Читать книгу Solomon - Marilyn Bishop Shaw - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

The Freeman family spent the next few weeks toiling through long, back-breaking days. They had only been on their homestead for a few months and it wasn’t what any of them would call a proper home yet. Lela and a downcast Moses were making trip after trip carrying water from the nearby spring to their water barrel when she reminded her husband, “It’s ours, Moses. I know that trip to the land office wasn’t easy and none of those people wanted us to have any kind of a homestead at all. Oh,” Lela shuddered, “I’ll never forget what a sight you were when you got home. And that was two days after the beating. I almost wished you hadn’t gone.”

Moses shook his head slowly, remembering how humiliating it had been trying to do business with men who obviously didn’t think he deserved to do business. “I was shore stove up some after that. Lela, them men didn’t want to do no business, but they knew the law said they had to do business. Even with a colored man. Days is gettin’ different now, and them that beat me up are gonna just have to see that.”

“You signed up like they said and long as we keep building and working it . . . ” Lela drew in a breath to continue.

“I know what yore gonna say, Miz Freeman, and yore right. We got it so good next to some.” Moses stopped at the edge of the water and leaned against a tree that slanted toward the water’s edge. “Lela, I weren’t the only colored down there. Have to come to Gain’ville from all ’round these parts. They ain’t many land offices and lots of folks come longer ways.”

Lela cooled her feet in the water and looked closely at Moses as he told her the parts he hadn’t told her before. She knew her man; he had never intended to tell her these things. “Were those people beaten, too, Moses?”

“I ’magine but I couldn’t swear it. But, Lela, some of them people didn’t have nothing. They didn’t know nothing neither. Thought they was gettin’ full hundert and sixty acres just to find out they could only get eighty. Them men tried to make ’em pay to sign up, too. An’ it weren’t just colored folks, neither. They was white folks there in same shape as us.”

“What happened to them if they couldn’t pay to register a piece of land?”

“They left. For where I don’t know, but they left.” Moses sat down next to his wife. “We got lucky stars, Lela, comin’ from Hill’s Run. An’ we both know he favored us. Not ever’body left there outfitted as good as us.”

“True enough, Moses, and I’ll never forget that or stop being grateful for it.” Lela popped to her feet and brightened the sunny day. “Just think—eighty whole acres! We treat it proper, and it’ll take care of us. Five years and it’ll be ours clear and all!” Picking up her heavy buckets, she laughed, “Now, Mr. Freeman, we better get to workin’!”

It seemed like everything had to be done at once. The wagon in which they traveled from north Georgia to their Florida homestead was adequate for camping out. Moses and Lela slept in the bed of the wagon and Solomon had a cozy but relatively cool hammock strung between the front and rear axles.

Their place was about six miles southwest of New Troy in Lafayette County, Florida. They were purposely distant from other settlers, hoping they could live peaceably by staying to themselves. Moses laughed about the little hill they chose for their homesite. “Georgia ’least had hills you could tell was hills. Slick as lightnin’ when it were wet and hard packed as bricks when it were dry, that ol’ Georgia clay could do some growin’. Here it hard to see a rise in the land atall.”

It was a dry spot, though, and a fair-sized natural clearing only a short walk to the spring run. That made the choice much easier since they’d have spots to build on without much clearing. Within a half-day’s journey they had found oak hammocks, cypress swamps, spring banks, and river bluffs. There were spots so full of sugar sand, a man could hardly walk through them. Others were springy muck that turned to sucking swamp in a good rain. Every inch was abundant with its own plant and animal life.

The wagon wasn’t much shelter against the erratic climate they found. The weather here could change mood like a lightning bolt. Summer heat with its still, stifling stickiness could turn into a blowing rainstorm. Almost every day through late July and August, there came a thunderstorm. There would be a strong breeze and a muffled rumble of thunder, followed by the summer shower. In just a few minutes, it would taper off and stop, leaves dripping fresh rain. The rain did little more than fill the rain barrel and make the hot air stickier than ever. Solomon observed that they had no need for clocks in summer since the rain always told them when it was three o’clock.

Still sluggish from the heat and humidity, they knew they would soon need real protection from the winter. Without money for materials and hands for heavy labor, a lean-to with blankets covering the opening would see them through a winter or two. It would have to.

There were always wood to be chopped, land to clear, and stumps to dig out. If this was to be a farm, crops had to be planted but that couldn’t be done before the clearing. Moses counted on Sunny and Sudie to pull the plow and drag logs and fat lightered stumps. He fretted that they would only get in a small planting this year, but Lela reassured him, “Moses, you can only do what one man can do. We’ll have a little corn for the mules and maybe a little for meal, too. Sweet taters go a long way and you know Solomon’s gettin’ mighty clever with his traps.”

Lela looked at the little plot right next to the spot they planned to build their shelter. Surveying struggling late-season tomatoes and peas, she added, “My little garden isn’t what I’d like it to be either, but it’s done as well as can be expected against the deer and rabbits taking their share and more.” The diminutive woman stood straight and added, “But, we aren’t starving, and not likely to.” Moses knew he would continue working as hard as he could day after day and time would tell their story.

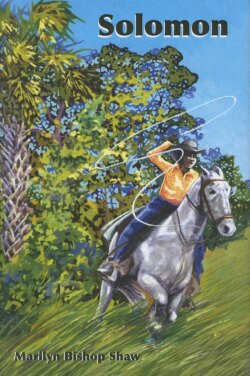

Solomon, a small, wiry eleven-year-old, worked the same long days his parents worked. He did a lot of hand labor—fetching tools, hauling out roots and limbs from newly cleared land, tending the animals. He was also learning to plow the mule. He wasn’t strong enough to manage straight planting rows, but could rough break new land.

