indecent Proposal - Margot Early, Margot Early - Страница 7

Chapter One

ОглавлениеIt was hot, a March hot where the heat came up from the bitumen in visible waves. Bronwyn and ten-year-old Wesley rode in the front of an ancient Toyota truck— no air-conditioning—and it was broiling. Bronwyn’s straight dark red hair blew dankly around her face, her skin stuck to her khaki slacks and the ripped vinyl upholstery, and Wesley was crying.

He was crying about Ari of course. Because Ari was dead. The only father Wesley had ever known had been in prison for his involvement with a crime syndicate. He’d been murdered in prison.

Sweltering, and certain the Vietnamese driver of the Toyota had emigrated too recently to have much English, Bronwyn spoke freely. “Please don’t waste another tear on him, Wesley,” she told him, which wasn’t something she would have said if her once-white blouse hadn’t been pasted to her body with sweat, if they hadn’t spent almost an hour crawling behind another ute on the winding road with no chance to overtake. Instead, she couldn’t restrain the impulse to tell her only son not to mourn Aristotle. “In fact,” she added, “it’s his fault we’re in this fix. It’s his fault you have to move away from your friends and go to a new school.” Once again, nothing she’d have said most days.

She spared a look at the tearful boy and past him to the driver. Mr. Le at the Asian market in Sydney had found this man for her and imparted the information that his name was Nam and he would drive the three hours to the Hunter Valley, her destination. Wesley sat wedged in the middle of the front seat between Bronwyn and Nam, head down. His hair was lighter than Ari’s and without even a hint of Bronwyn’s auburn. Nor were his eyes like Ari’s dark chocolate ones; they were hazel, not Bronwyn’s green. Just those wild recessive genes, Ari.

Yes.

Wesley held his soccer ball in his lap. He wore his shin guards and cleats and a child-size Socceroos jersey. He had others, as well, other teams, other countries. His dream was to be a professional soccer player. Better than a footballer, in Bronwyn’s opinion, even if Ari had owned a football team. Wesley had picked up the soccer thing from Ari, who had bought him a child-size Manchester United uniform. In any case, Bronwyn had never wanted to discourage her son’s dreams and now regretted that he was going to have to experience practicality the hard way. Not as hard as the way she’d learned as a child, though.

“And,” she continued, forgetting that she’d meant to comfort him, “your last name is Davies.”

“It’s not.” He spoke under his breath, but Bronwyn heard.

“Look, Wesley,” she burst out. “I know this isn’t fun, but we’re going to a place full of people who are probably willing to die for their horses, and I’d rather not share the last name of a man who is known to have been involved with doping them.”

“What does doping mean?”

“Giving them drugs. So they’ll lose or win or—I don’t know. But I do know that the name Theodoros is not going to be a passport to anyone’s friendship at Fairchild Acres.”

Wesley bounced his soccer ball on his knee, and Bronwyn put her hand on top of it. “Don’t do that. You’ll cause an accident.”

“Daddy doesn’t have anything to do with the horses at the racetrack. He told me.”

“Yes, well, I don’t mean it was him personally, and that’s only one aspect of his business. Ari was a criminal. He stole money, he cheated the government and he was involved in a lot of unpleasant things you don’t need to know about.” Bronwyn sincerely hoped Wesley would give up his hero worship of Ari without further examples of his perfidy. If it had been possible, she would have made a priority of protecting her son’s image of the man he regarded as father.

However, there had been too many explanations to make. How they had lost their home, cars, planes, bank accounts as law enforcement officials tried to untangle the web of criminal activity in which Ari had been involved. She didn’t hate Ari. She didn’t mourn him, either. Not now. She hadn’t the leisure. Leisure was gone, replaced with indigence.

And she’d sworn she would never be poor again.

Well, the joke was on her, but she’d grown up learning to survive on nothing. If she was angry now it was at herself for ever depending on anyone but Bronwyn Davies.

Now she was back to her maiden name but with complications she’d never had before she was married. Ari was dead, and Bronwyn Davies was glad for the simplification that offered in her own life. She was no longer married, need not obtain a divorce. Which was good. She barely had money to feed herself and her ten-year-old son. She did not have money for attorneys, for messy court battles. When Ari had first been arrested weeks earlier, she’d never considered divorce. In sickness, in health, in deceit and all that. But she’d grown tired of trying to offer Wesley meaningful explanations for things she would never understand: Why is my father a criminal? Why did he do bad things?

Just the thought of these questions made her tired.

I can’t think about Ari. I can’t think about some lag sticking him in prison. I can’t think about his face. Too many lies, not all of them his.

“I’m sorry, Wesley. I know you hate this, but you’ve got to trust me. This is how we need to keep ourselves safe. I know you love Ari—” the words your father definitely stuck in her throat “—and that’s fine, but we have to be practical.”

