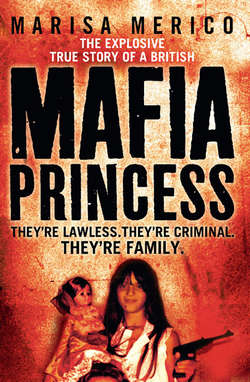

Читать книгу Mafia Princess - Marisa Merico - Страница 10

CHAPTER FOUR ROOM SERVICE

Оглавление‘We seek him here, we seek him there…

Is he in Heaven? – Is he in Hell?

That demmed, elusive Pimpernel.’

BARONESS EMMUSKA ORCZY,

THE SCARLET PIMPERNEL, 1905

Dad was a captain of the new industries, a crime lord, and was acting and living like one. He was turning into a proper Godfather, with scores of soldiers under his command. He seemed to be everywhere but nowhere. He was always wanted by the police for something, even if it was just some petty crime. He was never in one place for long – he scowled out of many passport photographs. The family knew him as ‘Gypsy’ because he criss-crossed the borders of Europe and into Turkey and North Africa.

His power base was Milan. Companies, bars and restaurants were on the payroll, as well as, most importantly, the authorities. This was Nan’s speciality, her business version of tender loving care – bullshit and cash, and lots of both. In pecking order she tied up the lawyers who brought in the magistrates who knew the right judges to approach and fix. She flicked through the corruption process like a pack of cards.

And Dad was just as quickly shuffling his affections. It was rare that he had Italian girlfriends. They arrived on his arm from all over the planet. Mum made sure she had good relationships with his girlfriends now, for she wanted me to stay close to him and she wanted to be comfortable with the girls if I was going to spend any time with them. It wasn’t so difficult for Mum because she had never really loved Dad anyway. She just let go. She was never real friends with him; they tolerated each other because of me.

I got on with most of his girls. Melanie, whose father was a bigwig in the RAF, even took a comb to my nits, which is beyond the call of girlfriend duty. I stayed with her and Dad a few times. I loved the sleepovers and being close to my dad. Dad being there was the most important part of the visits. There was a subliminal feeling I could not experience with any other person. That father and daughter connection. It was different and exciting to be with him. Dad was always very affectionate. He’d mess around with me, we’d have fun. All his girls made a fuss of me, and I liked that.

There were lots of them but Effie the Paraguayan – Miss Paraguay – was special. She looked like a proper Inca woman and behaved almost like a man. She had one of those Aztec top haircuts, and she sat there at my Nan’s smoking a cigar! The family all thought this was great.

Dad lived well. He moved into a luxurious apartment in Milano 2, a residential set-up in Segrate, a new town built by one of Silvio Berlusconi’s companies. It was traffic-free, with bridges and walkways, a gym and a lake in the grounds. It was very upmarket and far removed from the lifestyle Mum and I had. But if Mum ever said anything about this, he retorted, ‘My mother’s looking after you, isn’t she?’

Yet Dad didn’t always get it all his way. He was seriously involved with a stunning French girl but she took a fancy to his sister, my Auntie Mariella. They used to come to my mum’s to be together, to get it on. I came home from school one day to find them in the back of our blue Mini with the white roof. ‘What are they doing?’ I wondered. ‘Why is my dad’s girlfriend in there with my aunt?’

Much as Mum tried to keep it quiet and help, Dad found out and gave my Auntie Mariella a right kicking up the bum; he broke something on her spine, almost crippling her. He didn’t do anything to his girlfriend. Family weren’t meant to betray you.

I was puzzled about it in a little kid sort of way. I couldn’t understand why everyone was upset. Mum told me not to say anything about seeing them together. She probably thought ‘Up yours!’ to my dad. I hope so. No one else would have dared do that.

