Читать книгу La muchacha de los ojos tristes - Mariana Romo-Carmona - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеQuite often, the structure and meaning of a collection of poetry only becomes evident for the poet as she writes the very last line of the last poem in the book. But it also seems unthinkable that the idea had not always been there, keeping vigil as she writes and revises, so tightly connected does each piece seem at the end of the long, solitary process.

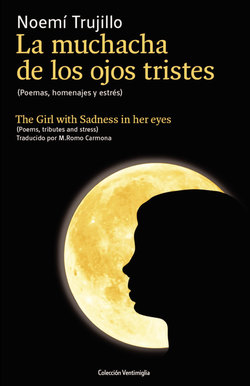

So it is with this particular collection by Noemí Trujillo Giacomelli, a young poet from Barcelona, for whom this book is the third and most awaited to date. La muchacha de los ojos tristes: The Girl with Sadness in her Eyes, seems to be a poetic staircase of images and themes provided by a long line of poets, leading to the author’s own words. Beginning with the epigraph from Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven,” which introduces the lovely prologue by the poet, Santiago Tena, every idea is a step for Noemí Trujillo’s poem to jump onto the next. The structure is sheer inspiration, one that helps to keep the words in motion and alive each time a reader opens the book.

With Emily Dickinson’s famous lines, “One need not be a Chamber— to be haunted” the mood is established for this poem where the speaker paints a portrait of herself in Dickinson’s image. This image, that of a girl “with sadness in her eyes” is invented, suggested by Dickinson’s own image of herself as a haunted chamber, and therefore free to continue to evolve in Noemí Trujillo’s poem. As the poems follow, each epigraph becomes a tribute to the poet as well as another step to create the first line of the poem that follows. With this brilliant structure, Noemí Trujillo evokes mood, tone, and imagery from the work of poets before her time, such as Storni, Plath, and Pizarnik, to accompany her creations which echo the poets of her own generation— Yolanda Sáenz de Tejada, Eva Márquez, Ismael Pérez, and younger writers, such as Silvia Oviedo, from whose lines about courage and guts, Trujillo steps off to the last poem.

Noemí Trujillo writes in free verse with a rhythm that seems natural, and flows following the pull of her emotions. In a poem aptly paying homage to Ann Sexton, “Un avión subterráneo” (An Underground Plane), the truncated lines hit a marked, violent cadence as the poet’s body is wounded from within. One reads confidently through these poems, open to images and motion precisely because the meter seems uncomplicated. Using Sharon Olds’ line, “Stop talking about conflict,” this poet does not enlist Olds’ famous line breaks to write “Intento ser mejor persona” (I Try to Be A Better Person), instead she hammers out the words, one truth at a time. There are few obvious rhyme patterns, enjambements or other devices to either define or restrain the lines. Rather, Trujillo uses the breakdown of words within a line to give power to her meanings:

I need to take a breather

change jobs,

write less,

buy a gun,

…

By the time the speaker reaches the painful plea of her erotic rendering, we have witnessed the diminution of desire in the lines, change jobs,/write less, but also accepted the rapid shift in intensity: buy a gun,/ so that when the poem ends there is no resistance from the reader. We are open.

Another instantce of that breaking down effect is in “Tengo la sangre rara” (I Carry a Strange Blood), where Trujillo utilizes a one-word line— “y/” (and/) to slow down the progression of the poem as if suggesting the threat of the dangerous blood clot inexorably approaching:

Now I am full of

radioactive residue

and,

nevertheless,

Again, in “Hay tardes” (Evenings), the breakdown of lines to just one word shows the poet’s ability to control both meter and impact, as in, “There are nights when silence/cuts/like a wire/while I write…” The single word makes the image of a wire that “cuts,” indelible.

It is the unexpected power in these seemingly gentle poems, the almost caressing language that is wielded so expertly, and the open position of the speaker beside her subject that makes them unique and valuable in contemporary literature. As translator in this project, my work is about transporting the artistry all-in-one piece, from one language to the other: Art cannot be faked. Readers in English of the work that this poet has dreamed up in Spanish, will be able to receive it whole, because of its solidity. Part of my work is to wander through the naked planks of language to discover what will emerge on the other side. It must be honest work; even though translation can never be exact, and therein, perhaps, lies the sadness along with the joy. Yet, look at how well Emily Dickinson’s words have accompanied us since the 19th century and through the crossing of the Atlantic from Amherst to Barcelona, and then back again, to New York City.

Noemí Trujillo chooses the voice of a woman in love, or, a poet who writes because she must, but while the reader encounters the universality of a soul in pain, the voice is not tame. The voice is not defeated. The voice knows her power and exacts her vengeance when she must. This voice, ultimately, reflects facets of women’s lives, of power gained and lost, of eroticism unbound and creativity released. At least, for today, for this book. For a poet, the success of her craft lasts only long enough for it to change and evolve, if she is willing. And I believe she will.