“We have to lie,” Wesley clarified.

Bronwyn wanted to swear. Now she was providing the duplicitous example. Also, it alarmed her how rapidly Wesley was becoming a cynic. It was one thing for her to be cynical; she had grown up sometimes literally homeless in Sydney because of poverty and had just discovered after ten-plus years of marriage that her husband’s actual job description was “gangster.” It was different when the cynic was Wesley, who was such a brave kid, ultimately, who wasn’t a whiner or a crybaby.

“This is going to be an adventure,” she told him. “You’ll like it.”

Bronwyn could have said, What would your dad think if he saw you crying? That would have stopped those tears in their tracks. Because, of course, Aristotle Theodoros had not tolerated tears in his male child. The child he’d believed to be his flesh and blood.

Well, Bronwyn had been repaid for her own deception now. Touché and all that. Which, after all, was the bigger marital betrayal? Maintaining a double life as a mobster or telling your husband that he was the father of a child who, even at birth, looked eerily like Patrick Stafford? A child who was Patrick Stafford’s son, not Aristotle Theodoros’s.

Then, Bronwyn spotted the first of the white fences and long green fields. Horse country, the Hunter Valley, home of Fairchild Acres, home of Louisa Fairchild and current residence of her great-nephew, Patrick Stafford.

“Wesley, look at the horses. Look how beautiful it is here. You’ll see. You’ll like living out here. Look at all that grass.” She cast a meaningful glance at his soccer ball, though she had no idea if her son would be allowed to play on the grass.

Beside her, Wesley said, for at least the tenth time that day, “I don’t like horses.”

Patrick Stafford gazed out the French doors of Louisa Fairchild’s blue brick Colonial house. Most of the homes in the valley were lowset, but not Fairchild Acres. The sprawling, graceful homestead was very different from the penthouse apartment where he’d grown up in Sydney with his parents. They had been stockbrokers, and Patrick had vowed to do something more meaningful with his life. Yet he’d ended up…a stockbroker. That was all right. He’d lost some romantic ideals along the way, become more pragmatic in general, and he was glad to be able to help people with their finances, as he was helping Louisa.

“Patrick, are you listening to me?” his great-aunt said now.

“Yes, yes.” Of course he was. When he’d first come to Fairchild Acres a month earlier, he’d been keen to confront Louisa, to demand answers; he’d wanted to know why she’d mistreated her sister, his grandmother. But gradually, he’d grown to love this elderly woman, as had his sister, Megan. When Louisa had been accused of murdering Sam Whittleson, he’d been outraged. An eighty-year-old woman kill a man she knew, a neighbor? He hadn’t believed it. And Louisa had been proven innocent, though the stress of her arrest had sent her into cardiac arrest, something she was quicker to forgive than he was.

His sister, Megan, now planned to spend her life with the arresting officer, Dylan Hastings. Yes, Patrick saw that both Dylan’s own misconceptions about Louisa and the orders of his superiors had led to his persecution of the older woman. But still! And now Megan was living with Dylan and his daughter and was planning to open a gallery and artists’ retreat.

So his own struggle was to release the last of his anger over offenses against Louisa that she herself had already forgiven.

In any case, this morning he had other preoccupations. While ordinarily he was the most attentive of listeners, today he kept thinking of the morning’s news. Just a recap of the events of the past month. Aristotle Theodoros had been murdered in prison two weeks earlier, and speculation was rife that he’d been killed to prevent him testifying against the Syndicate.

It had nothing to do with Patrick—not really. He’d met Ari briefly once, after Bronwyn had told Patrick of her engagement. It seemed a hundred years ago now. To Patrick, Ari had been the man Bronwyn chose over him. The man whose money she’d chosen over his lack thereof, no matter what else she’d claimed. Her rejection had put an end to his plans to do some graduate work in history, some writing, nebulous dreams.

He realized now he’d never been a writer.

He’d been born with his parents’ fine-tuned instincts for the stock market. They’d died when he was eighteen, but they’d left him and Megan comfortable. His university goals had reflected that ease, he supposed. It had taken a shallow woman’s ridiculing his dreams to make him see his own future clearly.

Well, hers certainly hadn’t worked out. Aristotle Theodoros’s assets had been seized, and Patrick would have needed the soul of a saint not to enjoy the irony. Weeks earlier, he had caught one glimpse of Bronwyn on the news, her auburn hair in a French twist, Chanel sunglasses, white linen suit, Italian sandals, looking unfamiliar, haughty and distant as she left the courts after Ari’s arraignment. Inadvertently, he was sure, the mercenary woman he’d once believed he loved had married a crook; and now the crook’s money was lost to her.