Dad was doing whatever he wanted, whatever he felt like, but he was too much of a showman and Nan’s payoffs couldn’t guarantee one hundred per cent protection. In 1974 there was a sudden clean-out at City Hall and the appointment of a new police chief with his own set of magistrates. It takes a little time for corruption to seep through the system so, against the odds, a warrant was issued charging Emilio Di Giovine with handling stolen goods. The hunt, the game, was on.

Nan’s apartment is in a courtyard block of about twenty homes. It’s quite a walk from corner to corner. When the police came for my dad one day he thought he was being clever and stole quickly over to the opposite corner from Nan’s. He walked straight into the cops.

They had no photograph of their suspect. They stopped him. Looked at him. Then asked: ‘Do you know who Emilio Di Giovine is?’

‘Oh yes, I’ve heard of him.’

‘What have you heard?’

‘He’s a right one, him.’

‘Do you know if he’s in the area?’

‘I think I saw him about twenty minutes ago.’

‘Do you know where he is?’

Dad could see police trooping into Nan’s. He pointed across the street: ‘He went that way, I think.’

‘Right, thank you.’

Dad had the girlfriend of the moment stashed around a corner. He grabbed her, jumped on a tram and was off. That was his style of stunt. He wouldn’t panic and start running. He would – and could – think on his feet. He would face them up, take the mickey. He loved it.

The newspapers compared him to gentleman thief Arsène Lupin, a fictional and glamorous French criminal who’d been turned into a cartoon character when I was growing up. The people he gets the better of, with lots of style and colourful flair, are always nastier than Lupin. He’s a Robin Hood-style criminal, like Raffles or ‘The Saint’. Lupin! It all added to the cult revolving around Dad.

Still the press kept searching for new descriptions of him. After his next exploit he was compared in the same sentence to Lupin and Rocambole, another popular fictional antihero. Rocambolesque is the tag given to any kind of fantastic adventure. And Dad had many Rocambolesque moments.

The flamboyant publicity just brought more pressure on the cops to get Dad off the streets. Finally, in the summer of 1974, when he was twenty-five years old, they got him into Central Court on robbery charges. He was sentenced to a year in San Vittore prison, Milan’s number one jail, which is renowned for its security.

Dad had as much regard for that security as he had for the law. He was Mafiosi. He’d been inside for only five weeks when his brother visited him. Francesco is five years younger than Dad but looks like his twin. Dad was fed up with being caged.

He and Uncle Francesco talked for a time and then Dad asked him to change sides at the visiting table, to come over and sit in the inmate’s chair for a moment. And wait. In an instant Dad walked over to and out through the visitors’ exit. The next thing Uncle Francesco was being taken into the slammer, to Dad’s cell.

He pleaded: ‘What’s going on? I’m Francesco Di Giovine, not Emilio Di Giovine!’

Finally, the guards clicked. The brothers had swapped.

‘I didn’t know what he was doing. He was so depressed. One minute he was there, the next minute he was telling me to switch seats. And then he was gone.’ That was Uncle Francesco’s bumbled explanation of Dad’s jailbreak, his stroll out of San Vittore, making him able to celebrate being a free man. At least a free man-on-the-run. Typical Dad.

The prison thought it was a set-up but the only person set up was Uncle Francesco. His story was dismissed and he was kept in jail for three months for aiding a jailbreak.

When Nan heard what had happened she exclaimed: ‘Oh, that bloody son of mine.’ No one knew whether it was praise or criticism.

For the front pages it was: ‘Rocambole a San Vittore.’

As they were writing the headlines, Dad was on a train out of the city. He went south, staying with friends, and then from Rome he made some phone calls. One was to Melanie Taylor, who had returned to England when her Continental dance tour was over.

‘My sweetheart! My love! I can’t live without you! I’m flying over to see you. I must be with you.’

He laid it on with a trowel. It was the perfect escape route, a ready-made safe haven. Dad moved to Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, to link up with Melanie, and got a job at the Huntingdonshire Hotel where she worked. He’d never worked in a hotel in his life, he’d never worked legitimately, but he swiftly moved up the ranks and was appointed assistant manager in charge of a huge staff.

