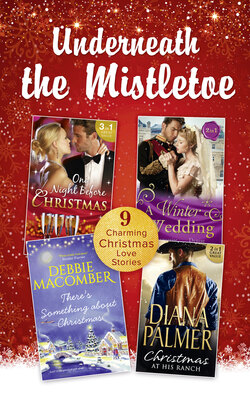

Читать книгу Underneath The Mistletoe Collection - Джанис Мейнард, Marguerite Kaye - Страница 18

ОглавлениеChapter Nine

Dear Madame Hera,

I have been married for eighteen months. I love my husband very much, and relations between us have always been most satisfactory, him being a perfect gentleman, if you understand my meaning. Indeed, I had no cause at all to complain, until that fateful tea party with my three closest friends several weeks ago. It was my birthday, and I must confess that along with tea, we did partake of some strong drink. Conversation turned to intimate matters. I was shocked to discover that my husband’s method of ministering to my needs was considered by my friends to be downright old-fashioned. Imagine my astonishment when they revealed the variety of other ways—well, I will draw a veil over that.

But the problem was that I could not. Draw a veil, that is. For my curiosity was aroused. Alas! Would that I had been content with what I had. When my husband came to my arms as usual on the following Saturday night, I tried to instruct him in one of these variations. It is true, I did fortify myself with a glass or two of his special port beforehand, but I rather think it was my inadequate instructions that were to blame. With hindsight, it is clear that his failure was not a cause for merriment, and that perhaps it was a mistake, after he had expended so much energy, to expect him to renew his efforts in the traditional way.

Now no amount of reassurance will convince my husband to repeat the attempt, despite the fact that I have obtained more complete instructions from my friends. Worse still, my husband assumes my desire to introduce an element of diversity into the bedchamber is actually implied criticism of his previous efforts, and has accused me of having simulated satisfaction in the past. As a result, my Saturday evenings are utterly bereft of marital comfort. What should I do?

Mrs J-A

September, 1840

Ainsley finished reading the letter aloud and looked enquiringly at Innes, seated at his desk and frowning as usual over the account books. ‘There, I told you I’d find something to distract you. What do you think she means when she said that her husband is a “perfect gentleman”? I’m assuming it is not that he gets to his feet when she enters a room.’

Innes pushed his papers away and came to join her on the large, overstuffed sofa that sat in front of the hearth. ‘She means that he ensures she is satisfied before he allows himself to complete his own pleasure.’

‘Oh.’ Ainsley grimaced, scanning the letter again. ‘I had no idea. I hate to think how many times Madame Hera has quite missed the point of some of her letters.’

‘What proportion of her correspondence do these sorts of problems form?’

‘That’s a good point.’ Ainsley brightened. ‘It is only since Felicity launched our personal answering service that they have grown. What do you think Madame Hera should advise Mrs J-A? Her poor husband is most likely imagining himself wholly inadequate. She will have to do something to reassure him.’

‘Not so long ago, Madame Hera would have been pretty certain that the problem lay with that poor husband.’

‘Not so long ago, Madame Hera wouldn’t have had an inkling as to what Mrs J-A meant by variety,’ Ainsley said drily, ‘and she would most certainly never have believed that it was acceptable for a woman to make actual requests. Though perhaps it is not, in general, acceptable at all. I have no idea how other men feel about it. Are you an exception?’

She looked expectantly at Innes, who laughed. ‘I have no idea, but I doubt it.’

‘I do feel it’s a shame that so many women know so little about the variations, as Mrs J-A calls them.’

‘Because variety really is the spice of life?’

He was teasing her. She felt the now-familiar tingle make itself known, but refused to be drawn. ‘Because it seems wrong that only men do,’ Ainsley said.

‘Not only men, else...’

‘You know what I mean, Innes. Lots of women think it is wrong to enjoy what is perfectly natural, and downright sinful to want to enjoy it any way other than what this woman calls traditional.’

‘So we are conspiring to keep our wives ignorant, is that what you’re saying? Because I’d like to point out to you that you’re my wife, and I’ve been doing my very best, to the point of exhaustion, to enlighten you. In fact, if you would care to set that letter aside, I’d be happy to oblige you right now with a—what was it—variation?’

‘Really?’ Ainsley bit her lip, trying not to respond to that wicked smile of his. ‘I thought you were exhausted?’

