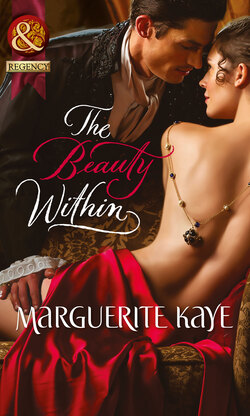

Читать книгу The Beauty Within - Marguerite Kaye - Страница 10

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеGiovanni leapt down from the gig as it drew to a halt in front of Killellan Manor, the country estate of the Armstrong family, airily dismissing the waiting footman’s offer to escort him to the door. He had travelled to Sussex on the mail, which had been met at the nearest posting inn by Lord Armstrong’s coachman. It was a cold but clear day, the clouds scudding across the pale blue sky of early spring, encouraged by the brisk March breeze. Pulling his greatcoat more tightly around himself, he stamped his feet in an effort to stimulate the circulation. There were many things about England he admired, but the weather was not one of them.

Lord Armstrong’s impressive residence was constructed of grey sandstone. Palladian in style, with the main four-storey building flanked by two wings, the façade which fronted on to the carriage way was marred, in Giovanni’s view, by the unnecessary addition of a much later semicircular portico. Enclosed by the high hedges into which the gates were set, the house looked gloomy and rather forbidding.

Wishing to stretch his legs after the long journey before announcing his presence, Giovanni followed the main path past a high-walled garden and the stable buildings to discover a prospect at the front of the house altogether different and much more pleasing to the eye. Here, manicured lawns edged with bright clumps of daffodils and narcissi stretched down, via a set of wide and shallow stone steps, to a stream which burbled along a pebbled river bed towards a watermill. On the far side of the river, the vista was of gently rolling meadows neatly divided by hedgerows. Despite the fact that the rustic bridge looked rather suspiciously too rustic, he couldn’t help but be entranced by this quintessentially English landscape.

‘It is a perfect example of what the poet, Mr Blake, calls England’s green and pleasant land, is it not?’

Giovanni started, for the words came from someone standing immediately behind him. The rush of the water over the pebbles had disguised her approach. ‘Lady Cressida. I was thinking almost exactly that, though I am not familiar with the poet, I’m afraid. Unless—could it be William Blake, the artist?’

‘He is more known for his verse than his art.’

‘That will change. I have seen some of his paintings. They are …’ Giovanni struggled to find an appropriate English word to describe the fantastical drawings and watercolours which seemed to explode out of the paper. ‘Extraordinary,’ he settled on finally and most unsatisfactorily. ‘I find them beautiful, but most certainly they would fail your mathematical criteria.’

‘And this?’ She waved at the landscape. ‘Would you consider this beautiful?’

‘I suspect your father has invested rather a lot of money to ensure that it is. That bridge, it cannot possibly be as old as it appears.’

‘There is also a little artfully ruined folly in the grounds, and you are quite correct, neither are older than I am.’

It had been more than two weeks since their first meeting in London. In the interval, Giovanni had replayed their conversation several times in his head, and that almost-but-not-quite kiss too. It had been a foolish act to take such a liberty with the daughter of the man who was paying his commission, and a man of such palpable influence too. He couldn’t understand why he had been so cavalier. Attempting to recreate Lady Cressida feature by feature using charcoal on paper had proved entirely unsatisfactory. He had been unable to capture the elusive quality that had piqued his interest. Now, as she stood before him, the sun shining directly behind her, making a halo of her wild curls, the dark shadows under her startlingly blue eyes, the faintest trace of a frown drawing her brows together giving her a delicate, bruised look, he could see that it was nothing to do with her features but something more complex which drew him to her. It puzzled him, until he realised that her allure was quite basic. He wanted to capture that ambiguity of hers in oils.

‘You look tired,’ Giovanni said, speaking his thoughts aloud.

‘My brothers are—energetic,’ Cressie replied. Exhausting would be more accurate, but that would sound defeatist. Two weeks of shepherding four small boys intent on making mischief had taken their toll—for the twins, though not formally included in her lessons, insisted on being with their brothers at all times. Until they had become her responsibility, she had been dismissive of Bella’s complaints that the boys wore her down to the bone. They were mere children—all they required was sufficient mental stimulation and exercise, Cressie had thought. She realised now that her contempt had been founded on blissful ignorance.