“I want to know what you think,” Louisa repeated, “about how this will affect the ITRF election.”

How what will affect it? Patrick didn’t want to admit just how inattentive he’d been. Andrew Preston, the American candidate for the presidency of the International Thoroughbred Racing Federation, had publicly supported Louisa when she’d been arrested. His generosity had set the stage for a tentative but positive relationship between his family and hers, but Louisa still seemed to prefer media giant Jacko Bullock. Patrick couldn’t share her predilection. The Bullocks, Jacko and his father, Mezner, were in the pocket of people like Ari Theodoros—or so Patrick believed.

A Toyota turned down the driveway, then stopped at the gatehouse. The guard spoke briefly with the driver before the truck continued its approach. It was ancientlooking—and sounding. A muffler would be a good idea. The driver was Vietnamese, Patrick thought, maybe one of Louisa’s gardeners. He considered speaking to the man about getting the four-wheel drive fixed, and then he saw it draw to a stop outside the entrance to the kitchen. A woman with long, very straight auburn hair climbed out, followed by a boy in a soccer uniform, who promptly began playing with a soccer ball he’d brought with him, dribbling, popping it in the air, regaining control, until the redhead told him to stop.

“Perhaps if you looked at me, Patrick, you would hear what I’m saying.”

“What?” He spun around.

His great-aunt turned sympathetic eyes upon him, an unusual move for Louisa, who was straitlaced and not given to sympathy for herself or anyone else. “Are you worried about Megan being with Dylan?”

“Of course not,” he said, though that wasn’t strictly true. Dylan had regarded Louisa as the chief suspect in Sam’s murder, but he had also been the one to track down Sandy Sanford, the real killer. And he had to admit, in comparison to some of the men Megan had dated in the past, Dylan Hastings was a dream come true. And Dylan’s teenage daughter seemed to add new dimensions to Megan’s life; the two were quite a pair with their shared interest in art and fashion, among other things. “No, I’m sorry. I was thinking about this morning’s news. I apologize.”

“Aristotle Theodoros,” Louisa said with a snap in her voice. “Lower than a snake’s belly. I’m tired of hearing about the man.”

“You’ve met him?” Louisa was a wealthy and powerful woman. It didn’t surprise Patrick to learn she may have met Theodoros at some point.

“Well, of course,” she replied irritably. “His television show sold racing predictions. I was not at all surprised to learn he was involved in doping horses. I’m glad someone finished him off. It will save the country the money that would have been spent prosecuting him.”

“Do you think he was murdered,” Patrick asked, “to keep him from telling what he knew?”

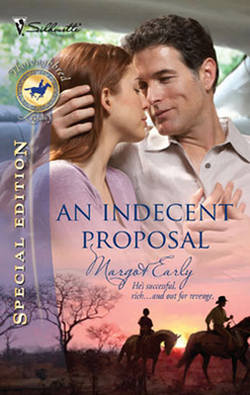

“Probably.” She gave a small snort. “People like that just give the sport a bad name. I know it’s a cliché to say so, but it’s a fact. Then people think racing is populated by underworld characters. Or they think it’s all about money. Some people don’t understand what it is to love horses and to love to see them run, especially an animal who loves running, a great horse whose heart will spend itself to win, win, win. An Indecent Proposal, for instance. That’s a horse. There’s spiritual beauty in horseracing, Patrick, and then on the other side are people like Aristotle Theodoros. Parasites.”

Patrick turned his mind firmly to matters of the present. “How can you be sure Jacko Bullock isn’t one of those?”

“I can’t be. But I trust him more than I do Andrew Preston.”

“What do you have against Preston?” Patrick tried to keep his voice neutral.

Louisa’s face tightened slightly. “I don’t like change, Patrick. That’s all. And I don’t like situations I can’t control.”

Patrick agreed with the sentiment that Andrew Preston wasn’t about to be controlled by anyone. His mind’s eye, however, continued to see the long, straight auburn hair of the woman who’d gotten out of the Toyota, reminding him of another woman with long, straight auburn hair.

“Wesley,” Bronwyn hissed at her son as she finally persuaded him to sit on a stone wall outside the head housekeeper’s office. “I’m trying to get a job,” she said, moving her full-size backpack—one that had belonged to Ari—and Wesley’s smaller tote bag so that they sat together. Bringing everything she owned to Fairchild Acres hadn’t been practical. Instead, she’d hired a small—very small—storage unit in Sydney and prayed that she’d find a way to pay the monthly rentals until she could collect the rest of her belongings, belongings for which she was pretty sure there would be no room in the Fairchild Acres employee bungalows.

“It’s important that you are quiet and stay out of the way here,” she continued whispering to her son. “I have to have this job. Don’t you see that? We have no money since your— Anyhow, we have to make our own way, Wesley, and that means I have to work.”