He pulled her stocking-clad foot onto his lap and began to caress her leg from ankle to knee. ‘I’m also dedicated to providing Madame Hera with the raw material she needs to write the fullest of replies.’

‘You have provided Madame Hera with enough material to fill a book.’

‘Well, why don’t you?’

She was somehow lying back on the sofa with both of her feet on his lap. Innes had found his way to the top of her stockings and the absurdly sensitive skin there. Stroking. How did he know that she liked that? ‘Why don’t I what?’ Ainsley asked, distracted.

‘Write a book.’

His fingers traced a smooth line from her knee to her thigh, stroking her through the linen of her pantaloons. Down, then up. Down. Then up. Then higher. Finding the opening in her undergarments. Her flesh. More stroking. ‘What kind of book?’

Sliding inside her. Stroking. ‘An instruction book.’ Sliding. ‘A guide to health and matrimonial well-being, or something along those lines,’ Innes said. ‘Didn’t you mention to me once that you thought it would be a good idea? Madame could offer copies to her private correspondents. I’m sure your Miss Blair would be more than happy to advertise something of that sort discreetly in her magazine.’

‘I’d quite forgotten that conversation. Do you really think such a book would sell?’

‘You’re the expert, what do you think?’

She seemed to have stopped thinking. He was still stroking her. And thrusting now, with his fingers. And she was already tensing around him. Was it faster, her response, because of the experience of these past few weeks? Or was she making up for years of deprivation? Perhaps she was a wanton? Could one be a wanton and not realise it? The stroking stopped. Innes slid onto the floor. She opened her eyes. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Making sure your instruction manual covers every eventuality,’ he said, disappearing under her skirts.

When he licked her she cried out in surprise. Then his mouth possessed her in the most devastating way, and she moaned. Heat twisted inside her, and she began to tense, already teetering on the edge, as he licked and thrust and stroked. She gathered handfuls of her skirts between her fingers, clutching at her gown in an effort to hold on, but it was impossible. Such delight, such unbearable delight as he teased from her, that she tumbled over into her climax, shuddering, and shuddering again as he licked her into another wave, and another, until she cried out for him to stop because she really thought that the next wave would send her into oblivion.

* * *

‘What is it in those account books that is causing you to sigh so much?’ Several hours later, Ainsley was pouring their after-dinner coffee. The maid who helped out in the house had left, along with Mhairi, once dinner had been served, for the housekeeper preferred to sleep where she had always slept, in her quarters at the castle.

Innes stretched his feet out towards the fire and shook his head wearily. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘It obviously does, else you would not have been sighing.’

‘When it comes to sighing, I seem to recall there was someone else in this room doing their fair share earlier this evening. You didn’t say whether you approved of that particular variation, now I come to think of it.’

‘I thought it was obvious.’

‘A man likes to know he’s appreciated.’

‘You are.’

‘I’m looking forward to reading that particular chapter of your guidebook. I reckon it will tax even Madame Hera’s newfound vocabulary to describe it.’

‘So you were serious when you suggested that I write it?’ Her smile was perfunctory.

Innes frowned. ‘Why not? It makes perfect sense.’

‘And it will give me something to do.’

Innes put his coffee cup down. ‘Have you something on your mind?’

‘It’s been more than three weeks since the Rescinding. I don’t have anything to do, yet every time I ask you how things are going with the lands, you find something else to distract me. I’m wondering if tonight’s variation, as you call it, was simply a better tactic than telling me it was late, and that you were tired.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Nothing.’ She set down her cup. ‘They are your lands,’ she said, getting to her feet. ‘You are the one who has set himself the task of making Strone Bridge better than it ever has been. You did not consult me before you made that decision. Why should I possibly imagine that you would think my opinion worthwhile now, when you obviously have no idea how to go about it?’

‘Where on earth did that come from?’

‘From being ignored! I have tried. I have tried several times now to remind you of the terms on which I agreed to come here, and you’ve ignored me.’

‘But you have helped. The Home Farm. The Rescinding...’

‘And I’ve entertained you, too, when you’ve found the real problems of this place overwhelming.’

‘You’re joking.’

He looked at her aghast, but she was too angry to care, and had bottled up her feelings for too long to hold them in. ‘I don’t know why I’m still here,’ Ainsley said. ‘I’m not serving any purpose, and I’m a long way from earning back that money you lent me.’

