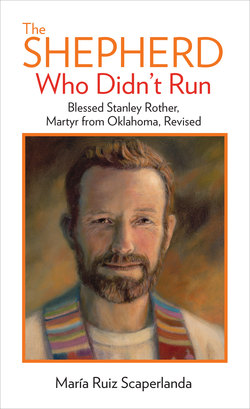

Читать книгу The Shepherd Who Didn't Run - Maria Ruiz Scaperlanda - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Love to the Extreme Limit

July 28, 1981: The Shepherd Who Didn’t Run

It was a quiet, clear night in the lakeside village of Santiago Atitlán. For almost a week now, the moderate, cool temperatures in the Guatemala highlands had been chilly enough for a jacket in the middle of summer.

Sounds travel far in this isolated region of Guatemala, where the only recurring nighttime noises are animal ones. No sound of A/C units. No sound of cars and highways. No planes flying overhead or trains nearby. The type of silence experienced by most people in the United States only when camping in the deep woods, during a storm blackout, or by someone living in farm country. It was a silence well familiar to Stanley Francis Rother, a native of Okarche, Oklahoma.

The sound of three men breaking into the rectory of St. James the Apostle Church at 1:30 a.m. must have carried well beyond the village square — their enraged voices and aggressive movements like nails hammering a public message of terror to any listening ear.

Wearing civilian clothes and ski masks, the three Spanish-speaking Ladinos (non-indigenous men), were familiar enough with the parish complex to know the precise location of the pastor’s upstairs bedroom. They rushed there first but found no one in the room.

Then across the hall they seized Francisco Bocel, the 19-year-old brother of the associate pastor, who had been working at the rectory and staying there provisionally. They put a gun to the terrified young man’s head and threatened to kill him if he did not take them to the pastor immediately.

Francisco led the attackers down the stairs and to the door of a corner utility room. He knocked, calling out in terror, “Padre, they’ve come for you.”

That’s when Father Stanley, aware of the danger to the young man, opened the door and let his killers in. Francisco was ordered to go back upstairs to his room and lock the door, and he did so — remaining there for the next 20 minutes.

The assailants wanted to kidnap Father Stanley, turn him into one of the desaparecidos (the missing). But he would have none of that. He was aware of Francisco, of the nine unsuspecting sisters in the convent across the patio, and of the other innocents in the rectory that night — all in danger of also being dragged away. And Father Stanley knew they would torture and, ultimately, kill him. He never called for help.

From his hiding place, Francisco heard the muffled noises of a struggle — bodies crashing into furniture and each other, several thuds. There was a gunshot. Then another. Then silence, followed by the sound of scrambling feet running away. After what seemed an endless period of silence, Francisco found the courage to come out of his hiding space. He rushed to wake up Bertha Sánchez, a nurse volunteer staying in the parish complex, and he ran to alert the Carmelite sisters in the convent across the courtyard from the rectory. “They killed him! They killed Padre Francisco!”

The women ran in and found Father Stanley shot in the head and lying in a pool of his blood. They immediately began to pray. His dear friend Bertha pronounced Stanley Francis Rother dead at the scene.

The Santiago Atitlán Mission: A Return to Ministry

How a 46-year-old priest from a small German farming community in Oklahoma came to live and die in this remote, ancient Guatemalan village is a story full of wonder and God’s providence.

When Pope St. John XXIII requested in the early 1960s that North Americans send missionaries to South and Central America, the Oklahoma Church responded.

In 1964, the then Diocese of Oklahoma City and Tulsa took over the care of the church of St. James the Apostle (Santiago Apóstol), the heart of the oldest parish in the Diocese of Sololá, dating back to the 16th century. But no resident priest had served the indigenous Tz’utujil community of Santiago Atitlán for almost a century. Oklahoma priests, sisters, and lay workers served the mission until 2000, when sufficient growth in local vocations allowed the Guatemala diocese, now called the Diocese of Sololá-Chimaltenango, to resume pastoral care.

From the onset, that first Oklahoma missionary team understood that the Tz’utujil are an agricultural people who retain much of their ancient Mayan culture and pride. This was a perfect fit for Father Stanley, a farming boy from the western Oklahoma town of Okarche.

