Читать книгу Abundant Beauty - Marianne North - Страница 9

ОглавлениеMARIANNE NORTH:

AN INTRODUCTION

. . . . . . . .

by Laura Ponsonby

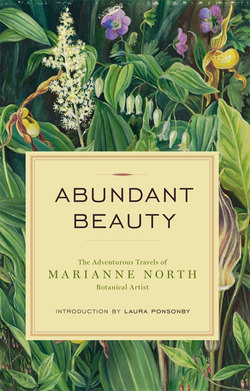

MARIANNE NORTH was a remarkable Victorian artist who travelled around the world to satisfy her passion for painting plants. At a time when women rarely travelled alone, many of North’s expeditions to remote areas of the globe were fraught with danger, but also with adventure and opportunity. The artistic results of these epic journeys can be seen in the Marianne North Gallery at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, which was designed by her friend James Fergusson and generously donated by the artist herself. Entering the gallery for the first time and seeing tier upon tier of brilliantly coloured oil paintings of plants, landscapes, birds, and animals is a breathtaking experience. The collection includes more than eight hundred paintings, completed in less than thirteen years of travel, and under them a dado made of 246 types of exotic woods collected by North. The gallery is believed to hold the only permanent solo exhibition by a woman painter in Britain and is certainly one of Kew’s greatest treasures.

MARIANNE NORTH WAS BORN IN Hastings, Sussex, in 1830, the elder daughter of Janet North and Frederick North, Liberal Member of Parliament for Hastings. She spent much of her youth travelling in England and Europe, and although she took a sketchbook, as was customary for young Victorian women travellers, music was her mania. It was only when her beautiful contralto voice deserted her that she took up painting in earnest, first in watercolour and later in oils.

Through her father’s connections, North knew many people who encouraged and supported her work. She received some tuition from the Dutch flower artist Magdalen von Fowinkel, and from Valentine Bartholomew, flower painter to Queen Victoria. In 1867, Robert Dowling, an Australian artist who lived in London, introduced North to oil paints. It was an event that changed her life, so that painting became, in her words, “a drug like dram-drinking, almost impossible to leave off once it gets possession of one.” Edward Lear, the nonsense writer and brilliant artist, was also a great friend and an admirer of her colourful paintings.

When North was twenty-four, her mother died and on her death bed made her daughter promise never to leave her father. True to her vow, North and her father continued travelling to Egypt, Syria, and various European countries. It was on excursions to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, that she became aware of glorious tropical flora. Sir William Hooker, the director, once gave North a beautiful hanging bunch of flowers of Amherstia nobilis, a tree from Burma, which made her long to visit the tropics.

Frederick North’s death in 1869 had a devastating effect on his elder daughter; the “one idol and friend of her life” had gone. However, this meant that North was at last free to visit the tropics. She once wrote that she was “a very wild bird” and liked liberty. At the age of forty she began her astonishing series of trips around the world. Between 1871 and 1885, she visited the United States, Canada, Jamaica, Brazil, Tenerife, Japan, Singapore, Sarawak (Borneo), Java, Sri Lanka, India, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the Seychelles, and Chile. Her aim was to paint plants in their habitats and to educate people on the sources of certain products.

North was a great networker. She always made certain to obtain plenty of letters of introduction before she set off on her travels. Fortunately, her father had known many distinguished scientists, botanists, artists, writers, and politicians who were able to put her in touch with people all over the world. She never cared for staying in government residences, preferring less grand accommodation—friends’ or acquaintances’ homes, boarding houses, inns, hotels, or primitive huts. In Sarawak she was a guest of Rajah and Rani Brooke in their official residence; the rani found “dear Miss North” exhausting but nevertheless enjoyed her visit. In Java, North had “a big letter” from the Governor General asking all officials, both native and Dutch, to feed and lodge her and pass her on to wherever she wanted to go.

In Sri Lanka she spent some time staying at the house of an English judge near the Peradeniya Royal Botanic Garden west of Kandy. Later she was photographed at Kalutara by famous Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. In India, where she stayed for well over a year, she was a guest of Dr. Arthur Burnell, a distinguished scholar and authority on South Indian languages, who became a great friend. The viceroy, Lord Lytton, and his wife entertained North in Simla and looked at her paintings. When Charles Darwin advised her to investigate the flora of Australia and New Zealand, she took it as a “Royal command” and went at once. North considered Darwin the greatest man living and had hoped that he would open her gallery in 1882, but sadly he died some weeks before the event.

North was a forthright and unusual woman who was not easily swayed by convention or other people’s views. Her brother-in-law, John Addington Symonds, described her as “blond, stout, tall, good humoured and a little satirical.” Although she came from a distinguished and wealthy family, her upbringing was not completely conventional, and people are apt to give her views she did not hold or to frequently misinterpret her actions. She was a non-believer and proudly declared herself a heathen; North particularly hated the “mumbo-jumbo” of church services and contrived to avoid them. She also did not care for the social round with its frivolous chatter. Despite her considerable charm and great sense of humour, she could be autocratic and, in her words, prone to “one of those rages which are sometimes necessary.” And while some of her remarks about native peoples would be unacceptable to modern readers, she easily befriended people of many races and backgrounds, as long as they were interesting and hard-working.

Revelling in adventure, North was excited by the dangers she often encountered, and she experienced an extraordinary variety of modes of transport. She was an accomplished and intrepid horsewoman, sometimes riding for eight hours a day; she was occasionally thrown to the ground, but it never seemed to worry her.

North was also a keen conservationist and frequently lamented the wanton destruction of forests and wildlife. Sir Joseph Hooker, the second director of Kew, stressed the importance of her paintings as historical records, particularly as many of the plants were “already disappearing or [were] doomed shortly to disappear before the axe and forest fires, the plough and the flock, or the ever advancing settler or colonist.” In recognition of her discovery of new plants, North has four species and one genus (Northia) named after her.

Although she did not consider herself a feminist and was not interested in women’s suffrage, North was a great supporter of women. She was particularly keen to promote the work of other women artists (although she was often irritated by certain young ladies who made stupid remarks about her paintings). In a letter to a friend, she lamented the role of the married woman: “…the wife was a sort of upper servant to be scolded if the pickles are not right.” In the last codicil to her will, she expressly desired that an annuity left to a woman friend be for the friend’s own use, free of her husband’s control.

North was a friend of Barbara Bodichon, the great feminist and fighter for women’s education. Bodichon was the illegitimate daughter of the radical Member of Parliament Benjamin Leigh-Smith, and while many friends and relations refused to acknowledge the “tabooed” family, she was warmly received by the Norths. Bodichon was also an excellent painter and a friend of the author George Eliot, who also admired North’s paintings.

IN 1884, AT THE END of her trip to the Seychelles, North’s health began to break down. She returned to England, but after a brief rest she decided to visit Chile. She was still suffering from what she called her “nerves,” but she was determined to paint the intriguing Monkey Puzzle trees she knew she would find there. After a stop in Jamaica, she returned from this, her final voyage, in 1885. She continued arranging the paintings in her gallery and finally retired to a house in Gloucestershire where she made a wonderful garden. She had always kept a detailed record of her travels, and so she also continued writing her autobiography, Recollections of a Happy Life, which her sister, Catherine, eventually edited and arranged for publication. North died on August 30, 1890, at the age of only fifty-nine.

Marianne North was a fearless traveller and accomplished painter, and undoubtedly a great inspiration to many others. She had extraordinary energy and determination, and considerable artistic talent, and she made a significant and noteworthy contribution to the study and appreciation of botanical subjects.