‘Gave you.’

‘It was supposed to be a fee. A professional fee. Unless you’re thinking that it was the other sort of profession after all.’

‘Ainsley, that’s enough.’ Innes caught her arm as she tried to brush past him. ‘What has got into you? You can’t honestly believe that I deliberately—what was it you said?—distract you by making love to you?’

Ainsley stared at him stonily.

‘What?’

She shook her head. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘Which means that it does,’ Innes said wryly. ‘You should put that in your book, you know, if you’re including a section for husbands. Whenever your wife says it doesn’t matter, you can be sure it’s of dire importance.’

‘I could write the same advice for wives.’

‘I suppose I asked for that.’ Innes held out his hand. ‘Don’t go, Ainsley.’

She hesitated, but she did not really want to run away, so she allowed him to pull her down on to the arm of his chair. ‘I don’t think it’s deliberate,’ she said, ‘but when you don’t want to talk about something, you—you distract yourself. With me, I mean.’ She made a wry face. ‘I am not complaining. I did not even notice it until tonight.’

‘And you immediately decided that I was pulling the wool over your eyes. You should know me better.’

She flinched at the roughness in his voice. ‘I do. That was not deliberate, either.’

Innes rested his head against the back of the chair, closing his eyes with a heavy sigh. ‘You do know me, better than I know myself, it seems.’

He looked unutterably weary. Ainsley slid off the chair to stand behind him, put her hand on his temples. ‘Do you have a headache?’

‘I do, but I’m not going to risk another excuse,’ he said with a shadow of a smile.

‘Why won’t you talk to me, Innes?’

‘Because despite my resolve to be the saviour of Strone Bridge, I can’t see how it’s to be done. There’s nothing to discuss, Ainsley, and I’m gutted. That’s why I’ve not wanted to talk to you.’

She pushed him gently forward and began to knead the knots in his shoulders. ‘If the situation truly is irredeemable, you should turn your mind to something else more constructive, such as that pier of yours.’

‘Now that Robert has started work on the foundations and we have most of the supplies in hand, that pier of mine needs little of my time.’ Innes sighed. ‘That’s nice.’

Ainsley said nothing but continued to ease the tension in his shoulders, her fingers working deep into his muscles.

‘It’s different,’ Innes said after a little while. ‘The pier, the new road. I know what I’m doing with those. When things go wrong—as they no doubt will—I know how to put them right. You can’t just pluck new tenant farmers out of thin air. You can’t put heart back into the soil overnight. You can’t make a soil fit only for oats and barley yield wheat or hops, and even if you could, you can’t do anything about the rain or the cold. There’s so much wrong, and every solution I think of causes another problem somewhere else. There isn’t a solution, Ainsley. If the lands here were ever profitable, then it was a long time ago, and I will not clear the land just to turn a profit. I go round in circles with it all.’

‘If it’s any consolation, I do know how that feels,’ Ainsley said drily. ‘I also know from experience that bemoaning one’s ignorance and endlessly reassuring oneself that it is both impossible and futile to act is not only fruitless but a self-fulfilling prophecy.’

‘You are talking of your marriage.’

She gave his shoulders a final rub, then came round by the side of his chair to stand by the fire. ‘Yes, I am. I was afraid to speak up because I thought it would make things worse. I was afraid to act because I thought it would make the situation irretrievable. So I said nothing and I did nothing and—and if John had not died, who knows what would have happened, but one thing is for certain, matters would not have miraculously cured themselves.’

‘You’re telling me that I’m dithering, and I’m making things worse.’

‘I’d have put it a little more tactfully, but yes.’

‘You’re right,’ he said with a sigh, ‘I know you are.’

She settled in the chair opposite him. He was staring into the fire, avoiding her gaze. ‘It is the not knowing,’ he admitted. ‘The ignorance. That’s the hardest bit. I’m so accustomed to knowing every aspect of my own business, to being the man people turn to when there’s a problem. As I said, if something went wrong with the pier, or the new road, I’d know what to do. Or I’d be certain of finding a solution. But here, when it comes to the essence of Strone Bridge, I’m—I’m ashamed. People ask me questions. They look to me for solutions. And I don’t have answers. It’s—it’s— Dammit, Ainsley, I feel like a wee laddie sometimes and I hate it.’