One evening in the bar he got into conversation with Giuseppe Salerno, who was also from Milan. Understandably, they got on well and had much to talk about. Salerno was butler to the Earl of Dartmouth, who was staying with friends in the area. Over the hotel’s fine wine Dad and he became great mates. Salerno would drop in to the hotel when he could, or Dad and Melanie would visit him in London at the quiet and elegant Westbury Hotel in Clifford Street, near the Earl’s Mayfair home. This was the house Giuseppe Salerno ran, and his duties included the security of the silverware storeroom. He had the key to lock it. And unlock it.

Which is what he did on a rainy November evening when the Earl was at a charity dinner.

Dad turned up, they bundled out the silver jewellery, plates and cutlery valued at £30,000. Dad drove off back to Huntingdon leaving his new friend Giuseppe tied up and gagged in the entrance hall. It looked like a perfect robbery.

It was for Dad. Not for anyone else. When the Earl returned from his evening, he found his manservant apparently assaulted and robbed, his family silver out the door. Thieves! Robbery!

Melanie helped Dad hide the silver, wrapped in blankets, in a cellar at the hotel. It would be sold when the heat died down. But Giuseppe wasn’t born to crime. He wasn’t injured, there was no sign of forced entry. To the police it looked as though the butler did it.

Giuseppe tripped himself up again and again during his police interviews. After yet another contradiction, he cracked. He pointed the finger at his fellow Italian and the hiding place of the silver. When the police reached the hotel they confronted Melanie. She wouldn’t say where the silver was and it took them three hours to find it. They never found Dad. He was on the run again. When the Cambridge police ran the name Emilio Di Giovine past Interpol and the carabinieri they got an impressive criminal CV in return.

Yet by the time the case reached the Old Bailey in London on 11 August 1975, their man was long, long gone. But his lover was there. Melanie Taylor admitted ‘dishonestly assisting in the removal or retention’ of the stolen silver.

Judge Gwyn Morris seemed to regard her involvement as some sort of crime of passion. And, because she was acting out of ‘love and loyalty’, he gave her a twelve-month conditional discharge. She spoke outside the court to those bewildered by what had happened to this attractive, sensibly dressed blonde from Middle England.

‘I could not give Emilio away. He told me he was a racing driver. I thought I loved him. I had even got things together for my bottom drawer for our wedding. I was duped. I can’t believe it. I’ll never fall for a Latin lover’s charm again. I don’t want to see him any more.’

She hasn’t. By the time Melanie went back to live with her forgiving parents in suburbia, Dad was enlarging a business in which the value of the silver swag would be petty cash. And he was taking much more risk. Melanie won a stay-out-of-jail card. Dad was setting up drug connections throughout Europe and paying the way with other enterprises.

He was involved with his brother Antonio in supplying stolen cars to Kuwait. Members of their organisation would steal the cars in Spain and then ship them over. Officials at the port of entry in Kuwait were fixed and the cars, all expensive, powerful machines – most stolen to order – would literally sail in.

Unexpectedly, there was a payoff breakdown when a ship full of fifty cars was being taken in. There were problems with the paperwork and a Kuwaiti customs officer was arrested. The Spanish police went to town and finally implicated Dad and my uncle. They were locked away in La Modelo Prison in Barcelona in October 1976. Dad wasn’t going to hang around.

He charmed himself a job in the prison hospital so he could see it how it worked – the hours, the people, guards and regulations – and how he could play it to his advantage, snitch his freedom. He’d made friends with an extravagantly connected Italian inmate, a Mafiosi, and got contacts for a gypsy who could help him in Barcelona if – or, in Dad’s case, when – he got out. For weeks he handed out food, helped with the beds and generally made himself useful as he kept his eyes and ears on the system. He found out that if the prison doctor couldn’t figure out what was wrong with an inmate he was shipped off to specialists at Santa Cru Hospital. With an armed guard. Three officers would escort the handcuffed prisoner, wearing regular street clothes so as not to upset regular patients, on the way for treatment and also guard him at the civil hospital.