“Why couldn’t you get a job in Sydney?”

“It’s expensive to live in Sydney.” This wasn’t the whole reason for her calling about the job she’d seen advertised at Fairchild Acres, however, and Wesley seemed to know it.

He said, “You always think you’re smarter than everyone else.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Like Nam. You thought he couldn’t understand English.”

Bronwyn’s cheeks burned anew. When she’d bade their driver farewell, he’d said in perfect English, “He must have caused you a lot of trouble.”

Ari.

Well, that was one way of putting it.

Yes, it was easy to blush, remembering her mistake.

“Wesley, could you please sit here quietly while I go in for my interview?”

“What if you don’t get hired?”

Bronwyn didn’t want to think about that. “I’m going to get hired. Now stay here. Don’t wander around.”

She approached the door of the estate manager’s office, which was labeled Office, as she’d been told it would be. She knocked, and as she did, a small, extremely pretty young woman with short blond hair looked out of the next door, which stood open. It appeared to be the door to the kitchens, though also part of the main house.

“She’s not here,” the woman called.

“What?” Bronwyn turned.

“Are you here about the dishwasher’s job?” the blonde asked.

Bronwyn nodded, noting the perfection of her skin and thinking that Patrick Stafford had no shortage of beautiful women at Fairchild Acres. But he probably had a girlfriend, for all Bronwyn knew. She certainly wasn’t here to resume any romantic relationship with him after a ten-year separation. Nonetheless, this pretty female made Bronwyn want to find the nearest sink and mirror so she could clean up after the hot, dusty truck ride. How could anyone come out of that obviously steaming kitchen looking so good?

“Well, Mrs. Lipton is gone for the day. She’ll be back tomorrow. You’ve come on her day off.”

“But I have an appointment.” This was impossible.

“You’re the woman who’s supposed to be coming tomorrow?” the blonde asked, her eyebrows drawing together.

How could there be such a mix-up? Bronwyn wondered. It was late in the afternoon and Nam had already headed back to Sydney. Not that she could have afforded to have him make the trip again the next day. Were there hotels nearby? Bronwyn wasn’t destitute, but she didn’t want to spend any of the little cash she possessed. She could live on the smell of an oily rag better than most, but there was no point in depleting her resources unnecessarily.

“Look, I’m Marie,” said the blonde, sticking out her hand, which Bronwyn took, grateful for the offer of friendship which the woman seemed to be making.

“Bronwyn Davies.”

“Yes, now what you want to do is go over to that door and go in and find Agnes. She’s the assistant housekeeper, and I dare say she’ll find you a place to sleep tonight. Is that your boy there?”

“Yes, that’s Wesley.”

Marie nodded, smiling. “He’s a handsome one, isn’t he?”

“Too handsome for his own good,” Bronwyn admitted. “He’s been known to get away with plenty.” She hesitated. “Which door?”

Marie pointed, and Bronwyn turned to see where she’d indicated.

“Right. Well, thank you.”

“No worries.”

As Marie ducked in the kitchen, Wesley said, “Brilliant, Mum. Wrong day.”

Bronwyn nodded in resignation. “Well, you better come with me.” She stooped to shoulder her heavy pack then fastened the hip belt. Wesley picked up his tote, swinging the strap over his shoulder. Bulging with his most prized possessions, the bag seemed to dwarf him, and Bronwyn thought how very young he was to have to go through all that he had in the last months—culminating, of course, in Ari’s murder.

I’ve got to stop saying nasty things about Ari, she thought.

After all, Wesley loved the man, loved his memory still.

Bronwyn, too, had loved Ari. Once.

I can’t think about it, about any of it. Unlikely as it might have seemed that she had loved a man twenty years older than her, that had been the case. Probably her attraction to him had something to do with the fact she’d never known her own father, who’d died before she was born, leaving Bronwyn’s mother to fend for herself and her infant in urban Sydney.

Bronwyn would do a better job of that than her mother had. She and Wesley were not going to do any sleeping under bridges—or in shelters, for that matter.

She said, “Wesley, you’re the best, y’know?”

“Mmm,” he answered.

She led the way up a red stone path to the door Marie had indicated. As she turned up the path, the door at the end opened, and a man stepped out.

Her breath caught, and she stumbled on the walk. Graceful, Bronwyn.

She would have known him anywhere, and already her eyes were seeking out that cleft chin, the jaw and delicate yet prominent bones she remembered in his face. His medium brown hair was a little too long, parted on the side, and still had a tendency to dash across his hazel eyes.

The eyes Wesley had inherited.

Patrick Stafford stopped in his tracks. He paused, gave her one derisive look, and said, “Why doesn’t this surprise me?”