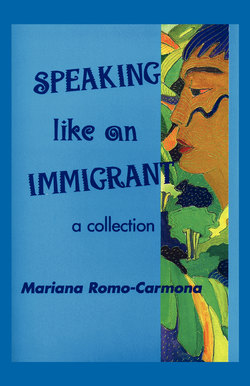

Читать книгу Speaking Like An Immigrant - Mariana Romo-Carmona - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеSpeaking Like An Immigrant takes us through a journey that flows through geographic and cultural spaces that are ever present within each other, the Chile of the past and the new lands of the present. The Chile of the author is in New York as well as in the lands of witches or memories of adolescence she conjures, and they become part of one another. The speaking done in this book does not conform to the voice of the immigrant imagined in the conventional vision of the American Dream.

Mariana Romo-Carmona’s voice evokes dreams that defy, unmask, and force us to rethink customary knowledge. The unmasking of conventions presented in this collection does not limit itself to revealing the racism, sexism and heterosexism of the most reactionary visions of that American Dream. Through these narratives, the author also questions assumptions of unitary, monolithic subjects and conventional forms of activism coming from feminist and lesbian paradigms.

Speaking like an Immigrant exposes the fallacies of the American Dream portrayed in the mass media as access to the latest sportswear advertised by the super stars, comfortable homes, and hi-tech entertainment, the symbols of status, happiness and well being promised to those that follow the work ethic. In the title story, the narrator is admonished to “work hard,” to avoid ending shining shoes on the Staten Island ferry. The surreal narrator of “The Web” (1994), explains her alienation as a loss of connection: “We have all but stopped speaking the language of our mother… I can’t live alone without the web.” In “2280,” written in 1988, her futuristic vision of the northern continent, Romo-Carmona demystifies the glowing, polished land of opportunity; her vision of the future does not mirror the promise of progress that space age technology offers. In her narratives, Romo-Carmona presents a reality experienced by more and more Americans in the United States who, in spite of working hard and long hours, find that the gap between their earnings and those of the rich continue to widen.

To be successful, immigrants are told, you must become American, you must assimilate; this is the key to the “American Dream” presented by dominant cultural paradigms. This vision of becoming American means to leave behind, to rid oneself of the past and look forward to something better. This “dream” imposes a fragmentation of the self. Those parts of our personal and collective histories lived prior to coming to the United States are deemed worthless, inferior and many times even shameful. This makes us invisible and produces the feeling of never belonging, of being faceless, voiceless. Becoming an American is to become someone without a past, without a history. As Romo-Carmona says, “It doesn’t matter what country I come from, to you they’re all the same.” The term American as used in the United States evokes images of dominance and hegemony. It attempts to make insignificant the other peoples and parts of the globe that are also America. The “dream” that has been constructed of “America” has attempted to erase the history of the colonization of Native Americans and Mexicans who inhabited this territory prior to the existence of the United States of America; to blot out the fact that this country was built through an economy based on the enslavement of African people. It forgets the history of brutal exclusion of Chinese at the turn of the century when the slogan unfurled by political parties and labor unions was “the Chinese must go.” The lynch mobs that hung Chinese immigrants on lamp posts and burned entire Chinese communities on the West coast are also not remembered. The “dream” obviates the internment of US citizens of Japanese origin in concentration camps. It has attempted to conceal the history of colonization of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and the ongoing exploitation of “third world labor.”

The voice that we hear in Speaking like an Immigrant takes us back to Chile. It is a trip through the desert with Mamá, through narrow roads that lead to mountain villages where there are flowers and ice, rivers, ravines, and “rock walls so tall that streams of water broke from the stone.” We hear stories of ancient times and the people of the sun. We visit churches where miracles occur, uncover tombs and learn of lost travelers who wander for eternity in the sand. We learn about life and death and the wonders of the world through the eyes of a child. Chile, Mamá, el abuelo y la abuela. Gabriela y Susana, are vital forces that are necessary to capture the present and alleviate the pain of feeling alien.

Mariana Romo-Carmona’s stories lead us outside the constraints of a space where we are asked to deny parts of ourselves and fragment our lives. She situates herself in the interstices of geographic and cultural boundaries to seek refuge from the splits and fissures imposed by world views that define us as foreigners, excluded, invisible, not American and therefore, people who do not belong. This new place is one inhabited by a multiplicity of realities and identities that constitute experiences of wholeness. In this book Mariana Romo-Carmona captures experiences that are not only hers but that of many immigrants whose lives are both here and there, and present in their journeys.

