Читать книгу René Lévesque - Marguerite Paulin - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

The Real Quiet Revolution

Monday morning at eight o’clock, Lévesque was at his Quebec City office before the others. The project he was most afraid of was the thorny language law that had to be passed as quickly as possible. He feared that the anglophone community and its representatives who moved in the same circles of high finance would band together against his government. A language law! Of all the Péquistes, Lévesque was one of the most reticent to regulate such a touchy issue. Even though he wished Quebec to be as French as Ontario was English, he wanted anglophones to keep their institutions and their rights. Voting on a language law was putting a bandage on a wound rotting away inside. “I want Quebec sovereignty so as to put an end to these quarrels senselessly dividing us.”

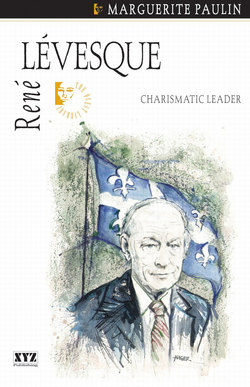

Archives nationales du Québec à Montréal/E6, S7, SS1, P771944, #16

René lévesque opens the Heritage Fair in Longueuil in 1977.

On the night of February 6, Corinne, on the verge of tears, cried out: “René has just killed a man!”

The accident occurred on Cedar Avenue. Suddenly, in front of him, he saw headlights and a stopped car. A young man was gesturing, signalling for him to avoid something. “What is this nutcase doing here?” Lévesque asked, accelerating. So as not to hit him, he swerved awkwardly to the left. The wheels of the car ran over a body. There was a man lying on the ground – a body on the slippery pavement. Lévesque was convinced that he’d killed him.

The victim, Edgar Trottier, was in his sixties and had no fixed address. On top of everything else – a homeless man! Even though they recognized the premier, police officers showed no favouritism and asked the usual questions. Had Lévesque been drinking too much? Had he made an error in judgment? Had he been absent-minded? Had he been wearing his glasses?

After the euphoria of the November victory, he plummeted to the depths of despair. For a moment, Lévesque thought he was finished. “Should I resign?” This affair contained all the elements of a big scandal. Already, rumour mongers were stressing the fact that the premier had not been alone in the car, but “had been accompanied by his personal secretary.” Such innuendo was false. While the English-language press deprecated the premier, the francophone media took pity on him. It wasn’t his fault. What was a pedestrian doing on the pavement, anyway? And what about the boy blocking the road, had he done something wrong? In surveys, the majority of respondents accepted the police report. Lévesque had not had too much to drink.

“You’re lucky this accident happened at the beginning of your mandate; you’re still at the honeymoon stage with journalists,” a counsellor remarked to him.

Lévesque could have done without this kind of sympathy. He just wished he’d never lived through such a tragedy.

That Wednesday morning the atmosphere in the bunker was strained. The cabinet was discussing a project that Doctor Laurin had dreamed up in secret with specialists on the issue. The cover of this thick file irritated René Lévesque: the hand placing an acute accent on the word “Québec” reminded him of someone slapping the fingers of an insubordinate. From the moment the text was presented, the ministers were at loggerheads: representatives from the Montreal ridings accepted Laurin’s work without a second thought. The others were dead against it. Lévesque was caught in the middle of the attacks and insults. Going over the proposed language bill with a fine-toothed comb, he was noncommital. Did his reserved attitude stem partly from his childhood in New Carlisle where he learned to speak English fluently? Meeting supporters of French unilingualism, Lévesque felt no urgency to act, which explained his aggravation as he shouted:

“For heaven’s sake, stop frightening everyone by exaggerating so much!”

But at the same time, he added that the Parti Québécois had the right to francize the city because Montreal should no longer have “this bastard face it used to when you couldn’t even ask for a pair of socks in French from a saleswoman at Eaton’s!” The session rose; they would have to find a middle ground.

The day before presenting the proposed Bill 101 to the National Assembly, René Lévesque summoned Camille Laurin to his office. The problem of signage was bothering him: having language police measure the size of letters to the nearest centimetre in store windows was out of the question. “Our law mustn’t prevent little pizzerias with three or four employees from surviving!” Doctor Laurin reassured him; Lévesque returned to the attack. He wanted to suppress Section 73, which said that at the request of either parent, “a child whose father or mother received his or her elementary instruction in English, in Quebec” could receive their instruction in English. He preferred reciprocity, giving anglophones from other provinces the opportunity to study in their language, providing that francophone minorities could enjoy the corresponding rights.

“We are still in Canada; you must not make your proposed legislation more difficult to swallow than sovereignty-association.”

The premier rose then sat down, agitated, smoking one cigarette after another.

“Listen up – if a problem arises, you, Camille Laurin, are the one who will suffer the consequences,” stated René Lévesque, who urged his minister to go himself and sell his Bill 101 to the people, clearly letting them know that he alone was responsible for this notion.