Her evenings had therefore been spent making a guilty effort to become better acquainted with a stepmother who made it plain that her company was welcome only in the absence of any other, for Cordelia had hastened to London the day after Cressie’s arrival at Killellan, fearful that either Lord Armstrong or Aunt Sophia might change their minds about her impending coming-out season. Cressie was alone for the first time in the house without any of her sisters for company. She was becoming short-tempered and grumpy with the boys, which in turn made her annoyed with herself, for she wanted to like her brothers as well as love them. She tried not to blame them for the lack of discipline which made them unruly to a fault. Every morning she told herself it was just a matter of trying harder. ‘I fear I rather underestimated the effort it takes to keep such active minds and bodies occupied,’ she said, smiling wanly at the portrait painter. ‘Still, I believe teaching will bring its own reward. At least—I hope it will.’

Giovanni looked sceptical. ‘You should demand fair payment from your father. I think you would be amply rewarded if you did so, if only by his reaction.’

‘Goodness, he would be appalled,’ Cressie exclaimed. ‘The fact is I’m doing this for my own reasons, not merely to accommodate my father.’

‘And those reasons are?’

‘No concern of yours, Signor de Matteo. You do not like my father much, do you?’

‘He reminds me of someone I dislike very much.’

‘Who?’

‘That is no concern of yours, Lady Cressida.’

‘Touché, signor.’

‘You do not much like your father either, do you?’

‘You ought not to have to ask such a question. And I ought to be able to answer positively.’ Cressie grimaced. ‘He enjoys making things difficult for me. And I him, if I am honest.’

The mixture of guilt and amusement on her face was endearing. The wind whipped a long lock of hair across her face, and without thinking, Giovanni made to brush it away at the same time as she did. His gloved hand covered her fingers. The contact jolted him into awareness, just as when he had kissed her hand, and the arrested look in her eyes made him aware that she felt it too. Her eyes widened. She shivered. The sun dazzled her eyes, and the moment was gone.

Cressie wrapped her arms around herself as the wind caught her again. She had come out without even a wrap. ‘We should go inside,’ she said, turning away, thrown off balance not just by the tangle of her gown, which the breeze had blown around her legs, but by her own reaction to Giovanni de Matteo’s touch. She was not usually a tactile person, but he made her acutely conscious of her body, and his. She did not want him to see the effect he had on her, though no doubt he had the same effect on every female he encountered. ‘I should take you to meet my brothers now. My stepmother does not like me to leave them with the nursery maid for too long.’

‘Let them wait a little longer. I would like to see something of the house in order to find a suitable place to set up my easel. Lady Armstrong cannot object to you assisting me, can she? And you, Lady Cressida, you cannot object to my company over your brothers’, even if we seem to disagree on almost every subject.’

She couldn’t help laughing, and her laughter dispelled her awkwardness. ‘After the morning I have had in the schoolroom I assure you I would take almost any company over my brothers’, even yours. I most certainly do not object. Come, follow me.’

The portrait gallery ran the full length of the second floor. Light streamed in through windows which looked out over the formal gardens. The paintings were hung in strict ancestral sequence on the long wall opposite. ‘I thought you might wish to set up your studio here,’ Cressie said.

Giovanni nodded approvingly. ‘The light is good.’

‘The yellow drawing room and music room are through these doors, but neither are much used for Bella, my stepmother, prefers the smaller salon downstairs, and since Cassie—Cassandra, my second sister—left home some years ago, I doubt anyone has touched the pianoforte, so you will not be disturbed.’

‘Except by my subjects.’

‘True. I do not know how you prefer to work, whether they must sit still for hours on end, but …’

‘That would be to expect the impossible, and in any event not necessary.’

‘That is a relief. I was wondering whether I would have to resort to tying them to their chairs. Actually, I confess that I have been wondering whether I must resort to doing just that in order to keep them at their lessons. I had hoped that my primer—’ Cressie broke off, tugging at the knot of hair which she had managed to tangle around her index finger, and forced herself to smile brightly. ‘My travails as a teacher cannot possibly be of interest to you, signor. Let us look at the paintings.’