Dad got very ill. A mystery ailment. The prison medics couldn’t fathom what was wrong. Off he went to hospital in Barcelona. One officer stayed with the car and the other two lads escorted him into the examination room. While they were waiting for a doctor, one of the cops went out for a cigarette. Still handcuffed, Dad grabbed the other guard and quickly locked him in the toilet. Then he was off. He casually walked down the hospital corridor and out of a side entrance and into the Barcelona bustle. There were people everywhere in the middle of a hot afternoon, 7 July 1977. The seventh day of the seventh month, ’77, four of a kind, 7777, a winning trick. He says he felt like Houdini.

And Dad’s luck held, for as the bulls began running in Pamplona that day, he took a long route to Milan. All he had on him was one of the tiny keys you got on cans of corned beef. Dad employed that for all sorts – Fray Bentos robberies, if you like. He’d open every possible lock with those keys, and his speciality was cars. With these tricky little things he’d get a car unlocked quicker than most people could open the can.

Within a few minutes he’d jumped in a taxi and ordered it to drive to the Plaça de Catalunya, which is the busiest square in the city. He had no cash and was hiding his handcuffs so he asked the cab driver to wait while he made a phone call. He ducked into the subway and came out on the other side of the plaza, from where he could see the taxi waiting. He also saw lots of police movement. He went into a toilet and picked the lock on the cuffs. It took a moment. In the street he brazenly stopped a young woman and asked if she’d help him, let him sleep at her house, but she wasn’t having any of that. Imagine! He thought his smile would be enough.

He persuaded a beggar to give him some loose change to call the gypsy contact, but there was no reply. There were a couple of Italian warships in port at Barcelona and he heard a sailor with a Calabrian accent asking for directions. Dad gave him a cock and bull story about being stranded in the city and the lad gave him a load of pesetas. Everywhere he went, he somehow talked people into helping. It was getting dark.

He chanced his luck on the last bus to the outskirts of Barcelona, a trip on which he might or might not be checked. It held again. And good fortune was his once more when he found a minibus at 3 a.m. He clicked it open with his corned beef key and had a couple of hours’ kip.

But even though it was July, the winds were howling, plants were jumping off balconies and the van was rocking. It was early morning when he got to La Rambla pedestrian mall in central Barcelona, but it was packed with tourists who provided people cover. It was before 8 a.m. when he rang the gypsy, who said he’d just got in from his evening and to call back at 1 p.m.

‘Hang on a minute! Look, pal, this is an emergency. I’ve been told you can help me…’

He told Dad to come round, get this bus, do this, do that, take another bus, do that. The front door was opened by a Spanish gypsy who looked like a flamenco dancer. When he and his wife realised who Dad was – his picture was all over the telly – they treated him like a king. They couldn’t do enough for him. This guy did robberies and Dad, the legendary ‘Lupin’, was one of his heroes. The guy showed him what he’d nicked, including some gold bars. While Antonio was stuck in jail and the cops searched land, sea and air for Dad, he put his feet up with them for a week. He rested and plotted.

He always found a way to do everything. There’s nothing that can’t be done by my dad. A fake passport was arranged from Italy, and when it and money arrived he moved on. He took a plane from Barcelona to Madrid and then a train to Malaga and a taxi to Algeciras. From there he took the ferry to Tangiers, where he fell in with a Neapolitan–Moroccan man who entertained him while he waited for three days for the first plane to Rome.

His trail was complex but cold. A bodyguard-driver met him at Fiumicino Airport and they drove back to Milan, which with my family’s efforts was developing into one of the world’s most important drug-trafficking junctions. In tandem, the European ‘Di Giovine Connection’ was operating. It was a family business run from Piazza Prealpi, their estate, their fiefdom. My Auntie Natalina’s husband Luigi Zolla was appointed by Nan as ‘manager’ of the Piazza.