‘Did you imagine I would think less of you for admitting to all this?’

Innes rubbed his eyes. ‘I think less of myself, truth be told. I don’t know what to do, and I don’t see how you can possibly help, for you don’t know any more of the matter than I do. What’s more, though the Rescinding bought me a deal of goodwill, in some ways it’s made matters worse, for not only have I raised all sorts of expectations, I’ve had to write off a load of debt, and the poor, honest souls who have been paying their rent without fail are now resentful of the fact that defaulters have been let off the hook.’

‘Oh. I hadn’t thought of that.’

‘Nor I. How could we have?’

Ainsley wrinkled her brow. ‘I don’t suppose you could simply balance the books somehow by writing the other rents off in advance. But no, that wouldn’t really balance the books, would it? It would simply mean that you were in more debt.’

‘It’s not the money that’s the problem, but...’ Innes sat forward. ‘You mean I could give the tenants who are up to date a rent holiday to even matters up?’

‘Do you think it would work?’

‘It’s worth a try. Have you any other genius ideas in that clever wee head of yours?’

Ainsley tried not to feel too pleased. ‘It was hardly genius. In fact it was pretty obvious.’

‘So obvious it didn’t occur to me. Does that mean that you’re a genius or that I’m an idiot? And be careful how you answer that, mind,’ Innes said, grinning.

‘Thank you,’ Ainsley said with a prim smile. ‘I will opt for genius.’

* * *

Waking with a start to the distinctive sound of the heavy front door closing, Ainsley found herself alone. Innes’s pillow was cold. She lay for a while going over their conversation this evening. She wished she hadn’t lost her temper, but on the other hand, if she had not, she doubted she’d have found the courage to say some of those things to him. She had hurt him, but she had forced him to listen. Then when he had, she had been lucid. She had been articulate. She had not backed down.

She sat up to shake out her pillow, which seemed to be most uncomfortable tonight. And her nightgown, too, seemed to be determined to wrap itself around her legs. She had put it on because it had been laid out at the bottom of the bed, as it was every night. Almost every morning, it ended up on the floor. Some nights, she never even got so far as to wear it.

She pummelled at her pillow again, turning it over to find a cool spot. Where was Innes? Was he angry with her? He hadn’t seemed angry. He’d seemed defeated. He was a proud man. Self-made. Independent. All the things she admired about him were also the things that made him the kind of man who found failure impossible to take, and talking about failure even worse. And she had forced him into doing just that. Was he regretting it?

She padded over to the bedroom window, but it looked inland, and there was no sign of Innes, who had most likely headed down to the bay and the workings that would become the pier. Hoping he had more sense than to take a boat out, telling herself he was a grown man who could look after himself and was entitled to his privacy, Ainsley crawled back into bed and screwed her eyes tight.

But it was no good. In overcoming her own reticence, she couldn’t help thinking she had forced him to confront a very harsh reality without having any real solutions to offer. Maybe there simply weren’t any. She sat up, staring wide-eyed into the gloom of the bedchamber, thinking hard. They were neither of them very good at discussions. She was too busy looking for signs that she was being excluded to listen properly, and Innes was too determined not to discuss at all.

Pushing back the covers, Ainsley knelt upon the window seat, peering forlornly and pointlessly out at the empty landscape. Innes was so determined to solve every problem himself, and it wasn’t just because that was what he was used to. He’d admitted it himself, this very night, how small this place made him feel. ‘Like a wee laddie,’ he’d said. He was ashamed, that was what lay at the root of his inability to ask for help, yet he had not a thing to be ashamed of. There had to be a way to save this place without causing further hardship. There had to be.

Ainsley grabbed what she thought were a pair of stockings. Only as she pulled them on, she saw that they were in fact a pair of the thick woollen ones, which Innes had started to wear with his trews. Though he dressed more formally for dinner, he almost always wore trews and a jumper for his forays out on to the estate these days. Tying her boots around the stockings, she decided that one of those heavy jumpers would provide her with much better insulation against the night air than her own cloak, and pulled it over her head. It smelled of fresh air, and somehow distinctively of Innes. The sleeves were far too long, but they’d keep her hands warm, and the garment came almost to her knees. Smiling fleetingly as she pictured Felicity’s face should she ever see her in such an outfit, Ainsley quit the bedchamber and made her way outside.