When he arrived at Santiago Atitlán in 1968, Father Stanley instantly fell in love with the volatile and stunning land of volcanoes and earthquakes — but above all, with its people. His Tz’utujil Indian parishioners called him “Padre Apla’s,” which translates as “Francis” or “Francisco” in the native Tz’utujil language. When speaking in Spanish, they called Father Stanley “Padre Francisco,” based on “Francis,” his middle name, because it was easier to pronounce than the Spanish for Stanley, “Estanislao.” Over his years of service, Father Stanley helped develop a farmers’ co-op, a nutrition center, a school, a hospital clinic, and the first Catholic radio station in the area, which was used for catechesis.

And although he did not institute the project, he was a critical driving force in developing Tz’utujil as a written language, which led to translations of the liturgy of the Mass and the Lectionary, with the New Testament in Tz’utujil being published after his death.

In the most tangible way, Father Stan exemplified with his life and through his vocation what Pope Francis described regarding the distinctive ministry of men and women who choose a consecrated life: “A radical approach is required of all Christians, but religious persons are called upon to follow the Lord in a special way: They are men and women who can awaken the world.”

“Consecrated life is prophecy,” Pope Francis emphasized. “God asks us to fly the nest and to be sent to the frontiers of the world, avoiding the temptation to ‘domesticate’ them. This is the most concrete way of imitating the Lord.”1

“If It Is My Destiny That I Should Give My Life Here, Then So Be It …”

Once Guatemala’s civil war found its way to the peaceful villages surrounding beautiful Lake Atitlán, many people, like Father Stanley’s own catechists, began to disappear regularly.

Father Stanley’s response was to show his people the way of love and peace with his life. He walked the roads looking for the bodies of the dead, to bring them home for a proper burial, and he fed the widows and orphans of those killed or “disappeared.”

In a letter dated September 1980 to the bishops of Tulsa and Oklahoma City, Father Stanley described the political and anti-Church climate in Guatemala:

The reality is that we are in danger. But we don’t know when or what form the government will use to further repress the Church.… Given the situation, I am not ready to leave here just yet. There is a chance that the Govt. will back off. If I get a direct threat or am told to leave, then I will go. But if it is my destiny that I should give my life here, then so be it.… I don’t want to desert these people, and that is what will be said, even after all these years. There is still a lot of good that can be done under the circumstances.

In his final Christmas letter to Oklahoma Catholics published in two diocesan newspapers that same year, he once again concluded: “The shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger. Pray for us that we may be a sign of the love of Christ for our people, that our presence among them will fortify them to endure these sufferings in preparation for the coming of the Kingdom.”2

But a month later, and six months before his death, Father Stanley and his associate pastor left Guatemala under threat of death after witnessing the abduction of a parish catechist. However, he returned to his beloved Guatemala in time to celebrate Holy Week in April of 1981, ignoring the pleas of those who urged him to consider his own safety.

On July 12, 1981, in a statement read in all the nation’s parishes, the Guatemalan bishops denounced “a carefully studied plan” by the government “to intimidate the Church and silence its prophetic voice.”

“Just before he returned to Guatemala for the last time, he told me how much he desired to come back,” recalled Archbishop Emeritus Eusebius J. Beltran, in a 30th-anniversary message to the community of Cerro de Oro, one of the mission’s satellite churches near Santiago Atitlán.

“He knew the dangers that existed here at that time and was greatly concerned about the safety and security of the people. Despite these threats and danger, he returned and resumed his great priestly ministry to you.… It is very clear that Padre Apla’s died for you and for the faith,” said Archbishop Beltran, who served as bishop of Tulsa in 1981 when Father Rother was killed.

As We Get Started

During his seminary years in San Antonio, Stanley struggled in his studies, even failing his first year of theology. When the seminary suggested that he should consider a different vocation, Stanley requested another chance, and the supportive bishop agreed. He successfully completed his studies at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Father Stanley served the first five years of his priestly ministry without much notice in various Oklahoma assignments. But everything changed when he answered the call to serve at the mission in Guatemala, a decision that led him to find his heart’s vocation as a priest to the Tz’utujil people.