It was recognised, if reluctantly accepted by rival drug organisations, that the Di Giovine family had majority control. Drug suppliers dealt directly and exclusively with the family or there would be trouble. When one of the family’s dealers attempted to set up business for himself, Nan issued only one instruction: ‘Kill him.’

He was murdered within twenty-four hours.

Another dealer didn’t learn that lesson and tried to edge into Di Giovine territory. He died too.

The notoriety increased with the viciousness with which the family’s dominion was protected. Intrusion was not tolerated. Business had to be protected, no matter what.

When Dad’s sister Rita was sixteen years old, she was living at Nan’s with her boyfriend and they started dealing heroin. When thieves brought stolen TVs and other plunder to be fenced they used the money Nan paid them in the kitchen to buy smack off Auntie Rita in the bedroom. It was a clever crime carousel. But there was a big bust-up between Rita and her boyfriend. She was weighing the heroin and cutting it with sugar to make it go further. She didn’t see that as a rip-off. But she didn’t like it that her boyfriend was short-changing their buyers by putting less than the correct weight of heroin mix in the drug packets.

Rita was never Nan’s favourite. She was too needy, too eager to please, and Nan didn’t respect her as a result. She preferred the kids who spoke out and gave the finger to authority. She didn’t always treat Rita terribly well because of this, and when she found out what Rita and her boyfriend were rowing about she went ballistic. She didn’t want anyone in the middle. She wanted total control. After that when the druggies brought stolen goods she paid them in heroin, cutting out her own daughter.

Like a medieval warlord, Nan had an official taster-tester. Only in his teens, Mimmino, who lived out back in a lean-to, wasn’t employed to check the family food for poison but the strength of the heroin. His reaction to his fix would dictate whether the batch could be cut for more profit. A risky business, and he eventually died from an overdose.

There was so much heroin being packed, unpacked, cut and doctored at Nan’s that a couple of neighbours, women who allowed her incoming calls on their untapped phones, were convinced their dogs were being affected, getting high on the aroma and behaving very oddly. In the mêlée of daily life no one else noticed, just gave a shrug when it was mentioned. The dogs seemed content.

Dad was making more connections with the Turkish gangs who were a developing influence in Milan. They operated easily in the shadow of Italy’s kidnapping epidemic in the years after the profitable snatching of John Paul Getty III. The kidnappers targeted kids from rich families and many of the victims were never seen alive again. In 1976 more than eighty men, women and children were held to ransom. The kidnap and murder of Aldo Moro, the two-time Italian Prime Minister, in 1978 remains an open wound for Italy. But with all the scrutiny and risks and no guaranteed profit, kidnapping wasn’t a business my family wanted to move into. Drugs were the future. Yet there’s always friction, with other organisations wanting to expand in the same line of business. It’s impossible to grow without taking up space that others believe belongs to them. There were plenty of ‘others’.

Dad was mixing with a lot of evil people. One sinister gang, nicknamed Kidnaps Inc, was responsible for grabbing twenty-one hostages, three of whom vanished for ever. A Yugoslav called Francesco Mafoda was one of the leaders. He understood Dad’s contacts and influence and tried to recruit him into the organisation. This guy wasn’t just ruthless and mean; he was borderline psychotic. His unsmiling, pockmarked face was a signal he wasn’t a good bet. Dad said no.

Mafoda didn’t like being turned down but Dad was his own man. And a free one. Nan had paid off a judge from a new bank account in Marbella, to finally get the prison swap charges dismissed. Dad fobbed off Mafoda and concentrated on the drugs business. And keeping business in the family. Along with his brothers and sisters, Dad controlled teams in Milan dealing with the Turkish shipments brought in by road, kilos and kilos of heroin often hidden in giant canisters of cooking lard. Week by week the number of trucks, buses, consignments and millions of dollars involved grew and the heroin distribution crews took on new sales teams to spread the deadly but so lucrative product.

