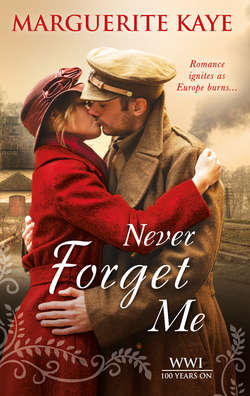

Читать книгу Never Forget Me - Marguerite Kaye - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter One

Argyll, Scotland—October 1914

Corporal Geraint Cassell, late of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and currently seconded to the Army Service Corps, gazed out of the window as the staff car swept up the impressive driveway. There was something about the quality of light, the way it filtered through the battleship-grey clouds, casting a soft haze over everything, that made him think of home. The picturesque villages they had skirted on the journey north, though, looked nothing like the gritty Welsh mining village in which he had been raised, where the narrow houses huddled into the valley, their tiny windows looking blindly out onto the road, which rose steeply towards the pit head and the winding wheel that dominated the skyline. In contrast, the whitewashed Highland cottages seemed like something out of a child’s fairy tale.

Private Jamieson pulled the car to a halt in front of Glen Massan House. Geraint surveyed the place with a jaundiced eye. It was more like a castle than a house. Built in the Scots’ baronial style, he had gleaned from the requisition orders, it sat on a promontory with a commanding view over Loch Massan. A large tower five stories high with crenellated battlements bolstered one side of the grey granite building, while the main body of the house, with its steep-pitched roofs and its plethora of smaller, conical towers, seemed to have been added higgledy-piggledy. The result was strangely attractive. It was easy to imagine generations of Carmichael lairds striding out from that massive portico in their plaids, hounds yelping at their heels, to go off on a stag hunt or whatever it was that Scottish lairds did.

Generations of crofters and serfs had no doubt dutifully served their lord and master here, working the land for a pittance and shivering in their thatched cottages, Geraint reminded himself. Whatever this war brought, one thing was certain, it was the end of the line for people like Lord Carmichael and his privileged family.

The war would see the end of the line, too, with a bit of luck, for the ‘Old Contemptibles’ like Colonel Aitchison, whose ilk were bumbling about with General French over on the Western Front. Geraint belatedly turned and saluted as his so-called superior officer finally stumbled out of the staff car juggling gloves, hat and swagger stick. No doubt the Carmichaels of Glen Massan House would resent being evicted from their pretty Highland castle, but Geraint refused to feel sorry for them.

* * *

‘I simply can’t comprehend why the army wants our home. Why Glen Massan?’

The question was rhetorical, though Lady Elizabeth Carmichael had asked it repeatedly since the requisition order had arrived. Her daughter, Flora, looked up from the newspaper in which she had been reading the first encouraging reports of the battle being waged at Ypres. ‘Perhaps it really will be over by Christmas,’ she said, ‘in which case, we will only have to decamp to the Lodge for a few months.’

‘A few months! The place is tiny. There are only three bedrooms.’

‘Then Robbie will have to bunk with Alex the next time he comes up from London,’ Lord Carmichael said patiently.

‘But that means you and I will have to share a bedroom.’

‘We are married, Elizabeth, and there is a war on, in case either fact had escaped your attention. It is up to all of us to make sacrifices.’

Lady Carmichael took a sip of tea. ‘Do you really think it will be over by Christmas as they say?’ she asked her daughter.

Flora’s opinion was so rarely consulted that for a moment she was quite taken aback. ‘I don’t know,’ she answered simply. ‘If the newspapers are to be believed...’ She halted mid-sentence, because the growing casualty lists and the claims of imminent victory seemed to her at odds. The reports in the papers were unrelentingly cheerful, full of praise for the bravery of the men who went ‘over the top’. At times, they made life in the trenches sound like some sort of Boy Scout camp. In the first weeks, Flora had been as enthusiastic as everyone else, but now that men from both sides were dying in unimaginable numbers, she was beginning to have the most unpatriotic doubts about the ability of those in charge to do their job.

Not that she would dream of saying so in front of her parents, who considered any talk of casualties defeatist. Leaning across the table to clasp her mother’s hand, she smiled weakly. ‘Perhaps it will be over soon. I sincerely hope so.’

‘It is selfish of me, but you know how much your brother Alex wishes to join the older boys from his school who have already enlisted.’

‘Alex is only seventeen,’ the laird said pointedly. ‘He is at no risk.’

But Robbie, Flora’s other brother, who was twenty-five and currently running his wine-importing business from London, certainly was. The laird did not say so, but it was obvious to her that all three of them were thinking that Robbie’s joining up was a distinct possibility. ‘It’s almost a full year before Alex is eligible to enlist,’ Flora said, trying to sound more reassuring than she felt. ‘If it’s not over by Christmas then it certainly will be long before then.’