Mariana Romo-Carmona

New York City, February, 2011

Introducción A menudo la estructura y el significado de un poemario sólo se hace evidente a medida que la poeta escribe las últimas líneas del último poema del libro. Pero también parece incomprensible que la idea no haya estado siempre allí, velando mientras ella escribe y revisa, por la perfecta relación que existe entre cada pieza al llegar al fin de un proceso largo y solitario. Así es con esta colección en particular, de Noemí Trujillo Giacomelli, una joven poeta de Barcelona para quien este tercer libro parece ser el más ansiosamente esperado hasta ahora. La muchacha de los ojos tristes: The Girl with Sadness in her Eyes, da la impresión de ser una escalera poética de imágenes y temas prestados por una larga tradición de poetas, que nos llevan a las palabras de la poeta misma. Comenzando con el epígrafe de Led Zeppelin que introduce el hermoso prólogo del poeta, Santiago Tena, cada idea es un peldaño desde el cual los poemas de Noemí Trujillo saltan al siguiente. La estructura es pura inspiración, una que mantiene las palabras en movimiento y las hace renacer, cada vez que un lector abre el libro. Con las famosas palabras de Emily Dickinson, “No hay que ser una casa— para tener Fantasmas—” el ambiente se establece con este poema cuando la poeta se retrata en la imagen de Dickinson. Esta imagen, la de una “muchacha de los ojos tristes”, es inventada, sugerida por la propia imagen de Dickinson como una habitación encantada por fantasmas, y por lo tanto libre para evolucionar en el poema de Noemí Trujillo. A medida que continúan, los epígrafes se revelan no sólo como homenajes sino como pasos en la creación de los poemas siguientes. Con esta brillante estructura, Noemí Trujillo evoca el ambiente, tono e imágenes de los poetas anteriores a ella, como Storni, Plath, y Pizarnik, para acompañar sus creaciones con los ecos de los poetas de su propia generación— Yolanda Sáenz de Tejada, Eva Márquez, Ismael Pérez, y escritores más jóvenes, como Silvia Oviedo, desde cuyas palabras sobre “la valentía y agallas”, Trujillo salta a su último poema. Noemí Trujillo escribe en verso libre con un ritmo que parece natural, y fluye siguiendo la marea de sus emociones. En un poema muy apto como homenaje a Ann Sexton, “Un avión subterráneo”, las líneas truncadas anuncian una marcada y violenta cadencia, cuando el cuerpo del poeta sostiene una herida interna. Uno lee estos poemas con confianza, abierto a las imágenes y al movimiento precisamente porque su métrica parece carecer de complejidad. Utilizando el verso por Sharon Olds, “Stop talking about conflict” (Deja ya de hablar de conflictos), nuestra poeta no se arma de las divisiones bruscas que distinguen a Olds para escribir “Intento ser mejor persona”, sino que emite las verdades, cada una como un martillazo. Aquí se encuentran pocas rimas obvias, encabalgamientos u otros instrumentos para realzar o definir un verso. Al contrario, Trujillo emplea la disminución de las palabras, acortando así los versos, para prestarle impacto al sentido de su poema: Necesito darme un respiro cambiar de trabajo, escribir menos, comprar pistolas, … Cuando la narradora llega a la dolorosa plegaria de su retrato erótico, ya hemos sido testigos del desvanecer del deseo en los versos, cambiar de trabajo,/escribir menos, pero también hemos aceptado el rápido cambio de intensidad: comprar pistolas,/ de modo que al final ya no queda resistencia del lector. Estamos abiertos. Otra instancia del efecto de aquella reducción se encuentra en “Tengo la sangre rara”, donde Trujillo escribe un verso con una sola palabra— “y/” para desacelerar la progresión del poema, como para sugerir la amenaza de la peligrosa trombosis que se acerca inexorablemente: Ahora estoy llena de residuos radiactivos y, sin embargo, … De manera similar, en “Hay tardes”, la disminución de una frase a una sola palabra demuestra la habilidad de la poeta para controlar la métrica y su impacto, como aquí, “Hay noches en las que el silencio/corta/como un alambre/mientras yo escribo”. La palabra sola logra sacar una imagen de un alambre que corta, y es imborrable. Es el poder inesperado de estos poemas que parecen delicados, casi acariciando el lenguaje y manejándolo de manera experta, que, junto a la posición abierta de la que habla junto a su tema, hace que sean únicos y valiosos en la literatura contemporánea. Como traductora de este proyecto, mi trabajo consiste en transportar de una pieza lo artístico de un idioma al otro: el arte no se puede fingir. Los lectores que lean en inglés el trabajo que esta poeta se ha imaginado en español, podrán recibirlo entero gracias a su solidez. Para mí, un aspecto de la traducción es el deambular por las tablas desnudas del lenguaje para descubrir lo que surgirá en el otro lado. Necesita ser un trabajo honesto; aun cuando la traducción jamás pueda ser exacta, y allí, tal vez, radica la tristeza junto con la alegría. Sin embargo, vean lo bien que las palabras de Emily Dickinson nos han acompañado desde el siglo 19, y a través del atlántico, de Amherst a Barcelona, y de vuelta a Nueva York. Noemí Trujillo elige la voz de una mujer enamorada, o de una poeta que escribe porque le es necesario, pero mientras la lectora se encuentra con lo universal de un alma que sufre, la voz no ha sido domada. La voz no ha sido vencida. La voz reconoce su poder y se venga cuando debe vengarse. Esta voz trata, al fin, un reflejo de las muchas facetas de la vida de las mujeres, del poder que se obtiene y se pierde, del erotismo desencadenado y la creatividad liberada. Por lo menos hoy, en este libro. Para una poeta, el éxito de su arte dura sólo lo suficiente para que cambie y se transforme, para que evolucione, si ella está preparada. Y creo que lo está.

Mariana Romo-Carmona

New York City, February, 2011