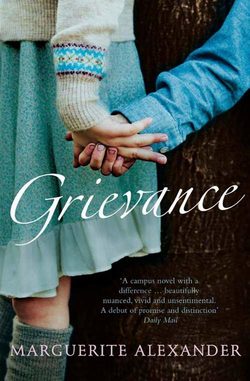

Читать книгу Grievance - Marguerite Alexander - Страница 7

Ballypierce

ОглавлениеNora’s earliest precise memory is of a day shortly before the birth of her brother. She remembers that the baby’s imminence hung in the air that afternoon, charging the atmosphere and releasing in her father a restless energy. Always a boastful man, his pride in himself, and in her, seemed to know no bounds. And while she is sure, without having a clear memory of them, that there were other, similar occasions before that afternoon, she knows that there were none afterwards. This, she thinks, is why she remembers the afternoon so clearly, that it marked the end of an era: with Felix’s birth, another, altogether different, phase in their lives began.

She remembers sitting on the counter in her father’s shop, surrounded by a group of admiring men. The pretext for her being there was that her mother needed to rest. Her father had come home for lunch, as he was in the habit of doing when it was just the three of them, leaving in charge one of the succession of young women that he had working for him. His routine was sufficiently established for people to know not to take in their prescriptions over the dinner hour, when many of the other shops, which couldn’t afford extra help, closed. Her mother had told him that the midwife had called, that her blood pressure was up again and she needed rest.

‘Will I take the wee girl back with me, Bernie?’ he had asked.

‘Since when have you needed my permission?’ her mother had replied.

It was acknowledged between the three of them that she and her father were a team, and while her mother boasted of this to her acquaintance – the degree of interest that Gerald took in his four-year-old daughter was sufficiently unusual to arouse the envy of other women – her resentment at being excluded sometimes surfaced at home. Nora was hoping that the baby would be a boy, not for herself or her father, who were perfectly content, but for her mother. She and the baby boy would then form another self-contained team and the family would be perfectly balanced.

So Gerald took her back with him and she spent the first hour or so sitting at a little desk that Gerald had rigged up for her in the corner, drawing and doing a few sums that he had set her. Really, this was only marking time until a sufficient crowd had gathered, mostly other shopkeepers who had left their wives, now released from kitchen duties, in charge while they slipped out for half an hour.

Without understanding at that point precisely why, she knew that it was a mark of her father’s importance that his shop acted as a magnet for men with time on their hands during the slow, early-afternoon hours before the schools were out. Ballypierce was a largely nationalist town where incomes were low and trade rarely buoyant. But Gerald, who had grown up and gone to school with many of the other traders, was a great man among them, a pharmacist who had gone to Belfast to study. They could leave their shops, but he had to stay at his post to make up prescriptions, apart from the hour dedicated to lunch, when he insisted on a home-cooked meal. He was one of the few whose family didn’t live above the shop, having chosen instead a new bungalow, built to architect’s specifications on a hill at the edge of the town with a view over the valley. The flat above the shop was let so he was a landlord in addition to his professional status.

People might not have jobs but they still became ill and needed medicines that the Health Service funded so, whatever else was happening, the Doyles were always comfortable. And Gerald, instead of joining the Protestants at the golf course or sailing club, as he was entitled to, had stayed one of them, always ready for good craic, always pleased to see an old friend who dropped in. By comparison with others in the town, his shop was like a palace, with large plate-glass windows on both sides of the door, all the fittings built to the highest standards, always sweetly smelling from the soaps and perfumes and ladies’ cosmetics, and gleamingly clean, because Gerald insisted on the highest standards of hygiene and had been known to sack a girl whose hair always looked unwashed. And when the party was under way, Gerald would send his assistant into the little kitchenette to make them all cups of tea.