Though her determination to shoulder the blame for her brothers’ failings intrigued him, there was a note in her voice that warned Giovanni off from pursuing the subject. He allowed her to lead him from portrait to portrait, listening while she unravelled for him the complex and many-branched Armstrong family tree, enjoying the cadence of her voice, taking the opportunity to study, not the canvases, but her face as she talked animatedly about the various family members. There was something deep within her that he longed to draw out, to capture. He was certain that beneath the veneer of scientific detachment and tightly held emotions, there was passion. In short, she would make a fascinating subject.

He must find a way of painting her portrait. Not one of his idealised studies, but something with some veracity. He had thought the desire to paint from the heart had died in him, but it seemed it had merely been lying dormant. Lady Cressida Armstrong, of all unlikely people, had awakened his muse.

But tantalising glimpses, mere impressions of her hidden self would not suffice. A certain level of intimacy would be required. In order to paint her he needed to know her—her heart and her mind, though most definitely not her body. Those days were past.

And yet, he could not take his eyes from her body. As she moved to the next painting he noticed how the sunlight, dancing in through the leaded panes in the long windows, framed her dress, which was white cotton, simply made, with a high round neck. The sleeves were wide at the shoulder as was the fashion, tapering down to the wrists, the hem tucked and trimmed with cotton lace. With a draughtsman’s eye he noted approvingly how the cut of the gown enhanced her figure—the neat waist, the fullness of her breasts, the curve of her hips. In this light, he could clearly see the shape of her legs outlined against her petticoats. One of her stockings was wrinkled at the ankle. The sash at her waist was tied in a lopsided knot rather than a bow, and the top-most button at her neck was undone. She employed no maid, Giovanni surmised, and she had certainly not taken the time to inspect herself in the mirror. Haste or indifference? Both, he reckoned, though rather more of the latter.

He followed her to the next painting, but the pleasing roundedness of her fondoschiena, the tantalising shape of her legs, distracted him. He wanted to smooth out the wrinkle in her stocking. There was something about the fragile bones in a woman’s ankle that he had always found erotic. And the swell of a calf. The softness of the flesh at the top of a woman’s thighs. He had tasted just enough of her lips to be able to imagine how yielding the rest of her would be.

Giovanni cursed softly under his breath. Sex and art. The desire for both had been latent until he met her. Painting her was a possibility, but as for the other—he was perfectly content in his celibate state, free of bodily needs and the needs of other bodies.

‘This is Lady Sophia, my father’s sister,’ Lady Cressida was saying. ‘My Aunt Sophia is—you know, I don’t think you’ve been listening to a word I’ve said.’

They were standing in front of the portrait of an austere woman who bore a remarkable resemblance to a camel suffering from a severe case of wind. ‘Gainsborough,’ Giovanni said, recognising the style immediately. ‘Your aunt, you were saying.’

‘What were you really thinking about?’

‘Is there a painting of you among the collection?’

‘Only one, in a group portrait with my sisters.’

‘Show me.’

The painting had been hung between two doors, in the worst of the light. Lawrence, though not one of his best. There were five girls, the eldest two seated at a sewing table, the younger three at their feet, playing with reels of cotton. ‘That is Celia,’ Lady Cressida said, pointing to the eldest, a slim young woman with a serious expression and a protective hand on the head of the youngest child. ‘Beside her is Cassie. As you can see, she is the beauty of the family. Cordelia, my youngest sister who makes her come out this Season, is very like her. Caroline is beside her, and that is me, the odd one out.’

Giovanni nodded. ‘You certainly have very different colouring. What age were you when this was painted?’

‘I don’t know, eleven or twelve, I think. It was before Celia married and left home.’

‘I am surprised that your mother is not in this painting. Lawrence would usually have included the mother in such a composition.’

‘She died not long after Cordelia was born. Celia was more of a mother to us than anyone.’ Lady Cressida’s voice was wistful as she reached out to touch her sister’s image. ‘I haven’t seen her for almost ten years. Nor Cassie, for eight.’

‘Surely they must visit, or you them?’