During its first mandate, aside from the Charter of the French Language and legislation on the financing of political parties, the Péquiste government undertook significant reforms. Suffice it to mention the anti-scab legislation, legislation on occupational health and safety, consumer protection, and agricultural zoning, the creation of the Régie de l’assurance automobile du Québec, and aid to small and medium-sized businesses through the employee stock savings plan. As premier, René Lévesque presided over this energetic social and economic catch-up, but sometimes confessed to his ministers that he would rather trade places with them than be head of state. Fortunately, he was lucky enough to lead diplomatic missions outside Quebec, a role that reminded him of his profession as correspondent. After New York came Paris. The tour of the great capitals continued. But this time, improvising was out of the question. Above all, the premier must not make a gaffe: France had a long aristocratic tradition.

“You will go to Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, of course.”

Lévesque remained indifferent. Was it necessary to make this pilgrimage to the tomb of General Charles de Gaulle?

“We’ll see – if I have time!”

This reply disconcerted his entourage, but they remained calm. They felt this was “no mere whim,” to use the expression employed by Lévesque for ending a pointless discussion. Colombey was a symbolic place; it would be a mistake to head straight to the capital and bypass Lorraine. Hadn’t General de Gaulle been the first foreign politician to bring the sovereigntist option to the front pages of international news?

The date was July 24, 1967. The president of the French Republic, during Expo in Montreal, had gone to City Hall. Then, to the amazement of the authorities, he had walked to the balcony where he made an impromptu speech. Carried along by the enthusiasm of the crowd, above a sea of fleurs-de-lis, his final words, distinct and direct, were “Vive le Québec libre!” These four words provoked one of the most commented-upon diplomatic incidents in history. “I was extremely upset,” remembered Lévesque who, near the balcony and crouching in front of a television set, had watched the speech broadcast live. Seeking to analyse the impact of this event, he’d been rivetted to the TV screen.

“I said: ‘Geez, De Gaulle, is going overboard!’ Comparing the euphoria of the Montreal crowd to the Liberation of Paris in 1944 was rather extreme. He was moving fast: in the summer of 1967, the Sovereignty-Association Movement hadn’t even been born yet! What I didn’t like was that the General, with all due respect, presented himself as a liberator with the idea of decolonizing us. We alone are the ones who will achieve independence, when we want, when the time is right.”

Then, after a few seconds went by, he added, grudgingly: “Okay, it’s fine. We’ll make a stop and visit Colombey. I’ll go meditate at the general’s tomb. After all, I do owe him this modest homage.”

Not in ten years had relations between Ottawa and Paris been so strained.

The Canadian Ambassador to France criticized President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s government for sympathizing with the sovereigntists. He feared above all that René Lévesque would take advantage of this to create special ties with the Élysée palace.

After a few days’ vacation in Provence, the Quebec delegation went to Lorraine, where it awaited dignitaries for the ceremony honouring Charles de Gaulle. Television, which followed his every move, scanned the PQ leader from head to toe. The moment the limousine door opened, the camera focused on the guest of honour’s feet: René Lévesque was wearing Wallabees!

“Your Monsieur Lévesque is so nice,” people said just about everywhere.

His nonchalance had a certain something that captivated those who approached him. He was relaxed – or “cool,” to use the in word of the mid-seventies: he came by it naturally. This first trip to France led to the signing of many economic agreements and sealed the friendship between France and Quebec, which had been growing since the late sixties. On this visit, René Lévesque was named Grand Officer of the Légion d’honneur. The ceremony was impressive: beneath the chandeliers of the gilded salon, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, President of the Republic, placed the rosette on the lapel of René Lévesque’s jacket. Lévesque, uncomfortable with all the pomp and circumstance, thanked him.

“He always wears the same suit,” quipped one reporter. “Is it the only one he owns?”

Forced to remain in the background during this trip, not enjoying the privileges of a premier’s wife, Corinne was determined that her partner finally decide to divorce so he could marry her.

But Lévesque didn’t listen to his companion’s complaints; he had other priorities. Time was passing and the deadline for the referendum approaching. In his office, he took stock of his government:

“The real Quiet Revolution is what we’re making happen now. And we’re the ones who are truly modernizing Quebec. In just one session, we’ve passed more than twenty-four laws, and not inconsequential ones. I am proud to have helped put an end to the Maurice Duplessis-style messing around in hidden funds. Our law on political party financing is unique, ahead of the times,” Lévesque pointed out, a cigarette between his fingers and martini in hand.

Lévesque emphasized the determination of the Department of Consumer Affairs, Cooperatives, and Financial Institutions, which had managed to pass a law on car insurance. No-fault insurance, which guaranteed insurance to all drivers, regardless of whose fault the accident was, was far from receiving unanimous consent in Cabinet. “We made life hard for her,” admitted the premier, referring to the minister responsible, Madame Payette. Her courage reminded him of the struggle he himself had led in the sixties to nationalize electricity.

But Lise Payette and René Lévesque had never really hit it off. “He’s a male chauvinist,” she said. “He looks at women, undressing them from head to toe – and he’s no feminist!” And Lévesque replied: “She holds it against me because I say she’s moody, but it appears that I am as well.”