That afternoon Nora was lifted on to the counter, the one with the little room behind it where Gerald made up his prescriptions. She was wearing a navy blue smocked Viyella dress with matching tights – Gerald had requested that Bernie change her before they left – and her hair was tied back into a tight ponytail. When Gerald had started this routine, as soon as she could walk and talk and had no need of nappies, she would recite a few nursery rhymes or count to a specified number, but since he had taught her to read she was always required to show off her current level of attainment. That afternoon she read from a simplified picture-book version of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

‘You’re a great girl, so you are,’ said Malachy McGready, the greengrocer. ‘It’s no wonder your daddy’s so proud of you. But if he gives you books like this to read, you’ll start to think you’re a wee Brit. You won’t find many Susans and Edmunds around here.’

Gerald gave a satisfied little smirk, having come prepared for just this rebuke. ‘Don’t you know who C. S. Lewis was?’ he asked. ‘Your man was born in Belfast and ended up a professor at Oxford.’

This was greeted with smiles all round, not so much that one of their own (they were by no means convinced that a man who wrote like this could be so described) had achieved so much in the wider world but because Gerald had outmanoeuvred them yet again. These afternoon gatherings, whether Nora was present or not, were not so much exchanges between equals, as enactments and affirmations of Gerald Doyle’s superiority, and if he had ever been caught out or bettered, they would have felt keen disappointment. Malachy’s scepticism was, none the less, a necessary component of the drama.

‘Is that what you’re after for the little lady here – for her to be a professor at Oxford? What’s wrong with Queen’s, or Trinity, if she must leave home?’

‘I want the best for her, and she deserves it. And if when the time comes the best is still Oxford, then we’ll have to make the sacrifice.’ As he spoke, Gerald looked down fondly at Nora, who sat swinging her legs and munching a biscuit.

‘But tell me, Gerald, your man, Lewis,’ said Malachy, who had picked up the discarded book and was peering at it to make sure that he had the name right, ‘would I be right in thinking he was a Protestant?’

‘Well, you would, of course. How many Catholics do you suppose went from here to Oxford before the war?’ There was that in Gerald’s manner of a man who is playing a game so elaborate that his opponent, at the moment of thinking he has caught him out, finds himself the victim of superior strategy. Gerald’s air of victory took no account of his having ignored the drift of Malachy’s argument. Then, with a sudden shift of tactics, he addressed the point that Malachy had been labouring. ‘You want to know why I give Nora stuff like this to read? Because it’s what the children of the ruling classes read, and if you want them to get on in that world, you give them a head start. Rather than have her, at forty, feeling aggrieved at the way the world has treated her, I want her out there with the best of them, showing what can be done.’

A number of them felt mildly rebuked by this, but they would no more have thought of challenging him than they would a geometric theorem or a doctor’s diagnosis. Gerald loved imparting information, surprising people, overturning their expectations; and while he needed a patsy like Malachy in order to shine, none of them was prepared to risk losing his goodwill and, with it, the dim reflection of his glory that touched them as welcome members of his circle. They enjoyed the sense of inclusion that allowed them, later, to say to a wife or customer, ‘Gerald Doyle was saying to me only the other day…’ Besides, they believed, because he had told them, that his was the voice of science, reason and progress, and they were all reluctant to pit themselves against these mysterious forces. If he seemed more than usually pleased with himself that day, they put it down to the imminently expected baby, and were prepared to indulge him.

‘The teachers will have their work cut out when she starts school,’ said Liam Doherty, who owned the best of the nationalist bars. ‘You haven’t left them much to teach her.’

‘It’s a problem, right enough,’ said Gerald. On this particular point, if on no other, he was prepared to acknowledge himself baffled. ‘But there, I almost forgot. I’ve been looking into Shakespeare with her, and her memory’s prodigious. Come on, darling,’ he said to Nora, as he lifted her down from the counter and gestured to his companions to clear a space around her. ‘Show us how you do Shylock.’

Nora composed herself briefly, then stretched our her arms and recited, ‘“I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?”’

After the first two short, monosyllabic sentences, this was delivered in the chanting monotone of small children reciting prayers that are beyond their understanding – a style that she had learned not from Gerald or from her mother but at the little nursery she attended in the mornings, where prayers were part of the routine.