‘It is a long way to Arabia, signor.’ Obviously sensing his confusion, Lady Cressida hastened to explain. ‘Celia married one of my father’s diplomatic protégés. They were in Arabia, sent on a mission by the British Ambassador to Egypt, when Celia’s husband was murdered by rebel tribesmen. I remember it so well, the news being broken to us here at Killellan. We were told that Celia was being held captive in a harem. My father and Cassie and Aunt Sophia went to Arabia to rescue her only to discover that she didn’t want to be rescued. Fortunately for Celia, it turned out that her desert prince was hugely influential and fantastically rich, so my father was happy to hand her over.’

‘And your other sister—Cassie, did you say?’

‘When she narrowly escaped a most unfortunate connection with a poet, our father packed her off in disgrace to stay with Celia. He should have known that Cassie, a born romantic, would tumble head over heels in love with the exotic East. When he found out that he had lost a second daughter to a desert prince he was furious. But this prince too turned out to have excellent diplomatic connections and was also suitably generous with his riches, so my father magnanimously decided to be reconciled to the idea.’

‘Such a colourful history for such a very English family,’ Giovanni said drily.

She laughed. ‘Indeed! My father decided two sheikhs, no matter how influential, was more than sufficient for any family. I think he fears if any of us visit them, the same fate would befall us, so we must content ourselves with exchanging letters.’

‘And are they happy, your sisters?’

‘Oh yes, blissfully. They have families of their own now too.’ Lady Cressida gazed lovingly at the portrait. ‘It is the only thing which makes it bearable, knowing how happy they are. I miss them terribly.’

‘But you are not quite alone. You have your stepmother.’

‘It is clear you have not been introduced to Bella. My father married her not long after Celia’s wedding. I think he assumed Bella would take on Celia’s role in looking after us three younger girls as well as providing him with an heir but Bella—well, Bella saw things differently. And once James was born, so too did Papa. His only interest is his male heirs.’

‘Sadly, that is the way of the world, Lady Cressida.’

‘Cressie. Please call me Cressie, for no one else here does, now Caro has married and Cordelia has gone to London. I am the last of the Armstrong sisters,’ she said with a sad little smile. ‘I think you have heard more than enough of my family history for one day.’

‘It seems to me a shame that there are no other portraits of you. May I ask—would you—I would like to paint you, Lady—Cressie.’

‘Paint me! Why on earth would you want to do that?’

Her expression almost made him laugh, but the evidence it gave him of her lack of self-worth made him angry. ‘An exercise in mathematics,’ Giovanni replied, hitting upon an inspired idea. ‘I will paint one portrait to your rules, and I will paint another to mine.’

‘Two portraits!’

‘Si. Two.’ An idealised Lady Cressida and the real one. For the first time in years, Giovanni felt the unmistakable tingle of certainty. Ambition long subdued began to stir. Though he had no idea as yet what this second portrait would be, he knew at least it would be his. Painted from the heart. ‘Two,’ Giovanni repeated firmly. ‘Thesis and antithesis. What better way for me to provide you with the proof you need for your theory—or the evidence which contradicts it?’ he added provocatively, and quite deliberately.

‘Thesis and antithesis.’ She nodded solemnly. ‘An interesting concept, but I don’t have the wherewithal to be able to pay you a fee.’

‘This is not a commission. It is an experiment.’

‘An experiment.’

Her smile informed him that he had chosen exactly the right form of words. ‘You understand, it will require us to spend considerable time alone together. I cannot work with any distractions or interruptions,’ he added hastily, realising how ambiguous this sounded. ‘You will need to find a way of ridding yourself of your charges for a time.’

‘Would that I could do so altogether.’ Cressie put her hand over her mouth. ‘I did not mean that, of course. I will find a way, but I think it would be prudent if we keep our experiment between ourselves, signor.’ She grinned. ‘You and I know that we are conducting research in the name of science, but I do not think Bella would view our being locked away alone together with only an easel for company in quite the same light.’