For Dad, it was a wonderful world. And something surprising had happened in his life. He was in love. Adele Rossi was only sixteen years old when Dad started dating her. He adored her. She went everywhere with him. He guarded her, looked after her, loved her. They went around hand in hand. They were always touching each other. Not in a sexual way but as though they were making sure the other one was still there; seeing wasn’t enough. She met Mum and me and we liked her. She was lovely, a joyful personality. And beautiful, with long legs and a cascade of blonde hair. Everyone noticed how happy Dad was. He was even happier when Adele got pregnant. And I was delighted, and nervous, at the prospect of having a sister.

In this absurd world, Mum, estranged and separated from her husband, was also trying to have a romantic life but Dad’s power and personality were an ongoing obstruction. He didn’t want to be with Mum but he didn’t want anyone else to be with her either. It was ridiculous but so common in broken relationships. Dad didn’t love Mum in that way, didn’t want to be with her, but was jealous at the thought that someone else might pay her attention.

Some confused and irate husbands might make idle threats if any other man got close to their wife, estranged or not, but with Dad it would have been action not threats. With him so close by, how could Mum ever find happiness again? What man would want to be with her and play surrogate daddy to his little girl when he knew Dad was around the corner? One guy, Gianni, decided he couldn’t live with the risk of reprisals for getting close to Mum and me, and he broke off their relationship.

Mum did see other people, including one guy who was a friend of the family so they had to keep him all hush-hush from Dad. One night he stayed over at the Mussolini flat with its one big room with one big bed. Mum slept on one side, I slept in the middle, and this guy was on the other side. I was seven years old and slept in pyjamas. I didn’t have any underwear on. I woke up in the middle of the night and this guy’s hand was between my legs, on me. He wasn’t messing. It was just there. Plonked on it. What could have happened if I hadn’t woken up? I was lucky he didn’t do anything more.

I pushed his hand away and cuddled up to Mum. I never told anybody. What if I had mentioned it to Nan or my dad? Well, Mum might not be alive. I’m not kidding when I say that. Dad would have taken me from her, chopped the guy’s hands off and killed him.

I can’t condemn Mum. She only wanted some personal happiness, as did Dad, but both in their own ways. Yet Dad had changed. Breaking his own rules about business and pleasure, for that’s all that women had meant before, he took Adele along to his meetings. One evening, on 2 October 1977, he got a call about a heroin shipment worth around £50,000 to the family; nothing to be concerned about, a simple distribution deal. He arranged to meet the contact man, Vittorio Bosisio, at a local coffee shop to make the arrangements for the next day’s delivery.

Unknown to Dad, Vittorio Bosisio was a dead man walking. He had run up hard against a brutal, no-nonsense Yugoslav called Mimmo Pompeo who carried machine pistols like cowboy six-guns. Bosisio hadn’t paid off on a drug shipment and Pompeo issued an order to take him out. But Vittorio Bosisio, hard-faced and streetwise, was crafty and had kept himself alive for three months. Now he needed money, needed a deal. And someone tipped off the Slav where he’d be that evening at 9 p.m.

No one knew that Dad and Adele would be there too. They and Bosisio ordered three double espressos, water and a biscotti each on the side, and were talking quietly when the first spray of automatic fire riddled the windows. The Slavs were determined Bosisio would die. There were eight gunmen firing from behind a line of parked cars. A thunderous rat-a-tat sounded as bullets howled into the cafe. Vittorio Bosisio took the full blast of the assault and his body was punctured from head to toe.

Adele tried to escape by running out of the front door but she rushed headlong into the guns. She was shot in the head, killed instantly, spilling on to the pavement. She’d just turned seventeen years old and was three months pregnant.

Dad acted instinctively, turning his body and throwing his hands up in front of himself, trying to block the gunfire. A barrage of bullets caught him in the arms and legs. The blood spurted and he collapsed onto the tiled floor in a coma, near death.

When the police teams arrived, they arrested him.