Then, after a look of encouragement from her father, she shifted her position, hunching her shoulders into a forward stoop and holding out her right hand in a grasping gesture. ‘O my ducats, O my daughter, O my ducats, O my daughter,’ she growled, with as much depth, intensity and malice as she could muster. When she had finished, she ran over to her father and clutched him round the knees.

Her audience was genuinely speechless, not sure what to make of her performance, for all its precociousness. As was customary, it was Malachy who found a way of expressing their doubts: ‘This Shylock,’ he said tentatively, ‘wasn’t he a fellow?’

Gerald nodded. ‘The Jewish moneylender. The first Jew in literature, when writers weren’t afraid to tell the truth.’

‘She says it bravely,’ said Malachy. ‘I doubt there’s another girl her age who could match her. But were there no girls’ parts you could teach her?’

Gerald nodded slowly. ‘I looked into it, of course, but most of the young girls in his plays are only interested in love and such like and I didn’t want her head filled with that kind of nonsense. Now Portia’s different, of course. I tried her out with the “quality of mercy” speech, but there were words that even she couldn’t get her tongue round, and you have to be careful with a child like this not to tax the brain with more than it can handle.’

There were murmurs of approval for Gerald’s commendable fatherly concern. These he stilled by raising a warning finger. ‘But don’t make any mistake about it,’ he said, ‘They can’t learn soon enough how the world works.’

‘You want her to know about the Jews?’ asked Liam, doubtfully. This struck all of them as an entirely unnecessary lesson. As Irish Catholics, they had never questioned the received wisdom that Jews were treacherous, money-grubbing and only out for themselves. On the other hand, none of them had ever met a Jew, or was likely to do so.

‘I want her to learn something much more useful than that,’ said Gerald, who was, as usual, a step ahead of them. ‘I want her to realise that, not just in this instance but in almost everything you could name, people’s instincts are being suppressed by those who think they know better. Now, take the Jews.’

‘I’d rather not, thank you,’ said Tom O’Neill, the butcher, raising the biggest laugh of the afternoon.

‘Very well, then. Take Shakespeare and the Jews. Now, the English are only too ready to accept what he has to say about England – all that jingoistic nonsense about sceptred isles and brave English soldiers throwing themselves into the breach, without knowing that he was more or less forced to write it, but they don’t want to hear what he says about Jews. And yet the man was ahead of his time. He said – you heard the girl – that they’re not animals, they’re human beings, like the rest of us. They bleed, they laugh and all the rest of it. I’ll go along with that. But – and it’s an important “but” – revenge matters as much to them as food and drink, and they don’t have the same feelings for their flesh and blood as we do. His daughter runs away, and all he can think about are his ducats. But you’re not allowed to say that any more, not in England or the States. No, I just want her to learn to respect the evidence and to be fearless in saying what she knows to be right. That’s all. The Jews are incidental, they’re just an example.’

Signalling that the session was over for the afternoon, he lifted Nora up and held her, legs dangling, face on a level with his, as if he were displaying her. ‘And I want her to know that she’s more precious to her Daddy than anything else in the world, even ducats. Especially ducats.’

There was no doubt that they made an appealing picture – Gerald fresh-faced, well-tended (it was rumoured that he took home some of the lotions and creams from the shop for his own skin, and that he needed a wife at home all the time to iron the shirts that he insisted on wearing, clean, every day), dressed in the finest tweed, linen and leather, a man in the prime of life, and Nora as dainty and delicate as a little fairy.

‘And what if the next one’s a boy?’

‘It’ll make no difference. There isn’t a boy who can match her.’

Nora’s companion memory to what was to be the last occasion when her father took her to the shop with him to demonstrate her cleverness fell within days of the first. The two stand side by side, an end followed by a beginning. Everything about that second day was different, from the moment she woke up and sensed an alteration in the sounds of the house. Still in her pyjamas, she wandered through into the kitchen where her mother would be preparing the breakfast – hers to be eaten at the kitchen table, her father’s to be placed on a tray and carried through to him in the bedroom. Instead of her mother, however, there was Mrs Daly from next door, a woman of late middle age, whose children had grown and left home, moving about and, as she described it, making herself useful.