As Bella Frobisher, Lady Armstrong had been a curvaceous young woman when she first met her future husband, with what his sister, Lady Sophia, called ‘fine child-bearing hips’. Those hips had now borne four children, all of them lusty boys, and were, like the rest of Bella’s body, looking rather the worse for wear. A naturally indolent temperament, combined with a spouse who made little attempt to hide his indifference to every aspect of her save her ability to breed, led Bella to indulge her sweet tooth to the full. Her curves were now ample enough to undulate, rippling under her gowns in a most disconcerting manner, her condition having forced her to abandon her corsets. At just five-and-thirty, she looked at least ten years older, dressed as she was in a voluminous cherry-red afternoon dress trimmed with quantities of frothy lace which did nothing for her pale complexion. A pretty face with a pair of sparkling brown eyes was just about visible sunk amid an expanse of fat.

Though she had never aspired to being a wit, Bella had been happy to be labelled vivacious, and had always been extremely sociable until her husband made it clear that her lack of political nous made her something of a liability. He summarily replaced her at the head of his political table with his sister and, having made sure that she was impregnated, consigned his wife to the country. Here, Bella had remained, popping out healthy Armstrong boys at regular intervals, taking pleasure in her sons but in very little else. Though she knew it would displease her husband, she longed for this next child to be a daughter, the consolation prize she surely deserved, who would provide her mama with the affection she craved.

Disappointed from a very early stage in her marriage, unable to express her disappointment to the man responsible, Bella had turned her ire instead on his daughters, who made it very easy for her to do so since they made it all too obvious that they thought her a usurper. Her malice had become a habit she did not even contemplate breaking. Pregnant, bloated, lonely and bored, it was hardly surprising, then, that Giovanni, his breathtaking masculine beauty enhanced by the austerity of his black attire, would appear to her like a gift from the gods she thought had abandoned her.

‘Lady Armstrong, it is an honour,’ he said, bowing over her dimpled and be-ringed hand as she lay on the chaise-longue, ‘and a pleasure.’

Bella simpered breathlessly. She had never in all her days seen such a divine specimen of manhood. ‘I can tell from your delightful accent that you are Italian.’

‘Tuscan,’ Cressie said tersely, unaccountably annoyed by the extraordinary effect Giovanni was having on her stepmother. She sat down in a chair opposite and gazed pointedly at Lady Armstrong’s prostrate form. ‘Are you feeling poorly again? Perhaps we should leave you to take tea alone?’

Flushing, Bella pushed aside the soft cashmere scarf which covered her knees, and struggled upright. ‘Thank you, Cressida. I am quite well enough to pour Signor di Matteo a cup of tea. Milk or lemon, signor? Neither? Oh well, of course I suppose you Italians do not drink much tea. An English habit I confess I myself am very fond of. Cake? Well then, if you do not, I shall have to eat your slice else cook will be mortally offended, for Cressida, you know, has not a sweet tooth. Perhaps if she did, her temperament might improve somewhat. My stepdaughter is very serious, as you will no doubt have gathered by now, signor. Cake is far too frivolous a thing for Cressida to enjoy. You know, of course, that she is presently acting governess to two of my sons? James and Harry. You will be wishing to know more about them, I dare say, if you are to do justice to my angels.’ Finally stopping for breath, Bella beamed and ingested the greater part of a wedge of jam sponge.

‘Lord Armstrong informs me that his sons are charming,’ Giovanni said into the silence which was broken only by his hostess’s munching. She nodded and inhaled another inch or so of cake. Fascinated by the way she managed to consume so much into such a comparatively small mouth, he was momentarily at a loss.

Brushing the crumbs from her fingers, Bella launched once more into speech, this time a eulogy on the many and manifold charms of her dear boys. ‘They are so very fond of their little jokes too,’ she trilled. ‘Cressida claims they lack discipline, but I tell her that it is a question of respect.’ Bella cast a malicious smile at her stepdaughter. ‘One cannot force-feed such intelligent children a lot of boring facts. Such a method of teaching is all very well for little girls, most likely, but with boys as lively as mine—well, I am not one to criticise, but I do think it was a mistake, not hiring a qualified governess to replace dear Miss Meacham.’

‘Dear Miss Meacham left because she could no longer tolerate my brothers’ so-called liveliness,’ Cressie interjected.