Early one May morning, Moses deemed that they had broken enough ground to begin the corn planting, so off they went with Sunny and a little sack of seeds. Moses led the way making long straight rows with the wing plow. Moses’ footprints made a straight path, closer together than a normal stride because of the loose dirt. Into each footprint, Solomon dropped a kernel of corn.

When the two acres were planted, Moses unhitched Sunny from the plow and left him to graze, and he took Sudie with the rope drag into the woods to chop down pine trees. It seemed like they’d never get enough trees cut down to even begin a house. Solomon moved back to the start of the first row of corn and threw dirt from each side on top of the seeds so the corn would grow straight and tall. The hoe he used was a good foot and a half taller than Solomon, but he handled it with a practiced hand. “A body can get mighty thirsty, this heat and hard work,” Solomon said right out loud. He dropped the hoe with four rows to go and trotted toward the stream for a cold drink.

Moses unharnessed Sudie to graze and returned to the camp tired, hands blistered, arms scraped and scratched. Lela had finished putting in her kitchen garden with okra, collard greens, and onions. She was less scraped up, but just as tired as Moses. “Where’s Solomon?” her husband asked.

“I don’t know,” she said with a start. “I thought he was with you.”

“He was till we finished layin’ out the corn.” They were already moving toward the cornfield. “I left ’im to cover the rows and I cut some more trees.”

Everything looked perfectly right, until he discovered the last four rows of corn seed still open to the elements. His hands clinched and his hulking body began to tremble. “Tarnation and the devil! That boy done left a job ag’in.” Lela stepped back and didn’t say a word. She didn’t dare when Moses was in a trembling spell.

Stomping and boiling, Moses looked in all directions without finding their son. His anger boomed through the woods. “Solomon Freeman! You get here, boy. NOW!”

The scrub rattled a disturbance and Moses saw the boy heading back toward the field. “Why, there he is, Lela. There be the master of the house.” The boy’s steps slowed, recognizing the tempest. “Oh, my, wouldn’t I just love to have me some time to waste.” Moses’ voice boomed, “Boy, get here.”

“I’m here, Papa.” Solomon stood as distant as he thought he could get away with.

Opening and clinching his fists time after time and drawing in a deep breath, Moses spoke with dangerous control. “Step in, boy, step in and face it.” Solomon did what he was told. “Me and your Mama workin’ hard as bodies can work to make this place go and you take time to idle away the afternoon doin’ God knows what. Speak for yourself.”

“I’m sorry, Papa,” Solomon began.

“You always sorry. I wants to know where you been.”

“At the stream.” The words tumbled to build an explanation. “I worked steady, Papa, until late and I got powerful thirsty. It don’t take but a minute to run down to the stream and get a drink and cool down a little.”

“Musta been mighty hot, take you hours to cool down.”

Solomon’s, “No, sir,” was met with a grunt. “I got the drink and washed my face some. Then, there was a rabbit and I got it with my sling. We ain’t had meat in a few days and I thought a rabbit would fit pretty good over the fire.”

“That what took you rest of the afternoon?”

“No, sir.” Solomon knew he’d fare better if he faced his father right out. “No, sir, that wasn’t it. I gutted the rabbit and washed up. Then I headed back to finish the corn. But, I noticed a little trail under the brush and built a snare so’s I could catch another rabbit.”

“Humph. Just playing boy’s games when there’s work to be done.”

“No, sir. ’Tweren’t play, Papa,” the words had barely been spoken when his head recoiled from the back of his father’s hand. Lela moaned, but offered no other protest.

“Nothing wrong with the rabbit, boy. But the rest of the work still to git done. You gots to do your part.” Moses’ words were measured carefully, as he came back to reason. “I don’t ’spect a man’s load from you yet. Don’t ask you to do nothing you ain’t able. Now, finish the corn and see to the animals. They be any left, you can have supper.” Lela lingered long enough to be sure that the trickle of blood from his lip was the boy’s worst injury. Then she turned to follow her husband.

While Moses put Sudie in the lot and washed up, Lela put the rabbit Solomon had handed her on a spit over the fire, turning it occasionally as she warmed up the morning’s biscuits and boiled down some poke greens. Moses sat heavily on the log with the water dipper in his hand, and stared into the fire. “Biscuits and poke greens don’t stand up so good on they own. Rabbit go good tonight.”

“Uh-huh.” Lela waited, knowing he would talk soon.

Lela’s patience paid its dividend. “I didn’t hurt him, Lela.”

“No, you didn’t hurt him, not on the outside.” Lela sat and laid a gentle hand on Moses’ arm. “He works hard, Moses, harder than most men. And, he doesn’t act carelessly a purpose.”

“I know it,” Moses said, quietly. “It just sets me afire for him to do his wanderin’ afore he’s finished the work.”

“Is that all it is, Moses?”

“You do know me, don’t you, Lela? I guess it cuts me that he don’t like the farmin’ like I do. Have to say he a mighty help putting a little meat on the table.”

Giving the spit a turn, Lela smiled to herself and turned back to Moses. “When we got freedom, it was for all of us—maybe Solomon more than us. Why don’t you talk with him quiet like about doing his chores and let him know you appreciate his gift for the woods. That would mean the world to him. He looks up to you, you know.”

Moses knew she was right. “I’m tryin’ to get used to it, Lela.” He looked back at the fire. “That’s a fine big rabbit. They be plenty for all three of us to eat our fill.”

“Yes, Moses, there’s plenty for all three.”