‘Now, pet, you mustn’t fret,’ she said. ‘Your daddy’s taken your mummy into the hospital, and when she comes home, please, God, she’ll have a new wee brother or sister for you. Now, what would you like for your breakfast? Will I cook you an egg or fry you a rasher?’

Nora sat and spooned cereal into her mouth while Mrs Daly pushed a cloth over the work surfaces in a show of activity. She wondered how her mother felt about having another woman in her kitchen. She knew her to be ill at ease with her neighbours in this most select area of the town and that she suspected Mrs Daly, who had time on her hands and an imagination actively engaged in the lives of others, of a tendency to snoop.

Bernie often said that her neighbours regarded her as fortunate, not just because they lived so well but also because, as an exceptionally pretty young woman, she had caught Gerald’s eye when she had come to work as an assistant at the pharmacy. And she suspected that ‘fortunate’ carried connotations of something in excess of what she deserved. Convinced that everybody around her was looking for evidence against her, she was an anxious, if unenthusiastic housekeeper, and kept her family, modest country people of whom she was now ashamed, at a distance.

There was to be no nursery this morning, and Mrs Daly was clearly relieved when, after breakfast, Nora demonstrated that she was quite capable of amusing herself. Although she wasn’t very good at playing with toys, she had other resources, and after she had spent some time drawing and looking through books, she put on her rubber boots and jacket and wandered round the garden while Mrs Daly sat with yesterday’s newspaper at the picture window in the lounge, keeping an eye on her.

At this time Gerald took considerable pride in his garden, which deteriorated sadly in the years that followed, and Nora, in her progress, named the shrubs and bulbs that were in flower, as her father had taught her: magnolia, viburnum, the quince-bearing japonica and daffodils. The daffodils were a concession to popular taste, as represented by Bernie: for himself, Gerald favoured those plants that his neighbours couldn’t identify when they passed the time of day with him while he was working in the garden. Nora talked to herself as she padded through the damp grass, conducting an endless conversation in her head – a habit that persisted with her into young adulthood.

She was growing hungry and thinking it must nearly be lunchtime when she noticed that Mrs Daly was no longer at her post by the window. Assuming that the old woman must be preparing something for her to eat, she went back into the house, took off her boots as she had been trained and, without putting her indoor shoes back on, passed through the central corridor in the bungalow to the kitchen, which was at the front of the house facing the street. The architect whom they had consulted after buying their plot of land had convinced Bernie that, with his design, she would have a livelier time while she was working, but she had always felt exposed in there and had come to resent his advice.

Just before she reached the kitchen, Nora heard voices, those of Mrs Daly and another woman, who seemed to be telling her something. They were speaking softly, but there was an undertow of excitement; suspecting that they would stop if she joined them, Nora hovered outside the door, which was ajar, as though someone had gone to close it without checking that it had held.

‘Lord love us,’ she heard Mrs Daly say. ‘Who would have expected such a thing?’

‘It can happen to anybody,’ the other woman replied.

‘But the Doyles, of all people,’ said Mrs Daly. Then she used a word that sounded to Nora like ‘gerbil’. They didn’t have pets, but Nora had once seen a gerbil when she had gone to play with Katy, a girl who lived in one of the neighbouring houses. It was a little rat-like creature in a cage, and when Katy had lifted it out, petted and kissed it, the sight had sickened her and she had refused all subsequent invitations to play. Why would Mrs Daly bring gerbils into a conversation about her family? But then, as the women continued, it seemed that they were talking about her mother’s new baby. Trembling, she crept away down the corridor and, not knowing what else to do, put her boots and coat back on and went out again into the garden. She didn’t feel hungry any more so she sat huddled on the bench wondering what to do.

She felt numb with cold and misery but never considered approaching Mrs Daly for comfort or enlightenment. She had already absorbed some of her parents’ pride and touchy reserve about anything that might reflect less than well on them, so she had no intention of letting the two women, whose presence in her house she now deeply resented, see her fear, shame and bewilderment. She didn’t want them to know that she had overheard their conversation, so she sat there and hugged to herself the horrific possibilities that the word ‘gerbil’ had unleashed.