‘Oh, nonsense. Why must you always put such a negative slant on everything your brothers do? Miss Meacham left because she felt she was not up to the job of tutoring such clever children. “I wish fervently they get what they deserve” is what she said to me when she left, and I heartily agree. I don’t know what your father was thinking of, to be perfectly honest, entrusting you with such a role, Cressida. Though perhaps it is more of a question of not knowing what role to assign you, since you are plainly unsuited to play the wife. After—how many years is it now, since I launched you?’

‘Six.’

Bella shook her head at Giovanni. ‘Six years, and despite the best efforts of myself and her father, she has not been able to bring a single man up to scratch,’ she said sweetly. ‘I am not one to boast, but I had Caroline off my hands with very little fuss, and I have no doubt that Cordelia will go off even more quickly. You have not met Cressida’s sisters, but sadly she has none of their looks. Even Celia, the eldest, you know, who lives in Arabia, has her charms, though it was always Cassandra who was the acknowledged beauty. I suppose one plain sister out of five is to be expected. If only she were not such a blue-stocking, I really do believe I could have done something with her.’ Bella shrugged and smiled sweetly again at Giovanni. ‘But she scared them all off.’

Realising that she was in danger of looking like a petulant child, Cressie tried not to glower. The words so closely echoed her father’s that she was for a moment convinced he and Bella were conspiring to belittle her. Though Bella had said nothing new, nor indeed anything which Cressie had not already blurted out to Giovanni upon their first meeting, it was embarrassing to have to listen to her character being dissected in such a way. So much for all her attempts to think more kindly of her stepmother. As to what Giovanni must be making of Bella’s shocking manners, it didn’t bear thinking about.

She put down her tea cup with a crack, determined to turn the conversation to the matter of the portrait, but Bella, having refreshed herself with a cream horn, was not finished. ‘I remember now, there was a man your father and I thought might actually make a match of it with you. What was his name, Cressida? Fair hair, very reserved, a clever young man? You seemed quite taken with him. I remember saying to your father, she’ll surely reel this one in. In fact, as I recall, you actually told us he was going to call, but he never did. He took up a commission shortly after, now I come to think of it. Come now, you must remember him, for it is not as if you were crushed by suitors. Oh, what was his name?’

She could feel the flush creeping up her neck. Think cold, Cressie told herself. Ice. Snow. But it made no difference. Perspiration prickled in the small of her back. Having taught herself never to think of him, she had persuaded herself that Bella would have forgotten all about …

‘Giles!’ Bella exclaimed. ‘Giles Peyton.’

‘Bella, I’m sure that Signor di Matteo …’

‘He was actually quite presentable, once one got over his shyness. My lord thought it was a good match. He is not often wrong, but in this instance—the fact is, men do not like clever women. My husband’s first wife, Catherine, was reputed to be a bit of a blue-stocking, and look where it got her—five daughters, and dead before the last was out of swaddling. When he asked for my hand, Lord Armstrong told me that it was my being so very different from his first wife that appealed to him, which I thought was a lovely compliment. No, men do not like a clever woman. I am sure you agree, signor?’

Blithely helping herself to another pastry, Bella looked enquiringly at Giovanni, but before he could speak, Cressie got to her feet. ‘Signor di Matteo came here to paint my brothers’ portrait, Bella, not to discuss what he finds attractive in a woman.’ She swallowed hard. ‘I beg your pardon. And yours, Signor di Matteo. If you will excuse me, I have a headache, which is making me forget my manners.’

‘I hope you are not thinking of retiring to your room, Cressida. James and Harry …’

‘I am perfectly aware of my duties, thank you.’

‘If you wish to be excused from dinner, however, I am sure that Signor di Matteo and I can manage quite well without your company.’

‘I am sure that you can,’ Cressie muttered, wanting only to be gone before she lost her temper completely, or burst into tears. One or other, or more likely both, seemed imminent, and she was determined not to allow Bella the satisfaction of seeing just how upset she was.

But as she turned to go, Giovanni got to his feet. ‘I must inform you that you are mistaken on several counts, Lady Armstrong,’ he said curtly. ‘Firstly, there are many enlightened men, and I include myself among them, who enjoy the company of a clever woman very much. Secondly, I am afraid that I prefer to dine alone when I am working. If I may be excused, I would like the governess to introduce me to her charges.’