Like in a classroom where the teacher has favourites, Marc-André Bédard, Minister of Justice, was one of those Lévesque liked most. But the PQ leader’s circle of close friends wasn’t very large. In any case, those not benefitting from his consideration were better off going unnoticed. The man was caustic, pitiless to any minister not in control of his files. In the caucus, the offender would bear the brunt of Lévesque’s wrath. “Go back and do your homework!” he would lash out in front of his colleagues. Time was precious. He knew he could ask a lot of his troops, he who spared no effort in his own work schedule.

“What about the referendum?”

Halfway through his mandate, the question returned with renewed vigour. For two years now, the PQ had shown themselves capable of governing Quebec: the economy was on track and the media were their allies. The social climate was less agitated than under the Liberal government. For example, in 1972, the leaders of three central labour bodies had defied the back to work legislation passed by the Bourassa government. Sentenced to jail, they became heroes and martyrs of the workers’ cause. The PQ, learning from the Liberals’ mistakes, tried to attract unionized workers and recruited a great many in the public and quasi-public sectors. But this fragile harmony was by no means guaranteed. The PQ had to hold its sovereignty referendum without further ado: procrastination would serve no purpose. The honeymoon between the unions and the Péquistes would end one day; the grace period was fading fast and at a second’s notice would be over for good.

In the flying saucer that was the bunker, the cabinet meetings continued to be contentious. As was his habit, Claude Morin would say: “Okay, whose life shall we make difficult today?” In fact, he said aloud what certain people thought to themselves: the government was taking on too much: “we’re getting up the backs of many voters who believe we are playing at being socialists.”

The gap between the radicals and the conservatives was widening. Fortunately for the PQ, René Lévesque’s charisma was still effective. Even when he resolved in favour of one side or another, he managed to make it unanimous. But all the pointless bickering left him perplexed.

“Lévesque embodies our contradictions,” remarked Doctor Camille Laurin. “He always seems to be sitting on the fence, unresolved, lukewarm.”

That morning, the aroma of burnt toast in the bunker confirmed the PQ leader’s presence. With his blackened toast, cup of strong coffee, and omnipresent cigarette, the premier was already at work. He would always remain a journalist. He opened Le Monde: in Cambodia, Vietnamese troops had overturned Pol Pot. Keen on international politics, he was interested in what was happening beyond the border. The front page of the New York Times described trouble brewing in Iran: the shah was fleeing his country, where Ayatollah Khomeini was being greeted as a redeemer. Quebec’s problems didn’t hold much weight alongside the human misery festering in the world.

His work finished, he set aside the quarrels of the various factions and quickly began a game of poker! This leaning of his was a source of contention. Certain people insinuated cynically that for Lévesque there were two kinds of members of the Assembly: card players – and others.

“There is a full committee at eight o’clock,” Lévesque announced to Marc-Andre Bédard who understood that that evening they would be playing cards till late in the night.

At the end of the session, René Lévesque gave a press conference. Reporters took notes. Yes, he would go on vacation. Where? He didn’t know yet. Before they asked “with whom?” Lévesque rose. There were persistent rumours. Recently divorced, he would not be free for long. On April 12, 1979, the premier tied the knot with Corinne Côté. He was fifty-six, she thirty-five. There would be no more unpleasant incidents like on that winter evening when Madame Barre refused to speak to Monsieur Lévesque’s secretary. He married a second time, in order to legalize a union over ten years old. And to please the woman he said he loved fiercely. Fidelity was another story.

After a week in the south of France, it looked as if the return to Quebec would be difficult.

While the Parti Québécois managed to rev up its troops for the referendum deadline, chaos reigned in Ottawa. At the end of March, Pierre Trudeau called an election that he lost on May 22 to the Conservatives. In his office, at the cocktail hour, with his close advisors, René Lévesque gloated:

“Things will be easier with Joe Clark in power.”

Trudeau was a thorn in the side of the sovereigntists. The worst was that he had star charisma: he was the man the majority of Quebecers loved, and that others loved to hate. And now he was gone from headlines, no longer undermining the enthusiasm of the Péquistes.

“Certain ministers want us to hold the referendum immediately. They’re in a rush. But I’d rather wait a little longer, until the fall or next year.”

Lévesque lit another cigarette. A deck of cards on the table. At eight o’clock they played poker.

“Do you wager we’ll win this referendum?”

The question was in vain. With Trudeau out of power, the chances of victory had never been so good.

René Lévesque was not prone to effusiveness. He had only cried twice: when Pierre Laporte died, and then more recently, when his mother died.

Diane Dionne had worn the pants in the family. At retirement age, she still travelled. By ship, because she hated airplanes. Alert, independent, after taking language courses, she decided to leave: once for Italy, another time for the Soviet Union.

Lévesque called her “Madame Pelletier” partly to aggravate her, but also because he had never really forgiven his mother for her remarriage to Albert Pelletier, a nationalist lawyer, long since passed away.

The death of his mother and his whole childhood resurfaced, carefree, happy images.

In New Carlisle, on the Baie des Chaleurs, a little boy, wild and free, looking at the ocean, as blue as his eyes.