Читать книгу Edward James Lennox - Marilyn M. Litvak - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

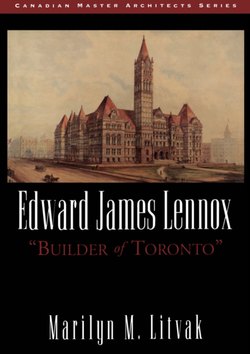

Edward James Lennox’s architecture is still a part of Toronto’s daily life, yet few people recognize the name of the man who was once called “the builder of Toronto.” Lennox was responsible for such key monuments as Old City Hall, the Bank of Toronto on Yonge Street, Casa Loma, and St. Paul’s Anglican Church on Bloor Street East. During the four decades between 1876 and 1917 his output was prodigious. Some of his work has been highlighted in general texts, and articles have been written over the years in praise of Lennox and his architecture, but this is the first time, in the more than sixty years since his death, that a book has been devoted exclusively to his work.

My chief concern has been to convey a sense of Lennox’s importance in Toronto’s architectural history, and to show how his buildings represent his interpretation of contemporary architectural trends.

The task of assembling the photographs, drawings, perspectives, and other records of Lennox’s work was an enormous one. Many buildings known to have been built by Lennox had not been documented. In addition, some information about Lennox and his buildings contained in books, articles, and repositories (building inventories, for instance) proved to be incorrect. For example, various birth dates are given for Lennox: 1854, 1855, and 1856 all appear in different books and articles. However, on the evidence of the chronology of his architectural training, it appears that Lennox’s gravestone in St. James’ Cemetery on Parliament Street gives the correct year – 1854.

The documents are also at variance in their accounts of Lennox’s early practice. For decades his partner was identified as McGaw, sometimes McCaw, with no first name or initials, and their partnership was noted as having dissolved in 1882. It was not until the 1980s that the full and correct name was established: Lennox’s architectural partner was William Frederick McCaw1 and it is clear from the author’s findings that Lennox set out on his own in 1881. Additionally, buildings have been attributed to Lennox which simply are not his — Massey Hall is a good example. It was not designed by Lennox; indeed, it was not even supervised by him. However, once in print, an error in fact becomes a “fact” in error and develops a life of its own. In many ways this project was motivated by the desire to set the record straight, although I am sure I too have been guilty of accepting information that will eventually be proved incorrect.

A search of textual materials, photographs, and drawings related to Lennox and his work was undertaken at such institutions as the Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library, Toronto Historical Board, Toronto City Hall Archives, Ontario Hydro Archives, Federal Department of the Environment (Canadian Historic Buildings Inventory), National Archives of Canada, Ontario Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Recreation, the Niagara Parks Commission, and the Archives of Ontario. I also interviewed a number of Lennox’s descendants.

One of Toronto’s enthusiastic architectural conservationists, Kent Rawson, generously gave me access to his research concerning late nineteenth-century advertisements in Toronto newspapers, specifically, lists of architectural calls for tender. This was most helpful in verifying Lennox’s responsibility for particular buildings and in assigning dates to them, especially when dealing with the early part of Lennox’s career.

Early Toronto city records were searched, and on-site investigation of extant buildings was undertaken. The buildings (including the interior of Lennox’s own home) were photographed. Photographs of destroyed buildings have been reproduced from material such as books, periodicals, slides, and negatives held by various public and private institutions. More than one hundred photographs of Lennox’s buildings were amassed.

Most of the buildings I could verify as Lennox’s works are included in the text and are discussed chronologically; his additions and/or renovations to buildings, unless of major importance to Toronto or indicative of a change in stylistic orientation, are not discussed. Dates assigned to buildings were based on Lennox’s architectural drawings, building permits, calls for tender, listings in city directories, letters, transcripts, and architectural specifications. If no such evidence was available, dates assigned by other writers were accepted and they have been so credited. In 1905 Lennox himself published a promotional portfolio in which many of his buildings are illustrated. As a record of his work it is both helpful and problematic in that the illustrations bear only incomplete addresses and no dates. Lennox left no treatises on architectural theories, no papers outlining his career, no personal papers. He devoted his time to his career, and the writing he did was specific to business dealings, with the exception of a short article published for the purpose of raising funds for the Toronto General Hospital (see Appendix A). When he first started practising architecture in 1876, Toronto’s population was a little more than 70,000. By the time he had completed the building of his home, Lenwil, in 1915, Toronto, with a population approaching half a million, had become a significant metropolis. During those forty years building technologies, systems of transportation, and the means of generating power changed, but the changes had very little effect on Lennox’s architectural vision.

To the end of his life, Lennox was a resolute individualist. While he was not a pioneer of modern design, his traditionalist structures were nonetheless highly original. He designed with an artist’s eye and a sense of theatre; his talent as an architect rested in the power of his imagination and the strength of his artistic will – qualities that ultimately allowed him to put his unique stamp on all his work and set his buildings apart from others.