The memories of Chile captured in these stories are more than those of a physical and cultural space that is yearned for. In “The Virgin in the Desert”, these memories are set against the backdrop of the corruption of local politicians and government officials and the discrimination against immigrants crossing the desert from Bolivia. The churches described still evoke the brutal history of Spanish colonization after almost five centuries. The more recent history of the jailing and tortures of the thousands who “disappeared” under the Pinochet regime is presented in “Dream of Something Lost”.

Memories of Chile are also presented through lesbian voices. The awakening of erotic love described in “Gabriela” is inextricably tied to the countryside of Chile. The physical and cultural space Romo-Carmona describes is etched into the exhilaration of the young bodies aroused by the first touch of another woman. As Romo-Carmona writes, she appropriates the being that has been made invisible and voiceless by heterosexism. At the same time, the author poses questions that lead us away from conventional definitions that come from within the lesbian community itself. What is a lesbian of color? What is that experience that lesbians of color are expected to articulate, the ones everyone wants to hear in a language we can all understand? What constitutes lesbian of color activism? Discovering, understanding and appropriating lesbian and immigrant as vital, diverse and intertwined experiences is a process that the reader comes to know throughout the pages of this book.

In Speaking like an Immigrant we discover realities of many dimensions, multifaceted characters, and a wide range of experiences that contrast with the homogenization that characterizes stereotypes of immigrants, of women and of lesbians. In Romo-Carmona’s narrative, we experience fear, poverty and abandonment, but we also live hope, love, passion and unity with nature. We bridge realities that seem distant and find connections between people who seem to have very little in common.

Speaking like an Immigrant is both timely and urgent in the political climate in which we live where the words foreigner and immigrant have increasingly become racialized. The speaking done in this book challenges the growing racist and xenophobic forces that wish to instill fear and hatred towards immigrants. While yesterday’s immigrants are constructed n as white and European, many more that come to the United States today are brown and from countries of the Third World. Previous immigrants are portrayed as having successfully assimilated, while today seen as foreigners and aliens. Although they are a smaller proportion of the total United States population than they were at the beginning of the twentieth century,in talk shows and senate hearings we are presented with the image of hordes who will take over the country. Folks who do not wish to openly point to the color of the more recent immigrants, argue that their concerns about immigration are economic. Those people, the argument goes, place an undue burden on public services.

It is convenient and easy to forget that immigrants satisfy a demand for labor and pay taxes. Those bold enough to unabashedly object to the color of today’s immigrant population argue that an ethnic revolution is taking place. They claim that the growth of the Latino and Asian populations in the United States will alter the racial make up of this country making whites no longer a majority. They remind us that the founding fathers envisioned a white society, not a multiethnic one, and they wish to keep it that way.

In the national political discourse, then, immigrants have become non persons; they have no rights although they contribute their labor to this society. Border patrol vehicles chase people crossing on foot until they are tired and can no longer run. “Tonk,” the repeated sound of heavy flashlights hitting the heads of would be crossers in the night, has become the derogatory slang for Latino immigrant. Private citizens on the United States side of the border stage protests against immigration by shining bright lights toward Mexico to expose those waiting to cross. They are answered with mirrors that reflect the lights back on the United States as if to bare the hypocrisy of anti-immigration policies. As the economic boundaries between the United States and Third World countries have been modified to facilitate the flows of capital and profits, the flow of people has also increased. While the first is hailed as a positive and civilizing mission that brings progress to the world, the people whose previous forms of subsistence have been eliminated are considered dispensable. The flow of capital must remain uninhibited, while the flow of people must be brutally restrained. The current wave of anti-immigrant hatred is directed toward people who fit the stereotype of immigrant whether they are citizens or not, whether they are immigrants or have lived in the United States for centuries.

The author’s use of English, Spanish, and her translations represents a writer’s voice always in transition; it reflects a consciousness hewn from both languages and captures the forces that give life to her writing. In this way as well, this book reaffirms a different dream. Many immigrants have lost the language of their parents because of pressures to assimilate or because they have succumbed to the association of Spanish with deficiency and remediation. Romo-Carmona defies stereotypical images and speaks like an immigrant, a person who has claimed her past and her present, her ability to be whole, an agent of change. For Mariana Romo-Carmona writing is a vehicle to break dominant paradigms. The re-ordering she has achieved transcends her own experiences and traces paths towards new understandings of inclusion.

Elizabeth Crespo– Kebler

Puerto Rico and Central Pennsylvania, 1998