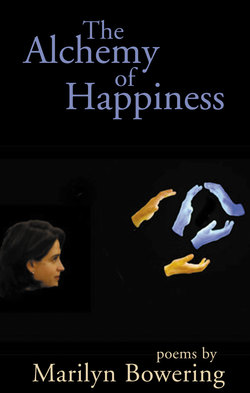

Читать книгу The Alchemy of Happiness - Marilyn Bowering - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеConcerning Self-Examination and the Recollection of God

Self-Examination

You came into this world for one purpose,

and that was to learn

the story of all beings,

but you let the account fade.

You could have asked—they were willing to tell all—

but every hour you neglected dreams

and accumulated regret.

For the whole of your life

you said one thing:

please show me the love in which I reside—

and one day,

in the presence of death,

you saw.

Ah, me.

Shadrach

Sometimes the god

is hanging up laundry

next to a furnace.

He nods, opens the furnace door,

beckons, steps in.

You know who he is,

and his two friends—

sometimes they wash themselves in flames,

sometimes I am washed too,

my skin crisp like gold foil,

sometimes that’s all there is:

just the walking,

and the heart still human, exultant—

for something has been understood

about the flame inside, the flame out,

about thought polished to a

molecule-loosening dagger

that permits all.

Meshack

Sometimes the god watches soap

and water slosh behind glass at a laundromat:

not even he can see who or what

is being cleansed—

he waits, like anyone would,

for an outcome

so he can start over

if he has to, or find some other reason

to link inner and outer,

self and self.

Abednego

No gods are visible,

but people buy groceries,

open and shut car doors beneath

unconscious rain from over the sea.

They are well within the view from my father’s window

where he sits in a chair

to watch a tree yield, light bend, the horizon

flex as darkness tidies itself

into a sharp drumroll.

I mail my letters,

pray he has time to catch that last

glint

of a mast.

Sooner or later I will try

to name that ship.

The Ship

You can choose what form the flame takes

just as I

chose the stone of your white forehead

on which to place my lips,

and that stone, now, entombs me.

I kept from you

my adoration, my passion,

and that you had my heart all along.

A broken cup.

So it is said, so I know

no one enters Heaven

without their father and mother,

some mending,

some rolling away of stones.

North

If the word for a ship means

glacier, even iceberg,

then there are limits to the world:

seven seas slip between

the known world

and its warm shadows,

opposites crack

the planet.

In the Earth’s core—

the fiery furnace.

Inside it, fierce gods

trim their nails,

shape-shift through the hours

it takes to forge a

single silver bangle.

West

Gold straw spikes through

the snow; the horizon

is the next lip of road.

A ball of fire in the sky,

buffalo bones and blue light

in the coulee:

once all the keys are turned

in the lock,

the mountains thin,

the sky tunes itself

to the eye.

All this a gift.

I was not hurt,

just dragging a wing

to lure evil away.

Death

In your heart is a window,

and a furnace in which gods walk, unharmed:

do not accept my word,

follow no one.

The effect of death

is on the heart:

a lamp goes out,

the soul is dismounted.

Don’t listen to me,

don’t run to it.

It sets off and abides.

No vision is necessary,

death is a bridge:

mirror its spaciousness

in the dark wood.

Dark Wood

Hostile to the traveller.

Southeast

Look there: your mother’s hands,

and a latch to reach her;

she understands desire:

how she longed for you.

Longing is a match,

heart with heart.

Look there: a woman and child

draw on the glass I mentioned

(shut or open, broken

or whole)—

snowflake

sun

moon

tree house smoke

fire fire fire

Gold stars on the leaves.

Who?

Someone tells you about serpents

and angels and your heart says:

three friends, a fiery furnace, a stairway,

garden, wood, flight…

Who do you think you are—Dante?

Oh, doubt and mystery. The gods

wash sweaters,

pair socks,

complete the divine between bouts

of carpentry.

The Carpenter

My father says, you cannot tell

the true metal, it is mixed in this world;

he says, let’s make a pact to talk to the dead;

he says, you can’t assess the system you’re in

when you’re in it;

he says, I’m tired of talking to all these spooks.

I crawl out from under the four directions,

to sit with him, on the arm of his recliner,

at a window that looks over a threading willow

to the sea;

we glimpse sails,

and my mother, in the square below,

swishing her skirts against her stockings.

Skirts

You pull my sweater

over my head,

unbutton my kilt,

slip off the pin.

Pajama top,

then bottom,

teeth brushed,

and prayers.

You sit on the bed

and I pleat your skirt

with my fingers;

your kisses pattern my face

like a constellation.

I turn my face toward time:

you step backward, out-of-bounds.

My father and I peer through the fog

that undoes you, feet to eyes,

strands of hair, maybe a ring:

he looks at me, finds you there

as I ready him

trousers, shirt, socks, underwear,

pajama top and bottom

for bed.

Good night

Good night

Here it is.

Once

My friend tells me her dream and I listen fully.

About her son and daughter picking flowers.

They look like little marmots—first, the flowers

and then the children. It is a dream of marmots.

—P. K. Page, “Marmots,” Collected Poems, Volume II

Once, long ago the trees were frozen,

dull winter lowered, there were no flowers or choirs; my mother

still lived—yet the weight of grief, like a sack dully

hoarded, an armful of sad thought and mind

boarded over my eyes. I was an animal

kept warm, but why? Then light bleached the bed,

I sat up from my coffin—

My friend tells me her dream and I listen fully.

Ten dark-robed men stood nearby:

their presence surprised, like the earth mined,

or mountains gullied by time,

ten times the sharp incline and decline of the road.

One helped me step out,

and I stood, in my nightdress, the cold like a shower,

and the coffin folded like a suitcase on a dusty plain;

then the men left for the glacier points, perhaps to cave

or star or even higher.

They’d left her, not with food or water, but a memory—

about her son and daughter picking flowers.

I stood in a bowl of sand with seeds scattered among stones,

mountains on the far rim;

my hands searched the grains,

but change brought tears—and so the watered seeds awakened

until the grey alluvia bloomed,

grass hid the prairie in wind.

I gathered the hum of shortened shadows,

the petal’s face, the turn of hours,

the bees’ rhyme from asphodel to zinnia.

I counted fern-traced stones, sought

the touch of green, its smell…

Sometimes I spied the spill of contents

from that abandoned coffin, left to rot: stained plate and cup,

a faded garment—

then forgot as small animals, born to delight, stirred and crept.

They look like little marmots—first, the flowers

and then the children. It is a dream of marmots.

Then I crept from that rich garden

and stood at the mountain limit, my eyes ached at the sky

and opened to a glimpse of heaven,