With a very Italian click of the heels and a very shallow bow, Giovanni took his leave, took Cressie’s arm in an extremely firm grip and marched them both out of the drawing room.

‘Lady Cressida. Cressie. Stop. The boys can wait a few moments longer. You are shaking.’ Opening a door at random, Giovanni led her into a small room, obviously no longer used for it was musty, the shutters drawn. ‘Here, sit down. I am not surprised that you are so upset. Your stepmother’s bitterness is exceeded only by her ability to devour cake.’

To his relief, Cressie laughed. ‘My sisters and I used to think her the wicked stepmother straight out of a fairytale. I don’t know why she hates us so—though my father is right, we have given her little cause to love us.’

‘Five daughters, all cleverer than she, and all far more attractive …’

‘Four of them more attractive.’

‘To continue the fairytale metaphor, why are you so determined to be the ugly sister?’

Cressie shrugged. ‘Because it’s true. Because it’s how it has always been. Do you have any brothers or sisters?’

‘No.’ At least, none who acknowledged him, which amounted to the same thing. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘I wondered if all families are the same. In mine, we were labelled by my father, pretty much from birth. Celia is the diplomat, Cassie the pretty one, Caroline the dutiful one who can always be depended upon, Cordelia the charming one and I—I am the plain one. Upon occasion I am classed the clever one, but believe me, my father uses that only as an insult. He doesn’t see beyond his labels, not even with Celia, whom he was most proud of because of her being so useful to him.’

Giovanni frowned. ‘But he does precisely the same to your stepmother. She is the brood mare—it is her only purpose. It is no wonder she feels inferior, and no wonder that she must disguise it by trying always to put you in your place. She is vulgar and brash and lonely, so she takes it out on you and your sisters. It is not excusable, but it is understandable.’

‘I hadn’t thought—oh, I don’t know, perhaps you are right, but I am not feeling particularly charitable towards her at the moment.’

Cressie had been worrying at a loose thread of skin on her pinkie, and now it had started to bleed. Without thinking, Giovanni lifted her hand and dabbed the blood with his fingertip before it could drip on to her gown. He put his finger to his lips and licked off the blood. She made no sound, made no move, only stared at him with those amazingly blue eyes. They reminded him of early morning fishing trips back home in his boyhood, the sea sparkling as his father’s boat rocked on the waves. The man he’d thought was his father.

With his hand around her slender wrist, his lips closed around her finger and he sucked gently. Sliding her finger slowly out of his mouth, he allowed his tongue to trail along her palm, let his lips caress the soft pad of her thumb. Desire, a bolt of blood thundered straight to his groin, taking him utterly by surprise. What was he doing?

He jumped to his feet, pulling the skirts of his coat around him to hide his all too obviously inflamed state. ‘I was just trying to prevent—I’m sorry, I should not have behaved so—inappropriately,’ he said tersely. She should have stopped him! Why had she not stopped him? Because for her, it meant nothing more than he had intended, an instinctive act of kindness to prevent her ruining her gown. And that was all it was. His arousal was merely instinct. He did not really desire her. Not at all.

‘It has been a long day,’ Giovanni said, forcing a cold little smile. ‘With your permission, I think I would like to meet my subjects now, and then I will set up my studio. I will dine there too, if you would be so good as to have some food sent up.’

‘You won’t change your mind and sup with us?’

She looked so forlorn that he almost surrendered. Giovanni shook his head decisively. ‘I told you, when I am working, distractions are unwelcome. I need to concentrate.’

‘Yes. Of course. I understand completely,’ Cressie said, getting to her feet. ‘Painting me would be a distraction too. We should abandon our little experiment.’

‘No!’ He caught her arm as she turned towards the door. ‘I want to paint you, Cressie. I need to paint you. To prove you wrong, I mean,’ he added. ‘To prove that painting is not merely a set of rules, that beauty is in the eye of the artist.’ He traced the shape of her face with his finger, from her furrowed brow, down the softness of her cheek to her chin. ‘You will help me do that, yes?’

She stared up at him, her eyes unreadable, and then surprised him with a twisted little smile. ‘Oh, I doubt very much that you’ll be able to make me beautiful. In fact, I shall do my very best to make sure you cannot, for you must know that my theory depends upon it.’