Nora stayed in the garden until Mrs Daly, with a great show of bustle and concern, came out to get her.

‘Whatever can you be thinking of, pet, to stay out here for so long, catching your death?’

Nora knew that, in the grand scheme of things, it was Mrs Daly’s task to call her in, and that she had suddenly woken up to the time she had allowed to pass while she was gossiping in the kitchen with a woman who had no business being there anyway.

‘Now, you come inside and warm yourself up while I make you a bit of dinner. I’ve had a wee look and there’s sausages, ham, fish fingers, soup. You just tell me what you’d like.’

She allowed herself to be led into the house, but eluded all Mrs Daly’s attempts to take her by the hand. When they reached the kitchen the other woman had already left, as Nora had suspected would be the case. She sat, composed and docile, at the kitchen table, while Mrs Daly heated some soup and toasted bread for them both, and although her appetite had not returned, she forced herself to eat a few mouthfuls. More than anything, she didn’t want Mrs Daly to know that she had heard the word ‘gerbil’, as though the word itself had a special power and the mere act of saying it might bring into being what she most feared. She felt sure that, if the subject were raised, Mrs Daly would smother her with a pity she didn’t really feel, for what she had picked up from the overheard conversation wasn’t concern but relish in other people’s misfortune.

Besides, she was trying to convince herself that what she had heard was a mistake. Nothing was real unless her father told her it was so, and she remembered now her father’s poor opinion of women like Mrs Daly, whom he described as ignorant and superstitious, and on one occasion had had to explain to her what he meant by ‘forces of darkness’ when something that had upset her mother was being discussed. When her father came back from the hospital Mrs Daly, who seemed to Nora to be swelling with importance, would wither and disappear back into her house.

In the middle of the afternoon, while Nora was doing her best to occupy herself in her bedroom, the telephone rang. She heard the kitchen door close before Mrs Daly answered it. Then, shortly afterwards, it rang again, and after that it seemed that it never stopped.

Finally Mrs Daly appeared at her bedroom door and said, ‘That was your father, pet. They’re waiting for an ambulance to bring them back from the hospital. Then they’ll all be home.’

Nora nodded. It seemed that the baby had indeed been born, but Mrs Daly was volunteering no information about it.

‘Will you come and sit with me?’

‘I’m fine, thank you.’

When, shortly afterwards, she heard the bustle of arrival at the front door, Nora went and sat on the floor, her back to the wall, waiting to be called. There were sounds of movement, and strangers’ voices, and then she heard Mrs Daly say, ‘The Lord love him, the poor wee boy. But they do say they bring luck to a house.’

‘They do, do they? Well, I suppose “they” would know, whoever they happen to be,’ said her father. ‘And who told you anyway? Did I say anything to you about this baby?’

‘Well, Mary Donovan popped in. She has a friend, a nurse at the hospital who—’

‘So, the bush telegraph has been functioning as well as ever, I see. I wondered why it was taking me so long to get through on the telephone in my own house.’

‘It wasn’t like that. Don’t make it so hard for yourself, Gerald. I know it must be a terrible shock, and my heart bleeds for you, but everybody wishes you well.’

‘Do they? Do they indeed? Just as they say this will bring me luck? Well I’m sure that will be a great comfort to me.’

Rigid with fear, Nora lay on her bed. Normally, she was his first thought when her father entered the house, but muted sounds of conversation, and the louder noises of people moving about, continued outside, and nobody came to get her. Straining her ears, she thought once or twice that she was picking up new and unfamiliar sounds, of a tiny living creature hovering somewhere between human and animal, but she couldn’t be sure. Then the doorbell rang, and shortly afterwards rang again, and she heard the clear, measured voices of men other than her father.

Suddenly she could bear the suspense no longer. She went out into the empty hall and tracked the new voices to her parents’ bedroom, but the door was closed. She wandered into the kitchen and there was her father, standing at the kitchen counter staring at the teapot and waiting for the kettle to boil. He turned when he heard her and looked at her, not as if he had never seen her before but as if he now saw her differently and was having to make up his mind about something.