‘I hear that our ghillie’s son, Peter McNair, is talking of joining up,’ Lady Carmichael said. ‘Mrs Watson from the village shop told me that they are attempting to form one of those units Kitchener made such a fuss about.’

‘A Pal’s Battalion,’ the laird said dismissively. ‘Foolish name, foolish idea. This is a small community, we can ill afford to lose significant numbers of men.’

‘I quite agree,’ Lady Carmichael said. ‘Our local young men would be better served tending to the fields. Not that I would dream of saying so outside these four walls,’ she added hastily. ‘We are at war after all. Though why that requires us to be cast out of house and home...’

‘We shall know soon enough,’ her husband retorted sharply. ‘The army are due this morning.’

Lady Carmichael sighed. Weak autumn sunshine filtered through the voile curtains draped over the two long windows of the dining room, bathing her in its unforgiving light. Her mother’s stern beauty had held up remarkably well, Flora thought. They were so unalike, mother and daughter, sharing little but the same grey-blue eye colour. She would have liked to possess some of her mother’s curves, but she had inherited her father’s physique, being tall and slim.

‘Would you like me to deal with the army chaps?’ she asked, thinking that at least she might spare both her parents and the unsuspecting officer in charge.

Lady Carmichael, however, looked horrified. ‘Don’t be ridiculous. You cannot possibly take on such a task, it would be quite beyond you.’

‘I am twenty-three years old, and since you trust me with little more than flower arranging, I don’t see how you can have any idea what I am capable of.’

‘Flora!’

Lady Carmichael looked scandalised by this unexpected riposte. Flora was rather surprised at herself, for though she often disagreed with her mother, she rarely allowed herself to say so. ‘I beg your pardon,’ she said, feeling not at all contrite, ‘but I would very much like to feel useful, and I wished to spare you what can only be a painful process.’

‘Flora is quite right,’ the laird said, coming unexpectedly to her aid. ‘It will be difficult for us to relinquish the house. Perhaps we should delegate the task to her after all.’

‘Father, thank you.’

‘Andrew! You cannot mean that. Why Flora is— She has no experience at all. And besides, think of the proprieties. All those rough young soldiers.’

‘For goodness’ sake, Elizabeth, those rough young soldiers are British Tommies, whom I’m sure will treat both the house and our daughter with respect. Whatever the army’s intentions are for Glen Massan, it will require our home to be stripped of its contents. I am trying to spare you the trauma of witnessing that, and frankly I have little stomach for the sight, either.’ Lord Carmichael patted his wife’s hand. ‘Best you concentrate your energies on making the Lodge comfortable for us, my dear. If Flora makes a hash of things, I can always step in.’

It was not quite the wholehearted endorsement she would have liked, but it was nevertheless more than she had hoped. What was more, loathe as she was to admit it, her father was entitled to his reservations. ‘I shall do my best to ensure it doesn’t come to that,’ Flora said, pleased to hear that she sounded considerably more confident than she felt. It was wrong to think that any good could come from this horrible war, but it would be equally wrong for her not to seize the opportunity it provided to prove herself.

Outside, a horn honked, gravel scrunched and in the distance, a low rumble could be heard growing ever nearer. Flora ran to the window. ‘Speak of the devil. It’s an army staff car. A Crossley I think, Father. Alex would know.’ She gazed out in amazement at the convoy of dusty vehicles following behind the gleaming motor car. ‘Goodness, there are so many of them. Where will they sleep?’

‘Certainly not in the house. At least—I suppose we could accommodate some of the officers,’ Lady Carmichael said unconvincingly.

‘My dear,’ the laird said, ‘this will be their house very soon. They will sleep where they choose. In the meantime, I expect they will put up tents.’

‘On the lawn! In full sight! Andrew, you cannot...’

‘Elizabeth, you must allow Flora to worry about the details.’

As truck after truck pulled to a stuttering halt and what seemed to Flora like a whole battalion of men began to descend, she struggled not to feel quite overwhelmed.

‘It is like an invasion,’ her mother said in horror, and Flora couldn’t help but think that she was right.

The driver of the staff car pulled open a door and a polished, booted foot appeared. Flora straightened her back and took a deep breath. These are our brave boys, she reminded herself. ‘I think we’d better go and see what we can do to assist them.’

Her father gripped her shoulder. ‘Bravo,’ he said softly. ‘Get your mother to the Lodge first. Join me as soon as you can.’

Feeling anything but brave, Flora watched him leave before turning to her mother and pasting on a smile. ‘Well, it looks as though the war has arrived in Glen Massan.’