* * *

She found Innes sitting down in the bay, watching the ebbing tide swirl and eddy around the huge timbers that were the beginnings of the new pier. ‘I couldn’t sleep,’ Ainsley said, sitting down beside him on one of the thick planks that lay ready for use, and which had been brought on to the peninsula on an enormous barge that had caused a storm of interest in the village.

He put his arm around her and pulled her close. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘No, I am.’ Tempting as it was to simply leave it at that and give herself over to the simple comfort of his arm on her shoulders, her cheek on his chest, Ainsley sat up. ‘I do judge you, Innes. I am too much on the lookout for reasons to judge you to listen to what you’re telling me sometimes. I’m sorry.’

‘I forget,’ he said softly. ‘You seem so strong-willed, I forget that there was a time when you did not dare voice your opinions.’ He pushed her hair back from her face. ‘I know it’s not my business. I know you want only to forget, but—did he hurt you, Ainsley?’

‘No.’ She shook her head vehemently. ‘No. Not physically, if that’s what you mean.’

‘It’s what I mean.’

‘Then, no.’

‘Thank heavens. Not that I mean to belittle...’

‘It’s fine. At least it was not, but it will be.’ Ainsley gave a shaky laugh. The breeze caught the full skirts of her nightgown, lifting them up to expose her legs.

‘Are those my stockings you’re wearing?’

‘I thought they were mine, and then when I put them on they were so warm, I didn’t want to take them off.’

‘I’m glad you didn’t. I had no idea they could look so well. Nor my jumper, for that matter.’

‘I must look a sight.’

‘For sore eyes.’ He leaned over to kiss her softly. ‘I’m glad you’re here. I know we didn’t really quarrel, but it felt as though we were at odds, and I didn’t like it.’

The sky was grey-blue, covered by a thin layer of cloud. The distant stars played peekaboo through the gaps, glinting rather than twinkling. The sea shushed quietly, the waves growing smaller as the tide receded. Ainsley leaned closer to Innes, shoulder to shoulder, thigh to thigh, staring out at the water. ‘It wasn’t that he lifted a hand to me, not once, but I was afraid of him. Partly it was his fault, but partly it was my own. I told you that it was the debts,’ she said, ‘but it wasn’t just that. When you feel worthless, it’s difficult to have a say in other things, even when they concern you.’

‘Why would you feel worthless?’

She hadn’t planned this at all but it seemed right, somehow, to match Innes’s vulnerability by exposing her own. ‘The obvious reason,’ Ainsley whispered. ‘I could not give him what he married me for.’

‘You mean a child?’

She nodded, forgetting he could not see her. ‘Yes.’ She was glad of the dark. Such an old story, such an old pain, she had thought it long healed, but it seemed it was not. She could blame her tears on the wind, so she let them fall silently, biting her lip.

His arm hovered at her back. She could feel him, trying to decide whether to pull her closer or let her alone. She was relieved when he let it fall, let her wrap her own arms around herself, hug his jumper to her.

‘Ainsley, forgive me, but I know from how you were with me at first. I know that things between you and—and him— They could not have been conducive to your conceiving.’

He did not ever say John’s name, she noticed. He did not call him her husband. He was being absurdly delicate. If they had been discussing one of Madame Hera’s letters, he would have been much more forthright. If she had been one of Madame Hera’s correspondents, how much more of the truth would she have told? Ainsley shuddered. ‘When we were first married,’ she said, ‘things were—were normal between us.’ As normal as they were for many of the women who wrote to her, though she was not as fortunate as Mrs J-A, for John’s idea of traditional ministering took no account of her pleasure. For some reason, it was important that Innes know this. ‘Not as it is between us. He was not a—a gentleman in the sense you explained.’

‘No,’ Innes said gently.

So he had guessed that much, too. Ainsley tried to work out what it was she wanted to tell him. Not all. The memory of Donald McIntosh’s curse made it impossible to say it all, for though he had not actually cursed her, she felt as though he had. And though she knew it did not really diminish her, her flawed state, still she felt as though it did, and she couldn’t bear to reveal herself in that way to Innes.

Ainsley felt for his hand, seeking comfort and strength. ‘He was not a cruel man, not really, though some of the things he said and did felt cruel,’ she said. ‘It was when I first discovered the debts. That’s when he accused me of failing him. Until then, I had thought—told myself—hoped—that it was just a matter of time. Then, later, when our relationship deteriorated, he could not— He could not perform.’