‘The house is full of priests and doctors and it’s all cups of tea and little snacks, though if I know Father McCaffrey there’ll be no leaving this house until he’s seen the whiskey bottle.’

‘I’ve a baby brother, then,’ said Nora.

‘That’s right,’ said Gerald. ‘And I have a son. What every man’s supposed to want. Am I not right? They do say, be careful of making a wish, it might come true. You know what’s going through my mind?’

Nora shook her head.

‘There’s this book, Nineteen Eighty-four, written by this Englishman, years ago, before anybody knew what 1984 would be like, but he made it sound like the end of the world, the people not really human – not what you could call human – any more. Well, this is 1984, so we must give him the credit for getting something right.’

He loaded the tray with tea and fruit cake, cups and saucers, milk jug and sugar bowl, and Nora realised she had never seen him perform even the smallest household task before. All that had been left to her mother. In its way, the sight of her father fussing over cups and saucers was as frightening as anything else that had happened that day, and she wondered whether that was the way it was going to be from now on.

Lifting the tray, he said, ‘I’ll take this through to the vultures who’ve come to prey on our misery.’

When he had left the room, Nora sat at the kitchen table, eating the cake crumbs and bits of dried fruit left in the tin. Her father hadn’t asked her if she had eaten, what kind of day she had had, how Mrs Daly had been towards her. He hadn’t said when he would be back to attend to her, whether her mother had been asking for her, or given any clue as to how life would proceed. All these concerns had to a degree displaced her fears about the baby, but she was also doing her best not to dwell on her new brother. In particular she avoided visualising him. She sat there while the telephone rang intermittently and was answered elsewhere in the house, staring at the empty blackness of the window, where nobody had thought to draw her mother’s flower-patterned curtains.

After what seemed a very long time, she heard her parents’ bedroom door open, and then her father was with her again.

‘You’d better come in,’ he said. ‘Father McCaffrey and Dr Murphy want a word with you.’

He didn’t take her hand but led the way to the bedroom, where he waited at the door while she went inside. He didn’t go in himself, but closed the door behind her from outside. Opposite, her mother was sitting up in bed, with the cradle she had prepared for the baby beside her. She gave Nora a wan smile, as if everything was out of her hands. This in itself was not unusual since, within the family, she had always seemed the least powerful of the three, taking directions from her husband on most household matters, and resentfully acknowledging that she came after Nora in his affections.

What was more startling was that, while she was recognisable of course, she seemed completely different, as though she had been rearranged. She looked as though something had happened to her face, though it was impossible to say what. Nora carried around with her the memory of her mother’s face that day and, years later, when she heard a woman describe herself as ‘shattered’, by what seemed to Nora a rather trivial event – she came to judge much of the substance of other people’s lives as trivial – she thought, ‘Yes, that’s it. She had been shattered, broken up and hastily put together again, but none of the pieces fitted in quite the way they had before, not any more.’

At the foot of the bed were Father McCaffrey and Dr Murphy, one on each side, like guardians. Nora saw a look pass between them and, after a nod from the priest, the doctor cleared his throat.

‘Well now, Nora,’ he said. Nora had often been taken to visit him, or had received visits from him at home, and he was always brisk and reassuring. Now he was frowning with concentration, as if struggling to find a manner appropriate to the occasion. ‘We thought you should be told – it’s always best to be clear about these things from the beginning. Your little brother has what’s known as Down’s syndrome. At one time he would have been called a “mongol”, a term you might still hear people use, but now we prefer Down’s syndrome, after the man who discovered it.’

Before he could go on with his explanation, Father McCaffrey, who appeared to think that the doctor had struck the wrong note, interrupted: ‘These are very special children, Nora. Special to God, who wants us to cherish them, so he only sends them to those families he knows will give them the love and care they need.’

Nora said nothing, as she tried to assimilate the implications of ‘special’. She had always been led to understand that she was special, but there was evidently more than one kind of special.