This farmer from Okarche, Oklahoma, who loved the land and recognized God in all of creation, was never afraid to dig in and get his own hands dirty — a trait deeply loved by his Tz’utujil people.

Certainly the fact that Father Stanley’s route to the priesthood was a difficult one only emphasizes the reality that his desire to serve the People of God as their priest never wavered. Over and over, both in his native Oklahoma and his adopted Guatemala, the stories involving Father Stanley highlight his unassuming, hard-working ethic, a perseverance he was known to execute all the way to stubborn!

Almost 35 years after his martyrdom, Father Rother is more than remembered by the parish community in Santiago Atitlán. The faithful devotion of the people make it clear that Padre Francisco is still witnessing the presence and power of God to his people.

From one generation to the next, the men and women of Santiago Atitlán continue to tell the story about the gringo from Oklahoma who became one of them: the priest who loved them, worked with them, stood up for them, and was even willing to die with them.

In a very real way, Father Stanley remains their priest.

As the stories of those who knew him will verify here, Father Stanley’s single-minded devotion was to living and embodying the Love of God he himself experienced — a Love that he believed with his whole heart was his mission to proclaim, in word and action, to all of humanity.

In my biography Edith Stein: St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, I quoted Edith Stein as declaring, “Pure spirits are like rays of light through which the eternal light communes with creation.… To believe in saints means only to sense in them God’s presence.”3

Father Stanley was a pure spirit, one of 13 priests — and the first American priest — slain during Guatemala’s 36-year guerrilla war, a tragedy that ultimately claimed an estimated total of 140,000 lives. This text is not meant to be a comprehensive collection or a definitive presentation on his life, or his death, or his cause for canonization. This book is meant to honor the faith and faithfulness of Stanley Francis Rother — Padre Apla’s — a brilliant ray of light in the midst of a very dark period in the history of Guatemala and the Americas.

“Who are martyrs? They are Christians who have been ‘earned’ by Christ, disciples who have learnt well the sense of that ‘love to the extreme limit’ which led Jesus to the Cross,” Pope Francis remarked in October 2013, on the beatification of 522 Spanish martyrs who were killed during the anti-Christian persecutions of the 1930s.

“There is no such thing as love in installments, no such thing as portions of love. Total love: and when we love, we love till the end.

“On the Cross, Jesus felt the weight of death, the weight of sin, but he gave himself over to the Father entirely, and he forgave. He barely spoke, but he gave the gift of life,” Pope Francis continued. “Christ ‘beats’ us in love; the martyrs imitated him in love until the very end.…We implore the intercession of the martyrs, that we may be concrete Christians, Christians in deeds and not just in words, that we may not be mediocre Christians, Christians painted in a superficial coating of Christianity without substance — they weren’t painted, they were Christians until the end. We ask them for help in keeping our faith firm, that even throughout our difficulties we may nourish hope and foster brotherhood and solidarity.”4

There was nothing “painted” in Stanley, the young man who chose to follow Jesus as his disciple:

• Stanley, the seminarian who endured difficulties, even failure, yet persevered in his calling to the priesthood;

• Father Stanley, the young parish priest who put aside his fears, courageously agreeing to serve the People of God in Oklahoma’s mission in Guatemala;

• Father Stanley, the man who struggled to pass Latin and learn Spanish, yet succeeded in learning the rare and challenging Mayan dialect of his Tz’utujil parishioners;

• Father Stanley, the Okarche farmer who believed plowing the fields manually next to the Tz’utujil farmers was part of his vocation as a minister of God’s love;

• And finally, Father Stanley, the shepherd who chose to face death rather than abandon his flock — the shepherd who didn’t run.

It is my hope and my prayer that in the telling of Father Stanley’s story I succeed in introducing you to one person who loved “to the extreme limit,” as Pope Francis described, in making God’s presence real, tangible to the people in his life — by living, loving, and being himself completely.

To paraphrase the question asked in the Gospels by incredulous people about Jesus of Nazareth: can anything good come from Okarche, Oklahoma? I invite you to come and see.

May the farmer from Okarche inspire you as he has me!

––

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.…

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

— T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets, Quartet No. 4: “Little Gidding,” Section V