It was not easy, but she had the words now; she understood so much more about herself now, and about men, since meeting Innes. ‘He blamed me. The worse things got between us— He said I unmanned him, you see. But I knew I had not because I saw him. Alone. I saw he could be aroused, only not by me.’

‘I remember now. You asked me about it, whether it was the wife’s fault.’

‘Yes. Don’t be angry. He’s dead. If he was not dead I wouldn’t be here.’

She felt his reluctant laugh. ‘Then I won’t be angry, for I’m very glad you’re here,’ Innes said.

‘Are you?’

She turned, trying to read his face in the darkness. It was impossible, but there was no need. He kissed her softly on the mouth. ‘I thought it was obvious,’ he said, borrowing her own words from earlier.

‘We’re neither of us very good at seeing that, are we?’

‘Not very.’ Innes touched her cheek, his fingers tracing a curve to her ear, her jaw, her throat. ‘It’s true, what you said earlier. There are times when I want to lose myself in you, to forget all the things I can’t resolve, but it’s you I want.’

‘Truly?’

‘You must not doubt it. You’re thinking that it’s another way of doing the same thing, my wanting you, his not. That the end result is you’re left out in the cold?’

‘Yes. I hadn’t— Not until tonight.’

Innes kissed her again. ‘Never, ever doubt that I want you for one reason, and one only. Whatever it is between us has been there from the start. I have never met a woman who brings me more pleasure than you.’

‘If you carry on kissing me, this thing, as you call it, will be between us again, and I’m trying to be serious.’ Ainsley sat up reluctantly, pushing her tangle of hair from her eyes. ‘I did not love John. I thought I did, but I did not. I thought he gave me no option but to ignore his—our—problems, but the truth is, I was relieved to be told they were none of my business, and when our marital relations broke down, I was relieved about that, too. What’s more, what I’ve learned from being with you, Innes, has made me realise it wasn’t just John who could not perform. I’m afraid my performance was pretty appalling, too. Partly it was because I didn’t know any better. Partly it was because I didn’t want to know. It was a mess I couldn’t fix because there was simply no solution.’

‘You can’t possibly be sorry that he died.’

‘That’s what Felicity said. I would never have wished him dead, but I don’t wish I was still married to him. You see what I mean?’

‘I’m not sure.’

Ainsley laughed drily. ‘I know, I’ve told this in a very convoluted way. I couldn’t give John a child, Innes.’

‘You don’t know that. It may not have been your fault. The chances are...’

Nil, was the answer. ‘Slim,’ Ainsley said, because she could not say it. ‘It’s not my fault, but it feels as if it is. Do you see now?’

‘You mean my lands.’

‘You could not help the fact that you were raised without any knowledge of them. You did not know what your father was doing—or not doing—in your absence.’

‘My elected absence. Regardless of who is to blame, they are in a mess.’

‘No, you blame yourself for the problem and for failing to fix it.’

‘I’m not accustomed to failing.’

Ainsley laughed. ‘Then we must make sure that you do not, but I don’t think the solution lies with making your lands more fertile. What we need to do is think differently.’

‘We?’

‘Yes, we,’ she said confidently. ‘Between your stubbornness and my as-yet-untested objectivity, we shall come up with something. We have to. But right now it’s very late, and it’s getting very cold. We’ll catch a chill if we sit here much longer, and you need to try to get a wee bit of sleep at least.’

Ainsley got resolutely to her feet, but Innes stood in front of her, blocking her path. ‘I’m not stubborn.’

‘You could have taken one look at the mess of this place and turned around back to your own life, but you have not. You’ve invested a lot more than money in the future of this place. What would you call that, if not stubborn?’

‘Determined? Pig ignorant?’ He pulled her into his arms, laughing. ‘Have it your way. How do you fancy taking a stubborn man to your bed? Because fetching as you look in that rig-out, what I really want is to take it off you, to lie naked in bed with you.’ He kissed her. ‘Beside me.’ He kissed her again. ‘Under me.’ And again. ‘Or on top of me.’ And again, this time more deeply, his hands on her bottom through the thin layer of her nightgown, pulling her up against the unmistakable ridge of his erection. ‘You see, this is me consulting you. Over, under, beside—the choice,’ he said, ‘is yours.’