As if sensing her confusion, Dr Murphy said, ‘He won’t develop in quite the way you have, he won’t learn so quickly. But you’ll find yourself surprised at some of the things he can do and he will be a very loving brother to you.’

‘Exactly,’ said Father McCaffrey. ‘They’re generally very loving, and you shouldn’t bother your head too much with what he can and can’t do. Too much is made of all that in the world today. He’ll be special to God because of his innocence, and that’s a very precious gift indeed.’

Nora nodded, feeling that something was required of her, but really her mind was elsewhere. The doctor had said ‘mongol’. That was what the word had been, not ‘gerbil’.

‘Now, I know we don’t need to tell you to be a really good girl, and to help your mother and your wee brother as much as you can,’ said Father McCaffrey.

Nora glanced across at her mother. She certainly looked in need of help.

‘Now, why don’t we leave you here, to start getting to know your brother and to have some time with your mummy?’ the priest concluded. The doctor said something to her mother about visits and midwives, then they both turned to go. On their way to the door, however, the doctor paused briefly to catch Nora’s eye and give her a sad smile.

Everything about that day had been strange – not just Mrs Daly and the strange woman who had come and sat in the kitchen as though it were completely natural, and her father’s changed manner towards her, and the doctor and the priest referring to her brother all the time as “they”, as though he weren’t a single baby but one of a group, all identical: the presence in their house of a priest who behaved as though he were entitled to exercise some authority was also a novelty. Her father was not a practising Catholic, and while he didn’t actively discourage priests from visiting, he liked them to know that their presence was on his terms. If they were going to drink his whiskey, he would say, then he had every right to give them his opinion of the papacy, or of the role they had played in keeping people poor and ignorant.

Now, just as strange as anything else was the sudden silence in the room and Nora feeling instantly at a loss. Something seemed to be required of her and she didn’t know what. It didn’t seem that her mother was in a position to offer her a direction on how to behave in these changed circumstances. Tentatively, she walked along the side of the bed towards her mother and the baby. She wondered whether she ought to kiss her mother, but felt estranged and awkward. Instead she said, ‘Will I look at the baby?’

‘If you want,’ said her mother indifferently.

Nora peered into the cradle and all her anxieties suddenly evaporated. He was, after all, just a baby, not unlike any other that she had seen. No, that wasn’t quite true since he had long, fair hair – hair the same colour as her mother’s, just as she had her father’s black hair – and all the other babies she had seen had been bald. She bent over and touched his hair and was surprised to find it silky, not unlike her own when it had been washed. As she touched him, he stirred and opened his eyes. She saw that they slanted up at the corners, but they were large and a deep, deep navy blue, unlike any other eye colour in the world.

She looked up and said, ‘He’s really pretty,’ but her mother’s face was blank and she turned her head as soon as their eyes met and sank back into the pillows.

There followed another of the periods of blank time that had punctuated the day – a day that had alternated strangely between boredom and fear. Normally there was a routine, and wherever she was in the day, Nora knew what would happen next. But now, although it was long dark, she hadn’t had her bath, or tea, or a story, and as far as she could tell, her parents had forgotten that she had come to depend on this clear sequence of events. She kept her position by the baby, who was silent in a way that, from her limited experience of babies, she hadn’t expected. Once or twice there was a slight stirring and he seemed on the point of crying. His mouth opened, but no sound came out, as though it were too much effort for him. She wondered whether he needed to be fed. She crept round to get a better view of her mother, who she assumed was sleeping, but she found her as before, staring blankly at the wall ahead. If she was aware of Nora, she gave no sign.

It was some time after the doctor and priest had left before her father came to the bedroom door, where he stood, as if reluctant to enter. ‘Will you have something to eat, Bernie?’

‘I couldn’t swallow a thing.’

‘A cup of tea?’

‘I’ve drunk so much tea today that I don’t think I’ll be able to get the taste out of my mouth again.’

‘Right you are, then,’ he said, clutching the door handle as if to retreat.

‘Gerald, will you wait a minute? There’s something I want to talk to you about.’

‘Can’t it wait?’

‘Please.’

Gerald stepped into the room, closed the door behind him and leaned against it.

‘Won’t you sit down?’

‘I’m right enough like this.’

Bernie shifted herself into a sitting position, wincing slightly from the stitches. ‘We should decide what we’ll call him.’

‘Not now, Bernie. I can’t believe there’s any urgency. There are families of ten in this very town where the last ones had to wait weeks for a name, until their parents could summon up the energy.’

‘There may not be any urgency for you but they’ve been at me all the time – the nurses, the doctors, Father McCaffrey, and it will be the same with the midwives tomorrow. I’d just like them to leave me be, with all their talk about bonding and giving him a name so that he’s part of the family.’

Gerald sighed deeply. ‘Well, if you’ve got any ideas, you just go ahead. It’s all the same to me.’

‘Father McCaffrey wondered about Felix.’

‘Isn’t that the name of the cat in the cartoon? I didn’t realise that the old boy had a sense of humour. Well, I’ll just take a wee look and see whether I think it suits him.’ He walked over to the cradle and peered inside without touching the baby. ‘What do you think, Nora? Do you think your brother looks like a Felix?’

‘I don’t know what a Felix looks like.’

‘That’s very good,’ said Gerald, laughing grimly. ‘I would say that makes it an appropriate name.’

‘Father McCaffrey says it means “happy”,’ said Bernie wearily. ‘He says it will help us if we think of him in that way.’

‘Does he now? Well, at least he’s consistent. Priests are experts at convincing themselves that what they want to believe is actually there, only they call it God. Maybe he’d like to take him off our hands and try it out for himself, since he’s had so much practice.’

‘We have to live here, Gerald. We have to do what’s expected of us.’

‘Go ahead, then, name him Felix,’ said Gerald, on his way to the door.

‘He says it’s Greek,’ said Bernie, delaying her husband’s departure. ‘He said it might appeal to you, as a man of learning. I said that we’d thought of giving him an Irish name and we’d talked about Sean and Liam if it was a boy.’ Her voice caught on the memory of that distant, hopeful time before she had given birth, since when the world had changed for ever. Two fat tears made their way slowly down her cheeks, but she continued speaking, although her voice was thicker: ‘He said it was only a suggestion, and that an Irish name might be even better. He said it would make him part of the community.’

‘No, we’ll call him Felix,’ said Gerald. ‘He doesn’t look like an Irishman to me.’

With that he was gone. Apart from asking Nora’s opinion of the name, he had scarcely looked at her. After he’d gone, her mother lapsed back into her torpor. Nora could scarcely stay in her parents’ room all night, so she got up and crept to the door. Before she left the room she glanced back and saw that, although her mother was motionless, she was still crying. She had never seen her like that before. Usually she cried because she was angry, or feeling neglected, and the crying was accompanied by raised voices, but this time it was silent and she let her tears flow without drying them. It was almost as though she didn’t know what was happening.

It didn’t seem right to disturb her, so Nora slipped out of the room and into the lounge, where her father was sitting in his special armchair with a glass of whiskey in his hand, watching the television. It seemed to be the news. As she stood there, the face of Mrs Thatcher flashed on to the screen. As the Prime Minister started to speak, Gerald said, with unusual vehemence, ‘The woman’s a bloody animal.’ Immediately Nora remembered that for a few hours that morning she had thought her new brother was a gerbil, and she felt again the terrible dread that had lasted until she saw him. Then, in her mother’s bedroom, her father had made a joke about Felix the cat, which she didn’t understand. She looked again at Mrs Thatcher and wondered what her father saw in this middle-aged English woman that she couldn’t see. The idea that a person could be an animal was so shocking to Nora that her mind recoiled from it. Nora knew that her father didn’t like Mrs Thatcher, and that she shouldn’t like her either because of what she had done to the Irish, but she had never heard him call her an animal before. She placed herself in his line of vision and said, ‘Will I go to bed now?’

Barely glancing at her he said, ‘Does your mother need you any more?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Then you might as well go to bed.’